Adventures in the Netherlands Spotify, Piracy and the New Dutch Experience Adventures in the Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UI Fêtes Dodge in Farewell Event

MONDAY, JULY 24, 2017 THE INDEPENDENT DAILY NEWSPAPER FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA COMMUNITY SINCE 1868 DAILYIOWAN.COM 50¢ News To Know UI fêtes Dodge in farewell event Georgina Dodge will leave her position as chief diversity officer at the University of Iowa for a job at New chairman of Iowa Democratic Party Bucknell University. named By MOLLY HUNTER | [email protected] Former Democratic party executive Troy Price was chosen as Derek Eadon’s Career Highlights successor as chairman of the Iowa Democratic Party on July 22. · She serves on the national board The Democrats’ state of directors for the Association of central Title IX Administrators. committee chose Price · During her tenure at the UI, after Eadon Dodge served as the chief diversity resigned officer, associate vice president, for medical and Title IX coordinator. reasons. “The road · Before working at the UI for seven Price ahead will years, Dodge spent 14 years at chairman not be easy. Ohio State University, where she We’re facing worked for the Office of Minority opposition at every turn, but Affairs and the Department of I am confident that with the African American and African best volunteers, activists, and candidates, together, we will Studies Community Center. win up and down the ticket,” · Before Ohio State, she served Price said in a statement to a six-year enlistment in the the Des Moines Register. In addition to leading Iowa’s Navy working as an electronics largest LGBTQ advocacy group, technician on communications, One Iowa, Price also worked radar, and meteorological on the presidential campaigns equipment. -

Jacknife Lee

Jacknife Lee It is fair to say that Jacknife Lee has become one of the most sought after and highly influential producers currently at work. Lee’s career has encompassed work with some of the biggest and most influential artists on both sides of the Atlantic in the shape of Taylor Swift, U2, R.E.M., Kasabian, Robbie Williams and Neil Diamond. His work on U2’s “How To Dismantle An Atom Bomb” saw him collect two Grammy Awards in 2006 as well as Producer of the Year at the UK MMF Awards. He was also again Grammy nominated in 2013 for his work on Swift’s multi-million selling album “Red.” Currently working on what looks set to be the biggest album from Scottish alt-rock heroes Twin Atlantic and the debut album from The Gossip’s Beth Ditto, Lee has also produced a handful of tracks on Jake Bugg’s upcoming third album and is just about to commence work with Two Door Cinema Club after their successful collaboration on Beacon two years previously. In 2014, Lee was honoured to be asked to co-produce Neil Diamond’s “Melody Road” album alongside the tremendously talented Don Was. “Melody Road” debuted at #3 in America and #4 in the UK as it received universal critical acclaim. Lee has gained much recognition as a writer producer over the last five years. In 2014 also Lee co write and produced various singles for Kodaline’s second album “Coming Up For Air” which peaked at #2, while he also produced and co-wrote Twin Atlantic’s Radio 1 A-listed singles “Heart and Soul” and “Brothers and Sisters.” In addition, Lee spent some of the year writing and producing track for alternative urban artist Raury. -

Understanding Black Feminism Through the Lens of Beyoncé’S Pop Culture Performance Kathryn M

Seattle aP cific nivU ersity Digital Commons @ SPU Honors Projects University Scholars Spring June 7th, 2018 I Got Hot Sauce In My Bag: Understanding Black Feminism Through The Lens of Beyoncé’s Pop Culture Performance Kathryn M. Butterworth Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post- Colonial Studies Commons Recommended Citation Butterworth, Kathryn M., "I Got Hot Sauce In My Bag: Understanding Black Feminism Through The Lens of Beyoncé’s Pop Culture Performance" (2018). Honors Projects. 81. https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects/81 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the University Scholars at Digital Commons @ SPU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ SPU. I GOT HOT SAUCE IN MY BAG: UNDERSTANDING BLACK FEMINISM THROUGH THE LENS OF BEYONCÉ’S POP CULTURE PREFORMANCE by KATHRYN BUTTERWORTH FACULTY ADVISOR, YELENA BAILEY SECOND READER, CHRISTINE CHANEY A project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University Scholars Program Seattle Pacific University 2018 Approved_________________________________ Date____________________________________ Abstract In this paper I argue that Beyoncé’s visual album, Lemonade, functions as a textual hybrid between poetry, surrealist aesthetics and popular culture—challenging the accepted understanding of cultural production within academia. Furthermore, Lemonade centers black life while presenting mainstream audiences with poetry and avant-garde imagery that challenge dominant views of black womanhood. Using theorists bell hooks, Stuart Hall, Patricia Hill- Collins and Audre Lorde, among others, I argue that Beyoncé’s work challenges the understanding of artistic production while simultaneously fitting within a long tradition of black feminist cultural production. -

Mediamonkey Filelist

MediaMonkey Filelist Track # Artist Title Length Album Year Genre Rating Bitrate Media # Local 1 Kirk Franklin Just For Me 5:11 2019 Gospel 182 Disk Local 2 Kanye West I Love It (Clean) 2:11 2019 Rap 4 128 Disk Closer To My Local 3 Drake 5:14 2014 Rap 3 128 Dreams (Clean) Disk Nellie Tager Local 4 If I Back It Up 3:49 2018 Soul 3 172 Travis Disk Local 5 Ariana Grande The Way 3:56 The Way 1 2013 RnB 2 190 Disk Drop City Yacht Crickets (Remix Local 6 5:16 T.I. Remix (Intro 2013 Rap 128 Club Intro - Clean) Disk In The Lonely I'm Not the Only Local 7 Sam Smith 3:59 Hour (Deluxe 5 2014 Pop 190 One Disk Version) Block Brochure: In This Thang Local 8 E40 3:09 Welcome to the 16 2012 Rap 128 Breh Disk Soil 1, 2 & 3 They Don't Local 9 Rico Love 4:55 1 2014 Rap 182 Know Disk Return Of The Local 10 Mann 3:34 Buzzin' 2011 Rap 3 128 Macc (Remix) Disk Local 11 Trey Songz Unusal 4:00 Chapter V 2012 RnB 128 Disk Sensual Local 12 Snoop Dogg Seduction 5:07 BlissMix 7 2012 Rap 0 201 Disk (BlissMix) Same Damn Local 13 Future Time (Clean 4:49 Pluto 11 2012 Rap 128 Disk Remix) Sun Come Up Local 14 Glasses Malone 3:20 Beach Cruiser 2011 Rap 128 (Clean) Disk I'm On One We the Best Local 15 DJ Khaled 4:59 2 2011 Rap 5 128 (Clean) Forever Disk Local 16 Tessellated Searchin' 2:29 2017 Jazz 2 173 Disk Rahsaan 6 AM (Clean Local 17 3:29 Bleuphoria 2813 2011 RnB 128 Patterson Remix) Disk I Luh Ya Papi Local 18 Jennifer Lopez 2:57 1 2014 Rap 193 (Remix) Disk Local 19 Mary Mary Go Get It 2:24 Go Get It 1 2012 Gospel 4 128 Disk LOVE? [The Local 20 Jennifer Lopez On the -

Psychedelia, the Summer of Love, & Monterey-The Rock Culture of 1967

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2012 Psychedelia, the Summer of Love, & Monterey-The Rock Culture of 1967 James M. Maynard Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the American Film Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, and the American Popular Culture Commons Recommended Citation Maynard, James M., "Psychedelia, the Summer of Love, & Monterey-The Rock Culture of 1967". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2012. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/170 Psychedelia, the Summer of Love, & Monterey-The Rock Culture of 1967 Jamie Maynard American Studies Program Senior Thesis Advisor: Louis P. Masur Spring 2012 1 Table of Contents Introduction..…………………………………………………………………………………4 Chapter One: Developing the niche for rock culture & Monterey as a “savior” of Avant- Garde ideals…………………………………………………………………………………...7 Chapter Two: Building the rock “umbrella” & the “Hippie Aesthetic”……………………24 Chapter Three: The Yin & Yang of early hippie rock & culture—developing the San Francisco rock scene…………………………………………………………………………53 Chapter Four: The British sound, acid rock “unpacked” & the countercultural Mecca of Haight-Ashbury………………………………………………………………………………71 Chapter Five: From whisperings of a revolution to a revolution of 100,000 strong— Monterey Pop………………………………………………………………………………...97 Conclusion: The legacy of rock-culture in 1967 and onward……………………………...123 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………….128 Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………..131 2 For Louis P. Masur and Scott Gac- The best music is essentially there to provide you something to face the world with -The Boss 3 Introduction: “Music is prophetic. It has always been in its essence a herald of times to come. Music is more than an object of study: it is a way of perceiving the world. -

Beyoncé's Lemonade Collaborator Melo-X Gives First Interview on Making of the Album.” Pitchfork, 25 Apr

FACULTADE DE FILOLOXÍA DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOLOXÍA INGLESA GRAO EN INGLÉS: ESTUDOS LINGÜÍSTICOS E LITERARIOS Beyoncé’s Lemonade: “A winner don’t quit” ANDREA PATIÑO DE ARTAZA TFG 2017 Vº Bº COORDINADORA MARÍA FRÍAS RUDOLPHI Table of Contents Abstract 1. Introduction 3 2. Methodology 4 3. Beyonce's Lemonade (2016) 5 3.1 Denial: “Hold Up” 6 3.2 Accountability: “Daddy Lessons” 12 3.3 Hope: “Freedom” 21 3.4 Formation 33 4. Conclusion 44 5. Works Cited 46 Appendix 49 Abstract Beyoncé’s latest album has become an instant social phenomenon worldwide. Given its innovative poetic, visual, musical and socio-politic impact, the famous and controversial African American singer has taken an untraveled road—both personal and professional. The purpose of this essay is to provide a close reading of the poetry, music, lyrics and visuals in four sections from Beyoncé’s critically acclaimed Lemonade (2016). To this end, I have chosen what I believe are the most representative sections of Lemonade together with their respective songs. Thus, I focus on the song “Hold Up” from Denial; “Daddy Lessons” from Accountability, “Freedom” from Hope, and “Formation,” where Beyoncé addresses topics such as infidelity, racism, women’s representation, and racism and inequality. I analyse these topics through a close-reading and interpretation of Warsan Shire’s poetry (a source of inspiration), as well as Beyoncé’s own music, lyrics, and imagery. From this analysis, it is safe to say that Lemonade is a relevant work of art that will perdure in time, since it highlights positive representations of African-Americans, at the same time Beyoncé critically denounces the current racial unrest lived in the USA. -

Julius Wellhausen, Anti-Judaism, and Hebrew Bible Scholarship

religions Article Unapologetic Apologetics: Julius Wellhausen, Anti-Judaism, and Hebrew Bible Scholarship Stacy Davis Department of Religious Studies and Theology Saint Mary’s College, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Julius Wellhausen (1844–1918) is in many ways the ancestor of modern Hebrew Bible scholarship. His Prolegomena to the History of Israel condensed decades of source critical work on the Torah into a documentary hypothesis that is still taught today in almost all Hebrew Bible courses in some form. What is not taught as frequently is the anti-Judaism that underpins his hypothesis. This is in part due to unapologetic apologetics regarding Wellhausen’s bias, combined with the insistence that a nineteenth-century scholar cannot be judged by twenty-first century standards. These calls for compassion are made exclusively by white male scholars, leaving Jewish scholars the solitary task of pointing out Wellhausen’s clear anti-Judaism. In a discipline that is already overwhelmingly white, male and Christian, the minimizing of Wellhausen’s racism suggests two things. First, those who may criticize contextual biblical studies done by women and scholars of color have no problem pleading for a contextual understanding of Wellhausen while downplaying the growing anti-Judaism and nationalism that was a part of nineteenth-century Germany. Second, recent calls for inclusion in the Society of Biblical Literature may be well intentioned but ultimately useless if the guild cannot simply call one of its most brilliant founders the biased man that he was. Keywords: Wellhausen; anti-Judaism; historical context Citation: Davis, Stacy. 2021. Unapologetic Apologetics: Julius Wellhausen, Anti-Judaism, and Hebrew Bible Scholarship. -

Rihanna Loud Deluxe Edition Zip

Rihanna loud deluxe edition zip El Album contiene 13 Canciones · Espero que te guste · Agrega a Tracklist: · S&M · What's My Name (feat. Drake) · Ch Album|Loud (Deluxe. Rihanna – Loud (Deluxe Edition) (Dirty) – - kbps Download Link: Code: Code. Rihanna – Loud (Bonus Track Version), Itunes Plus Full, Rihanna – Loud (Bonus Track Avril Lavigne - Goodbye Lullaby (Special Deluxe Edition) David Guetta. Download CD Loud: Deluxe Edition. by Camilo Fenty 5 comentários. Formato: mp3. Tamanho: 88 MB. S&M What's My Name? feat. Drake Cheers (Drink To That). Rihanna Loud Deluxe Album Free Download Zip > acer aspire one windows xp home edition ulcpc. Aguirre furore di dio. Play and Download all songs on Loud, a music album by Barbados artist Rihanna on rihanna loud full album download zip Download Link . Rihanna - Loud (Deluxe Edition) (). Download Album Rihanna - Loud (Deluxe Edition). Rihanna - Loud (Deluxe - iTunes).7z. MB American Idiot (Deluxe Version) MB .. Keane | Hopes and Fears (Deluxe Edition) [заказ 58]. Zip rihanna loud album boo deluxe Rihanna – ANTi (Album) Zip Results of eminem recovery deluxe edition viperial: Free download software. Download Descargar Cd De Rihanna Loud Deluxe Edition. 7/6/ Download File Rihanna Unapologetic (Deluxe Edition) zip. Login; Sign Up Forgot your. Listen to songs from the album Loud, including "S&M", "What's My Name? (feat. Drake)", "Cheers The Hits Collection, Vol. One (Deluxe Edition with Videos). Escucha canciones del álbum Loud, incluyendo "S&M", "What's My Name? (feat. Drake)" Love the Way You Lie (feat. Rihanna). Recovery (Deluxe Edition). Rihanna keeps on looking Filename: Rihanna - Loud - (Deluxe Edition).zip: Size: MB ( bytes) Report abuse: Uploaded by. -

The Black Vernacular Versus a Cracker's Knack for Verses

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Arts Arts Research & Publications 2014-10-24 The black vernacular versus a cracker's knack for verses Flynn, Darin McFarland Books Flynn, D. (2014). The black vernacular versus a cracker's knack for verses. In S. F. Parker (Ed.). Eminem and Rap, Poetry, Race: Essays (pp. 65-88). Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/112323 book part "Eminem and Rap, Poetry, Race: Essays" © 2014 Edited by Scott F. Parker Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca The Black Vernacular Versus a Cracker’s Knack for Verses Darin Flynn Who would have ever thought that one of the greatest rappers of all would be a white cat? —Ice-T, Something from Nothing: The Art of Rap1 Slim Shady’s psychopathy is worthy of a good slasher movie. The soci- olinguistics and psycholinguistics behind Marshall Mathers and his music, though, are deserving of a PBS documentary. Eminem capitalizes on his lin- guistic genie with as much savvy as he does on his alter egos. He “flips the linguistics,” as he boasts in “Fast Lane” from Bad Meets Evil’s 2011 album Hell: The Sequel. As its title suggests, this essay focuses initially on the fact that rap is deeply rooted in black English, relating this to Eminem in the context of much information on the language of (Detroit) blacks. This linguistic excur- sion may not endear me to readers who hate grammar (or to impatient fans), but it ultimately helps to understand how Eminem and hip hop managed to adopt each other. -

I Will Survive”--Gloria Gaynor (1978) Added to the National Registry: 2015 Essay by Louis Niebur (Guest Post)*

“I Will Survive”--Gloria Gaynor (1978) Added to the National Registry: 2015 Essay by Louis Niebur (guest post)* Gloria Gaynor Original single Original single sleeve On the surface, Gloria Gaynor's disco anthem, "I Will Survive" tells the straightforward story of a woman unwilling to put up with a cheating partner. But immediately upon its release in 1978, it was endowed by listeners with much more power than this simple premise, through its universal themes of strength, pride, independence, and overcoming self-doubt. It had, and continues to have, particular resonance with the groups most closely connected with disco since its creation in the early 1970s: African-Americans, gays, and women. Gaynor's story isn't one of overnight success. Rather, her title as the first "Queen of Discos" was earned after years of struggle as a touring live musician, sacrificing security and stability for the less tangible but more fulfilling rewards of a musical career. Gaynor was born on September 9, 1949 as Gloria Fowles in Newark, New Jersey. After high school, she spent nearly a decade singing in a string of semi-regular nightclub gigs, and touring the chitterling circuit, performing standards alongside the latest Top 40 hits with house bands up and down the east coast. She recorded her first single, “She’ll Be Sorry” for Johnny Nash’s Jocida Records in 1965. Nash also recommended she change her name to the alliterative “Gloria Gaynor,” in the hopes that people would call her by the catchy “G.G.” (a nickname that stuck). Throughout the second half of the 1960s and the first half of the 1970s, she and her band, City Life, achieved some renown with their upbeat disco sound, playing venues around the East and Midwest. -

The Blueprint”--Jay-Z (2001) Added to the National Registry: 2018 Essay by Zack O’Malley Greenburg (Guest Post)*

“The Blueprint”--Jay-Z (2001) Added to the National Registry: 2018 Essay by Zack O’Malley Greenburg (guest post)* Original CD cover A son of Brooklyn’s notorious housing projects who became hip-hop’s first billionaire in 2019, Jay-Z is as close as it gets to the modern-day embodiment of the American dream. So it’s only fitting that “The Blueprint,” one of the most noteworthy albums of the aughts, is the first 21st century recording selected for the National Recording Registry. Jay-Z’s sixth studio album arrived on September 11, 2001, and could have been lost amid the ensuing wave of national mourning. Instead, “Blueprint” ended up as a soundtrack of sorts-- mirroring the heady mix of pride and paranoia that permeated the post-September 11th United States. A classic album in any era, fate deposited it just in time to mirror an American moment when wound-licking gave way to a defiant indomitability. At the time, Jay-Z’s foes included a burgeoning roster of rival rappers, most notably Queens native Nas (a challenger for the King of New York crown) and the justice system, which had placed Jay-Z in legal limbo over the attack of a producer thought to have bootlegged his prior album (Jay-Z would eventually receive probation). He was also years into a prescient Grammy boycott—“Blueprint” would later be shut out at music’s biggest night despite vast critical acclaim. Backed by a battalion of producers including Timbaland, Just Blaze and a young Kanye West, Jay-Z caps “Blueprint’s” opening salvo by pronouncing himself “God MC, me, Jay-Hova.” Though he slings a few barbs at Mobb Deep’s Prodigy, his real target is archrival Nas, who’d questioned Jay-Z’s underworld credentials in a radio freestyle that evolved into one of hip-hop’s most legendary verbal confrontations. -

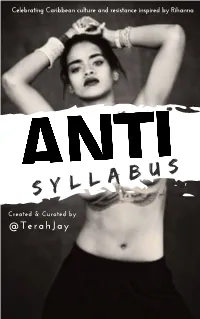

Anti Syllabus

Celebrating Caribbean culture and resistance inspired by Rihanna A B U S S Y L L Created & Curated by @TerahJay ⠠⠗⠊⠓⠁ ⠝⠝⠁⠂ ⠞⠓⠁⠝⠅ ⠽⠕⠥ ⠋⠕⠗ ⠑⠧⠑⠗⠽ ⠞⠓⠊⠝⠛ ⠲ ⠠⠇⠕⠧⠑ y a J h a r e T - . s a y ⠽⠕⠥ w l a u o y e v o L . g n ⠁⠇⠺⠁⠽ i h t y r e v e r o f u o y k ⠎⠂ n a h t a n n a h i R ⠠⠞⠑⠗⠁ ⠓⠠⠚⠁⠽ ⠲ MUST BE LOVE ON THE BRAIN That resistance to conformity, that resistance to needing and pleasing and placating the global marketplace is absolutely very much situated within her context. Anti is actively telling you, song after song, that it's not trying to fit Heather D. Russell On January 28th 2017 Rihanna celebrated her one-year anniversarih, aptly titled ANTiversary. Her highly anticipated 8th studio album was a work of art that upon its release, shifted the course of her craft and career. The eclectic, raw, emotional, album was molecule shifting for Rihanna as well as her fanbase the Rihanna Navy. Rihanna states: "I had no idea how it would be recieved, neither was that something I considered. I just wanted to make a body of work that felt right." In many ways ANTi was not about finding herself as an artist, it was more about creating and re-creating herself as a complete person. Someone unafraid, someone boundless. In her process she trusted the way the music made her feel. As a Black woman from Barbados it is important to situate her life, career, and way of knowing within a specific Caribbean context.