The Gastrointestinal Tract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Oesophagus Lined with Gastric Mucous Membrane by P

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.8.2.87 on 1 June 1953. Downloaded from Thorax (1953), 8, 87. THE OESOPHAGUS LINED WITH GASTRIC MUCOUS MEMBRANE BY P. R. ALLISON AND A. S. JOHNSTONE Leeds (RECEIVED FOR PUBLICATION FEBRUARY 26, 1953) Peptic oesophagitis and peptic ulceration of the likely to find its way into the museum. The result squamous epithelium of the oesophagus are second- has been that pathologists have been describing ary to regurgitation of digestive juices, are most one thing and clinicians another, and they have commonly found in those patients where the com- had the same name. The clarification of this point petence ofthecardia has been lost through herniation has been so important, and the description of a of the stomach into the mediastinum, and have gastric ulcer in the oesophagus so confusing, that been aptly named by Barrett (1950) " reflux oeso- it would seem to be justifiable to refer to the latter phagitis." In the past there has been some dis- as Barrett's ulcer. The use of the eponym does not cussion about gastric heterotopia as a cause of imply agreement with Barrett's description of an peptic ulcer of the oesophagus, but this point was oesophagus lined with gastric mucous membrane as very largely settled when the term reflux oesophagitis " stomach." Such a usage merely replaces one was coined. It describes accurately in two words confusion by another. All would agree that the the pathology and aetiology of a condition which muscular tube extending from the pharynx down- is a common cause of digestive disorder. -

Overview of Gastrointestinal Function

Overview of Gastrointestinal Function George N. DeMartino, Ph.D. Department of Physiology University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Dallas, TX 75390 The gastrointestinal system Functions of the gastrointestinal system • Digestion • Absorption • Secretion • Motility • Immune surveillance and tolerance GI-OP-13 Histology of the GI tract Blood or Lumenal Serosal Side or Mucosal Side Structure of a villus Villus Lamina propria Movement of substances across the epithelial layer Tight junctions X Lumen Blood Apical membrane Basolateral membrane X X transcellular X X paracellular GI-OP-19 Histology of the GI tract Blood or Lumenal Serosal Side or Mucosal Side Motility in the gastrointestinal system Propulsion net movement by peristalsis Mixing for digestion and absorption Separation sphincters Storage decreased pressure GI-OP-42 Intercellular signaling in the gastrointestinal system • Neural • Hormonal • Paracrine GI-OP-10 Neural control of the GI system • Extrinsic nervous system autonomic central nervous system • Intrinsic (enteric) nervous system entirely with the GI system GI-OP-14 The extrinsic nervous system The intrinsic nervous system forms complete functional circuits Sensory neurons Interneurons Motor neurons (excitatory and inhibitory) Parasympathetic nerves regulate functions of the intrinsic nervous system Y Reflex control of gastrointestinal functions Vago-vagal Afferent reflex Salivary Glands Composition of Saliva O Proteins α−amylase lactoferrin lipase RNase lysozyme et al mucus O Electrolyte solution water Na+ , K + - HCO3 -

Structure of the Human Body

STRUCTURE OF THE HUMAN BODY Vertebral Levels 2011 - 2012 Landmarks and internal structures found at various vertebral levels. Vertebral Landmark Internal Significance Level • Bifurcation of common carotid artery. C3 Hyoid bone Superior border of thyroid C4 cartilage • Larynx ends; trachea begins • Pharynx ends; esophagus begins • Inferior thyroid A crosses posterior to carotid sheath. • Middle cervical sympathetic ganglion C6 Cricoid cartilage behind inf. thyroid a. • Inferior laryngeal nerve enters the larynx. • Vertebral a. enters the transverse. Foramen of C 6. • Thoracic duct reaches its greatest height C7 Vertebra prominens • Isthmus of thyroid gland Sternoclavicular joint (it is a • Highest point of apex of lung. T1 finger's breadth below the bismuth of the thyroid gland T1-2 Superior angle of the scapula T2 Jugular notch T3 Base of spine of scapula • Division between superior and inferior mediastinum • Ascending aorta ends T4 Sternal angle (of Louis) • Arch of aorta begins & ends. • Trachea ends; primary bronchi begin • Heart T5-9 Body of sternum T7 Inferior angle of scapula • Inferior vena cava passes through T8 diaphragm T9 Xiphisternal junction • Costal slips of diaphragm T9-L3 Costal margin • Esophagus through diaphragm T10 • Aorta through diaphragm • Thoracic duct through diaphragm T12 • Azygos V. through diaphragm • Pyloris of stomach immediately above and to the right of the midline. • Duodenojejunal flexure to the left of midline and immediately below it Tran pyloric plane: Found at the • Pancreas on a line with it L1 midpoint between the jugular • Origin of Superior Mesenteric artery notch and the pubic symphysis • Hilum of kidneys: left is above and right is below. • Celiac a. -

Subserosal Haematoma of the Ileum

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.35.183.509 on 1 October 1960. Downloaded from SUBSEROSAL HAEMATOMA OF THE ILEUM BY ANTONIO GENTIL MARTINS From the Department of Surgery, Alder Hey Children's Hospital, Liverpool (RECEIVED FCR PUBLICATION DECEMBER 21, 1959) Angiomas of the ileum are rare. Their association communicate with the lumen of the small bowel. with a duplication cyst has not so far been described. Opposite, the mucosa had a small erosion'. The unusual mode of presentation, with intestinal Microscopical examination (Figs. 3, 4 and 5) showed and a palpable mass (subserosal that 'considerable haemorrhage had occurred in the obstruction serous, muscular and mucous coats. The mucosa, haematoma) simulating intussusception, have however, was viable and the maximal zone of damage prompted the report of the present case. was towards the serosa. Numerous large capillaries were present in the coats. The lining of the diverticulum Case Report formed by glandular epithelium suggesting ileal mucosa N.C., a white male infant, born June 18, 1958, was was partly destroyed, but it had a well-formed muscular admitted to hospital on May 18, 1959, when 11 months coat': it was considered to be probably a duplication. old, with a five days' history of being irritable and appar- The main diagnosis was that of haemangioma of the ently suffering from severe colicky abdominal pain for ileum. the previous 24 hours. On the day of admission his bowels had not moved and he vomited several times. He looked pale and ill and a mass could be felt in the copyright. -

The Skin As a Mirror of the Gastrointestinal Tract

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22516/25007440.397 Case report The skin as a mirror of the gastrointestinal tract Martín Alonso Gómez,1* Adán Lúquez,2 Lina María Olmos.3 1 Associate Professor of Gastroenterology in the Abstract Gastroenterology and Endoscopy Unit of the National University Hospital and the National University of We present four cases of digestive bleeding whose skin manifestations guided diagnosis prior to endoscopy. Colombia in Bogotá Colombia These cases demonstrate the importance of a good physical examination of all patients rather than just 2 Internist and Gastroenterologist at the National focusing on laboratory tests. University of Colombia in Bogotá, Colombia 3 Dermatologist at the Military University of Colombia and the Dispensario Medico Gilberto Echeverry Keywords Mejia in Bogotá, Colombia Skin, bleeding, endoscopy, pemphigus. *Correspondence: [email protected]. ......................................... Received: 30/01/18 Accepted: 13/04/18 Despite great technological advances in diagnosis of disea- CASE 1: VULGAR PEMPHIGUS ses, physical examination, particularly an appropriate skin examination, continues to play a leading role in the detec- This 46-year-old female patient suffered an episode of hema- tion of gastrointestinal pathologies. The skin, the largest temesis with expulsion of whitish membranes through her organ of the human body, has an area of 2 m2 and a thick- mouth during hospitalization. Upon physical examination, ness that varies between 0.5 mm (on the eyelids) to 4 mm she was found to have multiple erosions and scaly plaques (on the heel). It weighs approximately 5 kg. (1) Many skin with vesicles that covered the entire body surface. After a manifestations may indicate systemic diseases. -

6 Physiology of the Colon : Motility

#6 Physiology of the colon : motility Objectives : ● Parts of the Colon ● Functions of the Colon ● The physiology of Different Colon Regions ● Secretion in the Colon ● Nutrient Digestion in the Colon ● Absorption in the Colon ● Bacterial Action in the Colon ● Motility in the Colon ● Defecation Reflex Doctors’ notes Extra Important Resources: 435 Boys’ & Girls’ slides | Guyton and Hall 12th & 13th edition Editing file [email protected] 1 ﺗﻛرار ﻣن اﻟﮭﺳﺗوﻟوﺟﻲ واﻷﻧﺎﺗوﻣﻲ The large intestine ● This is the final digestive structure. ● It does not contain villi. ● By the time the digested food (chyme) reaches the large intestine, most of the nutrients have been absorbed. ● The primary role of the large intestine is to convert chyme into feces for excretion. Parts of the colon ● The colon has a length of about 150 cm. ( 1.5 meters) (one-fifth of the whole length of GIT). ● It consists of the ascending & descending colon, transverse colon, sigmoid colon, rectum and anal canal. 3 ● The transit of radiolabeled chyme through 4 the large intestine occurs in 36-48 hrs. 2 They know this how? By inserting radioactive chyme. 1 6 5 ❖ Mucous membrane of the colon ● Lacks villi and has many crypts of lieberkuhn. ● They consists of simple short glands lined by mucous-secreting goblet cells. Main colonic secretion is mucous, as the colon lacks digestive enzymes. ● The outer longitudinal muscle layer is modified to form three longitudinal bands called taenia coli visible on the outer surface.(Taenia coli: Three thickened bands of muscles.) ● Since the muscle bands are shorter than the length of the colon, the colonic wall is sacculated and forms haustra.(Haustra: Sacculation of the colon between the taenia.) Guyton corner : mucus in the large intestine protects the intestinal wall against excoriation, but in addition, it provides an adherent medium for holding fecal matter together. -

Human Anatomy and Physiology

LECTURE NOTES For Nursing Students Human Anatomy and Physiology Nega Assefa Alemaya University Yosief Tsige Jimma University In collaboration with the Ethiopia Public Health Training Initiative, The Carter Center, the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, and the Ethiopia Ministry of Education 2003 Funded under USAID Cooperative Agreement No. 663-A-00-00-0358-00. Produced in collaboration with the Ethiopia Public Health Training Initiative, The Carter Center, the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, and the Ethiopia Ministry of Education. Important Guidelines for Printing and Photocopying Limited permission is granted free of charge to print or photocopy all pages of this publication for educational, not-for-profit use by health care workers, students or faculty. All copies must retain all author credits and copyright notices included in the original document. Under no circumstances is it permissible to sell or distribute on a commercial basis, or to claim authorship of, copies of material reproduced from this publication. ©2003 by Nega Assefa and Yosief Tsige All rights reserved. Except as expressly provided above, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the author or authors. This material is intended for educational use only by practicing health care workers or students and faculty in a health care field. Human Anatomy and Physiology Preface There is a shortage in Ethiopia of teaching / learning material in the area of anatomy and physicalogy for nurses. The Carter Center EPHTI appreciating the problem and promoted the development of this lecture note that could help both the teachers and students. -

Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MRI Findings of Acute Pancreatitis in Ectopic Pancreatic Tissue: Case Report and Review of the Literature

University of Massachusetts Medical School eScholarship@UMMS Radiology Publications and Presentations Radiology 2014-07-28 Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI findings of acute pancreatitis in ectopic pancreatic tissue: case report and review of the literature Senthur Thangasamy University of Massachusetts Medical School Et al. Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Follow this and additional works at: https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/radiology_pubs Part of the Digestive System Diseases Commons, and the Radiology Commons Repository Citation Thangasamy S, Zheng L, Mcintosh LJ, Lee P, Roychowdhury A. (2014). Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI findings of acute pancreatitis in ectopic pancreatic tissue: case report and review of the literature. Radiology Publications and Presentations. https://doi.org/10.6092/1590-8577/2390. Retrieved from https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/radiology_pubs/259 Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This material is brought to you by eScholarship@UMMS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Radiology Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of eScholarship@UMMS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOP. J Pancreas (Online) 2014 July 28; 15(4):407-410 CASE REPORT Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MRI Findings of Acute Pancreatitis in Ectopic Pancreatic Tissue: Case Report and Review of the Literature Senthur J Thangasamy1, Larry Zheng1, Lacey McIntosh1, Paul Lee2, Abhijit Roychowdhury1 1Department of Radiology and 2Pathology, University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, MA, USA ABSTRACT Context Acute pancreatitisCase report in ectopic pancreatic tissue is an uncommon cause of acute abdominal pain and can be difficult to diagnose on imaging. -

Yagenich L.V., Kirillova I.I., Siritsa Ye.A. Latin and Main Principals Of

Yagenich L.V., Kirillova I.I., Siritsa Ye.A. Latin and main principals of anatomical, pharmaceutical and clinical terminology (Student's book) Simferopol, 2017 Contents No. Topics Page 1. UNIT I. Latin language history. Phonetics. Alphabet. Vowels and consonants classification. Diphthongs. Digraphs. Letter combinations. 4-13 Syllable shortness and longitude. Stress rules. 2. UNIT II. Grammatical noun categories, declension characteristics, noun 14-25 dictionary forms, determination of the noun stems, nominative and genitive cases and their significance in terms formation. I-st noun declension. 3. UNIT III. Adjectives and its grammatical categories. Classes of adjectives. Adjective entries in dictionaries. Adjectives of the I-st group. Gender 26-36 endings, stem-determining. 4. UNIT IV. Adjectives of the 2-nd group. Morphological characteristics of two- and multi-word anatomical terms. Syntax of two- and multi-word 37-49 anatomical terms. Nouns of the 2nd declension 5. UNIT V. General characteristic of the nouns of the 3rd declension. Parisyllabic and imparisyllabic nouns. Types of stems of the nouns of the 50-58 3rd declension and their peculiarities. 3rd declension nouns in combination with agreed and non-agreed attributes 6. UNIT VI. Peculiarities of 3rd declension nouns of masculine, feminine and neuter genders. Muscle names referring to their functions. Exceptions to the 59-71 gender rule of 3rd declension nouns for all three genders 7. UNIT VII. 1st, 2nd and 3rd declension nouns in combination with II class adjectives. Present Participle and its declension. Anatomical terms 72-81 consisting of nouns and participles 8. UNIT VIII. Nouns of the 4th and 5th declensions and their combination with 82-89 adjectives 9. -

Anatomy of the Digestive System

The Digestive System Anatomy of the Digestive System We need food for cellular utilization: organs of digestive system form essentially a long !nutrients as building blocks for synthesis continuous tube open at both ends !sugars, etc to break down for energy ! alimentary canal (gastrointestinal tract) most food that we eat cannot be directly used by the mouth!pharynx!esophagus!stomach! body small intestine!large intestine !too large and complex to be absorbed attached to this tube are assorted accessory organs and structures that aid in the digestive processes !chemical composition must be modified to be useable by cells salivary glands teeth digestive system functions to altered the chemical and liver physical composition of food so that it can be gall bladder absorbed and used by the body; ie pancreas mesenteries Functions of Digestive System: The GI tract (digestive system) is located mainly in 1. physical and chemical digestion abdominopelvic cavity 2. absorption surrounded by serous membrane = visceral peritoneum 3. collect & eliminate nonuseable components of food this serous membrane is continuous with parietal peritoneum and extends between digestive organs as mesenteries ! hold organs in place, prevent tangling Human Anatomy & Physiology: Digestive System; Ziser Lecture Notes, 2014.4 1 Human Anatomy & Physiology: Digestive System; Ziser Lecture Notes, 2014.4 2 is suspended from rear of soft palate The wall of the alimentary canal consists of 4 layers: blocks nasal passages when swallowing outer serosa: tongue visceral peritoneum, -

GLOSSARYGLOSSARY Medical Terms Common to Hepatology

GLOSSARYGLOSSARY Medical Terms Common to Hepatology Abdomen (AB-doh-men): The area between the chest and the hips. Contains the stomach, small intestine, large intestine, liver, gallbladder, pancreas and spleen. Absorption (ub-SORP-shun): The way nutrients from food move from the small intestine into the cells in the body. Acetaminophen (uh-seat-uh-MIN-oh-fin): An active ingredient in some over-the-counter fever reducers and pain relievers, including Tylenol. Acute (uh-CUTE): A disorder that has a sudden onset. Alagille Syndrome (al-uh-GEEL sin-drohm): A condition when the liver has less than the normal number of bile ducts. It is associated with other characteristics such as particular facies, abnormal pulmonary artery and abnormal vertebral bodies. Alanine Aminotransferase or ALT (AL-ah-neen uh-meen-oh-TRANZ-fur-ayz): An enzyme produced by hepatocytes, the major cell types in the liver. As cells are damaged, ALT leaks out into the bloodstream. ALT levels above normal may indicate liver damage. Albumin (al-BYEW-min): A protein that is synthesized by the liver and secreted into the blood. Low levels of albumin in the blood may indicate poor liver function. Alimentary Canal (al-uh-MEN-tree kuh-NAL): See Gastrointestinal (GI) Tract. Alkaline Phosphatase (AL-kuh-leen FOSS-fuh-tayz): Proteins or enzymes produced by the liver when bile ducts are blocked. Allergy (AL-ur-jee): A condition in which the body is not able to tolerate or has a reaction to certain foods, animals, plants, or other substances. Amino Acids (uh-MEE-noh ASS-udz): The basic building blocks of proteins. -

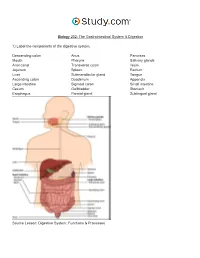

The Gastrointestinal System & Digestion Visual Worksheet

Biology 202: The Gastrointestinal System & Digestion 1) Label the components of the digestive system. Descending colon Anus Pancreas Mouth Pharynx Salivary glands Anal canal Transverse colon Ileum Jejunum Spleen Rectum Liver Submandibular gland Tongue Ascending colon Duodenum Appendix Large intestine Sigmoid colon Small intestine Cecum Gallbladder Stomach Esophagus Parotid gland Sublingual gland Source Lesson: Digestive System: Functions & Processes 2) Label the image below. Serosa Submucous plexus Muscularis externa Submucosa Myenteric plexus Muscular interna Source Lesson: Role of the Enteric Nervous System in Digestion 3) Label the structures of the alimentary canal. Some terms may be used more than once. Vein Mesentery Mucosa Submucosal plexus Epithelium Gland in mucosa Nerve Muscularis Serosa Lymphatic tissue Muscularis mucosae Glands in submucosa Lamina propria Submucosa Duct of gland outside tract Gland in mucosa Lumen Artery Longitudinal muscle Musculararis Areolar connective tissue Circular muscle Myenteric plexus Source Lesson: The Upper Alimentary Canal: Key Structures, Digestive Processes & Food Propulsion 4) Label the image below. Stomach Trachea Lower esophageal sphincter Esophagus Upper esophageal sphincter Source Lesson: The Upper Alimentary Canal: Key Structures, Digestive Processes & Food Propulsion 5) Label the anatomy of the oral cavity. Upper lip Tonsil Inferior labial frenulum Floor of mouth Tongue Superior labial frenulum Lower lip Teeth Retromolar trigone Palatine arch Hard palate Uvula Glossopalatine arch Soft palate Gingiva Source Lesson: The Oral Cavity: Structures & Functions 6) Label the structures of the oral cavity. Some terms may be used more than once. Hard palate Oropharynx Soft palate Pharyngeal tonsil Oral cavity Lingual tonsil Superior lip Teeth Palatine tonsil Tongue Inferior lip Source Lesson: The Oral Cavity: Structures & Functions 7) Label the image below.