NASA's Scientist-Astronauts David J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Man High Commemoration

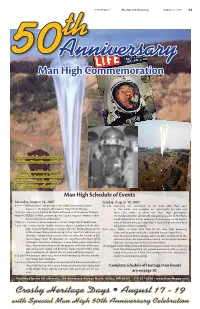

NewsHopperTM Man High 50th Anniversary August 11, 2007 13 th 50Anniversary Man High Commemoration Please thank the advertisers for making this section possible. And a special thank you to Beverly Mindrum Johnson and the Cuyuna Country Heritage Preservation Society. Man High Schedule of Events Saturday, August 18, 2007 Sunday, August 19, 2007 9 a.m.— “Defeating Pain” symposium at The Hallett Community Center. 10 a.m.—Gathering and ceremonies at the Croft Mine Park open Session 1—Dr. Simons will speak on Trigger Point Therapy. to the public and providing an opportunity for area resi- 10:30 a.m.—Session 1—Carolyn McMakin will speak on Microcurrent Therapy. dents and other to meet the Man High participants. Noon—CATERED LUNCH provided by the Cuyuna Regional Medical Center. The Sunday schedule will include transporting guests to the Ports- Post-session informal discussion. mouth Overlook for a short ceremony. At that ceremony the Depart- 1:30 p.m.—Caravan to space presentation at the C-I High School Auditorium. ment of Natural Resources Man High II Kiosk will be unveiled. Band 2 p.m.—Dr. Simons, former Apollo Astronaut Duane Graveline and Dr. Mar- will perform military numbers. cello Vasquez, NASA liaison scientist with the Medical Department 10:45 a.m.— Return to Croft Mine Park for the Man High Ceremony. of Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, New York, will present a Colors will be presented by the Crosby and Ironton Legion Posts; three-part symposium on cosmic radiation and other hazards to hu- Carla Gutzman & Kris Hasskamp, solists; speakers will include Dr. -

Is the Brain-Mind Quantum? a Theoretical Proposal with Supporting Evidence

IS THE BRAIN-MIND QUANTUM? A THEORETICAL PROPOSAL WITH SUPPORTING EVIDENCE Stuart Kauffmana and Dean Radinb a Emeritus Professor of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] b Chief Scientist, Institute of Noetic Sciences, Petaluma, CA; , Associated Distinguished Professor, California Institute of Integral Studies, San Francisco, CA, USA [email protected]. ORCID: 0000-0003-0041-322X Abstract If all aspects of the mind-brain relationship were adequately explained by classical physics, then there would be no need to propose alternative views. But faced with possibly unresolvable puzzles like qualia and free will, other approaches are required. We propose a non-substance dualism theory, following a suggestion by Heisenberg, whereby the world consists of both ontologically real Possibles that do not obey Aristotle’s law of the excluded middle, and ontologically real Actuals, that do obey the law of the excluded middle. Measurement converts Possibles into Actuals. This quantum-oriented approach solves numerous puzzles about the mind-brain relationship, but it also raises the intriguing possibility that some aspects of mind are nonlocal, and that mind plays an active role in the physical world. We suggest that the mind-brain relationship is partially quantum, and we present evidence supporting that proposition. Keywords: brain-mind, quantum biology, consciousness, quantum measurement 1. Introduction Of the three central mysteries in science, the Origin of the Universe, the Origin of Life, and the Origin of Consciousness, the last is the most challenging. As philosopher Jerry Fodor put it in 1992, “Nobody has the slightest idea how anything material could be conscious. Nobody even knows what it would be like to have the slightest idea about how anything could be conscious” [1]. -

How Much Have We Advanced?

English How much have Pedagogical Module 2 we advanced? Curricular Threads: Communication and Cultural Awareness, Oral Communication, Reading, Writing, Language Through the Arts First Course BGU Past perfect 5 Scientific inventions and Science 6 their impact on humanity Present perfect 4 Social Studies History of 7 inventions Simple past 3 Language Analyzing short Past and present English Technology 8 non-fiction pieces perfect expressions 2 and Beyond Vocabulary about technology and 1 inventions Values Importance Healthcare 10 9 of immunization Incredible Inventions Have you ever imagined a world without we have created powerful devices that allow cars or television? Imagine waiting for months us see the vast universe. to hear from your loved ones. Imagine getting sick and having no medicine. We are going Nowadays it is possible to video chat with to travel through history and observe human’s anyone anywhere for free. We have access infinite curiosity and inventions that have to infinite amounts of information and we can post changed the world. Discover creations that our own thoughts and opinions. Technology have shaped culture and lifestyle. Our brains has developed a lot during the last hundred years have even taken our people to the moon and and will continue to develop in the future. What positive and negative impacts have human inventions had? Non-Commercial Licence Non-Commercial 1 Lesson A Communication and Cultural Awareness Social Studies How have humans’ creations changed the world? Discoveries from Ancient Cultures Interesting Facts Believe it or not, people that lived many years ago invented things that are still used nowadays. -

Nasa Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Oral History 5 Transcript

NASA JOHNSON SPACE CENTER ORAL HISTORY PROJECT ORAL HISTORY 5 TRANSCRIPT JOSEPH P. ALLEN INTERVIEWED BY JENNIFER ROSS-NAZZAL MCLEAN, VIRGINIA – 18 APRIL 2006 The questions in this transcript were asked during an oral history session with Dr. Joseph P. Allen Dr. Allen has amended the answers for clarification purposes. As a result, this transcript does not exactly match the audio recording th ROSS-NAZZAL: Today is April 18 , 2006. This oral history with Joseph P. Allen is being conducted for the Johnson Space Center Oral History Project in McLean, Virginia. Jennifer Ross-Nazzal is the interviewer. Thanks again for joining me for our fifth session. ALLEN: Thank you, Jennifer, thank you. Is today the hundredth anniversary of the San Francisco earthquake? ROSS-NAZZAL: I think so, yes. ALLEN: A very interesting day today. ROSS-NAZZAL: I wanted to start, actually, by going back and asking you about something we should have talked about in your first interview, and that’s astronaut desert survival training in Washington that you participated in in 1967. ALLEN: Ah, yes. Well, I do have some recollection of it, and it’s just one of several survival schools that the early astronaut training had us go to. If memory serves me, one was water 18 April 2006 1 Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Joseph P. Allen survival, another was jungle survival, and then there was desert survival. I believe the desert survival may have been the first. The way NASA does that, of course, is they outsource it. They hire the military to provide military training, because the military runs survival schools on a very regular basis. -

Story Musgrave (M.D.) Nasa Astronaut (Former)

Biographical Data Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas 77058 National Aeronautics and Space Administration STORY MUSGRAVE (M.D.) NASA ASTRONAUT (FORMER) PERSONAL DATA: Born August 19, 1935, in Boston, Massachusetts, but considers Lexington, Kentucky, to be his hometown. Single. Six children (one deceased). His hobbies are chess, flying, gardening, literary criticism, microcomputers, parachuting, photography, reading, running, scuba diving, and soaring. EDUCATION: Graduated from St. Mark’s School, Southborough, Massachusetts, in 1953; received a bachelor of science degree in mathematics and statistics from Syracuse University in 1958, a master of business administration degree in operations analysis and computer programming from the University of California at Los Angeles in 1959, a bachelor of arts degree in chemistry from Marietta College in 1960, a doctorate in medicine from Columbia University in 1964, a master of science in physiology and biophysics from the University of Kentucky in 1966, and a master of arts in literature from the University of Houston in 1987. ORGANIZATIONS: Member of Alpha Kappa Psi, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Beta Gamma Sigma, the Civil Aviation Medical Association, the Flying Physicians Association, the International Academy of Astronautics, the Marine Corps Aviation Association, the National Aeronautic Association, the National Aerospace Education Council, the National Geographic Society, the Navy League, the New York Academy of Sciences, Omicron Delta Kappa, Phi Delta Theta, the Soaring Club of Houston, the Soaring Society of America, and the United States Parachute Association. SPECIAL HONORS: National Defense Service Medal and an Outstanding Unit Citation as a member of the United States Marine Corps Squadron VMA-212 (1954); United States Air Force Post-doctoral Fellowship (1965-1966); National Heart Institute Post-doctoral Fellowship (1966-1967); Reese Air Force Base Commander’s Trophy (1969); American College of Surgeons I.S. -

SEAFARING WOMEN: an Investigation of Material Culture for Potential Archaeological Diagnostics of Women on Nineteenth-Century Sailing Ships

SEAFARING WOMEN: An Investigation of Material Culture for Potential Archaeological Diagnostics of Women on Nineteenth-Century Sailing Ships by R. Laurel Seaborn April, 2014 Director of Thesis/Dissertation: Dr. Lynn Harris Major Department: Department of History, Program in Maritime Studies ABSTRACT During the 19th century, women went to sea on sailing ships. Wives and family accompanied captains on their voyages from New England. They wrote journals and letters that detailed their life on board, adventures in foreign ports, and feelings of separation from family left behind. Although the women kept separate from the sailors as class and social status dictated, they contributed as nannies, nurses and navigators when required. Examination of the historical documents, ship cabin plans, and photos of those interiors, as well as looking at surviving ships, such as the whaleship Charles W. Morgan, provided evidence of the objects women brought and used on board. The investigation from a gendered perspective of the extant material culture, and shipwreck site reports laid the groundwork for finding potential archaeological diagnostics of women living on board. SEAFARING WOMEN: An Investigation of Material Culture for Potential Archaeological Diagnostics of Women on Nineteenth-Century Sailing Ships A Thesis/Dissertation Presented To the Faculty of the Department of Department Name Here East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by R. Laurel Seaborn April, 2014 © R. Laurel Seaborn, 2014 SEAFARING WOMEN: An Investigation of Material Culture for Potential Archaeological Diagnostics of Women on Nineteenth-Century Sailing Ships by R. Laurel Seaborn APPROVED BY: DIRECTOR OF THESIS:_________________________________________________________ Dr. -

NASA History Fact Sheet

NASA History Fact Sheet National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of Policy and Plans NASA History Office NASA History Fact Sheet A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION by Stephen J. Garber and Roger D. Launius Launching NASA "An Act to provide for research into the problems of flight within and outside the Earth's atmosphere, and for other purposes." With this simple preamble, the Congress and the President of the United States created the national Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) on October 1, 1958. NASA's birth was directly related to the pressures of national defense. After World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union were engaged in the Cold War, a broad contest over the ideologies and allegiances of the nonaligned nations. During this period, space exploration emerged as a major area of contest and became known as the space race. During the late 1940s, the Department of Defense pursued research and rocketry and upper atmospheric sciences as a means of assuring American leadership in technology. A major step forward came when President Dwight D. Eisenhower approved a plan to orbit a scientific satellite as part of the International Geophysical Year (IGY) for the period, July 1, 1957 to December 31, 1958, a cooperative effort to gather scientific data about the Earth. The Soviet Union quickly followed suit, announcing plans to orbit its own satellite. The Naval Research Laboratory's Project Vanguard was chosen on 9 September 1955 to support the IGY effort, largely because it did not interfere with high-priority ballistic missile development programs. -

Human Spaceflight. Activities for the Primary Student. Aerospace Education Services Project

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 288 714 SE 048 726 AUTHOR Hartsfield, John W.; Hartsfield, Kendra J. TITLE Human Spaceflight. Activities for the Primary Student. Aerospace Education Services Project. INSTITUTION National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Cleveland, Ohio. Lewis Research Center. PUB DATE Oct 85 NOTE 126p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Materials (For Learner) (051) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Aerospace Education; Aerospace Technology; Educational Games; Elementary Education; *Elementary School Science; 'Science Activities; Science and Society; Science Education; *Science History; *Science Instruction; *Space Exploration; Space Sciences IDENTIFIERS *Space Travel ABSTRACT Since its beginning, the space program has caught the attention of young people. This space science activity booklet was designed to provide information and learning activities for students in elementary grades. It contains chapters on:(1) primitive beliefs about flight; (2) early fantasies of flight; (3) the United States human spaceflight programs; (4) a history of human spaceflight activity; (5) life support systems for the astronaut; (6) food for human spaceflight; (7) clothing for spaceflight and activity; (8) warte management systems; (9) a human space flight le;g; and (10) addition 1 activities and pictures. Also included is a bibliography of books, other publications and films, and the answers to the three word puzzles appearing in the booklet. (TW) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** HUMAN SPACEFLIGHT U.S DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION Activities CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproduced as mewed from the person or organization originating it Minor changes have been made to norm. -

The Dorothy Hodgkin Symposium

The Principal and Fellows of Somerville College, Oxford together with UNESCO and the International Union of Crystallography request the pleasure of your company at The Dorothy Hodgkin Symposium Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the award of Dorothy Hodgkin’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry and the International Year of Crystallography Wednesday 29th October 2014 You are warmly invited to attend a one-day symposium that aims to recognise Dorothy Hodgkin’s legacy and mark the award of her Nobel Prize. Her field, crystallography, underpins all of the sciences today and has an extensive range of applications within the agro-food, aeronautic, computer, electro-mechanical, pharmaceutical and mining industries and more. 45 scientists have been awarded the Nobel Prize over the past century for work that is either directly or indirectly related to crystallography, and yet it remains a field relatively unknown to the general public. This year UNESCO has joined forces with the International Union of Crystallography to promote education and public awareness, and we are delighted to contribute to this effort with the Dorothy Hodgkin Symposium. PROGRAMME 2:45 pm Tea & Coffee, Somerville College, Flora Anderson Hall 3:00 pm Hidden Glory, Dorothy Hodgkin in her own words, Somerville College, Flora Anderson Hall A filmed performance of a short, one-woman play about the life and work of Dorothy Hodgkin, followed by Q&A with the playwright Georgina Ferry 4:00 pm Registration, Mathematical Institute, University of Oxford 4:10 pm Welcome, Mathematical Institute, -

Fetch-Limited Barrier Islands: Overlooked Coastal Landforms

SECTION MEETING: Rocky Mountain, p. 14 VOL. 17, No. 3 A PUBLICATION OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA MARCH 2007 Fetch-limited barrier islands: Overlooked coastal landforms Inside: Call for Committee Service, p. 18 Groundwork—Scientific uncertainty and public policy: Moving on without all the answers, p. 28 It’s Not Just Software. It’s RockWare. For Over 23 Years. RockWorks™ LP360™ 3D Subsurface Data LIDAR extension for ArcGIS Management, Analysis, and The LP360 LIDAR extension Visualization uses a specially-designed ™ All-in-one tool that allows you ArcMap data layer to draw to visualize, interpret and points directly from LAS fi les present your surface and thereby integrating LIDAR data sub-surface data. Now with with the rest of your GIS. LIDAR Access Database for powerful data can be viewed together queries, built-in import/export with data in any format ™ tools for LogPlot data, and LAS supported by ArcGIS , including and IHS import. vector data, rasters, and imagery. Free trial avialable at www.rockware.com. $1,999 Commercial/$749 Academic $2,995 AqQA™ ChemStat™ Spreadsheet for Water Analysis Ground Water Data Statistical • Create Piper diagram, Stiff Analysis diagram, Ternary, and eight other The easiest and fastest applica- plot types tion available for the statistical • Instant unit conversion — shift analysis of ground water moni- effortlessly among units toring data. ChemStat includes • Check water analyses for most statistical analysis methods internal consistency described in the 1989 and 1992 • Manage water data in a USEPA documents, U.S. Navy spreadsheet Statistical Analysis Guidance document, and other guidance Free trial avialable at www.rockware.com. -

Guidelines for Science: Evidence and Checklists

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Marketing Papers Wharton Faculty Research 1-24-2017 Guidelines for Science: Evidence and Checklists J. Scott Armstrong University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Kesten C. Green University of South Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/marketing_papers Part of the Econometrics Commons, and the Marketing Commons Recommended Citation Armstrong, J. S., & Green, K. C. (2017). Guidelines for Science: Evidence and Checklists. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/marketing_papers/181 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/marketing_papers/181 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Guidelines for Science: Evidence and Checklists Abstract Problem: The scientific method is unrivalled as a basis for generating useful knowledge, yet research papers published in management, economics, and other social sciences fields often ignore scientific principles. What, then, can be done to increase the publication of useful scientific papers? Methods: Evidence on researchers’ compliance with scientific principles was examined. Guidelines aimed at reducing violations were then derived from established definitions of the scientific method. Findings: Violations of the principles of science are encouraged by: (a) funding for advocacy research; (b) regulations that limit what research is permitted, how it must be designed, and what must be reported; (c) political suppression of scientists’ speech; (d) universities’ use of invalid criteria to evaluate research—such as grant money and counting of publications without regard to usefulness; (e) journals’ use of invalid criteria for deciding which papers to publish—such as the use of statistical significance tests. Solutions: We created a checklist of 24 evidence-based operational guidelines to help researchers comply with scientific principles (valid inputs). -

Finding Aid to the Roy D. Bridges Jr. Papers, 1957-2010

FINDING AID TO THE ROY D. BRIDGES JR. PAPERS, 1957-2010 Purdue University Libraries Virginia Kelly Karnes Archives and Special Collections Research Center 504 West State Street West Lafayette, Indiana 47907-2058 (765) 494-2839 http://www.lib.purdue.edu/spcol © 2015 Purdue University Libraries. All rights reserved. Processed by: Mary A. Sego, January 14, 2015 Descriptive Summary Creator Information Bridges, Roy D., Jr., 1943- Title Roy D. Bridges Jr. papers Collection Identifier MSA 6 Date Span 1957-2010 Abstract This collection includes documents, photographs, awards and certificates, textbooks, briefs and records, artifacts, audiovisual materials, and scrapbooks that document the life and career of astronaut and retired United States Air Force Major General Roy Bridges Jr. Included are numerous awards, drawings, and personalized photographs and mementos given to Bridges in appreciation of his service and leadership. Extent 68.90 cubic feet (24 cubic feet boxes, 2 legal mss boxes, 37 letter mss boxes, 12, ½ letter mss boxes, 6 small flat boxes, 3 medium flat and 8 large flat boxes, and 3 oversized, loose wrapped items) Finding Aid Author Mary A. Sego Languages English Repository Virginia Kelly Karnes Archives and Special Collections Research Center, Purdue University Libraries Administrative Information Location ASC and ASC-R Information: Access Collection is open for research. The collection is stored offsite; 24 hours Restrictions: notice is required to access the collection. Acquisition Donated by Roy D. Bridges Jr., 2009-2013. Information: Accession 20090409 Number: 20091111 20100104 12/2/2015 2 20100421 20100604 20100910 20110119 20110427 20110505 20110622 20120405 20130308 20130425 Preferred MSA 6, Roy D. Bridges Jr.