Article RIP622 Part1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Old Norse Mythology — Comparative Perspectives Old Norse Mythology— Comparative Perspectives

Publications of the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature No. 3 OLd NOrse MythOLOgy — COMParative PersPeCtives OLd NOrse MythOLOgy— COMParative PersPeCtives edited by Pernille hermann, stephen a. Mitchell, and Jens Peter schjødt with amber J. rose Published by THE MILMAN PARRY COLLECTION OF ORAL LITERATURE Harvard University Distributed by HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England 2017 Old Norse Mythology—Comparative Perspectives Published by The Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, Harvard University Distributed by Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England Copyright © 2017 The Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature All rights reserved The Ilex Foundation (ilexfoundation.org) and the Center for Hellenic Studies (chs.harvard.edu) provided generous fnancial and production support for the publication of this book. Editorial Team of the Milman Parry Collection Managing Editors: Stephen Mitchell and Gregory Nagy Executive Editors: Casey Dué and David Elmer Production Team of the Center for Hellenic Studies Production Manager for Publications: Jill Curry Robbins Web Producer: Noel Spencer Cover Design: Joni Godlove Production: Kristin Murphy Romano Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Hermann, Pernille, editor. Title: Old Norse mythology--comparative perspectives / edited by Pernille Hermann, Stephen A. Mitchell, Jens Peter Schjødt, with Amber J. Rose. Description: Cambridge, MA : Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, 2017. | Series: Publications of the Milman Parry collection of oral literature ; no. 3 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifers: LCCN 2017030125 | ISBN 9780674975699 (alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Mythology, Norse. | Scandinavia--Religion--History. Classifcation: LCC BL860 .O55 2017 | DDC 293/.13--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017030125 Table of Contents Series Foreword ................................................... -

Stevenson Memorial Tournament 2018 Edited by Jordan

Stevenson Memorial Tournament 2018 Edited by Jordan Brownstein, Ewan MacAulay, Kai Smith, and Anderson Wang Written by Olivia Lamberti, Young Fenimore Lee, Govind Prabhakar, JinAh Kim, Deepak Moparthi, Arjun Nageswaran, Ashwin Ramaswami, Charles Hang, Jacob O’Rourke, Ali Saeed, Melanie Wang, and Shamsheer Rana With many thanks to Brad Fischer, Ophir Lifshitz, Eric Mukherjee, and various playtesters Packet 2 Tossups: 1. An algorithm devised by this person uses Need, Allocated, and Available arrays to keep the system in a safe state when allocating resources. This scientist, Hoare, and Dahl authored the book Structured Programming, which promotes a paradigm that this man also discussed in a handwritten manuscript that popularized the phrase “considered harmful.” Like Prim’s algorithm, an algorithm by this person can achieve the optimal runtime of big-O of E plus V-log-V using a (*) Fibonacci heap. This man expanded on Dekker’s algorithm to propose a solution to the mutual exclusion problem using semaphores. The A-star algorithm uses heuristics to improve on an algorithm named for this person, which can fail with negative-weight edges. For 10 points, what computer scientist’s namesake algorithm is used to find the shortest path in a graph? ANSWER: Edsger Wybe Dijkstra [“DIKE-struh”] <DM Computer Science> 2. A design from this city consists of a window with a main panel and two narrow double-hung windows on both sides. The DeWitt-Chestnut Building in this city introduced the framed tube structure created by an architect best known for working in this city. Though not in Connecticut, a pair of apartment buildings in this city have façades with grids of steel and glass curtain walls and are called the “Glass House” buildings. -

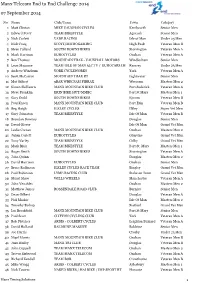

Manx Telecom End to End Challenge 2014 07 September 2014

Manx Telecom End to End Challenge 2014 07 September 2014 No Name Club/Team Town Category 1 Matt Clinton MIKE VAUGHAN CYCLES Kenilworth Senior Men 2 Edward Perry TEAM BIKESTYLE Agneash Senior Men 3 Nick Corlett VADE RACING Isle of Man Under 23 Men 4 Nick Craig SCOTT/MICROGAMING High Peak Veteran Men B 5 Steve Calland SOUTH DOWNS BIKES Storrington Veteran Men A 6 Mark Harrison EUROCYCLES Onchan Veteran Men A 7 Ben Thomas MOUNTAIN TRAX - VAUXHALL MOTORS Windlesham Senior Men 8 Leon Mazzone TEAMCYCLING ISLE TEAM OF MAN 3LC.TV / EUROCARS.IM Ramsey Under 23 Men 9 Andrew Windrum YORK CYCLEWORKS York Veteran Men A 10 Scott McCarron MOUNTAIN TRAX RT Lightwater Senior Men 11 Mat Gilbert 9BAR WRECSAM FIBRAX Wrecsam Masters Men 2 12 Simon Skillicorn MANX MOUNTAIN BIKE CLUB Port Soderick Veteran Men A 13 Steve Franklin ERIN BIKE HUT/MMBC Port St Mary Masters Men 1 14 Gary Dodd SOUTH DOWNS BIKES Epsom Veteran Men B 15 Paul Kneen MANX MOUNTAIN BIKE CLUB Port Erin Veteran Men B 16 Reg Haigh ILKLEY CYCLES Ilkley Super Vet Men 17 Gary Johnston TEAM BIKESTYLE Isle Of Man Veteran Men B 18 Brendan Downey Douglas Senior Men 19 David Glover Isle Of Man Grand Vet Men 20 Leslie Corran MANX MOUNTAIN BIKE CLUB Onchan Masters Men 2 21 Julian Corlett EUROCYCLES Glenvine Grand Vet Men 22 Tony Varley TEAM BIKESTYLE Colby Grand Vet Men 23 Mark Blair TEAM BIKESTYLE Port St. Mary Masters Men 1 24 Roger Smith SOUTH DOWNS BIKES Storrington Veteran Men A 25 John Quinn Douglas Masters Men 2 26 David Harrison EUROCYCLES Onchan Senior Men 27 Bruce Rollinson ILKLEY CYCLES RACE -

GD No 2017/0037

GD No: 2017/0037 isle of Man. Government Reiltys ElIan Vannin The Council of Ministers Annual Report Isle of Man Government Preservation of War Memorials Committee .Duty 2017 The Isle of Man Government Preservation of War Piemorials Committee Foreword by the Hon Howard Quayle MHK, Chief Minister To: The Hon Stephen Rodan MLC, President of Tynwald and the Honourable Council and Keys in Tynwald assembled. In November 2007 Tynwald resolved that the Council of Ministers consider the establishment of a suitable body for the preservation of War Memorials in the Isle of Man. Subsequently in October 2008, following a report by a Working Group established by Council of Ministers to consider the matter, Tynwald gave approval to the formation of the Isle of Man Government Preservation of War Memorials Committee. I am pleased to lay the Annual Report before Tynwald from the Chair of the Committee. I would like to formally thank the members of the Committee for their interest and dedication shown in the preservation of Manx War Memorials and to especially acknowledge the outstanding voluntary contribution made by all the membership. Hon Howard Quayle MHK Chief Minister 2 Annual Report We of Man Government Preservation of War Memorials Committee I am very honoured to have been appointed to the role of Chairman of the Committee. This Committee plays a very important role in our community to ensure that all War Memorials on the Isle of Man are protected and preserved in good order for generations to come. The Committee continues to work closely with Manx National Heritage, the Church representatives and the Local Authorities to ensure that all memorials are recorded in the Register of Memorials. -

1 the Legendary Saga of the Volsungs Cecelia Lefurgy Viking Art and Literature October 4, 2007 Professor Tinkler and Professor E

1 The Legendary Saga of the Volsungs Cecelia Lefurgy Viking Art and Literature October 4, 2007 Professor Tinkler and Professor Erussard Stories that are passed down through oral and written traditions are created by societies to give meaning to, and reinforce the beliefs, rules and habits of a particular culture. For Germanic culture, The Saga of the Volsungs reflected the societal traditions of the people, as well as their attention to mythology. In the Saga, Sigurd of the Volsung 2 bloodline becomes a respected and heroic figure through the trials and adventures of his life. While many of his encounters are fantastic, they are also deeply rooted in the values and belief structures of the Germanic people. Tacitus, a Roman, gives his account of the actions and traditions of early Germanic peoples in Germania. His narration remarks upon the importance of the blood line, the roles of women and also the ways in which Germans viewed death. In Snorri Sturluson’s The Prose Edda, a compilation of Norse mythology, Snorri Sturluson touches on these subjects and includes the perception of fate, as well as the role of shape changing. Each of these themes presented in Germania and The Prose Edda aid in the formation of the legendary saga, The Saga of the Volsungs. Lineage is a meaningful part of the Germanic culture. It provides a sense of identity, as it is believed that qualities and characteristics are passed down through generations. In the Volsung bloodline, each member is capable of, and expected to achieve greatness. As Sigmund, Sigurd’s father, lay wounded on the battlefield, his wife asked if she should attend to his injuries so that he may avenge her father. -

“The Symmetrical Battle” Extended: Old Norse Fránn and Other Symmetry in Norse-Germanic Dragon Lore

The Macksey Journal Volume 1 Article 31 2020 “The Symmetrical Battle” Extended: Old Norse Fránn and Other Symmetry in Norse-Germanic Dragon Lore Julian A. Emole University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.mackseyjournal.org/publications Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, German Linguistics Commons, Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Emole, Julian A. (2020) "“The Symmetrical Battle” Extended: Old Norse Fránn and Other Symmetry in Norse-Germanic Dragon Lore," The Macksey Journal: Vol. 1 , Article 31. Available at: https://www.mackseyjournal.org/publications/vol1/iss1/31 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Johns Hopkins University Macksey Journal. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Macksey Journal by an authorized editor of The Johns Hopkins University Macksey Journal. “The Symmetrical Battle” Extended: Old Norse Fránn and Other Symmetry in Norse-Germanic Dragon Lore Cover Page Footnote The title of this work was inspired by Daniel Ogden's book, "Drakōn: Dragon Myth & Serpent Cult in the Greek & Roman Worlds," and specifically his chapter titled 'The Symmetrical Battle'. His work serves as the foundation for the following outline of the Graeco-Roman dragon and was the inspiration for my own work on the Norse-Germanic dragon. This paper is a condensed version of a much longer unpublished work, which itself is the product of three years worth of ongoing research. -

Herjans Dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age

Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age Luke John Murphy Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Félagsvísindasvið Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age Luke John Murphy Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Leiðbeinandi: Terry Gunnell Félags- og mannvísindadeild Félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands 2013 Ritgerð þessi er lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni Trú og er óheimilt að afrita ritgerðina á nokkurn hátt nema með leyfi rétthafa. © Luke John Murphy, 2013 Reykjavík, Ísland 2013 Luke John Murphy MA in Old Nordic Religions: Thesis Kennitala: 090187-2019 Spring 2013 ABSTRACT Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Feminities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age This thesis is a study of the valkyrjur (‘valkyries’) during the late Iron Age, specifically of the various uses to which the myths of these beings were put by the hall-based warrior elite of the society which created and propagated these religious phenomena. It seeks to establish the relationship of the various valkyrja reflexes of the culture under study with other supernatural females (particularly the dísir) through the close and careful examination of primary source material, thereby proposing a new model of base supernatural femininity for the late Iron Age. The study then goes on to examine how the valkyrjur themselves deviate from this ground state, interrogating various aspects and features associated with them in skaldic, Eddic, prose and iconographic source material as seen through the lens of the hall-based warrior elite, before presenting a new understanding of valkyrja phenomena in this social context: that valkyrjur were used as instruments to propagate the pre-existing social structures of the culture that created and maintained them throughout the late Iron Age. -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

Gram (Mythology)

Gram (mythology) Gram (mythology)'s wiki: In Norse mythology, Gram ( Old Norse Gramr , meaning Wrath) is the sword that Sigurd used to kill the dragon Fafnir. [2] It is primarily used by the Volsungs in the Volsunga Saga . However, it is also seen in other legends Description. Nowhere in the Volsunga Saga is a clear description of Gram given, but there is enough scattered throughout the story to draw a picture of the sword. Sigurd's weapons, Gram included, are described as being âœall decked with gold and gleaming bright." Gram (disambiguation) â” Gram is a unit of measurement of mass. Otherwise, gram may refer to: gram, the Greek based suffix meaning drawing or representation. Contents 1 Places 2 People ⦠Wikipedia. Norse mythology in popular culture â” The Norse mythology, preserved in such ancient Icelandic texts as the Poetic Edda, the Prose Edda, and other lays and sagas, was little known outside Scandinavia until the 19th century. With the widespread publication of Norse myths and legends⦠⦠Wikipedia. Gram (mythology). Quite the same Wikipedia. Just better. In Norse mythology, Gram, (Old Norse Gramr, meaning Wrath)[1] is the sword that Sigurd used to kill the dragon Fafnir.[2]. Description. Gram was forged by Volund; Sigmund received it in the hall of the Völsung after pulling it out of the tree Barnstokkr where Odin placed it. The sword was destroyed in battle when Sigmund struck the spear of an enemy dressed in a black hooded cloak. In Norse mythology, Gram [1] is the sword that Sigurd used to kill the dragon Fafnir.[2] It is primarily used by the Volsungs in the Volsunga Saga. -

School Catchment Areas Order 2O7o

Statutory Document No. 100210 EDUCATION ACT 2OO7 SCHOOL CATCHMENT AREAS ORDER 2O7O Comíng into operøtion L lønuøry 201.0 The Department of Education and Children makes this Order under section 15(a) of the Education Act 2001r. 1 Title This Order is the Sdrool Catchment Areas Order 20L0 and shall come into operation on the l,stlaruary 2011, 2 Commencement This order comes into operation on the l't January 2011 3 Interpretation In this Order "the order maps" means lhreL2maps arurexed to this Order and entitled "Mup No.1 referred to in the School Catchrrrent Areas Order 2010" to "Map No.12 refer¡ed to in the Sclrool Catchment Areas Order 2010 4 Catchment areas of primary schools (1) Úr relation to eadr primary sdrool specified in colrrmn 1 of Sdredule L, the area shown edged with a thick yellow line on one or more of the order maps and indicated by the corresponding nurnber specified in colrrmn 2 of that Sdredule is designated as the catchment area of that sdrool. (2) The parishes constituted for purposes of the Roman Catholic Churdr and annexed to St Anthony's, StJoseph's and StMary's churdres are designated as the catdrment area of St Mary's Roman Catholic School, Douglas. (3) There are no designated catctLment areas for St Thomas' Churdr of England Primary School, Douglas and the Bunscoill Ghaelgagh, StJohn's. t 2oo1 c.33 Price: f,2.00 1 5 Catchment areas of secondary schools (1) Subject to paragraphs (2) and (3), in relation to eadr secondary school specified in column 1 of Sdredule 2, the areas designated by article 2 as the catdrment areas of the corresponding primary sdrools specified in column 2 of that Schedule are together designated as the catchment area of that school. -

Gunther's Head and Hagen's Heart. Royal Sacrifice In

Corpus Mundi. 2020. No 1 От литературного к кинематографическому дискурсу GUNTHER’S HEAD AND HAGEN’S HEART. ROYAL SACRIFICE IN THE LAY OF NIBELUNGS Asya A. Sarakaeva (a) (a) Hainan State University. Haikou, China. Email: asia-lin[at]mail.ru Abstract Thee article deals with the ficnal part of the German epic Nibelungenlied to learn the real significcance, cultural and ideological context of these episodes. Thee author analyzes literary and anthropological theories, as well as archaeological ficnds to conclude that royal deaths described in the epic refliect the ancient practice of human sacrificce. Keywords the Nibelungenlied; the Elder Edda; interpretative level; human sacrificce; intra- communal violence Theis work is licensed under a Creative Commons «Atteribution» ?.0 International License. 135 Corpus Mundi. 2020. No 1 From Literary to Cinematic Discourse ГОЛОВА ГУНТЕРА И СЕРДЦЕ ХАГЕНА. ЖЕРТВОПРИНОШЕНИЕ В «ПЕСНИ О НИБЕЛУНГАХ» Саракаева Ася Алиевна (a) (a) Хайнаньский университет. Хайкоу, Китай. Email: asia-lin[at]mail.ru Аннотация В статье подробному рассмотрению подвергается финальная часть немецкой эпической поэмы «Песнь о нибелунгах», автор ставит себе задачу выяснить подлинное значение, культурный и идеологический контекст этих эпизодов. На основании анализа литературоведческих и антропологических теорий и археологических находок автор приходит к выводу, что гибель королей, описанная в поэме, отражает древную практику человеческих жертвоприношений. Ключевые слова «Песнь о нибелунгах»; «Старшая Эдда»; уровни интерпретации; человеческое жертвоприношение; внутриобщинное насилие Это произведение доступно по лицензии Creative Commons « Atteribution » («Атрибуция») ?.0 Всемирная 136 Corpus Mundi. 2020. No 1 От литературного к кинематографическому дискурсу Thee German epic Nibelungenlied (Thee Lay of Nibelungs) is a unique work of European medieval literature. It can boast a long and elaborate plot, rich imagery and unprecedented for its time psychological insights into human nature, but that’s not what makes it unique. -

Old Norse Mythology and the Ring of the Nibelung

Declaration in lieu of oath: I, Erik Schjeide born on: July 27, 1954 in: Santa Monica, California declare, that I produced this Master Thesis by myself and did not use any sources and resources other than the ones stated and that I did not have any other illegal help, that this Master Thesis has not been presented for examination at any other national or international institution in any shape or form, and that, if this Master Thesis has anything to do with my current employer, I have informed them and asked their permission. Arcata, California, June 15, 2008, Old Norse Mythology and The Ring of the Nibelung Master Thesis zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades “Master of Fine Arts (MFA) New Media” Universitätslehrgang “Master of Fine Arts in New Media” eingereicht am Department für Interaktive Medien und Bildungstechnologien Donau-Universität Krems von Erik Schjeide Krems, July 2008 Betreuer/Betreuerin: Carolyn Guertin Table of Contents I. Abstract 1 II. Introduction 3 III. Wagner’s sources 7 IV. Wagner’s background and The Ring 17 V. Das Rheingold: Mythological beginnings 25 VI. Die Walküre: Odin’s intervention in worldly affairs 34 VII. Siegfried: The hero’s journey 43 VIII. Götterdämmerung: Twilight of the gods 53 IX. Conclusion 65 X. Sources 67 Appendix I: The Psychic Life Cycle as described by Edward Edinger 68 Appendix II: Noteworthy Old Norse mythical deities 69 Appendix III: Noteworthy names in The Volsung Saga 70 Appendix IV: Summary of The Thidrek Saga 72 Old Norse Mythology and The Ring of the Nibelung I. Abstract As an MFA student in New Media, I am creating stop-motion animated short films.