Methcognition: Taking the Information to the Front Lines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught up in You .38 Special Hold on Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught Up in You .38 Special Hold On Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down When You're Young 30 Seconds to Mars Attack 30 Seconds to Mars Closer to the Edge 30 Seconds to Mars The Kill 30 Seconds to Mars Kings and Queens 30 Seconds to Mars This is War 311 Amber 311 Beautiful Disaster 311 Down 4 Non Blondes What's Up? 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect The 88 Sons and Daughters a-ha Take on Me Abnormality Visions AC/DC Back in Black (Live) AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (Live) AC/DC Fire Your Guns (Live) AC/DC For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) (Live) AC/DC Heatseeker (Live) AC/DC Hell Ain't a Bad Place to Be (Live) AC/DC Hells Bells (Live) AC/DC Highway to Hell (Live) AC/DC The Jack (Live) AC/DC Moneytalks (Live) AC/DC Shoot to Thrill (Live) AC/DC T.N.T. (Live) AC/DC Thunderstruck (Live) AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie (Live) AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long (Live) Ace Frehley Outer Space Ace of Base The Sign The Acro-Brats Day Late, Dollar Short The Acro-Brats Hair Trigger Aerosmith Angel Aerosmith Back in the Saddle Aerosmith Crazy Aerosmith Cryin' Aerosmith Dream On (Live) Aerosmith Dude (Looks Like a Lady) Aerosmith Eat the Rich Aerosmith I Don't Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Janie's Got a Gun Aerosmith Legendary Child Aerosmith Livin' On the Edge Aerosmith Love in an Elevator Aerosmith Lover Alot Aerosmith Rag Doll Aerosmith Rats in the Cellar Aerosmith Seasons of Wither Aerosmith Sweet Emotion Aerosmith Toys in the Attic Aerosmith Train Kept A Rollin' Aerosmith Walk This Way AFI Beautiful Thieves AFI End Transmission AFI Girl's Not Grey AFI The Leaving Song, Pt. -

Green Day Singles Longplay

Chart - History Alle Hits aus Deutschland, Großbritannien und den USA Singles und Alben TOP 100 Green Day Singles Longplay Beste Pos. Titel Top 10 # 1 Beste Pos. Titel Top 10 # 1 6 141 --- 1 1 179 1 2 245 --- 1 4 158 3 2 92 --- 1 5 1510 3 Singles 1 Longview Jun 1994 30 2 Basket Case Mrz 1995 18 Aug 1994 7 3 Welcome To Paradise Okt 1994 20 4 When I Come Around Jun 1995 45 Mai 1995 27 5 Geek Stink Breath Okt 1995 73 Okt 1995 16 6 Stuck With Me Jan 1996 24 7 Brain Stew / Jaded Jul 1996 28 8 Hitchin' A Ride Okt 1997 25 9 Time Of Your Life (Good Riddance) Jan 1998 11 10 Redundant Mai 1998 27 11 Minority Sep 2000 18 12 Warning Dez 2000 27 13 Waiting Nov 2001 34 14 American Idiot Okt 2004 28 Sep 2004 3 Aug 2004 61 15 Boulevard Of Broken Dreams Jan 2005 13 Dez 2004 5 Nov 2004 2 16 Holiday Mai 2005 50 Mrz 2005 11 Apr 2005 19 17 Wake Me Up When September Ends Aug 2005 22 Jun 2005 8 Aug 2005 6 18 Jesus Of Suburbia Dez 2005 76 Nov 2005 17 19 The Saints Are Coming Nov 2006 6 Nov 2006 2 Dez 2006 51 als ► U 2 & Green Day 20 Working Class Hero Mai 2007 53 21 The Simpsons Theme Aug 2007 19 22 Know Your Enemy Mai 2009 14 Apr 2009 21 Mai 2009 28 23 21 Guns Aug 2009 13 Jul 2009 36 Jul 2009 22 24 21st Century Breakdown Nov 2009 71 25 Last Of The American Girls Jun 2010 45 26 When It's Time Jun 2010 68 27 Oh Love Aug 2012 44 Aug 2012 97 28 Bang Bang Aug 2016 84 Longplay 1 Dookie Okt 1994 4 Nov 1994 13 Mai 1994 2 2 Insomniac Okt 1995 12 Okt 1995 8 Okt 1995 2 3 Nimrod Okt 1997 31 Okt 1997 11 Nov 1997 10 4 Warning Okt 2000 21 Okt 2000 4 Okt 2000 4 Green Day Status: -

Read Kindle // Green Day -- Favorites to Strum and Sing: Easy Guitar Tab

YATVBCEXDE0I # Doc » Green Day -- Favorites to Strum and Sing: Easy Guitar Tab (Paperback) Green Day -- Favorites to Strum and Sing: Easy Guitar Tab (Paperback) Filesize: 2.09 MB Reviews It in one of the most popular book. I am quite late in start reading this one, but better then never. Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. (Camylle Larson) DISCLAIMER | DMCA Y3U7DOAM0M2F Book # Green Day -- Favorites to Strum and Sing: Easy Guitar Tab (Paperback) GREEN DAY -- FAVORITES TO STRUM AND SING: EASY GUITAR TAB (PAPERBACK) Alfred Music, United States, 2007. Paperback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book. Twenty-five of Green Day s greatest hits, arranged in an easy-to-use lyric and chord songbook format. All lyrics with the correct guitar chords placed above throughout. Plus, important ris are included in tablature as well. Titles include: American Idiot * Basket Case * Boulevard of Broken Dreams * Brain Stew * Geek Stink Breath * Good Riddance (Time of Your Life) * Hitchin a Ride * Holiday * Jaded * J.A.R. (Jason Andrew Relva) * Longview * Macy s Day Parade * Maria * Minority * Nice Guys Finish Last * Poprocks Coke * Redundant * She * Stuck with Me * Waiting * Wake Me Up When September Ends * Walking Contradiction * Warning * Welcome to Paradise * When I Come Around. Read Green Day -- Favorites to Strum and Sing: Easy Guitar Tab (Paperback) Online Download PDF Green Day -- Favorites to Strum and Sing: Easy Guitar Tab (Paperback) JXELPADEHJMS > eBook < Green Day -- Favorites to Strum and Sing: Easy Guitar Tab (Paperback) See Also The Snow Globe: Children s Book: (Value Tales) (Imagination) (Kid s Short Stories Collection) (a Bedtime Story) Createspace, United States, 2013. -

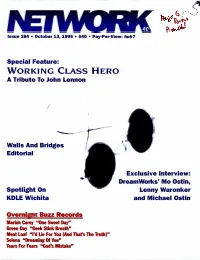

WORKING CLASS HERO a Tribute to John Lennon

Issue 284 October 13, 1995 $40 Pay -Per -View: huh? Special Feature: WORKING CLASS HERO A Tribute To John Lennon Walls And Bridges Editorial Exclusive Interview: DreamWorks' Mo Ostin, Spotlight On Lenny Waronker KDLE Wichita and Michael Ostin Overnight Buzz Records Mariah Carey "One Sweet Day" Green Day "Leek Stink Breath" Meat Loaf "I'd Lie For You (And That's The Truth)" Selena "Dreaming Of You" Tears For Fears "God's Mistake" St THE SILVER BULLET BAND IT'S A YSTERY IMPACT DATE OCTOBER 16 ii NEW'Rend STORIES) BY BOB SEGER FRO MANAG HEUNCH PREMIERE ANDREWS 1995 CAPITOL STORYTELLER. RECORDS. IN( #284 published by NETWORK 40 INC. 120 N. Wary RI., Burbank, CA 91502 phone (818) 9554040 fax (818) 9712420 [email protected] #1 Added #1 Accelerated #1 PPW JOE RICCITELLI RICK BISCEGLIA JERRY BLAIR MELISSA ETHERIDGE TLC MARIAN CAREY On The Cover: Most Requested 36 The cover art from the Working Class Hero album. A Network 40 exclusive: four pages of the hottest reaction records. News 4 Plugged In 44 Music video rotations at the major video channels. Page 6 not on page 6! The whole truths, the half-truths and anything but the truth.... Oh Wow! 46 Halloween Songs. Editorial 10 Programmers Textbook 48 VP/GM Gerry Cagle on "Walls And Bridges." Bill Richards on "The Alternative Angle." Special Feature: "A Pet Project" 12 Show Prep 50 The All -Star John Lennon Benefit Album Play It, Say It! / Trivia / Rimshots Exclusive: "A New Dream Team Gets To Work" ...16 Now Playing 52 Interview with Mo Ostin, Lenny Waronker and Michael Ostin. -

A Compartive Analysis of Five Songs from 1039/Smoothed out Slappy

A COMPARTIVE ANALYSIS OF FIVE SONGS FROM 1,039/SMOOTHED OUT SLAPPY HOURS AND 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN BY GREEN DAY _______________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of San Diego State University _______________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Music Theory _______________ by Alexandra Tea Summer 2011 iii Copyright © 2011 by Alexandra Tea All Rights Reserved iv DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my mother, Mei, and to my sister, Alexandrine, for providing a life time of love and support. v ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS A Comparative Analysis of Five Songs from 1,039/Smoothed Out Slappy Hours and 21st Century Breakdown by Green Day by Alexandra Tea Master of Arts in Music San Diego State University, 2011 Originating in Northern California’s underground punk scene more than two decades ago, Green Day became one of the first punk bands whose music effectively entered into the mainstream culture. Although Green Day’s biography has been documented in several books and the field of music analysis has expanded to include popular music, there has not yet been a detailed study of Green Day’s music. The purpose of this study is to critically analyze five songs from Green Day’s first album, 1,039 Smoothed Out Slappy Hours (1991) and five songs from their most recent album, 21st Century Breakdown (2009) to determine how the musical style of Green Day has changed over an eighteen year period. The study implements an adaptation of Jan LaRue’s Guidelines to Stylistic Analysis, which examines sound, harmony, melody, rhythm, growth, and text. -

Shoot It out 3 Doors Down Here Without You It's Not My Time

10 Years Ace Frehley Battle Lust Outer Space Now Is The Time (Ravenous) Shoot It Out The Acro-brats Day Late, Dollar Short 3 Doors Down Here Without You Aerosmith It's Not My Time Back in the Saddle Kryptonite Cryin' When I'm Gone Dream On When You're Young Dream On (Live) I Don't Want to Miss a Thing 30 Seconds to Mars Legendary Child Attack Love In An Elevator Closer to the Edge Lover Alot From Yesterday Sweet Emotion Kings and Queens Train Kept A Rollin' The Kill Uncle Salty This Is War Walk This Way Woman of the World 311 Amber AFI Beautiful Disaster Beautiful Thieves Down Dancing Through Sunday End Transmission 38 Special Girl's Not Grey Caught Up In You Love Like Winter Hold On Loosely Medicate Miss Murder 4 Non Blondes The Leaving Song, Pt. II What's Up The Missing Frame a-ha After the Burial Take on Me Aspiration Berzerker ABBA Cursing Akhenaten Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midni... My Frailty Pendulum Abnormality Your Troubles Will Cease and Fortune Wi... Visions Against Me! AC/DC New Wave Back in Black (Live) Stop! Big Gun Thrash Unreal Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (Live) Fire Your Guns (Live) Airbourne For Those About to Rock (We Salute You)... Runnin' Wild Heatseeker (Live) Too Much, Too Young, Too Fast Hell Ain't a Bad Place to Be (Live) Hells Bells (Live) Alanis Morissette High Voltage (Live) Head Over Feet Highway to Hell (Live) Ironic Jailbreak (Live) You Oughta Know Let Me Put My Love Into You Let There Be Rock (Live) Alice Cooper Moneytalks (Live) Billion Dollar Babies (Live) Shoot to Thrill (Live) Elected T.N.T. -

38 Special Hold on Loosely 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 88 Sons And

RockBand Karaoke List - www.tdavis.org/rockband/ .38 Special Captain Jack Coral Faith No More Hold On Loosely I Go to Extremes Dreaming of You Epic 3 Doors Down It's Still Rock and Roll To Me Counting Crows Midlife Crisis Kryptonite Miami 2017 (Seen the Lights Go Accidentally in Love We Care A Lot 88 Movin' Out (Anthony's Song) Crooked X Fall Out Boy Sons and Daughters My Life Nightmare Dance, Dance AC/DC Only the Good Die Young Cure Dead on Arrival Back in Black (Live) Piano Man Just Like Heaven Sugar, We're Goin' Down Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap Prelude/Angry Young Man Darius Rucker This Ain't A Scene, It's An Arms Fire Your Guns (Live) Pressure Alright (RB3 version) Tnks Fr th Mmrs For Those About to Rock (We Say Goodbye to Hollywood Darryl Worley Filter Heatseeker (Live) Scenes from an Italian Restaurant Awful Beautiful Life (RB3 version) Hey Man, Nice Shot Hell Ain't a Bad Place to Be (Live) She's Always a Woman David Bowie Flaming Lips Hells Bells (Live) The Entertainer Let's Dance Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots High Voltage (Live) The Stranger Space Oddity Fleetwood Mac Highway to Hell (Live) We Didn't Start the Fire Suffragette City Go Your Own Way Jailbreak (Live) You May Be Right Dealership Gold Dust Woman Let There Be Rock (Live) Billy Squier Database Corrupted Flyleaf Moneytalks (Live) Christmas Is the Time to Say I Death of the Cool I'm So Sick Shoot to Thrill (Live) Black Crowes Can't Let Go Foo Fighters T.N.T. -

Green Day: Rock Music and Class

GREEN DAY: ROCK MUSIC AND CLASS Olivia Roig A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of SELECT ONE: May 2016 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Esther Clinton Dalton Anthony Jones Jeremy Wallach © 2016 Olivia Roig All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor The pop punk band Green Day is a surprisingly interesting source for a discussion of class. Despite their working class background, and their massive successes with Dookie in 1994, and American Idiot in 2004, Green Day performs many middle class values in their song lyrics, stage shows, and interviews. Using Chris McDonald’s book Rush: Rock Music and the Middle Class as a template, this paper analyzes Green Day’s performance of class through theories about social class in North America. Throughout Green Day’s career, there is a noticeable tension between wanting to stick to their working class roots and acknowledging their sudden and unexpected thrust into an upper class economic standing. Yet, despite skipping a middle class standing economically, their song lyrics, stage shows, and interviews articulate many middle class values such as individualism, professionalism, and the middle class family. iv For Grace Roig v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my thesis committee, Professors Jeremy Wallach, Esther Clinton, and Dalton Jones for their help and comments. I would also like to thank my Dad, Bruce Roig, for his help and support. Last, but not least, I would like to thank the members of Green Day for 26 years of amazing music, without which this paper never could have been written. -

![Still Buffering 250: Green Day Published March 6Th, 2021 Listen Here at Themcelroy.Family [Theme Music Plays] Rileigh: Hello, An](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9846/still-buffering-250-green-day-published-march-6th-2021-listen-here-at-themcelroy-family-theme-music-plays-rileigh-hello-an-12419846.webp)

Still Buffering 250: Green Day Published March 6Th, 2021 Listen Here at Themcelroy.Family [Theme Music Plays] Rileigh: Hello, An

Still Buffering 250: Green Day Published March 6th, 2021 Listen here at themcelroy.family [theme music plays] Rileigh: Hello, and welcome to Still Buffering: a cross-generational guide to the culture that made us. I am Rileigh Smirl. Sydnee: I'm Sydnee McElroy. Teylor: And I'm Teylor Smirl. Rileigh: Is that the— that's the phrase, right? Sydnee: What? Teylor: What? Rileigh: Uh, I— it was coming— like, our tagline, it was coming out of my mouth before I realized what I was saying, and then halfway through I wondered if I was saying the right thing. It didn't feel right in my mouth, but that was right, right? Sydnee: [laughs] Teylor: Now I don't know! What did you say? Rileigh: It's a cro— it's a cross-generational guide to the— yes. Yes. Sydnee: Yes. Rileigh: Okay. Never mind. Sorry! [laughs] Sydnee: Oh no! Rileigh: It's just one of those things that, like, now it's in, like, my muscle memory, so it just kind of comes out. Sydnee: Yeah. Rileigh: It didn't feel right... but I suppose it's been a— Sydnee: I wasn't really listening to you. I was waiting for my turn to talk. [laughs] Rileigh: Okay, alright. Teylor: I was also preparing myself to say my own name, which is sometimes a task. So, you know. [laughs] Sydnee: Uh, we've hit the wall. Teylor: Who knows! [laughs] Sydnee: It appears we've hit the wall. Rileigh: Listen, it's been a long week. [laughs] Sydnee: It's been a long— Teylor: Yes. -

Green Day Maria Original Version Download Maria

green day maria original version download Maria. Bring in the head of the government The dog ate the document Somebody shot the president And no one knows where Maria went? Maria, Maria, Maria Where did you go? Be careful what you're offering Your breath lacks the conviction Drawing the line in the dirt Because the last decision Is no. She smashed the radio with the board of education Turn up the static left of the state of the nation. Turn up the flame, step on the gas Burning the flag at half mast She's a rebel's forgotten son An export of the revolution. Unreleased/Uncollected Songs. So, what songs have NOT been officially released in all/most of the world, either at all (i.e. they've only leaked, at most), only as B-sides through CD singles (any or all applicable countries), on compilations (such as the two Fat Wreck ones), or only as bonus tracks in any countries or through specific retailers (might overlap with all but the first category)? Aside from the entirety of Cigarettes and Valentines (supposedly a backup still exists), here's what I've got so far: "409 in Your Coffeemaker" (unmixed, "Basket Case" single) "Redundant" (Richard Dodd mix, CD singles) "DUI" (pulled from Shenanigans, only on promo copies) "Church on Sunday" (alternate mix, promo CD) "Favorite Son" (Rock Against Bush Vol. II, Japanese version of American Idiot, "21 Guns" CD and 7" singles in at least one region) "21st Century Breakdown" (demo version w/alternate lyrics - leaked?) "Last of the American Girls" (radio mix, released on CD single?) "Shoplifter" (CD single,