Final White-Tailed Deer Management Plan and Environmental Impact Statement Summer 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Md Cracker Barrel 2005.Pdf

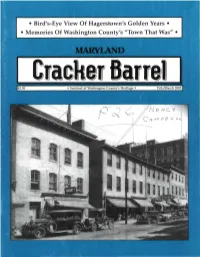

• Bird's-Eye View Of Hagerstown's Golden Years • • Memories Of Washington County's "Town That Was" • MARYLAND l$2.50 • Sentinel of Washington County's Heritage • Feb./March 2005 P oi C> H n H c V Meet Us at the Friendly MARYLAND Cracker Barrel Bi-Monthly! Gather around the pot-bellied stove Grader Bar rel and the checkerboard with a barrel of Our 33rd year common crackers within easy reach and Volume 33 -- No. 4 enjoy the Maryland Cracker Barrel. Since June of 1971 this magazine has Published bi-monthly by been a gathering place for folks interested MARYLAND CRACKER in preserving the heritage of Washington BARREL, INC. 7749 Fairplay Road County. Boonsboro, MD 21713-2322 It is our goal to present the story of the (301)582-3885 individuals who have striven to give this region a heritage worthy of preservation. Editor and Publisher Frank Woodring Associate Editor Suanne Woodring Attention: Former Fairchild Employees Chad Woodring This summer we plan to focus on Fairchild Aircraft in Washing Donald Dayhoff ton County. We would appreciate if you would submit your fa Janet Dayhoff vorite memory of your association with Fairchild by June 1. Fred Kuhn Please include your name, address, department, and number of Bonnie Kuhn years spent with Fairchild. Bob Waring Betty Waring Contributing Writers Coming Richard Clem Jessie Robinette Spring of 2005 Blair Williamson Order Prior to March 1 Printed by to Receive Oak Printing, Inc. Pre-Publication Special 952 Frederick Street Hagerstown, MD 21740 $19.99 (Includes Tax and Shipping) Subscription Rate: $13.65 per year Orders Received Maryland Cracker Barrel After March 1 7749 Fairplay Road $22.99 Boonsboro, MD 21713 301-582-3885 Maryland Cracker Barrel 7749 Fairplay Road [email protected] Boonsboro, MD 21713 Images of America 301-582-3885 FRONT COVER: The photo PEN MAR depicts the east side of the first Images of America, PEN MAR contains 128 pages with more than block of North Potomac Street 200 pictures of historic Pen Mar Park along with the Western in Hagerstown. -

Classification

F-687 Nov-08-2004 14:45 From-ANTI RM 4 LE 3014320313 T-911 P.002 / .. - UNITED STATtS DtPAjtTMHNTOFTHb INTtKIOR FOR NFS USE ONLY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ,ATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVED / INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS_____ NAME HISTORIC An tier am National Battlefield AND/OR COMMON " • • '• ' [LOCATION STREET ft NUMBER P. 0. Box 158 —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Sharsburg VICINITY OF Sixth STATE m " „ COUNTY Maryland B Washington CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE ^DISTRICT _PUBUC JKOCCUPIED JXAGRICULTUHE —MUSEUM —BUILDINGIS) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL JKPARK .STRUCTURE 2BOTH .WORK IN PROGRESS .EDUCATIONAL ^PRIVATE RESIDENCE ^.SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE .ENTERTAINMENT ^RELIGIOUS —OBJECT JCIN PROCESS _~YE5: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT ^SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED JSYES: UNRESTRICTED .INDUSTRIAL .TRANSPORTATION —MILITARY MOTHER: AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: i National Capital Beginn/Mat-'fonal Park STREET & NUMBER 1100 Ohio Drive, S.W. CITY. TOWN, . STATE Washington, D.C,_20242 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY Of DEEO&ETC. Waahingt(m County STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Hageretown, Maryland H REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Partial representation lo State Historic Sites Survey OATE .FEDERAL &STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Maryland Historic Trust, 21 State Circle CITY. TOWN STATE Awtapolls, Maryland Nov-08-Z004 14:45 From-ANT I RM & LE 3014320313 T-911 P.003/009 F-687 H DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT ^DETERIORATED _UN ALTER ED X.GOOO _RUINS JLALTERED —FAIR __UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL OF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Antietam National Battlefield is located near the Maryland hank, of the Potomac River and along Antietam Creek north and east of the village of Sharpsburg, Maryland. -

Winter Lights & Lore Media

Media Kit Table of Contents About the Heart of the Civil War Heritage Area ................................................................................. 3 About this Media Kit ......................................................................................................................... 4 Winter Lights & Lore: Selected Events ............................................................................................... 5 Memorial Illumination ................................................................................................................................5 Newcomer House Illumination ...................................................................................................................5 Captain Flagg’s US Quartermaster City, 1864: Prospects of Peace ................................................................5 Civil War Christmas in Shepherdstown ........................................................................................................6 Battle of Shepherdstown Illumination .........................................................................................................6 Civil War Encampment ...............................................................................................................................7 Traditional Village Christmas ......................................................................................................................7 While Visions of Sugar Plums Danced in Their Heads ...................................................................................7 -

America's Natural Nuclear Bunkers

America’s Natural Nuclear Bunkers 1 America’s Natural Nuclear Bunkers Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................... 10 Alabama .............................................................................................................. 12 Alabama Caves .................................................................................................. 13 Alabama Mines ................................................................................................. 16 Alabama Tunnels .............................................................................................. 16 Alaska ................................................................................................................. 18 Alaska Caves ..................................................................................................... 19 Alaska Mines ............................................................................................... 19 Arizona ............................................................................................................... 24 Arizona Caves ................................................................................................... 25 Arizona Mines ................................................................................................... 26 Arkansas ............................................................................................................ 28 Arkansas Caves ................................................................................................ -

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory Newcomer

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2012 Newcomer Farmstead Antietam National Battlefield Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information Newcomer Farmstead Antietam National Battlefield Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Purpose and Goals of the CLI The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI) is an evaluated inventory of all significant landscapes in units of the national park system in which the National Park Service has, or plans to acquire any enforceable legal interest. Landscapes documented through the CLI are those that individually meet criteria set forth in the National Register of Historic Places such as historic sites, historic designed landscapes, and historic vernacular landscapes or those that are contributing elements of properties that meet the criteria. In addition, landscapes that are managed as cultural resources because of law, policy, or decisions reached through the park planning process even though they do not meet the National Register criteria, are also included in the CLI. The CLI serves three major purposes. First, it provides the means to describe cultural landscapes on an individual or collective basis at the park, regional, or service-wide level. Secondly, it provides a platform to share information about cultural landscapes across programmatic areas and concerns and to integrate related data about these resources into park management. Thirdly, it provides an analytical tool to judge accomplishment and accountability. The legislative, regulatory, and policy direction for conducting the CLI include: National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (16 USC 470h-2(a)(1)). -

WA-II-1145 Keedysville Historic District

WA-II-1145 Keedysville Historic District Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 03-12-2004 NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct.1990) United States Department of the Interior -1tional Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "NIA" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. -

Porch Program” Series to Begin at Newcomer House in April

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Date: March 29, 2016 Contact: Rachel Nichols, Newcomer House Manager: [email protected] Web: www.heartofthecivilwar.org New “Porch Program” Series to Begin at Newcomer House in April Keedysville, MD – The Heart of the Civil War Heritage Area (HCWHA) will begin a new series of monthly public programs at the Newcomer House, HCWHA’s Exhibit & Visitor Center at Antietam National Battlefield, in April. These programs will be free and family-friendly, taking place on the porch of the historic house if weather permits. The first three programs of the 2016 season will cover diverse topics including music of the Civil War era, the role of women at Antietam, and fostering a love for history across generations. Programs taking place July-December are currently under development. April 23: Songs and Stories of the Civil War (11:00 AM, 1:30 PM & 4:00 PM) Through period songs, excerpts from actual letters, and anecdotes both humorous and poignant, Matthew Dodd takes listeners back in time to feel what it was like to be a soldier, civilian, loved-one-at-home or escaped slave in the Civil War era. Dodd will bypass the stories of the generals and the battle movements and concentrate on the feelings of individuals on the home front and seeking freedom. Dodd will play acoustic guitar, harmonica, banjo and mandolin in an informal, story circle setting. May 7: Women of Antietam (11:30 AM and 1:30 PM) Civil War medicine expert Betsy Estilow will discuss the role of nurses and other women at the September 1862 Battle of Antietam on the porch of the Newcomer House. -

BOARD of COUNTY COMMISSIONERS October 8, 2019 OPEN SESSION AGENDA 08:00 A.M. MOMENT of SILENCE and PLEDGE of ALLEGIANCE CALL TO

Wayne K. Keefer Jeffrey A. Cline, President Cort F. Meinelschmidt Terry L. Baker, Vice President Randall E. Wagner Krista L. Hart, Clerk 100 West Washington Street, Suite 1101 | Hagerstown, MD 21740-4735 | P: 240.313.2200 | F: 240.313.2201 WWW.WASHCO-MD.NET BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS October 8, 2019 OPEN SESSION AGENDA 08:00 A.M. MOMENT OF SILENCE AND PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE CALL TO ORDER, President Jeffrey A. Cline APPROVAL OF MINUTES – September 24, 2019 08:05 A.M. CLOSED SESSION (To discuss the appointment, employment, assignment, promotion, discipline, demotion, compensation, removal, resignation, or performance evaluation of appointees, employees, or officials over whom this public body has jurisdiction; or any other personnel matter that affects one or more specific individuals; To consider the acquisition of real property for a public purpose and matters directly related thereto; To consider a matter that concerns the proposal for a business or industrial organization to locate, expand, or remain in the State; To consult with counsel to obtain legal advice on a legal matter; & To consult with staff, consultants, or other individuals about pending or potential litigation; To discuss public security, if the public body determines that public discussion would constitute a risk to the public or to public security, including: (i) the development of fire and police services and staff; and (ii) the development and implementation of emergency plans.) 10:00 A.M. RECONVENE IN OPEN SESSION 10:05 A.M. COMMISSIONERS’ REPORTS AND COMMENTS 10:15 A.M. REPORTS FROM COUNTY STAFF 10:25 A.M. CITIZENS PARTICIPATION 10:30 A.M. -

SHEPHERDSTOWN BATTLEFIELD Special Resource Study / Boundary Study / National Park Service U.S

SHEPHERDSTOWN BATTLEFIELD SPECIAL RESOURCE STUDY / BOUNDARY STUDY / National Park Service ENVIRONMENTAL AssEssMENT U.S. Department of the Interior WEST VIRGINIA AND MARYLAND August 2014 U.S. Department of the Interior Shepherdstown Battlefield West Virginia and Maryland August 2014 Special Resource Study / Boundary Study / Environmental Assessment HOW TO COMMENT ON THIS STUDY Comments are welcome and will be accepted for a HAND DELIVERY: minimum of 30 days after this study is published and distributed. While comments may be submitted by any one Written and/or verbal comments may be made at public of the following methods commenters are encouraged to meetings. The dates, times, and locations of public use the Internet, if possible. meetings will be announced in the media and on the Planning, Environment, and Public Comment site (Web MAIL: address above) following release of this document. National Park Service Please submit only one set of comments. Denver Service Center – Planning Jordan Hoaglund, Project Manager Before including your address, telephone number, e-mail PO Box 25287 address, or other personal information in your comment, Denver, CO 80225-0287 you should be aware that your entire comment—including your personal identifying information—may be made ONLINE: publicly available at any time. Although you can ask us http://parkplanning.nps.gov/shba in your comment to withhold your personal identifying information from public review, we cannot guarantee that we will be able to do so. i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION The Department of the Interior, National Park Service study criteria to evaluate the suitability and feasibility (NPS), has prepared this special resource study / boundary of the addition. -

Keedysville Is a Rural Incorporated Municipality Located in the South Central Portion of Washington County in Western Maryland

KEEDYSVILLE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION Keedysville is a rural incorporated municipality located in the south central portion of Washington County in western Maryland. The Town is located approximately 30 miles from Chambersburg, Pennsylvania and Frederick, Maryland; and 60 miles from Washington and Baltimore. It is bisected by Maryland Route 34 which is a Minor Arterial roadway that connects the eastern and western part of southern Washington County and is the most direct route from Boonsboro to Sharpsburg, Maryland and the Antietam Battlefield. The Town is located in Election District 19 and in Washington County's Planning Sector II. The surrounding land in the County is part of the Hagerstown Valley which consists mainly of fertile Class I and II soils that support agricultural activities still in crops. However, there are some areas that have been developed into small residential subdivisions. Keedysville is located in the Antietam Creek watershed and does have some steep slopes, floodplain, and non-tidal wetlands associated with the Little Antietam Creek that the Town must consider when reviewing and approving development proposals. The Town of Keedysville shares a rich resource with Washington County and the State of Maryland due to its proximity to the Antietam National Battlefield. The Town's western boundary abuts one of the Antietam Battlefields' Overlay zones. A marker in the center of Town summarizes a battle that took place within the Town's boundaries; however, there is a larger piece of history reflected in several landmarks in Keedysville. The Little Antietam Creek runs through this quaint town and adds to its history and its beginning as a rural village in 1730. -

WA-II-1173 Keedysville Road and Historic Trace (Coffman Farms Rd,Braddock Rd,Rd to Conococheague)

WA-II-1173 Keedysville Road and Historic Trace (Coffman Farms Rd,Braddock Rd,Rd to Conococheague) Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 01-24-2012 Capsule Summary Inventory No.WA-II-1173 Keedysville Road and Historic Trace Keedysville Road Washington County, MD Ca. 1731, 1830 (Hitt Bridge), 1833 (new road section and Pry's Mill Bridge); 1862 Access: Public The Keedysville Road, one of the oldest roads in Washington County, was in use during the early settlement period of the 1730s. The narrow two-lane track was part of the historic road leading from Frederick, MD from the east to Williamsport, MD to the west. It connects to farther points from either end. -

The Douglas Hike- a Journey of Recollection Into Springtime - 1954 to 1994

C & 0 Canal Association concerned with the conservation of the natural and historical environment of the C & 0 Canal and the Poton1ac River Basin VOLUME XXVI JUNE 1994 NUMBER 2 The Douglas Hike- A Journey of Recollection Into Springtime - 1954 to 1994 THE PRESIDENTS COLUMN It was a journey of recollection, even a pilgrimage of sorts, Her favor, Mother Nature, late one day, singled out one ofus with stopovers at many of the campsites and sportsmen's for a drenching in a thunderous cloudburst. The chosen one clubs, where Douglas and his party spent nights on the way was Sue Ann Sullivan of Williamsport fame, arrayed in from Cumberland to Washington. It was a time of purple was she. Desperate, another hiker lept into a hiker reaffirming old and the making of new friendships. The two biker privy, another under a bridge. The rest of us were week trek was also a labor of love with blisters among its already esconsed in the welcoming shelter of the Kanawha visible tokens. It was a time of solitude and conversation Club, the day's destination. along the towpath, of festivity at evening meals and around the campfire. In any case, the spirit of our hiking troop was never dampened. A few examples will serve. Badly blistered feet Cathy Douglas Stone travelled all the way down from New did not deter Peggy Weber. Scarcely able to walk one day, Hampshire to give us an inspiring sendoff. Before cutting Peggy hopped on a bike to maintain momentum, but a bit the ribbon, she shared with us the following thought: "The unpracticed, she tipped over, dislocating her shoulder.