Research Versus Olympiad Questions on the Polymath Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2006 Annual Report

Contents Clay Mathematics Institute 2006 James A. Carlson Letter from the President 2 Recognizing Achievement Fields Medal Winner Terence Tao 3 Persi Diaconis Mathematics & Magic Tricks 4 Annual Meeting Clay Lectures at Cambridge University 6 Researchers, Workshops & Conferences Summary of 2006 Research Activities 8 Profile Interview with Research Fellow Ben Green 10 Davar Khoshnevisan Normal Numbers are Normal 15 Feature Article CMI—Göttingen Library Project: 16 Eugene Chislenko The Felix Klein Protocols Digitized The Klein Protokolle 18 Summer School Arithmetic Geometry at the Mathematisches Institut, Göttingen, Germany 22 Program Overview The Ross Program at Ohio State University 24 PROMYS at Boston University Institute News Awards & Honors 26 Deadlines Nominations, Proposals and Applications 32 Publications Selected Articles by Research Fellows 33 Books & Videos Activities 2007 Institute Calendar 36 2006 Another major change this year concerns the editorial board for the Clay Mathematics Institute Monograph Series, published jointly with the American Mathematical Society. Simon Donaldson and Andrew Wiles will serve as editors-in-chief, while I will serve as managing editor. Associate editors are Brian Conrad, Ingrid Daubechies, Charles Fefferman, János Kollár, Andrei Okounkov, David Morrison, Cliff Taubes, Peter Ozsváth, and Karen Smith. The Monograph Series publishes Letter from the president selected expositions of recent developments, both in emerging areas and in older subjects transformed by new insights or unifying ideas. The next volume in the series will be Ricci Flow and the Poincaré Conjecture, by John Morgan and Gang Tian. Their book will appear in the summer of 2007. In related publishing news, the Institute has had the complete record of the Göttingen seminars of Felix Klein, 1872–1912, digitized and made available on James Carlson. -

A Mathematical Tonic

NATURE|Vol 443|14 September 2006 BOOKS & ARTS reader nonplussed. For instance, he discusses a problem in which a mouse runs at constant A mathematical tonic speed round a circle, and a cat, starting at the centre of the circle, runs at constant speed Dr Euler’s Fabulous Formula: Cures Many mathematician. This is mostly a good thing: directly towards the mouse at all times. Does Mathematical Ills not many mathematicians know much about the cat catch the mouse? Yes, if, and only if, it by Paul Nahin signal processing or the importance of complex runs faster than the mouse. In the middle of Princeton University Press: 2006. 404 pp. numbers to engineers, and it is fascinating to the discussion Nahin suddenly abandons the $29.95, £18.95 find out about these subjects. Furthermore, it mathematics and puts a discrete approximation is likely that a mathematician would have got into his computer to generate some diagrams. Timothy Gowers hung up on details that Nahin cheerfully, and His justification is that an analytic formula for One of the effects of the remarkable success rightly, ignores. However, his background has the cat’s position is hard to obtain, but actu- of Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History Of Time the occasional disadvantage as well, such as ally the problem can be neatly solved without (Bantam, 1988) was a burgeoning of the mar- when he discusses the matrix formulation of such a formula (although it is good to have ket for popular science writing. It did not take de Moivre’s theorem, the fundamental result his diagrams as well). -

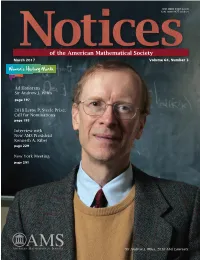

Sir Andrew J. Wiles

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 Volume 64, Number 3 Women's History Month Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Wiles page 197 2018 Leroy P. Steele Prize: Call for Nominations page 195 Interview with New AMS President Kenneth A. Ribet page 229 New York Meeting page 291 Sir Andrew J. Wiles, 2016 Abel Laureate. “The definition of a good mathematical problem is the mathematics it generates rather Notices than the problem itself.” of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 FEATURES 197 239229 26239 Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Interview with New The Graduate Student Wiles AMS President Kenneth Section Interview with Abel Laureate Sir A. Ribet Interview with Ryan Haskett Andrew J. Wiles by Martin Raussen and by Alexander Diaz-Lopez Allyn Jackson Christian Skau WHAT IS...an Elliptic Curve? Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof by by Harris B. Daniels and Álvaro Henri Darmon Lozano-Robledo The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles by Christopher Skinner In this issue we honor Sir Andrew J. Wiles, prover of Fermat's Last Theorem, recipient of the 2016 Abel Prize, and star of the NOVA video The Proof. We've got the official interview, reprinted from the newsletter of our friends in the European Mathematical Society; "Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof" by Henri Darmon; and a collection of articles on "The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles" assembled by guest editor Christopher Skinner. We welcome the new AMS president, Ken Ribet (another star of The Proof). Marcelo Viana, Director of IMPA in Rio, describes "Math in Brazil" on the eve of the upcoming IMO and ICM. -

The Top Mathematics Award

Fields told me and which I later verified in Sweden, namely, that Nobel hated the mathematician Mittag- Leffler and that mathematics would not be one of the do- mains in which the Nobel prizes would The Top Mathematics be available." Award Whatever the reason, Nobel had lit- tle esteem for mathematics. He was Florin Diacuy a practical man who ignored basic re- search. He never understood its impor- tance and long term consequences. But Fields did, and he meant to do his best John Charles Fields to promote it. Fields was born in Hamilton, Ontario in 1863. At the age of 21, he graduated from the University of Toronto Fields Medal with a B.A. in mathematics. Three years later, he fin- ished his Ph.D. at Johns Hopkins University and was then There is no Nobel Prize for mathematics. Its top award, appointed professor at Allegheny College in Pennsylvania, the Fields Medal, bears the name of a Canadian. where he taught from 1889 to 1892. But soon his dream In 1896, the Swedish inventor Al- of pursuing research faded away. North America was not fred Nobel died rich and famous. His ready to fund novel ideas in science. Then, an opportunity will provided for the establishment of to leave for Europe arose. a prize fund. Starting in 1901 the For the next 10 years, Fields studied in Paris and Berlin annual interest was awarded yearly with some of the best mathematicians of his time. Af- for the most important contributions ter feeling accomplished, he returned home|his country to physics, chemistry, physiology or needed him. -

Ten Mathematical Landmarks, 1967–2017

Ten Mathematical Landmarks, 1967{2017 MD-DC-VA Spring Section Meeting Frostburg State University April 29, 2017 Ten Mathematical Landmarks, 1967{2017 Nine, Eight, Seven, and Six Nine: Chaos, Fractals, and the Resurgence of Dynamical Systems Eight: The Explosion of Discrete Mathematics Seven: The Technology Revolution Six: The Classification of Finite Simple Groups Ten Mathematical Landmarks, 1967{2017 Five: The Four-Color Theorem 1852-1976 1852: Francis Guthrie's conjecture: Four colors are sufficient to color any map on the plane in such a way that countries sharing a boundary edge (not merely a corner) must be colored differently. 1878: Arthur Cayley addresses the London Math Society, asks if the Four-Color Theorem has been proved. 1879: A. B. Kempe publishes a proof. 1890: P. J. Heawood notes that Kempe's proof has a serious gap in it, uses same method to prove the Five-Color Theorem for planar maps. The Four-Color Conjecture remains open. 1891: Heawood makes a conjecture about coloring maps on the surfaces of many-holed tori. 1900-1950's: Many attempts to prove the 4CC (Franklin, George Birkhoff, many others) give a jump-start to a certain branch of topology called Graph Theory. The latter becomes very popular. Ten Mathematical Landmarks, 1967{2017 Five: The Four-Color Theorem (4CT) The first proof By the early 1960s, the 4CC was proved for all maps with at most 38 regions. In 1969, H. Heesch developed the two main ingredients needed for the ultimate proof, namely reducibility and discharging. He also introduced the idea of an unavoidable configuration. -

On the Depth of Szemerédi's Theorem

1–13 10.1093/philmat/nku036 Philosophia Mathematica On the Depth of Szemerédi’s Theorem† Andrew Arana Department of Philosophy, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT 5 Many mathematicians have cited depth as an important value in their research. How- ever, there is no single, widely accepted account of mathematical depth. This article is an attempt to bridge this gap. The strategy is to begin with a discussion of Szemerédi’s theorem, which says that each subset of the natural numbers that is sufficiently dense contains an arithmetical progression of arbitrary length. This theorem has been judged 10 deepbymanymathematicians,andsomakesforagood caseonwhichtofocusinanalyz- ing mathematical depth. After introducing the theorem, four accounts of mathematical depth will be considered. Mathematicians frequently cite depth as an important value for their research. A perusal of the archives of just the Annals of Mathematics since the 1920s reveals 15 more than a hundred articles employing the modifier ‘deep’, referring to deep results, theorems, conjectures, questions, consequences, methods, insights, connections, and analyses. However, there is no single, widely-shared understanding of what mathemat- ical depth consists in. This article is a modest attempt to bring some coherence to mathematicians’ understandings of depth, as a preliminary to determining more pre- 20 cisely what its value is. I make no attempt at completeness here; there are many more understandings of depth in the mathematical literature than I have categorized here, indeed so many as to cast doubt on the notion that depth is a single phenomenon at all. -

Sir Timothy Gowers Interview

THE GRADUATE STUDENT SECTION Interview with Sir Timothy Gowers early. At the age of sixteen I was already doing just math and physics. Then, going to university, I had to choose one subject and that subject was clearly going to be mathematics. Later, when I had the chance to specialize in either pure or applied, it was clear to me that pure is what I wanted to do, and at each stage I wanted to get to the next stage, so if you continue that process then, by induction, you end up as a mathematician. Diaz-Lopez: Who encouraged or inspired you? Gowers: I had a particularly good primary school teacher who told us about π when we were five years old. Then, when I went to my next primary school, the wife of the headmaster was a Cambridge math graduate and she also told us about things that went well beyond the things we were supposed to be learning. After primary school, again I had somebody who was maybe overqualified for the job, somebody who had been a fellow of King’s College in Cambridge in mathematics and then decided to switch to school teaching and was very inspiring. Finally, when I went to Cambridge, my director of studies was Béla Bol- lobás, who went on to become my research supervisor and was also a very inspiring mathematician. Diaz-Lopez: How would you describe your research to a graduate student? Gowers: The area that I mainly work in is additive combinatorics. I am drawn to combinatorics because I like problems with elementary statements, problems you can attack with elementary-ish methods, by which I mean ones where in order to start you don’t have to spend two years Sir Timothy Gowers is professor of mathematics reading literature. -

The Polymath Project: Lessons from a Successful Online Collaboration in Mathematics

The Polymath Project: Lessons from a Successful Online Collaboration in Mathematics Justin Cranshaw Aniket Kittur School of Computer Science School of Computer Science Carnegie Mellon University Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA, USA Pittsburgh, PA, USA [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT and prior knowledge, and they have high coordination de- Although science is becoming increasingly collaborative, mands. Furthermore, professional advancement in science there are remarkably few success stories of online collab- is typically subject to a highly developed and closed-loop orations between professional scientists that actually result reward structure (e.g., publications, grants, tenure). These in real discoveries. A notable exception is the Polymath factors do not align well with the open, asynchronous, in- Project, a group of mathematicians who collaborate online to dependent, peer production systems that have typified social solve open mathematics problems. We provide an in-depth collaboration online. However, one notable exception is the descriptive history of Polymath, using data analysis and vi- Polymath Project, a collection of mathematicians ranging in sualization to elucidate the principles that led to its success, expertise from Fields Medal winners to high school math- and the difficulties that must be addressed before the project ematics teachers who collaborate online to prove unsolved can be scaled up. We find that although a small percentage mathematical conjectures. of users created most of the content, almost all users never- theless contributed some content that was highly influential There are many reasons to believe why mathematics might to the task at hand. We also find that leadership played an be well suited for large-scale online collaboration. -

Should Mathematicians Care About Communicating to Broad Audiences? Theory and Practice

Panel discussion organised by the European Mathematical Society (EMS) Should mathematicians care about communicating to broad audiences? Theory and practice Transcription coordinated by Jean-Pierre Bourguignon, CNRS-IHÉS, Bures-sur-Yvette, France In most countries, mathematics is not present in the media at par with other basic sciences. This is especially true regarding the communication of outstanding new results, their significance and perspectives of development of the field. The main purpose of the panel discussion, an EMS initiative, that took place at the ICM on Wednesday, August 23, between 6 and 8 p.m., was to nurture the debate on whether communicating about mathematics, as a thriving part of science, is needed, and how such a communication can be efficiently tuned to different audiences and a variety of circumstances. For that purpose, the EMS Executive Committee set up a committee consisting of Jean-Pierre Bourguignon (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and In- stitut des Hautes Études Scientifiques, Bures-sur-Yvette, France), Olga Gil-Medrano (Universitat de València, Spain), Ari Laptev (Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan, Stock- holm, Sweden), and Marta Sanz-Solé (Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain) to prepare the event and select the panelists. Jean-Pierre Bourguignon was asked more specifically to prepare the event with the panelists and to moderate the discussion itself. These proceedings include a revised version of the presentations made by the panelists under their signature, and a brief outline of the discussion that took place after their presentations. A contribution that was later elaborated by a participant from the floor has been added separately from the discussion. -

Reviewed by John P. Burgess Why Is There Philosophy of Mathematics At

Why is There Philosophy of Mathematics at All? Reviewed by John P. Burgess Why is There Philosophy of Mathematics At All? Ian Hacking Cambridge, 2014, xv + 290 pp., US$ 80.00 (hardcover), 27.99 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-107-05017-4, 978-1-107-65815-8 In his latest book, the noted philosopher of science Ian Hacking turns his attention to mathematics, a long-standing interest of his, heretofore seldom indulged. His previous work, though it hasn’t always been universally found convincing, has been unfailingly provocative. The present work fits the pattern. Some mathematicians seeing the title of Hacking’s latest book may read it as meaning something like, “Why can’t we just get rid of philosophy mathematics?” asked in a tone of voice suggesting that it would be a very good thing if we could. After all, did not Hilbert himself announce, speaking of foundational questions, that what he wanted to do with them was to get rid once and for all [einfürallemal aus der Welt zu schaffen] of them? But this is not what is intended. Hacking doesn’t think philosophy of mathematics will ever go away for good, be got rid of once and for all, and he genuinely means to ask why this is so: What is it about mathematics that historically has kept drawing philosophers back to it, time and again? The answer suggested is that there are two factors at work. One is the experience of following a compelling proof. The seeming inevitability of the conclusion, the feeling that it is not something one is free to take or leave as one chooses, Hacking cites as an ultimate motivation behind philosophies that affirm the independent reality of a realm of mathematical facts, from Plato to Hardy [3]. -

The Early Career of G.H. Hardy

THE EARLY CAREER OF G.H. HARDY by Brenda Davison B.A.Sc.(hons), University of British Columbia, 1989 a Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Department of Mathematics c Brenda Davison 2010 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2010 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for Fair Dealing. Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. APPROVAL Name: Brenda Davison Degree: Master of Science Title of Thesis: The Early Career of G.H. Hardy Examining Committee: Dr. Veselin Jungić Chair Dr. W. Tom Archibald, Senior Supervisor Dr. Len Berggren, Supervisor Dr. Nilima Nigam, External Examiner Date Approved: ii Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the “Institutional Repository” link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

De Morgan Association NEWSLETTER

UCL DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS NEWSLETTER 2014 De Morgan Association NEWSLETTER The Year in the Department At the time of writing the UCL community is the announcement of this year’s Fields celebrating the success of the award of the Medallists, the odds are truly astronomical-think Nobel Prize in Medicine to Professor John of tossing a coin 5 times and getting tails each O’Keefe of UCL’s Sainsbury Wellcome Centre for time until a head on the last toss! Clearly there is Neural Circuits & Behaviour. Professor O’Keefe a deep problem here which goes far beyond the becomes the 29th Nobel Laureate among UCL’s simple tossing of coins and into considerations academics and students and joins the winner of of role models, social attitudes, unconscious bias the 201 Nobel Prize in Physics, Professor Peter and so on. Higgs, who was for a brief period a Lecturer in the Department of Mathematics. There is, of Fifty percent of UCL’s undergraduates and MSc course, no Nobel Prize in Mathematics but with students studying mathematics are female and UCL’s and the department’s commitment to inter- the level of attainment of these male and female disciplinary research in, for example, applying students is indistinguishable. It is beyond this mathematics to medicine and neuro-imaging, it degree level where it becomes evident that is not inconceivable that one day the department there is a problem in the progression of women will celebrate one of its own becoming a Nobel mathematicians: the so-called ‘leaky pipeline’. Laureate. At UCL Mathematics, 20% of our PhD students and postdoctoral researchers are women, and But there is a prize of similar standing in only 4 of our 48 permanent academic staff are Mathematics: the Fields Medal.