Floristic Regions of the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

California's Serpentine

CALIFORNIA'S SERPENTINE by Art Kruckeberg Serpentine Rock Traditional teaching in geology tells us that rocks Californians boast of their world-class tallest and can be divided into three major categories—igneous, oldest trees, highest mountain and deepest valley; but metamorphic, and sedimentary. The igneous rocks, that "book of records" can claim another first for the formed by cooling from molten rock called magma, state. California, a state with the richest geological are broadly classified as mafic or silicic depending tapestry on the continent, also has the largest exposures mainly on the amount of magnesium and iron or silica of serpentine rock in North America. Indeed, this present. Serpentine is called an ultramafic rock because unique and colorful rock, so abundantly distributed of the presence of unusually large amounts of around the state, is California's state rock. For magnesium and iron. Igneous rocks, particularly those botanists, the most dramatic attribute of serpentine is that originate within the earth's crust, above the its highly selective, demanding influence on plant life. mantle, contain small but significant amounts of The unique flora growing on serpentine in California illustrates the ecological truism that though regional climate controls overall plant distribution, regional Views of the classic serpentine areas at New Idria in San Benito County. The upper photo was taken in 1932, the lower in 1960 geology controls local plant diversity. Geology is used of the same view; no evident change in 28 years. Photos here in its broad sense to include land forms, rocks courtesy of the U.S. Forest Service and Dr. -

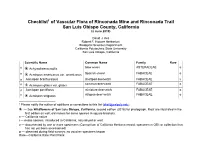

Rinconada Checklist-02Jun19

Checklist1 of Vascular Flora of Rinconada Mine and Rinconada Trail San Luis Obispo County, California (2 June 2019) David J. Keil Robert F. Hoover Herbarium Biological Sciences Department California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, California Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n ❀ Achyrachaena mollis blow wives ASTERACEAE o n ❀ Acmispon americanus var. americanus Spanish-clover FABACEAE o n Acmispon brachycarpus shortpod deervetch FABACEAE v n ❀ Acmispon glaber var. glaber common deerweed FABACEAE o n Acmispon parviflorus miniature deervetch FABACEAE o n ❀ Acmispon strigosus strigose deer-vetch FABACEAE o 1 Please notify the author of additions or corrections to this list ([email protected]). ❀ — See Wildflowers of San Luis Obispo, California, second edition (2018) for photograph. Most are illustrated in the first edition as well; old names for some species in square brackets. n — California native i — exotic species, introduced to California, naturalized or waif. v — documented by one or more specimens (Consortium of California Herbaria record; specimen in OBI; or collection that has not yet been accessioned) o — observed during field surveys; no voucher specimen known Rare—California Rare Plant Rank Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n Acmispon wrangelianus California deervetch FABACEAE v n ❀ Acourtia microcephala sacapelote ASTERACEAE o n ❀ Adelinia grandis Pacific hound's tongue BORAGINACEAE v n ❀ Adenostoma fasciculatum var. chamise ROSACEAE o fasciculatum n Adiantum jordanii California maidenhair fern PTERIDACEAE o n Agastache urticifolia nettle-leaved horsemint LAMIACEAE v n ❀ Agoseris grandiflora var. grandiflora large-flowered mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE v n Agoseris heterophylla var. cryptopleura annual mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE v n Agoseris heterophylla var. heterophylla annual mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE o i Aira caryophyllea silver hairgrass POACEAE o n Allium fimbriatum var. -

Vascular Flora of the Liebre Mountains, Western Transverse Ranges, California Steve Boyd Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 18 | Issue 2 Article 15 1999 Vascular flora of the Liebre Mountains, western Transverse Ranges, California Steve Boyd Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Boyd, Steve (1999) "Vascular flora of the Liebre Mountains, western Transverse Ranges, California," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 18: Iss. 2, Article 15. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol18/iss2/15 Aliso, 18(2), pp. 93-139 © 1999, by The Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, Claremont, CA 91711-3157 VASCULAR FLORA OF THE LIEBRE MOUNTAINS, WESTERN TRANSVERSE RANGES, CALIFORNIA STEVE BOYD Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden 1500 N. College Avenue Claremont, Calif. 91711 ABSTRACT The Liebre Mountains form a discrete unit of the Transverse Ranges of southern California. Geo graphically, the range is transitional to the San Gabriel Mountains, Inner Coast Ranges, Tehachapi Mountains, and Mojave Desert. A total of 1010 vascular plant taxa was recorded from the range, representing 104 families and 400 genera. The ratio of native vs. nonnative elements of the flora is 4:1, similar to that documented in other areas of cismontane southern California. The range is note worthy for the diversity of Quercus and oak-dominated vegetation. A total of 32 sensitive plant taxa (rare, threatened or endangered) was recorded from the range. Key words: Liebre Mountains, Transverse Ranges, southern California, flora, sensitive plants. INTRODUCTION belt and Peirson's (1935) handbook of trees and shrubs. Published documentation of the San Bernar The Transverse Ranges are one of southern Califor dino Mountains is little better, limited to Parish's nia's most prominent physiographic features. -

Sistemática Y Evolución De Encyclia Hook

·>- POSGRADO EN CIENCIAS ~ BIOLÓGICAS CICY ) Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, A.C. Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas SISTEMÁTICA Y EVOLUCIÓN DE ENCYCLIA HOOK. (ORCHIDACEAE: LAELIINAE), CON ÉNFASIS EN MEGAMÉXICO 111 Tesis que presenta CARLOS LUIS LEOPARDI VERDE En opción al título de DOCTOR EN CIENCIAS (Ciencias Biológicas: Opción Recursos Naturales) Mérida, Yucatán, México Abril 2014 ( 1 CENTRO DE INVESTIGACIÓN CIENTÍFICA DE YUCATÁN, A.C. POSGRADO EN CIENCIAS BIOLÓGICAS OSCJRA )0 f CENCIAS RECONOCIMIENTO S( JIOI ÚGIC A'- CICY Por medio de la presente, hago constar que el trabajo de tesis titulado "Sistemática y evo lución de Encyclia Hook. (Orchidaceae, Laeliinae), con énfasis en Megaméxico 111" fue realizado en los laboratorios de la Unidad de Recursos Naturales del Centro de Investiga ción Científica de Yucatán , A.C. bajo la dirección de los Drs. Germán Carnevali y Gustavo A. Romero, dentro de la opción Recursos Naturales, perteneciente al Programa de Pos grado en Ciencias Biológicas de este Centro. Atentamente, Coordinador de Docencia Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, A.C. Mérida, Yucatán, México; a 26 de marzo de 2014 DECLARACIÓN DE PROPIEDAD Declaro que la información contenida en la sección de Materiales y Métodos Experimentales, los Resultados y Discusión de este documento, proviene de las actividades de experimen tación realizadas durante el período que se me asignó para desarrollar mi trabajo de tesis, en las Unidades y Laboratorios del Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, A.C., y que a razón de lo anterior y en contraprestación de los servicios educativos o de apoyo que me fueron brindados, dicha información, en términos de la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor y la Ley de la Propiedad Industrial, le pertenece patrimonialmente a dicho Centro de Investigación. -

Federal Register / Vol. 61, No. 40 / Wednesday, February 28, 1996 / Proposed Rules

7596 Federal Register / Vol. 61, No. 40 / Wednesday, February 28, 1996 / Proposed Rules DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR appointment in the Regional Offices SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: listed below. Fish and Wildlife Service Information relating to particular taxa Background in this notice may be obtained from the The Endangered Species Act (Act) of 50 CFR Part 17 Service's Endangered Species 1973, as amended, (16 U.S.C. 1531 et Coordinator in the lead Regional Office seq.) requires the Service to identify Endangered and Threatened Wildlife identified for each taxon and listed species of wildlife and plants that are and Plants; Review of Plant and below: endangered or threatened, based on the Animal Taxa That Are Candidates for Region 1. California, Commonwealth best available scientific and commercial Listing as Endangered or Threatened of the Northern Mariana Islands, information. As part of the program to Species Hawaii, Idaho, Nevada, Oregon, Pacific accomplish this, the Service has AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Territories of the United States, and maintained a list of species regarded as Interior. Washington. candidates for listing. The Service maintains this list for a variety of ACTION: Notice of review. Regional Director (TE), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Eastside Federal reasons, includingÐto provide advance SUMMARY: In this notice the Fish and Complex, 911 N.E. 11th Avenue, knowledge of potential listings that Wildlife Service (Service) presents an Portland, Oregon 97232±4181 (503± could affect decisions of environmental updated list of plant and animal taxa 231±6131). planners and developers; to solicit input native to the United States that are Region 2. -

Theodore Payne Foundation, a Non-Profit Plant Nursery, Seed

Theodore Payne Foundation, a non-profit plant nursery, seed source, book store, and education center dedicated to the preservation of wild flowers and California native plants. This a report for May 15, 2015. New reports will be posted each Friday through the end of May. Believe it or not, rain and snow are in the forecast for the Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. Yes, that means chains may be required, so check before you go. And you will want to go, as the Western dogwood (Cornus nuttalli) is in full bloom in the Giant Forest or Grant Grove. Along highway 198 through Three Rivers and around the lower elevations of the park is another spectacular tree in full bloom now—the California buckeye (Aesculus californica). Look for Sierra monkeyflower (Mimulus aurantiacus), California flannel bush (Fremontodendron californicum) and elegant madia (Madia elegans) near Potwisha and Buckeye campgrounds as well. In the Santa Monica Mountains, hike the Dead Horse Loop Trail at Topanga Canyon State Park. From the Trippet Ranch Parking area go up the paved road that goes out from the northeast corner. Cross the bridge and turn left on the marked dirt trail. The trail starts with oak woodland to your left and a meadow to your right. At the meadow's edge there are blooming purple clarkia (Clarkia purpurea), sticky gum flower (Grindelia sp.), golden star lilies (Bloomeria crocea) and lots and lots of slender tarweed (Madia sp.). When the trail heads into the chaparral there is a floral explosion of black sage (Salvia mellifera), sticky monkey flower (Mimulus aurantiacus), woolly blue curls (Trichostema lanatum), honeysuckle (Lonicera sp.), deerweed (Acmispon glaber), elderberry (Sambucus nigra ssp. -

Networks in a Large-Scale Phylogenetic Analysis: Reconstructing Evolutionary History of Asparagales (Lilianae) Based on Four Plastid Genes

Networks in a Large-Scale Phylogenetic Analysis: Reconstructing Evolutionary History of Asparagales (Lilianae) Based on Four Plastid Genes Shichao Chen1., Dong-Kap Kim2., Mark W. Chase3, Joo-Hwan Kim4* 1 College of Life Science and Technology, Tongji University, Shanghai, China, 2 Division of Forest Resource Conservation, Korea National Arboretum, Pocheon, Gyeonggi- do, Korea, 3 Jodrell Laboratory, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, United Kingdom, 4 Department of Life Science, Gachon University, Seongnam, Gyeonggi-do, Korea Abstract Phylogenetic analysis aims to produce a bifurcating tree, which disregards conflicting signals and displays only those that are present in a large proportion of the data. However, any character (or tree) conflict in a dataset allows the exploration of support for various evolutionary hypotheses. Although data-display network approaches exist, biologists cannot easily and routinely use them to compute rooted phylogenetic networks on real datasets containing hundreds of taxa. Here, we constructed an original neighbour-net for a large dataset of Asparagales to highlight the aspects of the resulting network that will be important for interpreting phylogeny. The analyses were largely conducted with new data collected for the same loci as in previous studies, but from different species accessions and greater sampling in many cases than in published analyses. The network tree summarised the majority data pattern in the characters of plastid sequences before tree building, which largely confirmed the currently recognised phylogenetic relationships. Most conflicting signals are at the base of each group along the Asparagales backbone, which helps us to establish the expectancy and advance our understanding of some difficult taxa relationships and their phylogeny. -

South Coast and Montane Ecological Province

Vegetation Descriptions SOUTH COAST AND MONTANE ECOLOGICAL PROVINCE CALVEG ZONE 7 March 30, 2009 Note: This Province consists of the Southern California Mountains and Valleys Section or "Mountains" (M262B) and the Southern California Coast Section or "Coast" (262B) Note the slope gradients as follows: High gradient or steep (greater than 50%) Moderate gradient or moderately steep (30% to 50%) Low gradient (less than 30%) CONIFER FOREST / WOODLAND DM BIGCONE DOUGLAS-FIR ALLIANCE Bigcone Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga macrocarpa) - dominated stands are found in the Transverse and Peninsular Ranges from the Mt. Pinos region south. The Bigcone Douglas-fir Alliance is defined by the clear dominance of this species among competing conifers. It has been mapped sparsely in four subsections in the Coast Section, and infrequently in seven subsections and abundantly in four subsections of the Mountains Section. These pure conifer or mixed conifer and hardwood stands occur at lower elevations, generally in the range 1400 – 5600 ft (426 - 1708 m) in the Coast Section and up to about 7000 ft (2135 m) in the Mountains Section. Although mature individuals are capable of sprouting from branches and boles after burning, intense or frequently repeated fires and drought cycles will tend to eliminate this conifer. However, Bigcone Douglas-fir may become locally dominant with Canyon Live Oak (Quercus chrysolepis) as an associated tree on protected mesic canyon slopes, but not at the highest elevations. Sites in this Alliance are usually north facing at lower elevations and south-facing or steeper slopes at upper elevations. Shrub associates commonly include species of Ceanothus, Birchleaf Mountain Mahogany (Cercocarpus betuloides), California Buckwheat (Eriogonum fasciculatum), Chamise (Adenostoma fasciculatum), and shrub forms of the Live Oaks (Quercus spp.). -

Outline of Quino Recovery Plan

DRAFT RECOVERY PLAN FOR DEINANDRA CONJUGENS (OTAY TARPLANT) December 2003 Region 1 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Portland, Oregon Approved: XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Manager, California/Nevada Operations Office Region 1, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Date: ____________________________________________ DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate actions required to recover and protect federally listed plant and animal species. We (the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) publish recovery plans, sometimes preparing them with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and other affected and interested parties. Recovery teams serve as independent advisors to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Draft recovery plans are published for public review and submitted to scientific peer review before we adopt them. Objectives of the recovery plan will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not obligate other parties to undertake specific recovery actions and do not necessarily represent the view, official position, or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formation other than our own. They represent our official position only after they have been signed by the Director, Regional Director, or California/Nevada Operations Manager as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as directed by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery actions. Literature Citation should read as follows: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2003. Draft Recovery Plan for Deinandra conjugens (Otay Tarplant). Portland, Oregon. xi + 51 pp. An electronic version of this recovery plan will also be made available at http://pacific.fws.gov/ecoservices/endangered/recovery/default.htm and at http://endangered.fws.gov/recovery/index.html#plans. -

Draft Vegetation Communities of San Diego County

DRAFT VEGETATION COMMUNITIES OF SAN DIEGO COUNTY Based on “Preliminary Descriptions of the Terrestrial Natural Communities of California” prepared by Robert F. Holland, Ph.D. for State of California, The Resources Agency, Department of Fish and Game (October 1986) Codes revised by Thomas Oberbauer (February 1996) Revised and expanded by Meghan Kelly (August 2006) Further revised and reorganized by Jeremy Buegge (March 2008) March 2008 Suggested citation: Oberbauer, Thomas, Meghan Kelly, and Jeremy Buegge. March 2008. Draft Vegetation Communities of San Diego County. Based on “Preliminary Descriptions of the Terrestrial Natural Communities of California”, Robert F. Holland, Ph.D., October 1986. March 2008 Draft Vegetation Communities of San Diego County Introduction San Diego’s vegetation communities owe their diversity to the wide range of soil and climatic conditions found in the County. The County encompasses desert, mountainous and coastal conditions over a wide range of elevation, precipitation and temperature changes. These conditions provide niches for endemic species and a wide range of vegetation communities. San Diego County is home to over 200 plant and animal species that are federally listed as rare, endangered, or threatened. The preservation of this diversity of species and habitats is important for the health of ecosystem functions, and their economic and intrinsic values. In order to effectively classify the wide variety of vegetation communities found here, the framework developed by Robert Holland in 1986 has been added to and customized for San Diego County. To supplement the original Holland Code, additions were made by Thomas Oberbauer in 1996 to account for unique habitats found in San Diego and to account for artificial habitat features (i.e., 10,000 series). -

Santa Cruz Island Vegetation Confined to the Eastern 10% of Santa Cruz Island

. C HANNEL I SLANDS N ATIONAL P ARK . F INAL E NVIRONMENTAL I MPACT STATEMENT SANTA CRUZ ISLAND PRIMARY RESTORATION PLAN CHAPTER THREE AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT § Cultural Resources Introduction § Human Uses and Values For the most part, geologic and This chapter focuses on portions of the climatological conditions, processes, and environment that are directly related to disturbances cannot be altered by management conditions addressed in the alternatives. The activities. Watershed, soil, and atmospheric description of the affected environment is not conditions and processes, also part of the meant to be a complete description of the project physiographic setting, can be modified by area. Rather, it is intended to portray the certain management activities, and such impacts significant conditions and trends of the resources are outlined in Chapter Four, Environmental that may be affected by the proposed project or Consequences. its alternatives. Information in this chapter is based primarily on inventory and monitoring data from the Park’s resource management staff, information provided by The Nature Conservancy, U.S. Fish and Wildlife draft Physical Environment recovery plan for 13 plant taxa of the northern channel islands, independent academic research studies, and studies conducted as part of this proposed action. Other sources are noted where Setting applicable. Off the coast of southern California, eight This chapter is organized into four sections, ridges in the continental shelf rise above sea which when taken together provide the most level, forming a series of islands. The four complete description of the island resources, northern islands are located in the Santa Barbara including the human element. The four major Channel parallel to the coast south of Point components of this chapter are: Conception; the four southern islands are § Physical Environment scattered offshore between Los Angeles and the Mexican border. -

Flora-Lab-Manual.Pdf

LabLab MManualanual ttoo tthehe Jane Mygatt Juliana Medeiros Flora of New Mexico Lab Manual to the Flora of New Mexico Jane Mygatt Juliana Medeiros University of New Mexico Herbarium Museum of Southwestern Biology MSC03 2020 1 University of New Mexico Albuquerque, NM, USA 87131-0001 October 2009 Contents page Introduction VI Acknowledgments VI Seed Plant Phylogeny 1 Timeline for the Evolution of Seed Plants 2 Non-fl owering Seed Plants 3 Order Gnetales Ephedraceae 4 Order (ungrouped) The Conifers Cupressaceae 5 Pinaceae 8 Field Trips 13 Sandia Crest 14 Las Huertas Canyon 20 Sevilleta 24 West Mesa 30 Rio Grande Bosque 34 Flowering Seed Plants- The Monocots 40 Order Alistmatales Lemnaceae 41 Order Asparagales Iridaceae 42 Orchidaceae 43 Order Commelinales Commelinaceae 45 Order Liliales Liliaceae 46 Order Poales Cyperaceae 47 Juncaceae 49 Poaceae 50 Typhaceae 53 Flowering Seed Plants- The Eudicots 54 Order (ungrouped) Nymphaeaceae 55 Order Proteales Platanaceae 56 Order Ranunculales Berberidaceae 57 Papaveraceae 58 Ranunculaceae 59 III page Core Eudicots 61 Saxifragales Crassulaceae 62 Saxifragaceae 63 Rosids Order Zygophyllales Zygophyllaceae 64 Rosid I Order Cucurbitales Cucurbitaceae 65 Order Fabales Fabaceae 66 Order Fagales Betulaceae 69 Fagaceae 70 Juglandaceae 71 Order Malpighiales Euphorbiaceae 72 Linaceae 73 Salicaceae 74 Violaceae 75 Order Rosales Elaeagnaceae 76 Rosaceae 77 Ulmaceae 81 Rosid II Order Brassicales Brassicaceae 82 Capparaceae 84 Order Geraniales Geraniaceae 85 Order Malvales Malvaceae 86 Order Myrtales Onagraceae