The Maid of Balfe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michael William Balfe Maid of Artois

2A that still attract audiences. There is a touch of lightness in Balfe's work that still endears the Maid of Artois to the attentive listener and which makes it an important contribution to the musical history of this land. John Stewart Allitt Michael William Balfe - nicht nur The Bohemian Girl Eine Neuaufnahme der Maid of Artois bei Campion Cameo Records Der Ire Michael Balfe ("Bolf'sagen unsere britischen Vettern) ist auf dem Kontinent (von dem die Briten immer noch sprechen, wenn sie Europa und nicht sich selber meinen) nur durch sein Bohemian Girl bekannt, das nach dem Krieg Thomas Beecham und nach ihm (sehr bodenlastig und und gar nicht interessant) Richard Bonynge auf CD bei Decca zu Ehren gebracht haben. Das muB gut besetzt sein und hat seine Liingen, vor allem wegen des (bei Decca leider eben nicht vorhandenen) Dialogs. Balfe selber (1808 - 70) war ein interessanter Mann, ein schiiner sogar, der seine Zeit in Italien auch zu (Damen)Bekanntschaften nutzte und der griindlich in der Tradition des Belcanto zu Hause war. Er wuchs als Violinwunderkind in Dublin auf, kam mit 14 nach London und begann seine Karriere als Geiger in Drury Lane, wo er schnell zum Orchesterleiter aufstieg. Ein Miizen in Gestalt von Graf Mazzara brachte ihn nach Paris und dann Italien, wo seine Ausbildung in Mailand stattfand, was sich in einem ercten Ballett ("La P6rouse") fiir die Scala niederschlug. In Paris sang er Rossini mit seiner schcinen Baritonstimme das'Largo al factotum'vor, was diesen beeindruckte und Balfe zu einer Gesangsausbildung zuraten lieB. Dieser trat danach als Rossinis Figaro, auch als Conte in Bellinis Sonnambula in Palermo auf. -

A Unique and Extremely Important Collection of Autograph Letters and Manuscripts of the World's Greatest Composers

z 42 P319u A A I ! 1 i 2 I 3 ! 9 I 5 I 1 i 5 I Collection of Autograph Letters and Manuscripts of the World's Greatest Composers THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES A UNIQUE AND EXTREMELY «!) r IMPORTANT COLLECTION OF AUTOGRAPH LETTERS AND MANUSCRIPTS OF THE WORLD'S GREATEST COMPOSERS 9 J. 'PEARSON & CO. 5, PALLTV1ALL PLACE, LONDON, S.W. Telegraphic and Cable Address: "Parabola, London" ALL THE IT£MS IN THIS" CATALOGUE ARE ENTIRELY FREE OF DUTY Loo<4oC> ^^rsoOj £\* tt^b«* takers s ^ A UNIQUE AND EXTREMELY IMPORTANT COLLECTION OF AUTOGRAPH LETTERS AND MANUSCRIPTS OF THE WORLD'S GREATEST COMPOSERS ON SALE BY J. PEARSON fif CO. 5, PALL MALL PLACE, LONDON, S.W. Telegraphic and Cable Address: " Parabola, London" Wf ALL THE ITEMS IN THIS CATALOGUE ARE ENTIRELY FREE OF DUTY FOREWORD HIS unique and extremely remarkable collection of autograph letters and original manuscripts of the world's greatest composers comprises no less than seventy-five examples. These letters and manuscripts represent the finest pro- curable examples of such supremely important masters as Handel (a splendid manuscript); Mozart (of whom there are two very early letters written when he was only thirteen years old, being addressed to his mother and sister); Bach; Arne; Wagner (a splendid letter of great length); Beethoven ; Gluck (the finest known letter); Haydn; Mendelssohn; Chopin (very important); Brahms; Liszt; Rossini; Meyer- beer; Cherubini; Donizetti; Schubert (a superb letter); Schumann; Spohr; Spontini; Elgar; Gounod, etc. This noble collection is principally based upon the famous Meyer Cohn cabinet. -

Macfarren 2 660306-07 Bk Macfarren 16/08/2011 14:22 Page 16

660306-07 bk Macfarren 2_660306-07 bk Macfarren 16/08/2011 14:22 Page 16 2 CDs George Alexander MACFARREN Robin Hood Spence • Jordan • Ashman • Mackenzie-Wicks Hulbert • Molloy • Hurst • Knox John Powell Singers Victorian Opera Chorus and Orchestra 8.660306-07 16 Ronald Corp 660306-07 bk Macfarren 2_660306-07 bk Macfarren 16/08/2011 14:22 Page 2 George Alexander MACFARREN (1813-1887) Robin Hood A romantic English Opera in three acts Libretto by John Oxenford (1812-1877) Performing Edition by Valerie Langfield Robin Hood (in disguise as Locksley) . Nicky Spence, Tenor Sir Reginald d’Bracy (Sheriff of Nottingham) . George Hulbert, Baritone Hugo (Sompnour, Collector of Abbey dues) . Louis Hurst, Bass Allan-a-Dale (a young peasant) . Andrew Mackenzie-Wicks, Tenor Little John John Molloy, Bass (Outlaws) Much, the Miller’s son} { Alex Knox, Baritone Marian (daughter of Sheriff) . Kay Jordan, Soprano Alice (her attendant) . Magdalen Ashman, Mezzo-soprano Villagers, Citizens and Greenwood men . John Powell Singers and Victorian Opera Chorus Knighted at Windsor Castle on the same day in 1883 George Macfarren was knighted for his services to English music at the same time as Arthur Sullivan, composer (another Royal Academy of Music alumnus), and George Grove, first director of the Victorian Opera Orchestra Royal College of Music and Grove!s Musical Dictionary founder. Ronald Corp Musical Director: Ronald Corp Assistant Conductor: Duncan Ward • Chorus-masters: Marc Hall and John Powell Executive Producer: Raymond J Walker • Research: David Chandler -

The Maid of Artois (Canpion Cameo - Cam€O 2042-3)

L7 Kay Jordan does very well indeed with a title-role straight out of the Guinness Book of Records, the beautiful sounds she makes truly evoke the glamour of its unique progenitor and would have justified this project even if the orchestra and conductor had not been so good. In fact both are excellent. The presentation of the recording, its packaging, its sound quality, its notes with complete libretto, all are first-rate. As an example of resource, of clarity, of sheer resiliance, Victorian Opera from its Northem fastness shows the inert Metropolis what can be done with modest means. Is it too much to hope that the latter will one day learn some lessons? A\ry The Maid of Artois (Canpion Cameo - Cam€o 2042-3) We live in a strange land whcre the collective mind seems to revolve around cars, beer to excess, the latest chipboard kilchens, golf and the media. The remarkable thing is that amidst this cultural desert there are people who care and who have an enthusiasm that often puts oth€l nations io shame. I think of the Avison Ensemble in Newcastle reviving the music of Charles Avison (1709-1790), a fine baroque comlnser who proves that there were others than simply Handel composing music of worth in 'the land without music'. Now we can add to Newcastle, Wilmslow. Wilmslow? Where's that? It's somewhere up North. What good has ever come out of Wilmslow? Quite simply the revival of William Balfe's The Maid ol Artois! But then I guess most people in this educationally impoverished country have never heard of Balfe, less still of his opera composed for Malibran in 1836. -

Public Abstract First Name:Meghan Middle Name:J Last Name:Walsh

Public Abstract First Name:Meghan Middle Name:J Last Name:Walsh Adviser's First Name:Michael Adviser's Last Name:Budds Co-Adviser's First Name: Co-Adviser's Last Name: Graduation Term:SP 2016 Department:Music Degree:MA Title:Bellini's Norma: A Comparative Study of Significant Leading Ladies from Pasta to Callas In the rich tradition of bel canto opera the surviving details surrounding the performances of the leading role from Norma (1831) of Vincenzo Bellini (1801-1835) provide ample basis for a comparison of seven celebrated divas: Giuditta Pasta (1797-1865), Maria Malibran (1808-1836), Giulia Grisi (1811-1869), Thérèse Tietjens (1831-1877), Lilli Lehmann (1848-1929), Rosa Ponselle (1897-1981), and Maria Callas (1923-1977). The bel canto style is considered by many scholars and performers to be one of the most difficult to perfect, with this opera recognized as the zenith of any soprano’s repertory, and yet all seven of these women reigned as the consummate Norma in their time. This study comprises of a chronological comparison of the interpretations of each new genera-tion in order to determine if and how the role of Norma has varied over time. Many singers took on the part prior to Callas, and yet few were praised as frequently and regarded as highly as these leading ladies. Various criticisms have been brought together in this discussion in an effort to create a concrete idea of what these women would have looked and sounded like when singing Norma. The omission of certain bel canto characteristics in the renditions of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries supports the assertion that Maria Callas was instrumental in reviving this operatic tradition in the 1950s.. -

Manon Lescaut : Wagner E Il Settecento

3. MANON LESCAUT : WAGNER E IL SETTECENTO MANON E MANON LESCAUT Ora Puccini era pronto per confrontarsi col capolavoro di Massenet, per di più trattando un soggetto tipicamente francese. Il romanzo di Prévost risaliva al 1731, ed era stato portato all’attenzione dei romantici nel 1820 dall’adattamento drammatico di Étienne Gosse, Manon Lescaut et le chévalier Des Grieux. L’attualità della vicenda stava nella tematica trattata, l’eterno scontro fra vizio e virtù nell’orbita di una passione romantica ante litteram. Non poco peso nella scelta di Puccini dovette avere il fatto che il vero protagonista fosse Des Grieux, in cui poté identificarsi. Prévost finse infatti, come avrebbe fatto Merimée in Carmen, che la storia gli fosse stata raccontata da un giovane sventurato che l’aveva vissuta in prima persona. Ciononostante fu la figura femminile a imporsi fin dal primo importante adattamento per le scene liriche, l’opéra-comique di Scribe per Auber (1856).1 Allo stesso genere apparteneva Manon di Massenet, e anche Puccini dichiarò a Praga che «era sua intenzione musicare un’opera comica nel senso classico della definizione» (ADAMI, pp. 42-3). Le differenze fra i due lavori sono profonde. Manca in Puccini la figura chiave del Conte des Grieux, padre di Renato, che pone fine alla felicità della coppia riprendendosi il figlio con la forza. Solo in conseguenza di questo gesto, di cui è stata forzosamente complice, Manon accetta, con scarso entusiasmo, l’offerta di essere l’amante di Brétigny. Massenet frappone sempre uno schermo galante fra la realtà e la forza dei sentimenti, attribuendo un peso maggiore all’ambiente di nobili e cortigiane in cui gravita la protagonista, mentre Puccini, attenuando il peso delle costrizioni sociali, rende Manon, sazia di 1 In precedenza il soggetto era stato trattato nei due balli pantomimici Manon Lescaut di Jean Pierre Aumer (1830) e di Giovanni Casati (1846), per la musica rispettivamente di Jacques-François-Fromental Halévy e dei fratelli Bellini. -

Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Masters Applied Arts 2018 Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930. David Scott Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appamas Part of the Composition Commons Recommended Citation Scott, D. (2018) Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930.. Masters thesis, DIT, 2018. This Theses, Masters is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900–1930 David Scott, B.Mus. Thesis submitted for the award of M.Phil. to the Dublin Institute of Technology College of Arts and Tourism Supervisor: Dr Mark Fitzgerald Dublin Institute of Technology Conservatory of Music and Drama February 2018 i ABSTRACT Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, arrangements of Irish airs were popularly performed in Victorian drawing rooms and concert venues in both London and Dublin, the most notable publications being Thomas Moore’s collections of Irish Melodies with harmonisations by John Stephenson. Performances of Irish ballads remained popular with English audiences but the publication of Stanford’s song collection An Irish Idyll in Six Miniatures in 1901 by Boosey and Hawkes in London marks a shift to a different type of Irish song. -

(“You Love Opera: We'll Go Twice a Week”), Des Grieux Promise

MANON AT THE OPERA: FROM PRÉVOST’S MANON LESCAUT TO AUBER’S MANON LESCAUT AND MASSENET’S MANON VINCENT GIROUD “Vous aimez l’Opéra: nous irons deux fois la semaine” (“You love opera: we’ll go twice a week”), Des Grieux promises Manon in Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut, as the lovers make plans for their life at Chaillot following their first reconciliation.1 Opera, in turn, has loved Manon, since there exist at least eight operatic versions of the Abbé Prévost’s masterpiece – a record for a modern classic.2 Quickly written in late 1730 and early 1731, the Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut first appeared in Amsterdam as Volume VII of Prévost’s long novel Mémoires d’un homme de qualité.3 An instantaneous success, it went 1 Abbé Prévost, Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut, ed. Frédéric Deloffre and Raymond Picard, Paris: Garnier frères, 1965, 49-50. 2 They are, in chronological order: La courtisane vertueuse, comédie mȇlée d’ariettes four Acts (1772), libretto attributed to César Ribié (1755?-1830?), music from various sources; William Michael Balfe, The Maid of Artois, grand opera in three Acts (1836), libretto by Alfred Bunn; Daniel-François-Esprit Auber, Manon Lescaut, opéra comique in three Acts (1856), libretto by Eugène Scribe; Richard Kleinmichel, Manon, oder das Schloss de l’Orme, romantic-comic opera in four Acts (1887), libretto by Elise Levi; Jules Massenet, Manon, opéra comique in five Acts and six tableaux (1884), libretto by Henri Meilhac and Philippe Gille; Giacomo Puccini, Manon Lescaut, lyrical drama in four Acts (1893), libretto by Domenico Oliva, Giulio Ricordi, Luigi Illica, Giuseppe Giacosa, and Marco Praga; and Hans Werner Henze, Boulevard Solitude, lyric drama in seven Scenes (1951), libretto by Grete Weil on a scenario by Walter Jockisch. -

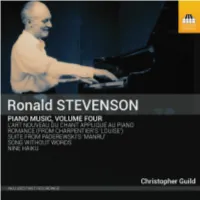

TOCC0555DIGIBKLT.Pdf

RONALD STEVENSON Piano Music, Volume Four Suite from Paderewski’s ‘Manru’ (1961)* 15:08 1 I Introduction and Gipsy March 4:22 2 II Gipsy Song 3:43 3 III Lullaby 2:56 4 IV Cracovienne 4:07 5 Song without Words (1988)* 2:12 Nine Haiku (1971, arr. 2006)* 13:53 6 No. 1 Dedication 1:06 7 No. 2 The Fly 0:50 8 No. 3 Gone Away 2:05 9 No. 4 Nocturne 1:29 10 No. 5 Master and Pupil 0:40 11 No. 6 Spring 1:27 12 Interlude: The Blossoming Cherry (Aubade) 2:12 13 No. 7 Curfew 1:23 14 No. 8 Hiroshima 0:43 15 No. 9 Epilogue 1:58 16 Charpentier: Louise – Romance (c. 1970)* 3:10 2 L’Art Nouveau du chant appliqué au piano (1980–88) 40:53 Volume One 20:44 17 No. 1 Coleridge-taylor: Elëanore (1980) 3:53 18 No. 2 White: So We’ll Go No More A-Roving (1980) 5:52 19 No. 3 Meyerbeer: Romance: Plus blanche que la plus blanche hermine (Les Huguenots) (1975) 5:42 20 No. 4 Rachmaninov: In the Silent Night (1982) 3:17 21 No. 5 Bridge: Go not, happy day! (1980) 2:00 Volume Two 10:09 22 No. 1 Novello: Fly Home, Little Heart (?1980) 3:03 23 No. 2 Novello: We’ll Gather Lilacs (1980) 4:23 24 No. 3 Coleridge-taylor: Demande et Réponse (Hiawatha) (1981) 1:28 25 No. 4 Romberg: Will you remember? (Maytime, ‘Sweethearts’) (1988) 1:15 Volume Three* 10:00 26 No. -

30 Years B a R Toli Dec

EA 0 Y RS 3 Includes B duet with A Cecilia A R Bartoli C T O E C LI D 1 MANUEL GARCÍA 1775–1832 Timing Page 1 Hernando desventurado… Cara gitana del alma mia* 8.30 66 El gitano por amor (Hernando) 2 Yo que soy contrabandista 2.25 68 El poeta calculista (El Poeta) GIOACHINO ROSSINI 1792–1868 3 Sì, ritrovarla io giuro 5.56 70 La Cenerentola (Ramiro) MANUEL GARCÍA 4 Mais que vois-je? Une lyre…Vous dont l’image toujours chère* 6.28 72 La Mort du Tasse (Le Tasse) NICCOLÒ ZINGARELLI 1752–1837 5 Più dubitar mi fan questi suoi detti… Là dai regni dell’ombre, e di morte 4.00 74 Giulietta e Romeo (Everardo) GIOACHINO ROSSINI 6 Principessa, sei tu!… Amor… (Possente nome!) 14.27 76 Armida (Rinaldo) with Cecilia Bartoli (Armida) MANUEL GARCÍA 7 Dieu!… pour venger un père, faut-il devenir assassin? … Ô ciel ! de ma juste furie comment réprimer le transport?* 4.26 86 Florestan ou Le Conseil des dix (Noradin) GIOACHINO ROSSINI 8 Cessa di più resistere 7.57 88 Il barbiere di Siviglia (Il Conte d’Almaviva) MANUEL GARCÍA 9 Formaré mi plan con cuidado 9.51 90 El poeta calculista (El Poeta) GIOACHINO ROSSINI bu S’ella mi è ognor fedele… Qual sarà mai la gioia 7.15 94 Ricciardo e Zoraide (Ricciardo) *World Premiere Recordings JAVIER CAMARENA Tenor CECILIA BARTOLI Mezzo-soprano 6 Les Musiciens du Prince — Monaco Gianluca Capuano 2 3 MENTORED BY BARTOLI Cecilia Bartoli – Music Foundation “Innovation from tradition” The name Cecilia Bartoli stands for breaking new ground, for innovation from tradition, for the revival of forgotten music. -

Citation for Cecilia Bartoli Honorary Conferring Presented by Professor Harry White, UCD School of Music

Citation for Cecilia Bartoli Honorary Conferring Presented by Professor Harry White, UCD School of Music President, Your Excellencies, distinguished guests and colleagues: it is a supreme privilege as well as a great pleasure to present Cecilia Bartoli to you today and to welcome her most warmly to University College Dublin. Although this great artist has been showered with honours from France, Spain, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and of course from Italy, this is the first occasion, so far as I am aware, that she has consented to accept the degree of Doctor of Music, honoris causa. On that account alone, it is especially fitting that she should appear in this capacity solo e pensoso, and that the University should assemble this convocation especially in her honour. As everyone here will know, the acclaim which has greeted this uniquely gifted, uniquely thoughtful Roman Ambassador of music throughout Europe and North America rests upon her recordings, her recitals and her appearances in the great opera houses of the world over the past two decades. But the fame which Cecilia Bartoli enjoys as one of the greatest singers of the age – attested by the stupendous success of her recordings which have made her the best-selling classical artist of her day – is more than a matter of supreme artistry. The triumph of popular culture in general, and of popular musical culture in particular makes it all the more remarkable that Cecilia Bartoli’s voice, lustrous, beautiful and incomparable in terms of technique and expression, should be heard above this clamour by millions of ordinary people. -

Abao-Olbe Presenta Manon Lescaut Protagonizada Por Ainhoa Arteta Y Gregory Kunde

Ópera patrocinada por: ABAO-OLBE PRESENTA MANON LESCAUT PROTAGONIZADA POR AINHOA ARTETA Y GREGORY KUNDE • Debut de Pedro Halffter al frente de la Euskadiko Orkestra Sinfonikoa • Producción procedente del Teatro Regio di Parma, ideada por Stephen Medcalf Bilbao, 16 de febrero de 2016.- ABAO-OLBE (Asociación Bilbaína de Amigos de la Ópera) recupera tras trece años desde su última representación Manon Lescaut de Puccini. Los días 20, 23, 26 y 29 de febrero, con el patrocinio de la Diputación Foral de Bizkaia, sube a escena esta fascinante y trágica historia que encumbró al maestro toscano como uno de los referentes de la escuela verista. La pasión, la virtud, el deseo, la templanza y el amor desesperado y urgente de la juventud atraviesan las escenas de esta tragedia lírica inspirada en un personaje literario considerado uno de los grandes mitos de la historia moderna: la mujer fatal. Manon es una mujer que posee una personalidad magnética y se mueve entre la ingenuidad, la falta de moral, la ternura y el engaño llevando la desgracia a sí misma y a quienes la rodean. Para dar vida a los personajes de esta ópera, ABAO-OLBE ha reunido un elenco encabezado por la soprano guipuzcoana Ainhoa Arteta, recientemente galardonada con la Medalla de Oro al Mérito de las Bellas Artes, quien regresa a Bilbao para poner voz a ‘Manon Lescaut’. A su lado y completando el dúo protagonista el tenor norteamericano Gregory Kunde, distinguido como mejor cantante masculino en los Premios Líricos Teatro Campoamor por su interpretación de ‘Canio’ y ‘Turiddu’ en la producción de ABAO de Cavalleria Rusticana y Pagliacci entre otras, se hace cargo del rol del enamorado ‘Renato des Grieux’.