March-24-Barbiere.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Petite Messe Solennelle

Altrincham Choral Society Rossini Petite Messe Solennelle Steven Roberts Conductor Lydia Bryan Piano Jeffrey Makinson Chamber organ Emma Morwood Soprano Carolina Krogius Mezzo-soprano John Pierce Tenor Thomas Eaglen Bass Royal Northern College of Music Saturday 13th November 2010 Altrincham7.30 Choral p.m. Society Altrincham Choral Society Brenda Adams Bill Hetherington Ian Provost Joy Anderson Jane Hollinshead Linley Roach * Sara Apps Catherine Horrocks * Doris Robinson * Pat Arnold * Valerie Hotter Kate Robinson Ann Ashby Gail Hunt Christine Ross Joyce Astill * Rosemary Hurley Jenny Ruff Kate Barlow Karen Jarmany Stephen Secretan Janet Bedell Elizabeth Jones # Fiona Simpson Laura Booth Rodney Jones Isabel Sinagola Frances Broad * John King-Hele * Susan Sinagola Anne Bullock George Kistruck Isobel Singleton Anthony Campion Elisabeth Lawrence Colin Skelton * John Charlton * Jan Lees Audrey Smallridge # Barbara Clift * John Lees David Swindlehurst Barbara Coombs * Gill Leigh Audrey Taylor * Michael Cummings Keith Lewis Brian Taylor Adrienne Davies Annie Lloyd-Walker Elizabeth Taylor Jacqueline Davies Emma Loat Adrienne Thompson Marie Dixon Rosie Lucas * Ted Thompson * Jean Drape * Sarah Lucas Pamela Thomson Richard Dyson Gavin McBride Jane Tilston Kathy Duffy Helen McBride Jean Tragen Liz Foy Tom McGrath Gill Turner Joyce Fuller Hazel Meakin Elaine Van Der Zeil Rima Gasperas Cathy Merrell Joyce Venables ++ Estelle Goodwin Catherine Mottram Catherine Verdin Bryan Goude * Pamela Moult Christine Weekes Ann Grainger John Mulholland Geryl Whitaker -

Press Kit: the Barber of Seville

Press Kit: The Barber of Seville Press Release José Maria Condemi Bio Bryan Nies Bio Synopsis Images: Krassen Karagiozov (as Figaro in The Barber of Seville) José Maria Condemi (stage director) Bryan Nies (conductor) News Release Press contacts: Virginia Perry, 408.437.4463 or 650.799.1341 [email protected] Elizabeth Santana, 408.437.2229 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: December 13, 2010 “Give Us More Barbers!” – Beethoven The Barber of Seville Opera San José presents Rossini’s comic masterpiece SAN JOSÉ, CA— Opera San José continues its 27th Season with Rossini’s delightful comic opera, The Barber of Seville. The charming tale of a clever young woman, her eager lover, and their resourceful accomplice, Figaro, The Barber of Seville is a tuneful testament to all that’s wonderful about fun and romance. Eight performances are scheduled from February 12 through 27 at the California Theatre, 345 South First Street in downtown San José. Tickets are on sale at the Opera San José Box Office, by phone at (408) 437-4450 or online at www.operasj.org. This production of The Barber of Seville is made possible, in part, by a Cultural Affairs Grant from the City of San José. The madcap story unfolds fast and furious in 18th-century Seville, Spain. Young Rosina is a wealthy orphan and the ward of a grasping old codger, Dr. Bartolo, who is plotting to marry her not only for her beauty, but for her substantial dowry. However, Rosina has two things on her side: the handsome Count Almaviva, who has fallen in love with her, and the town barber, Figaro, her conniving accomplice, who through clever disguises and quick wit succeeds in securing victory for the young couple. -

William Kentridge Brings 'Wozzeck' Into the Trenches

William Kentridge Brings ‘Wozzeck’ Into the Trenches The artist’s production of Berg’s brutal opera, updated to World War I, has come to the Metropolitan Opera. By Jason Farago (December 26, 2019) ”Credit...Devin Yalkin for The New York Times Three years ago, on a trip to Johannesburg, I had the chance to watch the artist William Kentridge working on a new production of Alban Berg’s knifelike opera “Wozzeck.” With a troupe of South African performers, Mr. Kentridge blocked out scenes from this bleak tale of a soldier driven to madness and murder — whose setting he was updating to the years around World War I, when it was written, through the hand-drawn animations and low-tech costumes that Metropolitan Opera audiences have seen in his stagings of Berg’s “Lulu” and Shostakovich’s “The Nose.” Some of what I saw in Mr. Kentridge’s studio has survived in “Wozzeck,” which opens at the Met on Friday. But he often works on multiple projects at once, and much of the material instead ended up in “The Head and the Load,” a historical pageant about the impact of World War I in Africa, which New York audiences saw last year at the Park Avenue Armory. Mr. Kentridge’s “Wozzeck” premiered at the Salzburg Festival in 2017. Zachary Woolfe of The New York Times called it “his most elegant and powerful operatic treatment yet.” At the Met, the Swedish baritone Peter Mattei will sing the title role for the first time; Elza van den Heever, like Mr. Kentridge from Johannesburg, plays his common-law wife, Marie; and Yannick Nézet- Séguin, the company’s music director, will conduct. -

The American Opera Series May 16 – November 28, 2015

The American Opera Series May 16 – November 28, 2015 The WFMT Radio Network is proud to make the American Opera Series available to our affiliates. The American Opera Series is designed to complement the Metropolitan Opera Broadcasts, filling in the schedule to complete the year. This year the American Opera Series features great performances by the Lyric Opera of Chicago, LA Opera, San Francisco Opera, Glimmerglass Festival and Opera Southwest. The American Opera Series for 2015 will bring distinction to your station’s schedule, and unmatched enjoyment to your listeners. Highlights of the American Opera Series include: • The American Opera Series celebrates the Fourth of July (which falls on a Saturday) with Lyric Opera of Chicago’s stellar production of George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess. • LA Opera brings us The Figaro Trilogy, including Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, Rossini’s The Barber of Seville, and John Corigliano’s The Ghosts of Versailles. • The world premiere of Marco Tutino’s Two Women (La Ciociara) starring Anna Caterina Antonacci, based on the novel by Alberto Moravia that became a classic film, staged by San Francisco Opera. • Opera Southwest’s notable reconstruction of Franco Faccio’s 1865 opera Amleto (Hamlet), believed lost for over 135 years, in its American premiere. In addition, this season we’re pleased to announce that we are now including multimedia assets for use on your station’s website and publications! You can find the supplemental materials at the following link: American Opera Series Supplemental Materials Please note: If you have trouble accessing the supplemental materials, please send me an email at [email protected] Program Hours* Weeks Code Start Date Lyric Opera of Chicago 3 - 5 9 LOC 5/16/15 LA Opera 2 ½ - 3 ¼ 6 LAO 7/18/15 San Francisco Opera 1 ¾ - 4 ¾ 10 SFO 8/29/15 Glimmerglass Festival 3 - 3 ½ 3 GLI 11/7/15 Opera Southwest Presents: Amleto 3 1 OSW 11/28/15 Los Angeles Opera’s Production of The Ghosts of Versailles Credit: Craig Henry *Please note: all timings are approximate, and actual times will vary. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 121, 2001-2002

2001-2002 SEASON BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Saluting Seiji Ozawa in his farewell season SEIJI OZAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR Bring your Steinway: With floor plans from 2,300 Phase One of this magnificent to over 5,000 square feet, property is 100% sold and you can bring your Concert occupied. Phase Two is now Grand to Longyear. being offered by Sotheby's Enjoy full-service, single- International Realty and floor condominium living at its Hammond Residential Real absolute finest, all harmoniously Estate. Priced from $1,500,000. located on an extraordinary eight-acre Call Hammond Real Estate at gated community atop prestigious (617) 731-4644, ext. 410. Fisher Hill. LONGYEAR. at ^Jrisner Jiill BROOKLINE CORT1 SOTHEBY'S PROPERTIES INC. International Realty E A L ESTATE Somethingfor any occasion.. &* m y-^ ;fe mwm&m <*-iMF--%^ h : S-i'ffi- I C'?t m^^a»f * • H ^ >{V&^I> ^K S8 ^ r" • >-*f &a Davic^Company Sellers & Collectors of Beautiful Jewelry 232 Boylston Street, Chestnut Hill, MA 02467 617-969-6262 (Tel) 1-800-DAVIDCO 617-969-3434 (Fax) www.davidnndcompany.com . Every car has its moment. This one has thousands per second. .-:.: % - The new 3 Series. Pure drive, The New ^m BMW 3 Series ^f^rn^w^ From $27,745* fop 9 Test drive The Ultimate Driving Machine bmwusa.com The Ultimate at your authorized BMW center 1-8QG-334-4BMW Driving Machine* Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Ray and Maria Stata Music Directorship Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Twenty-first Season, 2001-02 SALUTING SEIJI OZAWA IN HIS FAREWELL SEASON Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. -

Opera Enormous: Arias in the Cinema Benjamin Speed

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 5-2012 Opera Enormous: Arias in the Cinema Benjamin Speed Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Speed, Benjamin, "Opera Enormous: Arias in the Cinema" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1749. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/1749 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. OPERA ENORMOUS: ARIAS IN THE CINEMA By Benjamin Speed B. A. , The Evergreen State College, 2002 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in Communication) The Graduate School The University of Maine May, 2012 Advisory Committee: Nathan Stormer, Associate Professor of Communication and Journalism, Advisor Laura Lindenfeld, Associate Professor of Communication and Journalism and the Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center Michael Socolow, Associate Professor of Communication and Journalism THESIS ACCEPTANCE STATEMENT On behalf of the Graduate Committee for Benjamin Jon Speed I affirm that this manuscript is the final and accepted thesis. Signatures of all committee members are on file with the Graduate School at the University of Maine, 42 Stodder -

CINDERELLA Websites

GIOACHINO ROSSINIʼS CINDERELLA Links to resources and lesson plans related to Rossiniʼs opera, Cinderella. The Aria Database: La Cenerentola http://www.aria- database.com/search.php?sid=e2dbb31103303fb8f096f9929cf13345&X=1&dT=Full&fC=1&searching=yes&t0=all &s0=Cenerentola&f0=keyword&dS=arias Information on 9 arias for La Cenerentola, including roles, voice parts, vocal range, synopsisi, with aria libretto and translation. Great Performances at the Met: La Cenerentola http://www.pbs.org/wnet/gperf/gp-at-the-met-la-cenerentola/3461/ Joyce DiDonato sings the title role in Rossiniʼs Cinderella story, La Cenerentola, with bel canto master Juan Diego Flórez as her dashing prince. The Guardian: Glyndebourne: La Cenerentola's storm scene - video http://www.theguardian.com/music/video/2012/jun/18/glyndebourne-2012-la-cenerentola-video Watch the storm scene in this extract from Glyndebourne's 2005 production of Rossini's La Cenerentola, directed by Peter Hall. IMSLP / Petrucci Music Library: La Cenerentola http://imslp.org/wiki/La_cenerentola_(Rossini,_Gioacchino) Read online or download full music scores and vocal scores for La Cenerentola, music by Gioacchino Rossini. Internet Archive: La Ceniecineta: opera en tres actos https://archive.org/details/lacenicientaoper443ferr Spanish Translation of La Cenerentola, 1916. Internet Archive: La Cenerentola: Dramma Giocoso in Due Atti (published 1860) https://archive.org/stream/lacenerentoladra00ross_0#page/n1/mode/2up Read online or download .pdf of libretto for Rossiniʼs opera, La Cenerentola. In Italian with English Translation. The Kennedy Center: Washington National Opera: La Cenerentola https://www.kennedy-center.org/events/?event=OPOSD Francesca Zambello discusses Rossiniʼs opera, Cinderella. Lyric Opera of Chicago: Cinderella Backstage Pass! https://www.lyricopera.org/uploadedFiles/Education/Children_and_Teens/2011- 12%20OIN%20Backstage%20Pass%20color.pdf Cinderella is featured in Backstage Pass, Lyric Opera of Chicagoʼs student magazine. -

Uot History Freidland.Pdf

Notes for The University of Toronto A History Martin L. Friedland UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2002 Toronto Buffalo London Printed in Canada ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Friedland, M.L. (Martin Lawrence), 1932– Notes for The University of Toronto : a history ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 1. University of Toronto – History – Bibliography. I. Title. LE3.T52F75 2002 Suppl. 378.7139’541 C2002-900419-5 University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the finacial support for its publishing activities of the Government of Canada, through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP). Contents CHAPTER 1 – 1826 – A CHARTER FOR KING’S COLLEGE ..... ............................................. 7 CHAPTER 2 – 1842 – LAYING THE CORNERSTONE ..... ..................................................... 13 CHAPTER 3 – 1849 – THE CREATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO AND TRINITY COLLEGE ............................................................................................... 19 CHAPTER 4 – 1850 – STARTING OVER ..... .......................................................................... -

Naxcat2005 ABRIDGED VERSION

CONTENTS Foreword by Klaus Heymann . 4 Alphabetical List of Works by Composer . 6 Collections . 88 Alphorn 88 Easy Listening 102 Operetta 114 American Classics 88 Flute 106 Orchestral 114 American Jewish Music 88 Funeral Music 106 Organ 117 Ballet 88 Glass Harmonica 106 Piano 118 Baroque 88 Guitar 106 Russian 120 Bassoon 90 Gypsy 109 Samplers 120 Best Of series 90 Harp 109 Saxophone 121 British Music 92 Harpsichord 109 Trombone 121 Cello 92 Horn 109 Tr umpet 121 Chamber Music 93 Light Classics 109 Viennese 122 Chill With 93 Lute 110 Violin 122 Christmas 94 Music for Meditation 110 Vocal and Choral 123 Cinema Classics 96 Oboe 111 Wedding 125 Clarinet 99 Ondes Martenot 111 White Box 125 Early Music 100 Operatic 111 Wind 126 Naxos Jazz . 126 Naxos World . 127 Naxos Educational . 127 Naxos Super Audio CD . 128 Naxos DVD Audio . 129 Naxos DVD . 129 List of Naxos Distributors . 130 Naxos Website: www.naxos.com NaxCat2005 ABRIDGED VERSION2 23/12/2004, 11:54am Symbols used in this catalogue # New release not listed in 2004 Catalogue $ Recording scheduled to be released before 31 March, 2005 † Please note that not all titles are available in all territories. Check with your local distributor for availability. 2 Also available on Mini-Disc (MD)(7.XXXXXX) Reviews and Ratings Over the years, Naxos recordings have received outstanding critical acclaim in virtually every specialized and general-interest publication around the world. In this catalogue we are only listing ratings which summarize a more detailed review in a single number or a single rating. Our recordings receive favourable reviews in many other publications which, however, do not use a simple, easy to understand rating system. -

Tuscia Operafestival™ Brings Italian Style to California IAOF Is Delighted

Tuscia Operafestival™ brings Italian Style to California IAOF is delighted to announce an exciting partnership with Italian luxury brand Bulgari, proud sponsors of the first edition of the “Italian Opera Festival”. Every night before the show will 'offer the public a free taste of the best wines and oils of the tuscia and Italy The Tuscia Operafestival™, now in its sixth season in the historic papal city of Viterbo, will see its Californian debut with the opening of the Italian Opera Festival™ in Orange County, the pearl of Southern California, at the Soka Performing Arts Center of Soka University in Aliso Viejo. The series of events will begin on Saturday, May 26th at 5:00 PM with a press conference hosted by the Italian Cultural Institute (1023 Hilgard Avenue, Los Angeles) and its director, Alberto Di Mauro, and will end on June 2nd, the “Festa della Repubblica”, national Italian holiday commemorating the independence of the Republic of Italy, to be celebrated at the Pico House (430 North Main Street, Los Angeles) in the presence of the Italian Consul General . This new version of our festival strives to promote the excellence of world renowned Italian products such as opera, art, wine, olive oil, water and fashion. The first cultural event, on Wednesday, May 30th at 7:00 PM, at the Soka Performing Arts Center (1 University Drive, Aliso Viejo) will be the recital of international opera star Bruno Praticò: "Buffo si nasce!" (We are Born Funny!), presenting operatic arias and duets by Italian composers Donizetti and Rossini. Recently featured at the LA Opera in the role of "Don Bartolo” in Rossini's Barbiere di Siviglia, Praticò is considered to be one of the greatest comic bass-baritone artists of our time. -

RENT Program

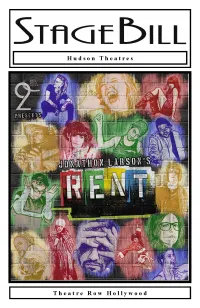

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Remember the first time you were inspired by a performance? The first time that your eyes opened just a little bit wider to try to capture and record everything you were seeing? Maybe it was your first Broadway show, or the first film that really grabbed you. Maybe it was as simple as a third-grade performance. It’s hard to forget that initial sense of wonder and sudden realization that the world might just contain magic . This is the sort of experience the 2Cents Theatre Group is trying to create. Classic performances are hard to define, but easy to spot. Our Goal is to pay homage and respect to the classics, while simultaneously adding our own unique 2 Cents to create a free-standing performance piece that will bemuse, inform, and inspire. 2¢ Theatre Group is in residence at the Hudson Theatre, at 6539 Santa Monica Boulevard. You can catch various talented members of the 2 Cent Crew in our Monthly Cabaret at the Hudson Theatre Café . the second Sunday of each Month. also from 2Cents AT THE HUDSON… TICKETS ON SALE NOW! May 30 - June 30 EACH WEEK FEATURING LIVE PRE-SHOW MUSIC BY: Thurs 5/30 - Stage 11 Sun 6/2 - Anderson William Thurs 6/6 - 30 North SuN 6/9 - Kelli Debbs Thurs 6/13 - TBD Sun 6/16 - Lee Wahlert Thurs 6/20 - TBD Sun 6/23 - TBD Thurs 6/27 - Fire Chief Charlie Sun 6/30 - Chris Duquee Cody Lyman Kristen Boulé & 2Cents Theatre Board of Directors with Michael Abramson at the Hudson Theatres present Book, Music & Lyrics by Jonathan Larson Dedrick Bonner Kate Bowman Amber Bracken Ariel Jean Brooker Brian -

Staged Treasures

Italian opera. Staged treasures. Gaetano Donizetti, Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini and Gioacchino Rossini © HNH International Ltd CATALOGUE # COMPOSER TITLE FEATURED ARTISTS FORMAT UPC Naxos Itxaro Mentxaka, Sondra Radvanovsky, Silvia Vázquez, Soprano / 2.110270 Arturo Chacon-Cruz, Plácido Domingo, Tenor / Roberto Accurso, DVD ALFANO, Franco Carmelo Corrado Caruso, Rodney Gilfry, Baritone / Juan Jose 7 47313 52705 2 Cyrano de Bergerac (1875–1954) Navarro Bass-baritone / Javier Franco, Nahuel di Pierro, Miguel Sola, Bass / Valencia Regional Government Choir / NBD0005 Valencian Community Orchestra / Patrick Fournillier Blu-ray 7 30099 00056 7 Silvia Dalla Benetta, Soprano / Maxim Mironov, Gheorghe Vlad, Tenor / Luca Dall’Amico, Zong Shi, Bass / Vittorio Prato, Baritone / 8.660417-18 Bianca e Gernando 2 Discs Marina Viotti, Mar Campo, Mezzo-soprano / Poznan Camerata Bach 7 30099 04177 5 Choir / Virtuosi Brunensis / Antonino Fogliani 8.550605 Favourite Soprano Arias Luba Orgonášová, Soprano / Slovak RSO / Will Humburg Disc 0 730099 560528 Maria Callas, Rina Cavallari, Gina Cigna, Rosa Ponselle, Soprano / Irene Minghini-Cattaneo, Ebe Stignani, Mezzo-soprano / Marion Telva, Contralto / Giovanni Breviario, Paolo Caroli, Mario Filippeschi, Francesco Merli, Tenor / Tancredi Pasero, 8.110325-27 Norma [3 Discs] 3 Discs Ezio Pinza, Nicola Rossi-Lemeni, Bass / Italian Broadcasting Authority Chorus and Orchestra, Turin / Milan La Scala Chorus and 0 636943 132524 Orchestra / New York Metropolitan Opera Chorus and Orchestra / BELLINI, Vincenzo Vittorio