Systematics, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Orb-Weaving Spiders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SPIDER FAMILIES of EUROPE: Keys, Diagnoses and Diversity DIE

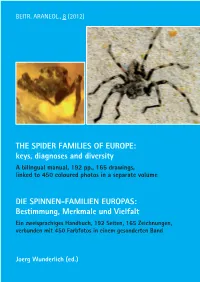

BEITR. ARANEOL., 8 (2012) THE SPIDER FAMILIES OF EUROPE: keys, diagnoses and diversity A bilingual manual, 192 pp., 165 drawings, linked to 450 coloured photos in a separate volume DIE SPINNEN-FAMILIEN EUROPAS: Bestimmung, Merkmale und Vielfalt Ein zweisprachiges Handbuch, 192 Seiten, 165 Zeichnungen, verbunden mit 450 Farbfotos in einem gesonderten Band Joerg Wunderlich (ed.) BEITR. ARANEOL., 8 (2012) Photos on the front cover / Fotos auf dem Buchdeckel: On the left: Frontal aspect of a Jumping Spider (Salticidae) in Eocene Baltic amber. Note the huge anterior median eyes. Links: Eine Springspinne in Baltischem Bernstein, Vorderansicht. Man beachte die sehr großen, scheinwerferartig nach vorn gerichteten vorderen Mittelaugen. On the right: A male sparassid spider of Eusparassus dufouri SIMON on sand, Portugal. Note the laterigrade leg position of this very large spider, which legs spun seven cms. Rechts: Männliche Riesenkrabbenspinne (Sparassidae) (Eusparassus dufouri) auf Sand, Portugal. Man beachte die zur Seite gerichteten Beine dieser sehr großen Spinne mit einer Spannweite der Vorderbeine von sieben Zentimetern. 1 2 BEITR. ARANEOL., 8 (2012) THE SPIDER FAMILIES OF EUROPE: keys, diagnoses and diversity A bilingual manual, 192 pp., 165 drawings, linked to 450 coloured photos in a separate volume DIE SPINNEN-FAMILIEN EUROPAS: Bestimmung, Merkmale und Vielfalt Ein zweisprachiges Handbuch, 192 Seiten, 165 Zeichnungen, verbunden mit 450 Farbfotos in einem gesonderten Band Editor and author: JOERG WUNDERLICH © Publishing House: Joerg Wunderlich, 69493 Hirschberg, Germany Print: M + M Druck GmbH, Heidelberg. Orders for this and other volume(s) of the Beitr. Araneol. (see p. 192): Publishing House Joerg Wunderlich Oberer Haeuselbergweg 24 69493 Hirschberg Germany E-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-3-931473-14-2 3 BEITR. -

Further Study of Two Chinese Cave Spiders 77 Doi: 10.3897/Zookeys.870.35971 RESEARCH ARTICLE Launched to Accelerate Biodiversity Research

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 870: 77–100 (2019) Further study of two Chinese cave spiders 77 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.870.35971 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Further study of two Chinese cave spiders (Araneae, Mysmenidae), with description of a new genus Chengcheng Feng1, Jeremy A. Miller2, Yucheng Lin1, Yunfei Shu1 1 Key Laboratory of Bio-Resources and Eco-Environment of Ministry of Education, College of Life Sciences, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610065, Sichuan, China 2 Department of Biodiversity Discovery, Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Postbus 9517 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands Corresponding author: Yucheng Lin ([email protected]) Academic editor: Charles Haddad | Received 08 May 2019 | Accepted 09 July 2019 | Published 7 August 2019 http://zoobank.org/4167F0DE-2097-4F3D-A608-3C8365754F99 Citation: Feng C, Miller JA, Lin Y, Shu Y(2019) Further study of two Chinese cave spiders (Araneae, Mysmenidae), with description of a new genus. ZooKeys 870: 77–100. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.870.35971 Abstract The current paper expands knowledge of two Chinese cave spider species originally described in the genus Maymena Gertsch, 1960: M. paquini Miller, Griswold & Yin, 2009 and M. kehen Miller, Griswold & Yin, 2009. With the exception of these two species, the genus Maymena is endemic to the western hemisphere, and new evidence presented here supports the creation of a new genus for the Chinese species, which we name Yamaneta gen. nov. The male of Y. kehen is described for the first time. Detailed illustrations of the habitus, male palps and epigyne are provided for these two species, as well as descriptions of their webs. -

Comparative Functional Morphology of Attachment Devices in Arachnida

Comparative functional morphology of attachment devices in Arachnida Vergleichende Funktionsmorphologie der Haftstrukturen bei Spinnentieren (Arthropoda: Arachnida) DISSERTATION zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) an der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel vorgelegt von Jonas Otto Wolff geboren am 20. September 1986 in Bergen auf Rügen Kiel, den 2. Juni 2015 Erster Gutachter: Prof. Stanislav N. Gorb _ Zweiter Gutachter: Dr. Dirk Brandis _ Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 17. Juli 2015 _ Zum Druck genehmigt: 17. Juli 2015 _ gez. Prof. Dr. Wolfgang J. Duschl, Dekan Acknowledgements I owe Prof. Stanislav Gorb a great debt of gratitude. He taught me all skills to get a researcher and gave me all freedom to follow my ideas. I am very thankful for the opportunity to work in an active, fruitful and friendly research environment, with an interdisciplinary team and excellent laboratory equipment. I like to express my gratitude to Esther Appel, Joachim Oesert and Dr. Jan Michels for their kind and enthusiastic support on microscopy techniques. I thank Dr. Thomas Kleinteich and Dr. Jana Willkommen for their guidance on the µCt. For the fruitful discussions and numerous information on physical questions I like to thank Dr. Lars Heepe. I thank Dr. Clemens Schaber for his collaboration and great ideas on how to measure the adhesive forces of the tiny glue droplets of harvestmen. I thank Angela Veenendaal and Bettina Sattler for their kind help on administration issues. Especially I thank my students Ingo Grawe, Fabienne Frost, Marina Wirth and André Karstedt for their commitment and input of ideas. -

Casting a Sticky Trap: SPIDERS and Their Predatory Ways

Casting a Sticky Trap: SPIDERS and Their Predatory Ways Bennett C. Moulder, ISM Research Associate and Professor Emeritus, Illinois College, Jacksonville, Illinois ating insects and other small sticky silk, capable of trapping and holding to the spot, and impales the insect with its arthropods is what spiders do for even relatively large an powerful insect prey. long chelicerae. First using her mouthparts a living. That spiders are an Damage to the orb caused by wind or strug- to cut a small slit in the tube, the spider enormously successful group of gling prey can be quickly repaired, or the then pulls the insect inside. After her meal, animals is testimony to how efficient they entire can be web taken down and replaced. the spider repairs the tear in the tube, re- Eare at catching their prey. Most insects move Many orb weavers replace their tattered web sumes her position below ground, and swiftly and, for their size, are quite powerful. with a new one every day. awaits the next victim. “For spiders to capture such prey, they have, Other spiders do not utilize webs for prey Mastophora, the bolas spider, is a mem- as a group, developed an impressive arsenal capture. Crab spiders, perfectly camouflaged ber of the family Araneidae, the typical orb of weapons and a variety of strategies. against their background, lie in wait on flow- weavers. This small spider has abandoned Except for one small family (Ul- ers or on the bark of trees to ambush unsus- the practice of orb web construction alto- oboridae), all spiders in Illinois have venom pecting insects. -

Representation of Different Exact Numbers of Prey by a Spider-Eating Predator Rsfs.Royalsocietypublishing.Org Fiona R

Representation of different exact numbers of prey by a spider-eating predator rsfs.royalsocietypublishing.org Fiona R. Cross1,2 and Robert R. Jackson1,2 1School of Biological Sciences, University of Canterbury, Private Bag 4800, Christchurch, New Zealand 2International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology, Thomas Odhiambo Campus, PO Box 30, Mbita Point, Kenya Research FRC, 0000-0001-8266-4270; RRJ, 0000-0003-4638-847X Our objective was to use expectancy-violation methods for determining Cite this article: Cross FR, Jackson RR. 2017 whether Portia africana, a salticid spider that specializes in eating other Representation of different exact numbers of spiders, is proficient at representing exact numbers of prey. In our exper- prey by a spider-eating predator. Interface iments, we relied on this predator’s known capacity to gain access to prey Focus 7: 20160035. by following pre-planned detours. After Portia first viewed a scene consist- http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2016.0035 ing of a particular number of prey items, it could then take a detour during which the scene went out of view. Upon reaching a tower at the end of the detour, Portia could again view a scene, but now the number of One contribution of 12 to a theme issue prey items might be different. We found that, compared with control trials ‘Convergent minds: the evolution of cognitive in which the number was the same as before, Portia’s behaviour was complexity in nature’. significantly different in most instances when we made the following changes in number: 1 versus 2, 1 versus 3, 1 versus 4, 2 versus 3, 2 versus 4 or 2 versus 6. -

Howard Associate Professor of Natural History and Curator Of

INGI AGNARSSON PH.D. Howard Associate Professor of Natural History and Curator of Invertebrates, Department of Biology, University of Vermont, 109 Carrigan Drive, Burlington, VT 05405-0086 E-mail: [email protected]; Web: http://theridiidae.com/ and http://www.islandbiogeography.org/; Phone: (+1) 802-656-0460 CURRICULUM VITAE SUMMARY PhD: 2004. #Pubs: 138. G-Scholar-H: 42; i10: 103; citations: 6173. New species: 74. Grants: >$2,500,000. PERSONAL Born: Reykjavík, Iceland, 11 January 1971 Citizenship: Icelandic Languages: (speak/read) – Icelandic, English, Spanish; (read) – Danish; (basic) – German PREPARATION University of Akron, Akron, 2007-2008, Postdoctoral researcher. University of British Columbia, Vancouver, 2005-2007, Postdoctoral researcher. George Washington University, Washington DC, 1998-2004, Ph.D. The University of Iceland, Reykjavík, 1992-1995, B.Sc. PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATIONS University of Vermont, Burlington. 2016-present, Associate Professor. University of Vermont, Burlington, 2012-2016, Assistant Professor. University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras, 2008-2012, Assistant Professor. National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, 2004-2007, 2010- present. Research Associate. Hubei University, Wuhan, China. Adjunct Professor. 2016-present. Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavík, 1995-1998. Researcher (Icelandic invertebrates). Institute of Biology, University of Iceland, Reykjavík, 1993-1994. Research Assistant (rocky shore ecology). GRANTS Institute of Museum and Library Services (MA-30-19-0642-19), 2019-2021, co-PI ($222,010). Museums for America Award for infrastructure and staff salaries. National Geographic Society (WW-203R-17), 2017-2020, PI ($30,000). Caribbean Caves as biodiversity drivers and natural units for conservation. National Science Foundation (IOS-1656460), 2017-2021: one of four PIs (total award $903,385 thereof $128,259 to UVM). -

Araneae, Theridiidae)

Phelsuma 14; 49-89 Theridiid or cobweb spiders of the granitic Seychelles islands (Araneae, Theridiidae) MICHAEL I. SAARISTO Zoological Museum, Centre for Biodiversity University of Turku,FIN-20014 Turku FINLAND [micsaa@utu.fi ] Abstract. - This paper describes 8 new genera, namely Argyrodella (type species Argyrodes pusillus Saaristo, 1978), Bardala (type species Achearanea labarda Roberts, 1982), Nanume (type species Theridion naneum Roberts, 1983), Robertia (type species Theridion braueri (Simon, 1898), Selimus (type species Theridion placens Blackwall, 1877), Sesato (type species Sesato setosa n. sp.), Spinembolia (type species Theridion clabnum Roberts, 1978), and Stoda (type species Theridion libudum Roberts, 1978) and one new species (Sesato setosa n. sp.). The following new combinations are also presented: Phycosoma spundana (Roberts, 1978) n. comb., Argyrodella pusillus (Saaristo, 1978) n. comb., Rhomphaea recurvatus (Saaristo, 1978) n. comb., Rhomphaea barycephalus (Roberts, 1983) n. comb., Bardala labarda (Roberts, 1982) n. comb., Moneta coercervus (Roberts, 1978) n. comb., Nanume naneum (Roberts, 1983) n. comb., Parasteatoda mundula (L. Koch, 1872) n. comb., Robertia braueri (Simon, 1898). n. comb., Selimus placens (Blackwall, 1877) n. comb., Sesato setosa n. gen, n. sp., Spinembolia clabnum (Roberts, 1978) n. comb., and Stoda libudum (Roberts, 1978) n. comb.. Also the opposite sex of four species are described for the fi rst time, namely females of Phycosoma spundana (Roberts, 1978) and P. menustya (Roberts, 1983) and males of Spinembolia clabnum (Roberts, 1978) and Stoda libudum (Roberts, 1978). Finally the morphology and terminology of the male and female secondary genital organs are discussed. Key words. - copulatory organs, morphology, Seychelles, spiders, Theridiidae. INTRODUCTION Theridiids or comb-footed spiders are very variable in general apperance often with considerable sexual dimorphism. -

Spider Biology Unit

Spider Biology Unit RET I 2000 and RET II 2002 Sally Horak Cortland Junior Senior High School Grade 7 Science Support for Cornell Center for Materials Research is provided through NSF Grant DMR-0079992 Copyright 2004 CCMR Educational Programs. All rights reserved. Spider Biology Unit Overview Grade level- 7th grade life science- heterogeneous classes Theme- The theme of this unit is to understand the connection between form and function in living things and to investigate what humans can learn from other living things. Schedule- projected time for this unit is 3 weeks Outline- *Activity- Unique spider facts *PowerPoint presentation giving a general overview of the biology of spiders with specific examples of interest *Lab- Spider observations *Cross-discipline activity #1- Spider short story *Activity- Web Spiders and Wandering spiders *Project- create a 3-D model of a spider that is anatomically correct *Project- research a specific spider and create a mini-book of information. *Activity- Spider defense pantomime *PowerPoint presentation on Spider Silk *Lab- Fiber Strength and Elasticity *Lab- Polymer Lab *Project- Spider silk challenge Support for Cornell Center for Materials Research is provided through NSF Grant DMR-0079992 Copyright 2004 CCMR Educational Programs. All rights reserved. Correlation to the NYS Intermediate Level Science Standards (Core Curriculum, Grades 5-8): General Skills- #1. Follow safety procedures in the classroom and laboratory. #2. Safely and accurately use the following measurement tools- Metric ruler, triple beam balance #3. Use appropriate units for measured or calculated values #4. Recognize and analyze patterns and trends #5. Classify objects according to an established scheme and a student-generated scheme. -

Phylogeny of Entelegyne Spiders: Affinities of the Family Penestomidae

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 55 (2010) 786–804 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Phylogeny of entelegyne spiders: Affinities of the family Penestomidae (NEW RANK), generic phylogeny of Eresidae, and asymmetric rates of change in spinning organ evolution (Araneae, Araneoidea, Entelegynae) Jeremy A. Miller a,b,*, Anthea Carmichael a, Martín J. Ramírez c, Joseph C. Spagna d, Charles R. Haddad e, Milan Rˇezácˇ f, Jes Johannesen g, Jirˇí Král h, Xin-Ping Wang i, Charles E. Griswold a a Department of Entomology, California Academy of Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Drive, Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, CA 94118, USA b Department of Terrestrial Zoology, Nationaal Natuurhistorisch Museum Naturalis, Postbus 9517 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands c Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales – CONICET, Av. Angel Gallardo 470, C1405DJR Buenos Aires, Argentina d William Paterson University of New Jersey, 300 Pompton Rd., Wayne, NJ 07470, USA e Department of Zoology & Entomology, University of the Free State, P.O. Box 339, Bloemfontein 9300, South Africa f Crop Research Institute, Drnovská 507, CZ-161 06, Prague 6-Ruzyneˇ, Czech Republic g Institut für Zoologie, Abt V Ökologie, Universität Mainz, Saarstraße 21, D-55099, Mainz, Germany h Laboratory of Arachnid Cytogenetics, Department of Genetics and Microbiology, Faculty of Science, Charles University in Prague, Prague, Czech Republic i College of Life Sciences, Hebei University, Baoding 071002, China article info abstract Article history: Penestomine spiders were first described from females only and placed in the family Eresidae. Discovery Received 20 April 2009 of the male decades later brought surprises, especially in the morphology of the male pedipalp, which Revised 17 February 2010 features (among other things) a retrolateral tibial apophysis (RTA). -

SA Spider Checklist

REVIEW ZOOS' PRINT JOURNAL 22(2): 2551-2597 CHECKLIST OF SPIDERS (ARACHNIDA: ARANEAE) OF SOUTH ASIA INCLUDING THE 2006 UPDATE OF INDIAN SPIDER CHECKLIST Manju Siliwal 1 and Sanjay Molur 2,3 1,2 Wildlife Information & Liaison Development (WILD) Society, 3 Zoo Outreach Organisation (ZOO) 29-1, Bharathi Colony, Peelamedu, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641004, India Email: 1 [email protected]; 3 [email protected] ABSTRACT Thesaurus, (Vol. 1) in 1734 (Smith, 2001). Most of the spiders After one year since publication of the Indian Checklist, this is described during the British period from South Asia were by an attempt to provide a comprehensive checklist of spiders of foreigners based on the specimens deposited in different South Asia with eight countries - Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. The European Museums. Indian checklist is also updated for 2006. The South Asian While the Indian checklist (Siliwal et al., 2005) is more spider list is also compiled following The World Spider Catalog accurate, the South Asian spider checklist is not critically by Platnick and other peer-reviewed publications since the last scrutinized due to lack of complete literature, but it gives an update. In total, 2299 species of spiders in 67 families have overview of species found in various South Asian countries, been reported from South Asia. There are 39 species included in this regions checklist that are not listed in the World Catalog gives the endemism of species and forms a basis for careful of Spiders. Taxonomic verification is recommended for 51 species. and participatory work by arachnologists in the region. -

Taxonomic Revision and Phylogenetic Hypothesis for the Jumping Spider Subfamily Ballinae (Araneae, Salticidae)

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title Taxonomic revision and phylogenetic hypothesis for the jumping spider subfamily Ballinae (Araneae, Salticidae) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5x19n4mz Journal Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 142(1) ISSN 0024-4082 Author Benjamin, S P Publication Date 2004-09-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Blackwell Science, LtdOxford, UKZOJZoological Journal of the Linnean Society0024-4082The Lin- nean Society of London, 2004? 2004 1421 182 Original Article S. P. BENJAMINTAXONOMY AND PHYLOGENY OF BALLINAE Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2004, 142, 1–82. With 69 figures Taxonomic revision and phylogenetic hypothesis for the jumping spider subfamily Ballinae (Araneae, Salticidae) SURESH P. BENJAMIN* Department of Integrative Biology, Section of Conservation Biology (NLU), University of Basel, St. Johanns-Vorstadt 10, CH-4056 Basel, Switzerland Received July 2003; accepted for publication February 2004 The subfamily Ballinae is revised. To test its monophyly, 41 morphological characters, including the first phyloge- netic use of scale morphology in Salticidae, were scored for 16 taxa (1 outgroup and 15 ingroup). Parsimony analysis of these data supports monophyly based on five unambiguous synapomorphies. The paper provides new diagnoses, descriptions of new genera, species, and a key to the genera. At present, Ballinae comprises 13 nominal genera, three of them new: Afromarengo, Ballus, Colaxes, Cynapes, Indomarengo, Leikung, Marengo, Philates and Sadies. Copocrossa, Mantisatta, Pachyballus and Padilla are tentatively included in the subfamily. Nine new species are described and illustrated: Colaxes horton, C. wanlessi, Philates szutsi, P. thaleri, P. zschokkei, Indomarengo chandra, I. -

Five Papers on Fossil and Extant Spiders

BEITR. ARANEOL., 13 (2020) Joerg Wunderlich FIVE PAPERS ON FOSSIL AND EXTANT SPIDERS BEITR. ARANEOL., 13 (2020: 1–176) FIVE PAPERS ON FOSSIL AND EXTANT SPIDERS NEW AND RARE FOSSIL SPIDERS (ARANEAE) IN BALTIC AND BUR- MESE AMBERS AS WELL AS EXTANT AND SUBRECENT SPIDERS FROM THE WESTERN PALAEARCTIC AND MADAGASCAR, WITH NOTES ON SPIDER PHYLOGENY, EVOLUTION AND CLASSIFICA- TION JOERG WUNDERLICH, D-69493 Hirschberg, e-mail: [email protected]. Website: www.joergwunderlich.de. – Here a digital version of this book can be found. © Publishing House, author and editor: Joerg Wunderlich, 69493 Hirschberg, Germany. BEITRAEGE ZUR ARANEOLOGIE (BEITR. ARANEOL.), 13. ISBN 978-3-931473-19-8 The papers of this volume are available on my website. Print: Baier Digitaldruck GmbH, Heidelberg. 1 BEITR. ARANEOL., 13 (2020) Photo on the book cover: Dorsal-lateral aspect of the male tetrablemmid spider Elec- troblemma pinnae n. sp. in Burmit, body length 1.5 mm. See the photo no. 17 p. 160. Fossil spider of the year 2020. Acknowledgements: For corrections of parts of the present manuscripts I thank very much my dear wife Ruthild Schöneich. For the professional preparation of the layout I am grateful to Angelika and Walter Steffan in Heidelberg. CONTENTS. Papers by J. WUNDERLICH, with the exception of the paper p. 22 page Introduction and personal note………………………………………………………… 3 Description of four new and few rare spider species from the Western Palaearctic (Araneae: Dysderidae, Linyphiidae and Theridiidae) …………………. 4 Resurrection of the extant spider family Sinopimoidae LI & WUNDERLICH 2008 (Araneae: Araneoidea) ……………………………………………………………...… 19 Note on fossil Atypidae (Araneae) in Eocene European ambers ………………… 21 New and already described fossil spiders (Araneae) of 20 families in Mid Cretaceous Burmese amber with notes on spider phylogeny, evolution and classification; by J.