Ing the Real: Identity Politics and Urban Space in Mainstream Norwegian Rap Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daft Punk, La Toile Et Le Disco: Revival Culturel a L'heure Du Numerique

Daft Punk, la Toile et le disco: Revival culturel a l’heure du numerique Philippe Poirrier To cite this version: Philippe Poirrier. Daft Punk, la Toile et le disco: Revival culturel a l’heure du numerique. French Cultural Studies, SAGE Publications, 2015, 26 (3), pp.368-381. 10.1177/0957155815587245. halshs- 01232799 HAL Id: halshs-01232799 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01232799 Submitted on 24 Nov 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. © Philippe Poirrier, « Daft Punk, la Toile et le disco. Revival culturel à l’heure du numérique », French Cultural Studies, août 2015, n° 26-3, p. 368-381. Daft Punk, la Toile et le disco Revival culturel à l’heure du numérique PHILIPPE POIRRIER Université de Bourgogne 26 janvier 2014, Los Angeles, 56e cérémonie des Grammy Awards : le duo français de musique électronique Daft Punk remporte cinq récompenses, dont celle de meilleur album de l’année pour Random Access Memories, et celle de meilleur enregistrement pour leur single Get Lucky ; leur prestation live, la première depuis la sortie de l’album, avec le concours de Stevie Wonder, transforme le Staples Center, le temps du titre Get Lucky, en discothèque. -

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Joesell Radford, BA Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Professor Beverly Gordon, Advisor Professor Adrienne Dixson Copyrighted by Crystal Joesell Radford 2011 Abstract This study critically analyzes rap through an interdisciplinary framework. The study explains rap‟s socio-cultural history and it examines the multi-generational, classed, racialized, and gendered identities in rap. Rap music grew out of hip-hop culture, which has – in part – earned it a garnering of criticism of being too “violent,” “sexist,” and “noisy.” This criticism became especially pronounced with the emergence of the rap subgenre dubbed “gangsta rap” in the 1990s, which is particularly known for its sexist and violent content. Rap music, which captures the spirit of hip-hop culture, evolved in American inner cities in the early 1970s in the South Bronx at the wake of the Civil Rights, Black Nationalist, and Women‟s Liberation movements during a new technological revolution. During the 1970s and 80s, a series of sociopolitical conscious raps were launched, as young people of color found a cathartic means of expression by which to describe the conditions of the inner-city – a space largely constructed by those in power. Rap thrived under poverty, police repression, social policy, class, and gender relations (Baker, 1993; Boyd, 1997; Keyes, 2000, 2002; Perkins, 1996; Potter, 1995; Rose, 1994, 2008; Watkins, 1998). -

Hip Hop Pedagogies of Black Women Rappers Nichole Ann Guillory Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Schoolin' women: hip hop pedagogies of black women rappers Nichole Ann Guillory Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Guillory, Nichole Ann, "Schoolin' women: hip hop pedagogies of black women rappers" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 173. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/173 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SCHOOLIN’ WOMEN: HIP HOP PEDAGOGIES OF BLACK WOMEN RAPPERS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Curriculum and Instruction by Nichole Ann Guillory B.S., Louisiana State University, 1993 M.Ed., University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 1998 May 2005 ©Copyright 2005 Nichole Ann Guillory All Rights Reserved ii For my mother Linda Espree and my grandmother Lovenia Espree iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am humbled by the continuous encouragement and support I have received from family, friends, and professors. For their prayers and kindness, I will be forever grateful. I offer my sincere thanks to all who made sure I was well fed—mentally, physically, emotionally, and spiritually. I would not have finished this program without my mother’s constant love and steadfast confidence in me. -

Lesbian and Gay Music

Revista Eletrônica de Musicologia Volume VII – Dezembro de 2002 Lesbian and Gay Music by Philip Brett and Elizabeth Wood the unexpurgated full-length original of the New Grove II article, edited by Carlos Palombini A record, in both historical documentation and biographical reclamation, of the struggles and sensi- bilities of homosexual people of the West that came out in their music, and of the [undoubted but unacknowledged] contribution of homosexual men and women to the music profession. In broader terms, a special perspective from which Western music of all kinds can be heard and critiqued. I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 II. (HOMO)SEXUALIT Y AND MUSICALIT Y 2 III. MUSIC AND THE LESBIAN AND GAY MOVEMENT 7 IV. MUSICAL THEATRE, JAZZ AND POPULAR MUSIC 10 V. MUSIC AND THE AIDS/HIV CRISIS 13 VI. DEVELOPMENTS IN THE 1990S 14 VII. DIVAS AND DISCOS 16 VIII. ANTHROPOLOGY AND HISTORY 19 IX. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 24 X. EDITOR’S NOTES 24 XI. DISCOGRAPHY 25 XII. BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 What Grove printed under ‘Gay and Lesbian Music’ was not entirely what we intended, from the title on. Since we were allotted only two 2500 words and wrote almost five times as much, we inevitably expected cuts. These came not as we feared in the more theoretical sections, but in certain other tar- geted areas: names, popular music, and the role of women. Though some living musicians were allowed in, all those thought to be uncomfortable about their sexual orientation’s being known were excised, beginning with Boulez. -

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

Jim Jones Spike Lee

Jim jones spike lee FRED THE GODSON KICKS OFF PROMO FOR HIS UPCOMING RELEASE "GORDO FREDERICO" IN THIS. Fred the Godson ft Jim Jones - Spike Lee on location video shoot - Duration: Jace Media 6, views. DOWNLOAD LINK: Fred The Godson Ft Jim Jones. Spike Lee Instrumental. Stream Spike Lee (Feat. Jim Jones) by FREDTHEGODSON from desktop or your mobile device. New York City!!!!! in the house love seeing uptown niggas working together, doing there thing and showing the. Fred The Godson Ft Jim Jones And Plf Dblock Spike Lee D Block Remix mp3. Fred The FRED DA GODSON FEAT JIM JONES " SPIKE LEE " 3. Download Mixtape | Free Mixtapes Powered by Fred The Godson releases a video for, "Spike Lee,' and his new mixtape, "Gordo. Behind The Scenes: Fred The Godson “Spike Lee” (feat. music video shoot for Fred The Godson's record “Spike Lee” featuring Jim Jones. Fred The Godson – Spike Lee (feat. Jim Jones). By GHØST August 15, Jim Jones Song: “Spike Lee” Producer: AlistFame. Mixtape. 25), Jim Jones and his partner of 11 years Chrissy Lampkin in a recent NYC Will Screen Spike Lee's 'Crooklyn' To Unite The People And. Explore Spike Lee, Hip Hop Videos, and more! All I Want for Christmas is My Two Front Teeth - Spike Jones · Front TeethChristmas MusicMerry. Video: Fred The Godson (@fredthegodson) Ft Jim Jones (@jimjonescapo) “Spike Lee”. jim jones gigabyte ft avon carter jimjonescapo download free mp3. Fred The Godson x Jim Jones - Spike Lee - AlistFame. AlistFame. 1K Plays. 2K Downloads. Download View Profile. $ Your Name. Email Address. Fresh off releasing is Gordo Frederico mixtape earlier today, Fred The Godson drops off visuals for his Spike Lee tribute featuring Jim Jones. -

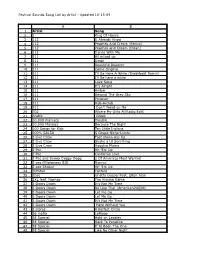

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

The Moral Priorities of Rap Listeners

Published: Nzinga, K.L.K., & Medin, D.L. (2018). The Moral Priorities of Rap Listeners. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 312-342. http://booKsandjournals.brillonline.com/content/journals/10.1163/15685373-12340033 The Moral Priorities of Rap Listeners Kalonji L.K. NZINGA Douglas L. MEDIN Northwestern University A Cross-cultural approach to moral psychology starts from researchers withholding judgments about universal right and wrong and instead exploring community members’ values and what they subjeCtively perCeive to be moral or immoral in their loCal Context. This study seeks to identify the moral ConCerns that are most relevant to listeners of hip- hop music. We use validated psyChologiCal surveys inCluding the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (Graham, Haidt, & Nosek 2009) to assess whiCh moral ConCerns are most central to hip-hop listeners. Results show that hip-hop listeners prioritize concerns of justiCe and authentiCity more than non-listeners and deprioritize ConCerns about respeCting authority. These results show that the ConCept of the “good person” within the hip-hop subculture is fundamentally a person that is oriented towards soCial justiCe, rebellion against the status quo, and a deep devotion to keeping it real. Results are followed by a disCussion of the role that youth subCultures have in soCializing young people to prioritize Certain virtues over others as they develop their moral identity. 1. Introduction Many AmeriCan rappers inCluding KendriCk Lamar (2010), Snoop Dogg (2015), and Busta Rhymes (2006) have delivered the following CatCh phrase in their lyriCs: “You Can take me out the hood, but you Can’t take the hood out of me.” They proClaim that there are Certain aspeCts of the “hood” lifestyle and value system that, onCe they are part of you, direCt how you perCeive the world and behave in it. -

ENG 350 Summer12

ENG 350: THE HISTORY OF HIP-HOP With your host, Dr. Russell A. Potter, a.k.a. Professa RAp Monday - Thursday, 6:30-8:30, Craig-Lee 252 http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ In its rise to the top of the American popular music scene, Hip-hop has taken on all comers, and issued beatdown after beatdown. Yet how many of its fans today know the origins of the music? Sure, people might have heard something of Afrika Bambaataa or Grandmaster Flash, but how about the Last Poets or Grandmaster CAZ? For this class, we’ve booked a ride on the wayback machine which will take us all the way back to Hip-hop’s precursors, including the Blues, Calypso, Ska, and West African griots. From there, we’ll trace its roots and routes through the ‘parties in the park’ in the late 1970’s, the emergence of political Hip-hop with Public Enemy and KRS-One, the turn towards “gangsta” style in the 1990’s, and on into the current pantheon of rappers. Along the way, we’ll take a closer look at the essential elements of Hip-hop culture, including Breaking (breakdancing), Writing (graffiti), and Rapping, with a special look at the past and future of turntablism and digital sampling. Our two required textbook are Bradley and DuBois’s Anthology of Rap (Yale University Press) and Neal and Forman’s That's the Joint: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader are both available at the RIC campus store. Films shown in part or in whole will include Bamboozled, Style Wars, The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy, Wild Style, and Zebrahead; there will is also a course blog with a discussion board and a wide array of links to audio and text resources at http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ WRITTEN WORK: An informal response to our readings and listenings is due each week on the blog. -

Disco Top 15 Histories

10. Billboard’s Disco Top 15, Oct 1974- Jul 1981 Recording, Act, Chart Debut Date Disco Top 15 Chart History Peak R&B, Pop Action Satisfaction, Melody Stewart, 11/15/80 14-14-9-9-9-9-10-10 x, x African Symphony, Van McCoy, 12/14/74 15-15-12-13-14 x, x After Dark, Pattie Brooks, 4/29/78 15-6-4-2-2-1-1-1-1-1-1-2-3-3-5-5-5-10-13 x, x Ai No Corrida, Quincy Jones, 3/14/81 15-9-8-7-7-7-5-3-3-3-3-8-10 10,28 Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us, McFadden & Whitehead, 5/5/79 14-12-11-10-10-10-10 1,13 Ain’t That Enough For You, JDavisMonsterOrch, 9/2/78 13-11-7-5-4-4-7-9-13 x,89 All American Girls, Sister Sledge, 2/21/81 14-9-8-6-6-10-11 3,79 All Night Thing, Invisible Man’s Band, 3/1/80 15-14-13-12-10-10 9,45 Always There, Side Effect, 6/10/76 15-14-12-13 56,x And The Beat Goes On, Whispers, 1/12/80 13-2-2-2-1-1-2-3-3-4-11-15 1,19 And You Call That Love, Vernon Burch, 2/22/75 15-14-13-13-12-8-7-9-12 x,x Another One Bites The Dust, Queen, 8/16/80 6-6-3-3-2-2-2-3-7-12 2,1 Another Star, Stevie Wonder, 10/23/76 13-13-12-6-5-3-2-3-3-3-5-8 18,32 Are You Ready For This, The Brothers, 4/26/75 15-14-13-15 x,x Ask Me, Ecstasy,Passion,Pain, 10/26/74 2-4-2-6-9-8-9-7-9-13post peak 19,52 At Midnight, T-Connection, 1/6/79 10-8-7-3-3-8-6-8-14 32,56 Baby Face, Wing & A Prayer, 11/6/75 13-5-2-2-1-3-2-4-6-9-14 32,14 Back Together Again, R Flack & D Hathaway, 4/12/80 15-11-9-6-6-6-7-8-15 18,56 Bad Girls, Donna Summer, 5/5/79 2-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-2-2-3-10-13 1,1 Bad Luck, H Melvin, 2/15/75 12-4-2-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-2-2-3-4-5-5-7-10-15 4,15 Bang A Gong, Witch Queen, 3/10/79 12-11-9-8-15 -

1 "Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music S

"Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music Studies, 20, 3, 2008, 276-329 This story begins with a skinny white DJ mixing between the breaks of obscure Motown records with the ambidextrous intensity of an octopus on speed. It closes with the same man, debilitated and virtually blind, fumbling for gospel records as he spins up eternal hope in a fading dusk. In between Walter Gibbons worked as a cutting-edge discotheque DJ and remixer who, thanks to his pioneering reel-to-reel edits and contribution to the development of the twelve-inch single, revealed the immanent synergy that ran between the dance floor, the DJ booth and the recording studio. Gibbons started to mix between the breaks of disco and funk records around the same time DJ Kool Herc began to test the technique in the Bronx, and the disco spinner was as technically precise as Grandmaster Flash, even if the spinners directed their deft handiwork to differing ends. It would make sense, then, for Gibbons to be considered alongside these and other towering figures in the pantheon of turntablism, but he died in virtual anonymity in 1994, and his groundbreaking contribution to the intersecting arts of DJing and remixology has yet to register beyond disco aficionados.1 There is nothing mysterious about Gibbons's low profile. First, he operated in a culture that has been ridiculed and reviled since the "disco sucks" backlash peaked with the symbolic detonation of 40,000 disco records in the summer of 1979. -

Darude Sandstorm Download Mp3

1 / 2 Darude Sandstorm Download Mp3 Darude - Sandstorm download mp3 · Artist: Darude · Song: Sandstorm · Genre: Pop · Length: 07:03.. Download and print in PDF or MIDI free sheet music for Sandstorm by Darude ... The track was uploaded to MP3.com where it gained global recognition. Trance.. Darude - Sandstorm.mp3.meta · ambient sound, 3 months ago. Duck Toy Squeak Dog Toy Sound Effect (download)-[AudioTrimmer.com].mp3 · sounds .... I'm looking for some way to convert mp3 files into MML. Darude - Sandstorm MIDI Artist Darude: Title Sandstorm Free Download Play MIDI Stop MIDI: Convert .... Get all songs from Darude Sandstorm di Gold Mp3. Download a collection list of songs from Darude Sandstorm easily, free as much as you like, and enjoy!. Darude - Music mp3. Darude - Music Written & arranged by V. · Darude - Music (Original Version) (2003) mp3 · Darude - Sandstorm mp3 · Darude - Music mp3 ... Free Download Darude Sandstorm Marimba Remix Ringtone in high quality. You can download this ringtone in 2 formats:m4r for iPhone, mp3 for android.. Darude - Feel The Beat mp3 Duration 4:12 Size 9.61 MB / Darude 4. Download Darude Sandstorm MP3 Free. All Genres Balearic/Downtempo Bass Breakbeat .... coryxkenshin outro darude sandstorm (4.7 MB) mp3 download really free http://disq.us/t/29kfr1j. 10:54 PM - 22 Jun 2016. 0 replies 0 retweets 0 likes. Reply.. Darude Sandstorm (mp3 Download), 7SuperNova, 04:05, PT4M5S, 5.61 MB, 124902, 660, 43, 2008-10-11 08:44:04, 2021-03-26 00:34:27, Mp3 Lists, .... Addeddate: 2018-11-01 00:53:19. Identifier: whatisthemusictitle_201811. Scanner: Internet Archive HTML5 Uploader 1.6.3.