Perceptions of Stanford's Piano Music Adèle Commins, Dundalk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst La Ttéiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’S Preludes for Piano Op.163 and Op.179: a Musicological Retrospective

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst la ttÉiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’s Preludes for Piano op.163 and op.179: A Musicological Retrospective (3 Volumes) Volume 1 Adèle Commins Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare 2012 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisors: Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley & Dr Patrick F. Devine Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to a number of people who have helped me throughout my doctoral studies. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors and mentors, Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Dr Patrick Devine, for their guidance, insight, advice, criticism and commitment over the course of my doctoral studies. They enabled me to develop my ideas and bring the project to completion. I am grateful to Professor Fiona Palmer and to Professor Gerard Gillen who encouraged and supported my studies during both my undergraduate and postgraduate studies in the Music Department at NUI Maynooth. It was Professor Gillen who introduced me to Stanford and his music, and for this, I am very grateful. I am grateful to the staff in many libraries and archives for assisting me with my many queries and furnishing me with research materials. In particular, the Stanford Collection at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University has been an invaluable resource during this research project and I would like to thank Melanie Wood, Elaine Archbold and Alan Callender and all the staff at the Robinson Library, for all of their help and for granting me access to the vast Stanford collection. -

Reception of Charles Villiers Stanford and His Music in the American Press Dr Adèle Commins, Auteur(S) Dundalk Institute of Technology, Ireland

Watchmen on the Walls of Music Across the Atlantic: Reception of Charles Villiers Stanford and his Music in the American Press Dr Adèle Commins, Auteur(s) Dundalk Institute of Technology, Ireland Titre de la revue Imaginaires (ISSN 1270-931X) 22 (2019) : « How Popular Culture Travels: Cultural Numéro Exchanges between Ireland and the United States » Pages 29-59 Directeur(s) Sylvie Mikowski et Yann Philippe du numéro DOI de l’article 10.34929/imaginaires.vi22.5 DOI du numéro 10.34929/imaginaires.vi22 Ce document est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons attribution / pas d'utilisation commerciale / pas de modification 4.0 international Éditions et presses universitaires de Reims, 2019 Bibliothèque Robert de Sorbon, Campus Croix-Rouge Avenue François-Mauriac, CS 40019, 51726 Reims Cedex www.univ-reims.fr/epure Watchmen on the Walls of Music Across the Atlantic: Reception of Charles Villiers Stanford and How PopularHow Culture Travels his Music in the American Press #22 IMAGINAIRES Dr Adèle Commins Dundalk Institute of Technology, Ireland Introduction Irish born composer Charles Villiers Stanford (1852–1924) is a cen- tral figure in the British Musical Renaissance. Often considered only in the context of his work in England, with occasional references to his Irish birthplace, the reception of Stanford’s music in America provides fresh perspectives on the composer and his music. Such a study also highlights the circulation of culture between Ireland, England and the USA at the start of the twentieth century and the importance of national identity in a cosmopolitan society of many diasporas. Although he never visited America, the reception of Stanford’s music and reviews in the American media highlight the cultural (mis)understanding that existed and the evolving identities in both American and British society at the turn of the twentieth century. -

Eloquence Releases: Summer 2017 by Brian Wilson

Some Recent Eloquence Releases: Summer 2017 by Brian Wilson The original European Universal Eloquence label replaced budget releases on DG (Privilege or Resonance), Decca (Weekend Classics) and Philips (Classical Favourites). Like them it originally sold for around £5 and offered some splendid bargains such as Telemann’s ‘Water Music’ and excerpts from Tafelmusik (Musica Antiqua Köln/Reinhard Goebel 4696642) and Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde (Janet Baker, James King, Concertgebouw/Bernard Haitink 4681822). Later most of the original batch were deleted – luckily the Mahler remains available – and production switched to Universal Australia but the price remained around the same. More recently changes in the value of the £ mean that single CDs now sell for around £7.75 but the high quality of much of the repertoire means that they remain well worth keeping an eye on. Many, but not all, of the albums are available to stream or download and I have reviewed some in that form and others on CD. Be aware, however, that the downloads often cost more than the CDs and invariably come without notes – which is a shame because the Eloquence booklets are better than those of many budget labels. THE TUDORS Lo, Country Sports Anonymous Almain Thomas TOMKINS Adieu, Ye City-Prisoning Towers Thomas WEELKES Lo, Country Sports that Seldom Fades Nicholas BRETON Shepherd and Shepherdess Michael EAST Sweet Muses, Nymphs and Shepherds Sporting Bar YOUNG The Shepherd, Arsilius’s, Reply John FARMER O Stay, Sweet Love Giles FARNABY Pearce did love fair Petronel Michael -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

An Annotated Catalogue of the Major Piano Works of Sergei Rachmaninoff Angela Glover

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 An Annotated Catalogue of the Major Piano Works of Sergei Rachmaninoff Angela Glover Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC AN ANNOTATED CATALOGUE OF THE MAJOR PIANO WORKS OF SERGEI RACHMANINOFF By ANGELA GLOVER A Treatise submitted to the School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2003 The members of the Committee approve the treatise of Angela Glover defended on April 8, 2003. ___________________________________ Professor James Streem Professor Directing Treatise ___________________________________ Professor Janice Harsanyi Outside Committee Member ___________________________________ Professor Carolyn Bridger Committee Member ___________________________________ Professor Thomas Wright Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract………………………………………………….............................................. iv INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………. 1 1. MORCEAUX DE FANTAISIE, OP.3…………………………………………….. 3 2. MOMENTS MUSICAUX, OP.16……………………………………………….... 10 3. PRELUDES……………………………………………………………………….. 17 4. ETUDES-TABLEAUX…………………………………………………………… 36 5. SONATAS………………………………………………………………………… 51 6. VARIATIONS…………………………………………………………………….. 58 BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………………. -

Proquest Dissertations

The use of the glissando in piano solo and concerto compositions from Domenico Scarlatti to George Crumb Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Lin, Shuennchin Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 08:04:22 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/288715 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI fihns the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fice, whfle others may be from any type of computer primer. The qaality^ of this rqirodnctioii is dependent upon the quality of the copy sabmitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and hnproper alignmem can adverse^ affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., nu^s, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^inning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing fi'om left to right m equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Charles Villiers Stanford's Experiences with and Contributions

Charles Villiers Stanford’s Experiences with and contributions to the solo piano repertoire Adèle Commins Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) has long been considered as one of the leaders of the English Musical Renaissance on account of his work as composer, conductor and pedagogue. In his earlier years he rose to fame as a piano soloist, having been introduced to the instrument at a very young age. It is no surprise then that his first attempts at composition included a march for piano in i860.1 The piano continued to play an important role in Stanford’s compositional career and his last piano work, Three Fancies, is dated 1923. With over thirty works for the instrument, not counting his piano duets, Stanford’s piano pieces can be broadly placed in three categories: (i) piano miniatures or character pieces which are in the tradition of salon or domestic music; (ii) works which have a pedagogical function; and (iii) works which are written in a more virtuosic vein. In each of these categories many of the works remain unpublished. In most cases the piano scores are not available for purchase and this has hindered performances after his death.2 The repertoire of pianists should not be limited to the music of European composers and publishers, like performers, are responsible for the exposure a composer’s works receives. New editions of Stanford’s piano music need to be created and published in order to raise awareness of the richness of Stanford’s contribution to piano literature. While there has been renewed interest in the composer’s life and music by musicologists and performers — primarily initiated by the recent Stanford biographies in 2002 by Dibble and Rodmell — the 1 Originally termed Opus 1 in Stanford’s sketch book it was reproduced in Anon., ‘Charles Villiers Stanford’, The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, 39 670 (1898), 785-793 (p. -

Brookland Road Poem by Rudyard Kipling

1 Brookland road Poem by Rudyard Kipling Song for Solo Voice & Piano by H. Walford Davies VOCAL SCORE 2 This score is in the Public Domain and has No Copyright under United States law. Anyone is welcome to make use of it for any purpose. Decorative images on this score are also in the Public Domain and have No Copyright under United States law. No determination was made as to the copyright status of these materials under the copyright laws of other countries. They may not be in the Public Domain under the laws of other countries. EHMS makes no warranties about the materials and cannot guarantee the accuracy of this Rights Statement. You may need to obtain other permissions for your intended use. For example, other rights such as publicity, privacy or moral rights may limit how you may use the material. You are responsible for your own use. http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/NoC-US/1.0/ Text written for this score, including project information and descriptions of individual works does have a new copyright, but is shared for public reuse under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0 International) license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Cover Image: “The Vale of Dedham” by John Constable, 1828 3 The “renaissance” in English music is generally agreed to have started in the late Victorian period, beginning roughly in 1880. Public demand for major works in support of the annual choral festivals held throughout England at that time was considerable which led to the creation of many large scale works for orchestra with soloists and chorus. -

The First Piano Concerto of Johannes Brahms: Its History and Performance Practice

THE FIRST PIANO CONCERTO OF JOHANNES BRAHMS: ITS HISTORY AND PERFORMANCE PRACTICE A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS by Mark Livshits Diploma Date August 2017 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Joyce Lindorff, Advisory Chair, Keyboard Studies Dr. Charles Abramovic, Keyboard Studies Dr. Michael Klein, Music Studies Dr. Maurice Wright, External Member, Temple University, Music Studies ABSTRACT In recent years, Brahms’s music has begun to occupy a larger role in the consciousness of musicologists, and with this surge of interest came a refreshingly original approach to his music. Although the First Piano Concerto op. 15 of Johannes Brahms is a beloved part of the standard piano repertoire, there is a curious under- representation of the work through the lens of historical performance practice. This monograph addresses the various aspects that comprise a thorough performance practice analysis of the concerto. These include pedaling, articulation, phrasing, and questions of tempo, an element that takes on greater importance beyond just complicating matters technically. These elements are then put into the context of Brahms’s own pianism, conducting, teaching, and musicological endeavors based on first and second-hand accounts of the composer’s work. It is the combining of these concepts that serves to illuminate the concerto in a far more detailed fashion, and ultimately enabling us to re-evaluate whether the time honored modern interpretations of the work fall within the boundaries that Brahms himself would have considered effective and accurate. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to my committee and Dr. -

2020.12.04 Opera Theater Program

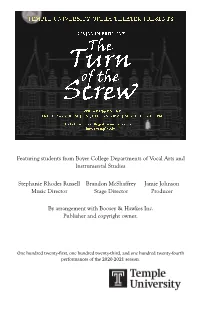

The Touf trhen Screw Featuring students from Boyer College Departments of Vocal Arts and Instrumental Studies Stephanie Rhodes Russell Brandon McShaffrey Jamie Johnson Music Director Stage Director Producer By arrangement with Boosey & Hawkes Inc. Publisher and copyright owner. One hundred twenty-first, one hundred twenty-third, and one hundred twenty-fourth performances of the 2020-2021 season. Cast Prologue/Quint .........................................................................................Hayden Smith (Cover: Gabriel Feldt) Governess ................................................................................................Marta Zaliznyak (Cover: Rebecca Lundy) Miles ......................................................................................................Alexis Lapreziosa (Cover: Yaqi Yang) Flora................................................................................................................ Katie Hahn (Cover: Gretchen Enterline) Mrs. Grose ...........................................................................................Marcelyn Lebovitz (Cover: Jiaying Liu) Miss Jessel ...............................................................................................Patricia Luecken Orchestra VIOLIN I FLUTE/PICCOLO/ALTO FLUTE Yuan Tian Hyerin Kim VIOLIN II OBOE/ENGLISH HORN Jason Zi Wang Geoffrey Deemer VIOLA CLARINET/BASS CLARINET Brooke Mead Wendy Bickford CELLO BASSOON Harris Banks Joshua Schairer DOUBLE BASS HORN William Valencia Tapia Lucy Smith HARP Katherine Ventura PERCUSSION -

Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Masters Applied Arts 2018 Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930. David Scott Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appamas Part of the Composition Commons Recommended Citation Scott, D. (2018) Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930.. Masters thesis, DIT, 2018. This Theses, Masters is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900–1930 David Scott, B.Mus. Thesis submitted for the award of M.Phil. to the Dublin Institute of Technology College of Arts and Tourism Supervisor: Dr Mark Fitzgerald Dublin Institute of Technology Conservatory of Music and Drama February 2018 i ABSTRACT Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, arrangements of Irish airs were popularly performed in Victorian drawing rooms and concert venues in both London and Dublin, the most notable publications being Thomas Moore’s collections of Irish Melodies with harmonisations by John Stephenson. Performances of Irish ballads remained popular with English audiences but the publication of Stanford’s song collection An Irish Idyll in Six Miniatures in 1901 by Boosey and Hawkes in London marks a shift to a different type of Irish song.