Characters with Intellectual Disability in Short Science Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IRS for ANZAPA

- 2 for ANZAPA #267 - J u n e 2012 and for display on eFanzines (www.efanzines.com) o-o-o Contents This issue’s cover .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 The Lady Varnishes ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Vale Ray Bradbury (1920-2012) ................................................................................................................................... 5 Letters from (North) America....................................................................................................................................... 7 Conventions held and on the horizon ............................................................................................................................ 9 Awards at the Natcon – Sunday evening 10th June 2012 .......................................................................................... 12 Hugo Awards - 2012 nominations ............................................................................................................................. 16 Fan Funds represented or commented on at Continuum 8 ...................................................................................... 19 Surinam Turtles - trade paperbacks online for US$18.00 from Ramble House: http://www.ramblehouse.com..... 21 Book review – ‘A Kingdom Besieged’ by Raymond E Feist (in his -

Letter from the Chair Symposium Committee

Letter from the Chair Welcome to the Life, the Universe, & Everything Sym- statement I’ve ever made, but I stand by it. Over the posium on Science Fiction and Fantasy, or as we affec- next three days I advise you to do two things: learn tionately call it, LTUE. If you’re here for the first, tenth, everything you can and have an amazing time doing it. or the thirty-fourth time (or any number of years in- I’ve frequently been told by our attendees how much between), I sincerely hope you’ll find this weekend to be LTUE means to them. Between gushing about amaz- not just enjoyable but sensational. ing experiences with our panelists, as well as with other I’d like to start out by thanking each and every one of attendees, they often reference some sort of energy that you for being here. Whether you’re here as an attendee, LTUE seems to give them. This energy inspires them to a presenter, or a volunteer, your presence is incredibly get up and create something. This year the committee important to the LTUE experience. While the sympo- has poured countless hours of energy into this year’s pro- sium as an idea will always exist, without people who gramming, and I hope you each get every ounce of energy are willing to be here LTUE would cease to exist. I out that you can. I hope that by the end of this year’s would like to particularly express my gratitude to the symposium you find yourself ready to take on anything. -

No. 3 / May 2014 Ecdysis Masthead

No. 3 / May 2014 Ecdysis Masthead Ecdysis No. 3 / May 2014 Jonathan Crowe editor Zvi Gilbert Jennifer Seely art Tamara Vardomskaya Send hate mail, letters of comment, and submissions to: All content is copyright © their respective contributors. mail PO Box 473 Shawville QC J0X 2Y0 Photo/illustration credits: [1, 8, 17, 19, 24] Art by CANADA Jennifer Seely. [25] Photo of Samuel R. Delany by e-mail [email protected] Houari B., and used under the terms of its Creative web mcwetboy.net/ecdysis Commons Licence. 2 Some Twitter responses to a mass e-mail begging fellow SFWA members for a Nebula nomination in early January 2014. EDITORIAL The Value of Awards I’ll be honest: I have ambivalent feelings ess, or whether the wrong works or individu- about awards. als were nominated, or whether the wrong On the one hand, I find awards useful: works or individuals won, as so many fans when so much is published in science fiction seem to do every year. and fantasy every year, they serve to winnow No, the problem I have with awards is the wheat from the chaff. For the past few how much we talk about them, and how im- years I’ve made a point of reading as many of portant we make them. the award nominees as possible, even if I’m Which is to say: too much and too much. not in a position to vote for them. One problem with awards is that there But on the other hand, I find awards an- are so many of them. -

LONDON in 2014 London Docklands, 14-18 August 2014

LONDON IN 2014 www.Londonin20l4.org London Docklands, 14-18 August 2014 A bid for the 72nd World Science Fiction Convention Email: [email protected] Twitter: @Londonln20l4 F *1 ,1. a. W * W WHY LONDON? SUPPORT THE BID We’re excited by the opportunity to bring the You can support us online at our website. Worldcon back to London after a gap of forty- nine years. London Is the largest and most Pre-Supports are £12 I US$20 diverse city in Western Europe, and is home to Friends are £60 I US$100 the UK publishing and media industries. A London Young Friends are £30 I US$50 Worldcon will be a very special Worldcon, bringing together the best elements of numerous Young Friends must be born on or after 14 August different SF and fannish traditions, and reaching 1988. out to new fans from all around the world. Photo by Maurice.as seen at http://www.flickr.com/photos/mauricedb The 70<h World Science Fiction Convention CHICON 7 August 30 — September 3, 2012 Chicago, Illinois Author Guest of Honor MIKE RESNICK Fan Guest of Honor PEGGY RAE SAPIENZA Artist Guest of Honor ROWENA MORRILL Agent Guest of Honor JANE FRANK Astronaut Guest of Honor STORY MFSGRAVE Toastmaster JOHN SCALZI Special Guest SY LIERERGOT PROGRESS REPORT 4 http://chicon.org © 201 I "Chicago Worldcon Bid”, B/IB/A Chiron 7. “World Science Fiction Society”. “WSFS”, “World Science Fiction Convention”, “Worldcon”, “NASFiC”, “lingo Award”, and the distinctive design of the lingo Award Rocket arc service marks of the World Science Fiction Society, an unincorporated literary society. -

Letter from the Chair Symposium Committee

Letter from the Chair Hello and welcome to another year of LTUE! Every year While I am the head of this year’s event, I am only one at LTUE, we strive to bring you an amazing experience of of many, many people who make this possible each year. learning about creating science fiction and fantasy, and I I would first like to thank our panelists. You are the ones am excited to be presenting to you this year’s rendition! who come and share your knowledge and insights with us. We as a committee have been working hard all year to Without you there would be no symposium, no point in our make it an excellent symposium for you, and I hope coming! Second, I would like to profusely thank our com- that you find something (or many somethings) that you mittee members and volunteers. You are the ones who put enjoy. If you are new to the symposium, welcome and everything together throughout the year and make things come discover something amazing! If you are returning, run smoothly through our three intense days together. welcome back and I hope you build on what you learned Third, I would like to thank all of our attendees. You are in the past. why we all do the work to create this amazing symposium! For me, LTUE has been a great land of discovery. I have Enjoy your time here, whatever your role may be. Find learned how to do many things. I have learned about something to take with you when you leave, and try to myself as a creator. -

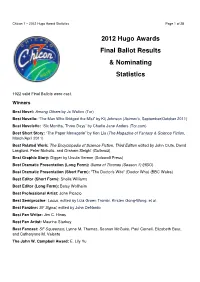

2012 Hugo Awards Final Ballot Results & Nominating Statistics

Chicon 7 – 2012 Hugo Award Statistics Page 1 of 28 2012 Hugo Awards Final Ballot Results & Nominating Statistics 1922 valid Final Ballots were cast. Winners Best Novel: Among Others by Jo Walton (Tor) Best Novella: “The Man Who Bridged the Mist” by Kij Johnson ( Asimov's , September/October 2011) Best Novelette: “Six Months, Three Days” by Charlie Jane Anders (Tor.com) Best Short Story: “The Paper Menagerie” by Ken Liu ( The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction , March/April 2011) Best Related Work: The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Third Edition edited by John Clute, David Langford, Peter Nicholls, and Graham Sleight (Gollancz) Best Graphic Story: Digger by Ursula Vernon (Sofawolf Press) Best Dramatic Presentation (Long Form): Game of Thrones (Season 1) (HBO) Best Dramatic Presentation (Short Form): "The Doctor's Wife" (Doctor Who) (BBC Wales) Best Editor (Short Form): Sheila Williams Best Editor (Long Form): Betsy Wollheim Best Professional Artist: John Picacio Best Semiprozine : Locus, edited by Liza Groen Trombi, Kirsten Gong-Wong, et al. Best Fanzine: SF Signal , edited by John DeNardo Best Fan Writer: Jim C. Hines Best Fan Artist: Maurine Starkey Best Fancast: SF Squeecast , Lynne M. Thomas, Seanan McGuire, Paul Cornell, Elizabeth Bear, and Catherynne M. Valente The John W. Campbell Award: E. Lily Yu Chicon 7 – 2012 Hugo Award Statistics Page 2 of 28 Best Novel – 1664 ballots counted First Place Among Others ( WINNER ) 421 424 493 585 769 Embassytown 324 324 392 492 608 Deadline 311 312 367 418 A Dance With Dragons 316 317 360 -

A Fun Month. Oasfis Was Represented at the UCF Bookfair. the Picnic

Volume 24 Number 12 Issue 294 May 2012 A WORD FROM THE EDITOR The 2012 Hugo and John W. Campbell Award Nominees A fun month. OASFiS was represented at the (source Chicon 7 website) UCF Bookfair. The picnic was great. Thank You 1101 valid nominating ballots were received and counted. Susan Cole and Bonny Bealle and everyone who Best Novel (932 ballots) helped out. The Hugo Nominees were announced Among Others by Jo Walton (Tor) online on April 7. There are a lot of great nominees. A Dance With Dragons by George R. R. Martin (Bantam Spectra) Deadline by Mira Grant (Orbit) Next month we will have the Nebula winners, Embassytown by China Miéville (Macmillan / Del Rey) some pictures from OASIS and a review or 2. Leviathan Wakes by James S. A. Corey (Orbit) Till next time. Best Novella (473 ballots) Countdown by Mira Grant (Orbit) . “The Ice Owl” by Carolyn Ives Gilman (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, November/December 2011) “Kiss Me Twice” by Mary Robinette Kowal (Asimov's, June 2011) “The Man Who Bridged the Mist” by Kij Johnson (Asimov's, September/October 2011) “The Man Who Ended History: A Documentary” by Ken Liu (Panverse 3) Silently and Very Fast by Catherynne M. Valente (Clarkesworld / WSFA) Best Novelette (499 ballots) Leviathan Wakes “The Copenhagen Interpretation” by Paul Cornell (Asimov's, July by 2011) James A. Corey “Fields of Gold” by Rachel Swirsky (Eclipse Four) (Daniel Abraham & Ty Franck) “Ray of Light” by Brad R. Torgersen (Analog, December 2011) The Human population is expanding in the Solar “Six Months, Three Days” by Charlie Jane Anders (Tor.com) System. -

In Memory of Ken Hunt December 25, 1955-August 20, 2012 Chicon 7 Head of Logistics Contents

In Memory of Ken Hunt December 25, 1955-August 20, 2012 Chicon 7 Head of Logistics Contents Welcome . 4 Opening Ceremonies . 15 Information First Night at the Adler Yes, You Do Need Planetarium . 15 Your Badge! . 5 Masquerade Registration . 15 Badges . 5 Neil Gaiman Theatre . 15 Lost Badges . 5 Regency Dancing . 16 Lost and Found . 5 Moebius Theatre . 16 Weapons Policy . 5 Geek Prom . 16 Cubs Tickets . 6 Masquerade . 16 Childcare . 6 The Hugo Awards Alcohol Policy . 7 Ceremony . 16 Code of Conduct . 7 Closing Ceremonies . 16 Gophers . 7 Stroll With the Stars . 17 Chicon 7 Souvenirs . 7 Awards Information Desks . 8 Seiun Awards Ceremony . 17 Disability Services . 8 Libertarian Futurist Society Fire Sale . 8 Prometheus Award Voodoo Boards . 8 Ceremony . 17 Hotel Information Chesley Awards Hyatt . 9 Ceremony . 17 Parking . 9 Sidewise Awards Parties General Rules . 9 Ceremony . 17 Pets . 9 The Carl Brandon Society Pool . 9 Awards Ceremony . 17 Refrigerators . 10 The Golden Duck Awards 18 Packages and Letters . 10 Programming Taxes . 10 Academic Programming . 18 Telephone . 10 Science Fiction for Educators Cell Phone Reception . 10 (Teaching SF) . 18 Wi-Fi . 10 Autographing . 18 Near the Hyatt . 10 Writer Under Glass . 18 Hotel Information: Kaffeeklatsches and Sheraton . 11 Literary Bheers . 19 Facilities 1632 . 19 Con Suite . 11 Dragon*Con . 19 Concourse . 11 Anime and Cartoons . 20 Fan Tables . 12 Chicon 7 Independent Haggard Room . 12 Film Festival . 20 The Fan Lounge . 12 ChiKidz . 20 Art Show . 12 Program Schedule Art Show Docent Tours . 12 Thursday . 22 Art Auction . 13 Friday . 34 Chesley Art Award . 13 Saturday . 56 Dealers’ Room . -

Asfacts Apr12.Pub

ASFACTS 2012 APRIL “L ET IT RAIN ” S PRING ISSUE Fiction, Third Edition edited by John Clute, David Lang- ford, Peter Nicholls & Graham Sleight, Jar Jar Binks Must Die… and Other Observations about Science Fic- tion Movies by Daniel M. Kimmel, Wicked Girls by Se- anan McGuire, WRITING EXCUSES , S EASON 6 BY BRAN- DON SANDERSON , Dan Wells, Howard Tayler, Mary Robinette Kowal, & Jordan Sanderson, and The Steam- UTHORS UBONICON RIENDS punk Bible by Jeff VanderMeer & S.J. Chambers. NM A & B F GRAPHIC STORY: The Unwritten, Vol. 2: Leviathan AMONG 2012 H UGO NOMINEES by Mike Carey, Locke & Key, Vol. 4: Keys To The King- dom by Joe Hill, Schlock Mercenary: Force Multiplica- Nominees for the Hugo Awards and for the John tion by Howard Tayler, DIGGER BY URSULA VERNON , W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer were an- and Fables, Vol. 15: Rose Red by Bill Willingham & nounced the first weekend of April at Eastercon by Chi- Mark Buckingham. con 7. Among the nominees are three NM authors for DRAMATIC PRESENTATION – LONG: Captain best novel (and George RR Martin’s HBO series of America: The First Avenger, GAME OF THRONES : S EASON Game of Thrones for dramatic presentation). Of other 1, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2, Hugo interest are nominations for 2011 visitors to Albuquer- and Source Code . DRAMATIC PRESENTATION – que – Catherynne M. Valente, Paul Cornell and John SHORT: Community : “Remedial Chaos Theory,” “The Picacio – and Bubonicon 44 guests Brandon Sanderson Drink Tank’s Hugo Acceptance Speech,” Doctor Who : and Ursula Vernon. The 70th World Science Fiction “The Doctor’s Wife,” Doctor Who : “The Girl Who Convention will be held in Chicago, Ill, August 30- Waited,” and Doctor Who : “A Good Man Goes to War.” September 3, 2012. -

The 26Th Annual Readers' Award Results

EDITORIAL Sheila Williams TWENTY-SIXTH ANNUAL READERS’ AWARDS RESULTS On May 19, we treated our Twenty-Sixth Connie Willis, her husband Courtney, Annual Readers’ Award winners to a and their daughter, Cordelia, have often breakfast celebration at the Hyatt Re- been invited to our Readers’ Awards gency Crystal City’s lovely Cinnabar breakfast because of Connie’s long associ- Restaurant in Arlington, Virginia. As usu- ation with the magazine. Over the years, al, our ceremony was held in conjunction her Asimov’s stories have been recipients with the Science Fiction and Fantasy of four of her seven Nebulas and nine of Writer’s Nebula Awards Weekend. We her eleven Hugos. This year, the family were pleased that this meant a number attended our breakfast because Connie’s of our winners were on hand to accept delightful tale “All About Emily” was the their awards in person. winner of our Readers’ Award for best In addition to winning the short story novelette. Later that evening at the Neb- award for her beautiful tale of “Move- ula reception, she became the newest of ment,” Nancy Fulda also qualified for SFWA’s Grand Masters. We are proud the award for furthest distance traveled. that we’ve been, and continue to be, a part Nancy had flown in from her home in of this brilliant author’s storied career. Germany. She was met in DC by her Due to a family commitment, Kij John- charming sister, Sandra Tayler, who’d son couldn’t attend our breakfast or the just arrived from Utah. The women told Nebula weekend. -

2012 Hugo Awards Final Ballot and John W

The 7Dth World Science Fiction Convention Aug, 3O-SEPT. 3, 2012 WWW.CHICDN.DRG HUGO AWARD" 2012 Hugo Awards Final Ballot and John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer All ballots must be received by Tuesday, July 31, 20.12, 11:59 pm PDT. Eligibility to Vote All Attending, Young Adult, and Supporting members of Chicon 7 are eligible to vote. Vote Online Vote by Mail Online voting is available via the Chicon 7 website: To vote by mail, please complete the membership information below. Paper ballots may be mailed to: https://chicon.oig/hugo-awaids.php HUGO NOMINATIONS If you are currently a member of Chicon 7 you will need your C/0 JEFF ORTH Personal Identification Number (PIN), printed on the mailing label 8813 VIRGINIA LANE of this progress report, to vote via the web. You may also email KANSAS CITY, MO 61111 USA [email protected] to gel your PIN. Please mail your ballot in a secure envelope. Do not fold or staple Online ballots may be revised before the deadline by submilling a your ballot. All ballots must arrive by the deadline. new ballot. Only the latest ballot received is counted. If you have any questions please email us at [email protected] Membership Membership Purchase ___ I am a member of Chicon 7. Please complete the following to purchase a membership. ___ 1 want to purchase a membership. Rates below are valid until ___Attending $215 USD July 31,2012. Membership Information (required) ___ Young Adult (age 17-21 years on August 30, 2012) $100 USD Please complete the following before submitting your ballot. -

Philosophers' Science Fiction / Speculative Fiction

Philosophers’ Science Fiction / Speculative Fiction Recommendations, Organized by Author / Director August 15, 2016 Eric Schwitzgebel Since September 2014, I have been gathering recommendations of “philosophically interesting” science fiction – or “speculative fiction” (SF), more broadly construed – from professional philosophers. So far, 48 philosophers have contributed (plus one co-contributor). Each contributor has recommended ten works of speculative fiction and has written a brief “pitch” gesturing toward the interest of the work. Below is the list of recommendations, arranged to highlight the authors and film directors or TV shows who were most often recommended by the list contributors. I have divided the list into (A.) novels, short stories, and other printed media, vs (B.) movies, TV shows, and other non- printed media. Within each category, works are listed by author or director/show, in order of how many different contributors recommended that author or director, and then by chronological order of works for authors and directors/shows with multiple listed works. For works recommended more than once, I have included each contributor’s pitch on a separate line. The most recommended authors were: Recommended by 13 contributors: Ursula K. Le Guin Recommended by 11: Ted Chiang Philip K. Dick Recommended by 8: Greg Egan Stanisław Lem Recommended by 7: Isaac Asimov Recommended by 6: Margaret Atwood Octavia Butler Recommended by 5: Edwin Abbot Robert A. Heinlein Kazuo Ishiguro China Miéville Neal Stephenson Kurt Vonnegut Recommended by 4: Douglas Adams R. Scott Bakker Jorge Luis Borges Ray Bradbury David Brin P. D. James Charles Stross Gene Wolfe Recommended by 3: Iain M. Banks Italo Calvino Orson Scott Card Arthur C.