Early Years from 1723

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distillery Visitor Centre Information

Distillery Visitor Centre Information We are delighted to welcome back visitors to our Distillery Visitor Experiences across Scotland. Our number one priority is ensuring the safety and wellbeing of our staff, visitors and communities, which is why we’ve made a number of changes to our visitor experiences in line with Scottish Government guidelines. This document will give you the latest updates and information on how we’re making sure that our Distillery Visitor Experiences are a safe place for you. How we’re keeping you and our staff safe 38.2c Temperature checks Pre-bookings only on arrival All experiences must be pre-booked. 37.8c To ensure the safety of our visitors and staff, we will ask all guests to take a temperature check on arrival. 36.8c Reduced Physical Distancing store capacity All staff and visitors will be asked We’ll only allow a limited number of to maintain a physical distance guests in the shop at one time. throughout the distillery. One-way system Hand sanitiser stations This will be clearly marked throughout Installed at the entrance the experience. and in all common areas of the distillery. Extra cleaning We have introduced extra cleaning and Safe check out hygiene routines for your safety. Plastic barriers have been installed at all payment points and contactless payment is strongly advised. Frequently Asked Questions How do I book a tour? Please visit Malts.com to book a tour or email us (details below). Can you share with me your cancellation policy? If you booked online the cancellation policy will be visible on your booking and you will be refunded through the system. -

Das Land Des Whiskys Eine Einführung in Die Fünf Whisky-Regionen Schottlands Schottland

Das Land des Whiskys Eine Einführung in die fünf Whisky-Regionen Schottlands Schottland Highland Speyside Islay Lowland Campbeltown Whisky Die Kunst der Whisky- Keine gleicht der anderen – jede Brennerei wurde in Schottland Brennerei ist stolz auf ihre eigene über Jahrhunderte mit Liebe Geschichte, ihre einzigartige perfektioniert. Alles begann damit, Lage und ihre ganz eigene Art, dass regengetränkte Gerste den Whisky herzustellen, die mit frischem Wasser aus den sich im Laufe der Zeit entwickelt glasklaren schottischen Quellen, und verfeinert hat. Besuchen Sie Flüssen und Bächen in eine eine Brennerei und erfahren Sie trinkbare Spirituose verwandelt mehr über die Umgebung und die wurde. Menschen, die den Geschmack des schottischen Whiskys formen, Bis zum heutigen Tag setzen den Sie genießen. Wenn Sie Brennereien im ganzen Land sich am Ende der Brennerei- die Tradition fort und nutzen seit Führung zurücklehnen und Jahrhunderten pures Quellwasser bei einem Gläschen unseres aus den gleichen Quellen. größten Exportschlagers entspannen, halten Sie in Ihrem Vom Wasser und der Form des Glas gewissermaßen die Essenz Destillierapparats bis zum Holz Schottlands in der Hand. des Fasses, in dem der Whisky reift – es gibt viele Faktoren, Schottland ist weltweit das Land die den schottischen Whisky mit den meisten Brennereien und so besonders machen und lässt sich in fünf verschiedene die einzelnen Brennereien so Whisky-Regionen unterteilen: unterschiedlich. Islay, Speyside, Highland, Lowland und Campbeltown. Erfahren Sie mehr über Schottland: www.visitscotland.com/de Unterkünfte suchen und buchen: www.visitscotland.com/de-de/unterkunft/ 02 03 Islay Unter all den kleinen Inseln vor frischem Quellwasser und der Schottlands Westküste ist Islay von den einheimischen Bauern etwas ganz Besonderes. -

Scotch Whisky Review Tm Tm

SCOTCH WHISKY REVIEW TM TM EDITION 8 AUTMN 1997 A LOAD OF (Ferin)TOSH There is a huge discussion within (and without) the industry about the role of independent bottlings. The matter has recently been in the courts at home and as I write, action is starting in the US. Thankfully, no-one with any influence wants to see the these bottlers removed from the trade but some would have them bound by trade mark considera- tions and with some good argument. In a surprise telephone call, one senior member of the Scotch Whisky Industry asked me if I shared his irritation re- garding a new release of five single malts from Invergordon Distillers. Each a re- gional representitive, three are named after long-gone distilleries; Kincaple, SWAN-UPPING SEASON SUCCESSFUL! Glenluig and Ferintosh—the most his- torical of all Scotch Whisky’s heritage. Speyside’s biggest pots were refurbished during this summer’s silent season. A My caller proposed that where the new swan neck for a wash-still, a new condenser and a still house roof were in- appelation ‘single’ is employed the dis- stalled at Glenfarclas. Stills last about 15-20 years producing about 15 million litres of Glenfarclas in that time. See p8 for a bonzer deal on the 15 & 30yo. tillery of origin should be declared as well as the bottler responsible. As Loch Fyne Whiskies only stocks malts with HOORAY! GLEN GARIOCH: LOWLAND REVIVAL LIKELY the distillery of origin clearly defined our The future of two closed Lowland dis- policy should be clear but I thought it BACK FROM EXTINCTION tilleries looks brighter—thanks to the strange that a major producer with sev- Just in time for its 200th anniversary potential of tourism. -

Lowland the Land of Whisky

The Land of Whisky A visitor guide to one of Scotland’s five whisky regions. Lowland Whisky The practice of distilling whisky No two are the same; each has has been lovingly perfected its own proud heritage, unique throughout Scotland for centuries setting and its own way of doing and began as a way of turning things that has evolved and been rain-soaked barley into a drinkable refined over time. Paying a visit to spirit, using the fresh water a distillery lets you discover more from Scotland’s crystal-clear about the environment and the springs, streams and burns. people who shape the taste of the Scotch whisky you enjoy. So, when To this day, distilleries across the you’re sitting back and relaxing country continue the tradition with a dram of our most famous of using pure spring water from export at the end of your distillery the same sources that have been tour, you’ll be appreciating the used for centuries. essence of Scotland as it swirls in your glass. From the source of the water and the shape of the still to the wood Home to the greatest concentration of the cask used to mature the of distilleries in the world, Scotland spirit, there are many factors that is divided into five distinct make Scotch whisky so whisky regions. These are Islay, wonderfully different and varied Speyside, Highland, Lowland and from distillery to distillery. Campbeltown. Find out more information about whisky, how it’s made, what foods to pair it with and more: www.visitscotland.com/whisky For more information on travelling in Scotland: www.visitscotland.com/travel Search and book accommodation: www.visitscotland.com/accommodation EDEN MILL Lowland DAFTMILL KINGBARNS With miles of rolling farmland and also home to five of the country’s neat woodlands, the Lowlands seven high-volume grain distilleries, CAMERONBRIDGE is one of the most charming and which, although they aren’t open accessible whisky regions in to the public, continue to produce Scotland. -

F-W-Whisky-Bar-Menu-Web-1.Pdf

Scotland, my auld, respected mither! Tho’ whiles ye moistify your leather, Till, whare ye sit on craps o’ heather, Ye tine your dam; Freedom an’ whisky gang thegither! Take aff your dram! WHISKY MENU SCOTLAND’S DISTILLERY REGIONS Highland INVERNESS Speyside ABERDEEN ISLANDS Islay GLASGOW EDINBURGH Campeltown Lowland SPEYSIDE INVERNESS Speyside ABERDEEN GLASGOW EDINBURGH The region gets its name from the River Spey which carves its way through the area, supplying the distilleries with what becomes ‘uisge-beatha’. This is the heartland of whisky and is a popular destination for whisky enthusiasts from all around the world. Many come to devote themselves to the Holy Mother of Malts! Home to over half of the distilleries around Scotland, it is a treat to discover an array of aromas and flavours that will leave you wanting more. Famous for light, fruity characteristics, each distillery has its own unique quirks, creating a very long bucket list of distilleries to sample. SPEYSIDE ABERLOUR DISTILLERY Aberlour translates to Obar Lobhair in Gaelic meaning ‘the mouth of the talkative or noisy stream’, and was founded by James Fleming in 1879, whose family motto is, ‘Let the deed show”. The distillery is supplied by the Rivers Lour and Spey, which is a short distance from Ben Rinnes and is in the heart of Speyside. As a little curiosity, the distillery pours a bottle of Aberlour 12-year-old into the River Spey every year, to mark the start of the salmon fishing season in February. This little ritual is to ‘bless’ the water in hope of a good fishing season for locals. -

Whisky at Garleton Lodge (June 2020)

Scotch Malt Whisky @ Garleton Lodge Each of our rooms is named after a distillery situated in one of the six Scotch whisky regions – Lowland, Highland, Speyside, Campbeltown, Islands and Islay - chosen for its connection with ourselves during our travels around Scotland. In your room you will find a decanter with a small sample of the whisky from the named distillery – please enjoy this with our compliments and come along to the bar to try the others! Meantime, we hope that the below enables you to enjoy your sample dram a little more… Angela & David ABERLOUR [ah-bur-lower] This Speyside distillery was established on the site of a holy well dedicated to St Drostan (who became Archbishop of Canterbury in 960). The well was long used for baptisms but in more recent years dried up. Happily, it began to gush forth again the year the malt won top prize at an International Wine and Spirit Competition! The distillery was rebuilt in 1879, and again in 1898 (following a fire) and extended to four stills in 1973; taking its name from the nearby village. The core range of Aberlour includes 12, 16 and 18 years old matured in either ex-bourbon or ex-sherry casks. Our personal favourite is Aberlour a’bunadh matured in ex-Oloroso casks and bottled at cask strength! Tasting Notes (12 Year Old): The nose offers brown sugar, honey and sherry with a hint of grapefruit citrus. The palate is sweet with buttery caramel, maple syrup and eating apples. Liquorice, peppery oak and mild smoke in the finish. -

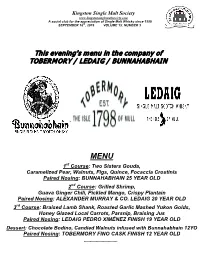

This Evening's Menu in the Company of TOBERMORY / LEDAIG / BUNNAHABHAIN

Kingston Single Malt Society www.kingstonsinglemaltsociety.com A social club for the appreciation of Single Malt Whisky since 1998 SEPTEMBER 16th, 2019 VOLUME 13; NUMBER 3 This evening's menu in the company of TOBERMORY / LEDAIG / BUNNAHABHAIN MENU 1st Course: Two Sisters Gouda, Caramelized Pear, Walnuts, Figs, Quince, Focaccia Crostinis Paired Nosing: BUNNAHABHAIN 25 YEAR OLD 2nd Course: Grilled Shrimp, Guava Ginger Chili, Pickled Mango, Crispy Plantain Paired Nosing: ALEXANDER MURRAY & CO. LEDAIG 20 YEAR OLD 3rd Course: Braised Lamb Shank, Roasted Garlic Mashed Yukon Golds, Honey Glazed Local Carrots, Parsnip, Braising Jus Paired Nosing: LEDAIG PEDRO XIMÉNEZ FINISH 19 YEAR OLD Dessert: Chocolate Bodino, Candied Walnuts infused with Bunnahabhain 12YO Paired Nosing: TOBERMORY FINO CASK FINISH 12 YEAR OLD ---------------------------- COST OF THE MALTS Winners at the June BBQ Mystery Single Malt Bottle brought Perfect Attendance Award Winners by Mike Brisebois Roberto Di Fazio alongside ALEXANDER MURRAY & CO. LEDAIG 20 Ainsley Creighton, Anne Holley-Hime; David YEAR OLD; DISTILLED 1997; BOTTLED 2017 Simourd, Chantaille Buczynski & Mike Patchett LCBO 941068 | 750 mL bottle Price $174.95 Spirits, Scotch 50.0% Alcohol/Vol. LEDAIG PEDRO XIMÉNEZ FINISH 19 YEAR OLD SINGLE MALT VINTAGES 647164 | 750 mL bottle Price $329.00 Spirits, Whisky/Whiskey, Scotch Single Malts 55.7% Alcohol/Vol. TOBERMORY 12 YEAR OLD SINGLE MALT, VINTAGES 37259 | 700 mL bottle, Price: $69.40, Spirits, Whisky, Scotch Whisky 46.3% Alcohol/Vol. TOBERMORY FINO CASK FINISH 12 YEAR OLD MULL SINGLE MALT VINTAGES 647172 | 750 mL bottle Price: $229.00 Spirits, Whisky/Whiskey, Scotch Single Malts 55.1% Alcohol/Vol. ---------------------------- BUNNAHABHAIN 12 YEAR OLD VINTAGES Final Exam Winners (out of 18 points) 250076 | 750mL bottle Price: $87.05 Spirits, Elsabe Falkson (10 of 18) - Bunnahabhain Toiteach A’Dha Scotch Whisky 46.3% Alcohol/Vol. -

STORIES of SCOTLAND Castles, Gardens, Battlefields and Much More!

STORIES OF SCOTLAND Castles, gardens, battlefields and much more! Ideal for groups and FITs on short breaks and touring holidays. As one of the UK’s largest conservation charities, we manage many of Scotland’s favourite heritage attractions, including world-famous gardens, historic battle sites, castles, palaces and stately homes. Many are 4 and 5 star visitor attractions with multi-lingual interpretation, tax free shopping and group-friendly cafes. GLENCOE VISITOR GLENFINNAN INVEREWE GARDEN CORRIESHALLOCH CULLODEN BRODIE CASTLE FYVIE CASTLE, PITMEDDEN GARDEN CENTRE MONUMENT & ESTATE GORGE BATTLEFIELD GARDEN & ESTATE Unst Unst Yell Yell Thurso Thurso ShetlandShetland N N A99 A99 ARDUAINE GARDEN A836 A836 DRUM CASTLE A9 A9 Fair Isle Fair Isle Lewis Lewis A9 A9 A837 A837 Orkney Orkney St KildaSt Kilda CRARAE GARDEN 41 miles41 west miles west CRATHES CASTLE, of Northof Uist North Uist A832 Ullapool Inverewe UllapoolA832 GARDEN & ESTATE Garden Inverewe Corrieshalloch Gorge Harris Harris PooleweCorrieshalloch Gorge North Hugh MillerA9 ’s A9 North A832 Uist A832 Hugh MillerBirthplace’s Coage CromarBrodiety Castle Uist Birthplace Coage& Museum Fraserburgh A832 Brodie CastleA98 A98 A98 Skye Skye A832 Garve& Museum A98 Benbecula A947 Benbecula TorridonTorridon Boath Doocot NairnBoath Doocot A947 A948 A896 A948 Shieldaig Shieldaig A896 Culloden A96 A96 Island A890 A890 Inverness Culloden Fyvie Castle South UistSouth Uist Island Inverness Balefield Fyvie Castle Strome Castle Huntly Strome Castle Haddo HouseHaddo House HOUSE OF DUN THE HILL HOUSE -

Reduced Rate Certificate 21 Jul 2017

Climate Change Levy: Reduced Rate Certificate 21 Jul 2017 (For the purposes of Paragraph 44 of Schedule 6 to the Finance Act 2000) The Environment Agency certifies that the following facilities in the Spirits sector are to be taken as being covered by a climate change agreement made between the Environment Agency and the Spirits Energy Efficiency Company (SEEC) for the certification period 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2019, except where noted below: This notice may be varied by later notices. Last Updated: 21 Jul 2017 Start Date Of Facility Identifier TU Operator Name Facility Address Certification SEEC/F00002 The Old Bushmills Old Bushmills Distillery, 2 Distillery Road, Bushmills, Distillery Co. Ltd County Antrim, BT57 8HX, Northern Ireland (Companies House NI000601) SEEC/F00003 Chivas Brothers Aberlour Distillery, Aberlour, Aberlour, Banffshire, AB38 Limited 9PJ, Scotland SEEC/F00005 Glen Turner Glen Moray Distillery, Glen Moray Distillery, Bruceland Company Ltd Road, Elgin, IV30 1YE, Scotland SEEC/F00006 Inver house Distillers Speyburn Distillery, Speyburn Distillery, Rothes, Aberlour, AB38 7AG, Scotland SEEC/F00007 The North British North British Distillery, 9 Wheatfield Road, Edinburgh, Distillery Company EH11 2PX, Scotland Limited SEEC/F00008 Ian MacLeod Glengoyne Distillery, Glengoyne Distillery, Dumgoyne, Nr Distillers Ltd Killearn, Stirlingshire, G63 9LB, Scotland (Companies House SC032696) SEEC/F00012 Highland Distillers Ltd Glenrothes Distillery, Glenrothes Distillery, Rothes, Aberlour, Banffshire, AB38 7AA, Scotland SEEC/F00013 -

Scotch Whisky in Depth an Insider’S Journey to the Land of Scotch Whisky

Scotch Whisky In Depth An insider’s journey to the land of Scotch Whisky Explore the beautiful whisky-producing regions of Scotland with celebrated Whisky Ambassador Ronnie Berri Just a sip of Scotch Whisky can evoke an entire sen- After completing an in-depth masterclass at the sory experience: visions of craggy moors and rolling Scotch Whisky School in Edinburgh, you travel to six- hills interrupted only by an endless sky; the smell of teen celebrated distilleries in The Lowlands, The High- peat bogs and handcrafted barrels; a cool, crisp, wind- lands, Speyside, and Islay, guided by acclaimed Scotch swept landscape. Indeed, many people admit to be- Whisky expert Ronnie Berri – an official Whisky Am- ginning a lifelong romance with Scotch from their bassador for Scotland. At each, you receive personal very first taste. But just what exactly sets this prized instruction while nosing, tasting, and enjoying whisky, spirit apart from others and often stirs such passion in discovering how the rich resources of the region lend those who partake? their unique characteristics to the spirit. This exclusive, guided tour to historic distilleries in But this is so much more than just a whisky tour. the four main whisky-producing regions of Scotland Because along the way, you also have the opportunity helps you further attune your senses to the complexi- to experience Scotland's mesmerizing landscape and ties of individual malts and the roles that land, air, explore its breathtaking countryside. You learn its fas- water, and a painstaking distillation process play in cinating history, observe its culture and traditions, creating the unique character found in each sip. -

Insight Department: Whisky Tourism – Facts and Insights

Insight Department: Whisky Tourism – Facts and Insights Topic Paper March 2015 (Updated 2018) 1 2 INSIGHT DEPARTMENT: WHISKY TOURISM – FACTS AND INSIGHTS Welcome The following paper is a brief overview of the Scottish Whisky industry and its importance in regards to Scottish Tourism. This paper has been compiled using a number of secondary sources as well as research conducted by VisitScotland. The Year of Food and Drink Scotland 2015 is a Scottish Government initiative led in partnership by EventScotland, VisitScotland and Scotland Food & Drink. It offers the opportunity to spotlight, celebrate and promote Scotland’s natural larder and in doing so, further develop Scotland’s reputation as a Land of Food and Drink. In addition, the Food & Drink sector is fully acknowledged as a key part of the Tourism Scotland 2020 strategy. Key Statistics • Scotland has 5 distinct whisky regions, Highland, Speyside, Lowland, Islay, and Campbelltown, which all have unique characteristics and flavours that differentiate them. • The whisky industry is recognised as the UK’s largest single food and drink sector, which accounts for 25% of the UK’s food and drink exports, and 80% of Scottish food and drink exports, impacting 200 markets worldwide. • The whisky sector generates £3.3 billion directly to the UK economy, and totals £5 billion when Gross Value Added (GVA) is added to the overall to UK Gross Domestic Product (GDP). • France and USA generate the greatest levels of volume and value in terms of exports of Scotch Whisky. • Emerging markets such as Brazil, India, Mexico, and UAE have achieved overall growth between 2012 and 2013 in terms of both volume and value in exports. -

Whisk(E)Y Book

Whisk(e)y Book EDITION 9.26.21 Tasting Flights In our own journeys through whisk(e)y we’ve found that it is better to ask the right questions than believe we have all the answers. Our flights below represent explorations of a few questions that we’ve often received from guests, or those we’re currently excited about ourselves. Come, explore with us and learn something new! Cheers, The Whisk(e)y Team Jack Rose Barrel Picks $32 What can I only find here at Jack Rose? What does the staff look for in a whisk(e)y? B2144 Stellum Bourbon “Jack Rose” Single Barrel ST | x YR, 114.02° 9 B2043 Wilderness Trail High Rye Bourbon “Jack Rose 2021” Single Barrel | 4 YR 8 MO, 114° 8 W295 Penderyn Single Malt “Jack Rose - Apples to Armagnac” F-Oloroso CS | 9 YR, 59.98 abv 15 Ryes to Write Home About $28 What sorts of flavors do we see in rye whiskey? How is it different from Bourbon? R551 New Riff Single Barrel Rye #4524 UCF | 4 YR, 105.5° 10 R513 Laws San Luis Valley Rye BIB | 6 YR, 100° 9 R492 Peerless Rye Small Batch KST UCF | x YR, 110.7° 9 The Diversity of Japan $36 What does Japanese whisky taste like? Are there generalizations that we can make about the category? W271 Takamine Whiskey (Koji Fermented) | B. 2020, 8 YR, 40 abv 12 W301 Fuji Single Grain Whiskey | x YR, 46 abv 13 W177 Ohishi Whisky Sherry Cask | 8 YR, 42.3 abv 11 Shades of Peat $34 What does it mean for a whisky to be peated? Do they all taste the same? S1271 Ardmore John Milroy Refill Hogshead CS UCF | 8YR , 54.8 abv 10 IS556 Kilchoman Sanaig (Bourbon & Sherry Casks) UCF | x YR, 46 abv 9 IS968 Bunnahabhain SV “Jack Rose” Staoisha Heavily Peated Single Cask | 6 YR, 59.2 abv 15 Table of Contents SINGLE MALT SCOTCH WHISKY BY DISTILLERY..........................................................................................................3-17 Scotch Malt Whisky Society .............................................................................