An Examination of Algal Morphology and Toxicity Through Experiential Learning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Red Algae (Bangia Atropurpurea) Ecological Risk Screening Summary

Red Algae (Bangia atropurpurea) Ecological Risk Screening Summary U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, February 2014 Revised, March 2016, September 2017, October 2017 Web Version, 6/25/2018 1 Native Range and Status in the United States Native Range From NOAA and USGS (2016): “Bangia atropurpurea has a widespread amphi-Atlantic range, which includes the Atlantic coast of North America […]” Status in the United States From Mills et al. (1991): “This filamentous red alga native to the Atlantic Coast was observed in Lake Erie in 1964 (Lin and Blum 1977). After this sighting, records for Lake Ontario (Damann 1979), Lake Michigan (Weik 1977), Lake Simcoe (Jackson 1985) and Lake Huron (Sheath 1987) were reported. It has become a major species of the littoral flora of these lakes, generally occupying the littoral zone with Cladophora and Ulothrix (Blum 1982). Earliest records of this algae in the basin, however, go back to the 1940s when Smith and Moyle (1944) found the alga in Lake Superior tributaries. Matthews (1932) found the alga in Quaker Run in the Allegheny drainage basin. Smith and 1 Moyle’s records must have not resulted in spreading populations since the alga was not known in Lake Superior as of 1987. Kishler and Taft (1970) were the most recent workers to refer to the records of Smith and Moyle (1944) and Matthews (1932).” From NOAA and USGS (2016): “Established where recorded except in Lake Superior. The distribution in Lake Simcoe is limited (Jackson 1985).” From Kipp et al. (2017): “Bangia atropurpurea was first recorded from Lake Erie in 1964. During the 1960s–1980s, it was recorded from Lake Huron, Lake Michigan, Lake Ontario, and Lake Simcoe (part of the Lake Ontario drainage). -

A Review of Reported Seaweed Diseases and Pests in Aquaculture in Asia

UHI Research Database pdf download summary A review of reported seaweed diseases and pests in aquaculture in Asia Ward, Georgia; Faisan, Joseph; Cottier-Cook, Elizabeth; Gachon, Claire; Hurtado, Anicia; Lim, Phaik-Eem; Matoju, Ivy; Msuya, Flower; Bass, David; Brodie, Juliet Published in: Journal of the World Aquaculture Society Publication date: 2019 The re-use license for this item is: CC BY The Document Version you have downloaded here is: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record The final published version is available direct from the publisher website at: 10.1111/jwas.12649 Link to author version on UHI Research Database Citation for published version (APA): Ward, G., Faisan, J., Cottier-Cook, E., Gachon, C., Hurtado, A., Lim, P-E., Matoju, I., Msuya, F., Bass, D., & Brodie, J. (2019). A review of reported seaweed diseases and pests in aquaculture in Asia. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society, [12649]. https://doi.org/10.1111/jwas.12649 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights: 1) Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the UHI Research Database for the purpose of private study or research. 2) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 3) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Algae & Marine Plants of Point Reyes

Algae & Marine Plants of Point Reyes Green Algae or Chlorophyta Genus/Species Common Name Acrosiphonia coalita Green rope, Tangled weed Blidingia minima Blidingia minima var. vexata Dwarf sea hair Bryopsis corticulans Cladophora columbiana Green tuft alga Codium fragile subsp. californicum Sea staghorn Codium setchellii Smooth spongy cushion, Green spongy cushion Trentepohlia aurea Ulva californica Ulva fenestrata Sea lettuce Ulva intestinalis Sea hair, Sea lettuce, Gutweed, Grass kelp Ulva linza Ulva taeniata Urospora sp. Brown Algae or Ochrophyta Genus/Species Common Name Alaria marginata Ribbon kelp, Winged kelp Analipus japonicus Fir branch seaweed, Sea fir Coilodesme californica Dactylosiphon bullosus Desmarestia herbacea Desmarestia latifrons Egregia menziesii Feather boa Fucus distichus Bladderwrack, Rockweed Haplogloia andersonii Anderson's gooey brown Laminaria setchellii Southern stiff-stiped kelp Laminaria sinclairii Leathesia marina Sea cauliflower Melanosiphon intestinalis Twisted sea tubes Nereocystis luetkeana Bull kelp, Bullwhip kelp, Bladder wrack, Edible kelp, Ribbon kelp Pelvetiopsis limitata Petalonia fascia False kelp Petrospongium rugosum Phaeostrophion irregulare Sand-scoured false kelp Pterygophora californica Woody-stemmed kelp, Stalked kelp, Walking kelp Ralfsia sp. Silvetia compressa Rockweed Stephanocystis osmundacea Page 1 of 4 Red Algae or Rhodophyta Genus/Species Common Name Ahnfeltia fastigiata Bushy Ahnfelt's seaweed Ahnfeltiopsis linearis Anisocladella pacifica Bangia sp. Bossiella dichotoma Bossiella -

Characterization and Expression Profiles of Small Heat Shock Proteins in the Marine Red Alga Pyropia Yezoensis

Title Characterization and expression profiles of small heat shock proteins in the marine red alga Pyropia yezoensis Author(s) Uji, Toshiki; Gondaira, Yohei; Fukuda, Satoru; Mizuta, Hiroyuki; Saga, Naotsune Cell Stress and Chaperones, 24(1), 223-233 Citation https://doi.org/10.1007/s12192-018-00959-9 Issue Date 2019-01 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/76496 This is a post-peer-review, pre-copyedit version of an article published in Cell Stress and Chaperones. The final Rights authenticated version is available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12192-018-00959-9 Type article (author version) File Information manuscript-revised2018.12.13.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP Characterization and expression profiles of small heat shock proteins in the marine red alga Pyropia yezoensis Toshiki Uji1·Yohei Gondaira1·Satoru Fukuda2·Hiroyuki Mizuta1·Naotsune Saga2 1 Division of Marine Life Science, Faculty of Fisheries Sciences, Hokkaido University, Hakodate 041-8611, Japan 2 Section of Food Sciences, Institute for Regional Innovation, Hirosaki University, Aomori, Aomori 038-0012, Japan Corresponding author: Toshiki Uji Faculty of Fisheries Sciences, Hokkaido University, Hakodate 041-8611, Japan Tel/Fax: +81-138-40-8864 E-mail: [email protected] Running title: Transcriptional profiling of small heat shock proteins in Pyropia 1 Abstract Small heat shock proteins (sHSPs) are found in all three domains of life (Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya) and play a critical role in protecting organisms from a range of environmental stresses. However, little is known about their physiological functions in red algae. -

Seasonal and Interannual Changes in Ciliate and Dinoflagellate

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 07 February 2017 doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00016 Seasonal and Interannual Changes in Ciliate and Dinoflagellate Species Assemblages in the Arctic Ocean (Amundsen Gulf, Beaufort Sea, Canada) Edited by: Deo F. L. Onda 1, 2, 3, Emmanuelle Medrinal 1, 3, André M. Comeau 1, 3 †, Mary Thaler 1, 2, 3, George S. Bullerjahn, Marcel Babin 1, 2 and Connie Lovejoy 1, 2, 3* Bowling Green State University, USA Reviewed by: 1 Département de Biologie and Québec-Océan, Université Laval, Quebec, QC, Canada, 2 Takuvik, Joint International Rebecca Gast, Laboratory, UMI 3376, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS, France) and Université Laval, Québec, QC, Woods Hole Oceanographic Canada, 3 Institut de Biologie Intégrative et des Systèmes, Université Laval, Quebec, QC, Canada Institution, USA Alison Clare Cleary, Independent Researcher, San Recent studies have focused on how climate change could drive changes in Francisco, United States phytoplankton communities in the Arctic. In contrast, ciliates and dinoflagellates that can *Correspondence: contribute substantially to the mortality of phytoplankton have received less attention. Connie Lovejoy Some dinoflagellate and ciliate species can also contribute to net photosynthesis, [email protected] which suggests that species composition could reflect food web complexity. To identify †Present Address: André M. Comeau, potential seasonal and annual species occurrence patterns and to link species with Centre for Comparative Genomics and environmental conditions, we first examined the seasonal pattern of microzooplankton Evolutionary Bioinformatics-Integrated Microbiome Resource, Department of and then performed an in-depth analysis of interannual species variability. We used Pharmacology, Dalhousie University, high-throughput amplicon sequencing to identify ciliates and dinoflagellates to the lowest Canada taxonomic level using a curated Arctic 18S rRNA gene database. -

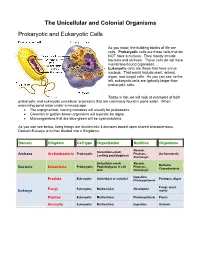

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic And

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells As you know, the building blocks of life are cells. Prokaryotic cells are those cells that do NOT have a nucleus. They mostly include bacteria and archaea. These cells do not have membrane-bound organelles. Eukaryotic cells are those that have a true nucleus. That would include plant, animal, algae, and fungal cells. As you can see, to the left, eukaryotic cells are typically larger than prokaryotic cells. Today in lab, we will look at examples of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic unicellular organisms that are commonly found in pond water. When examining pond water under a microscope… The unpigmented, moving microbes will usually be protozoans. Greenish or golden-brown organisms will typically be algae. Microorganisms that are blue-green will be cyanobacteria. As you can see below, living things are divided into 3 domains based upon shared characteristics. Domain Eukarya is further divided into 4 Kingdoms. Domain Kingdom Cell type Organization Nutrition Organisms Absorb, Unicellular-small; Prokaryotic Photsyn., Archaeacteria Archaea Archaebacteria Lacking peptidoglycan Chemosyn. Unicellular-small; Absorb, Bacteria, Prokaryotic Peptidoglycan in cell Photsyn., Bacteria Eubacteria Cyanobacteria wall Chemosyn. Ingestion, Eukaryotic Unicellular or colonial Protozoa, Algae Protista Photosynthesis Fungi, yeast, Fungi Eukaryotic Multicellular Absorption Eukarya molds Plantae Eukaryotic Multicellular Photosynthesis Plants Animalia Eukaryotic Multicellular Ingestion Animals Prokaryotic Organisms – the archaea, non-photosynthetic bacteria, and cyanobacteria Archaea - Microorganisms that resemble bacteria, but are different from them in certain aspects. Archaea cell walls do not include the macromolecule peptidoglycan, which is always found in the cell walls of bacteria. Archaea usually live in extreme, often very hot or salty environments, such as hot mineral springs or deep-sea hydrothermal vents. -

Coral Reef Algae

Coral Reef Algae Peggy Fong and Valerie J. Paul Abstract Benthic macroalgae, or “seaweeds,” are key mem- 1 Importance of Coral Reef Algae bers of coral reef communities that provide vital ecological functions such as stabilization of reef structure, production Coral reefs are one of the most diverse and productive eco- of tropical sands, nutrient retention and recycling, primary systems on the planet, forming heterogeneous habitats that production, and trophic support. Macroalgae of an astonish- serve as important sources of primary production within ing range of diversity, abundance, and morphological form provide these equally diverse ecological functions. Marine tropical marine environments (Odum and Odum 1955; macroalgae are a functional rather than phylogenetic group Connell 1978). Coral reefs are located along the coastlines of comprised of members from two Kingdoms and at least over 100 countries and provide a variety of ecosystem goods four major Phyla. Structurally, coral reef macroalgae range and services. Reefs serve as a major food source for many from simple chains of prokaryotic cells to upright vine-like developing nations, provide barriers to high wave action that rockweeds with complex internal structures analogous to buffer coastlines and beaches from erosion, and supply an vascular plants. There is abundant evidence that the his- important revenue base for local economies through fishing torical state of coral reef algal communities was dominance and recreational activities (Odgen 1997). by encrusting and turf-forming macroalgae, yet over the Benthic algae are key members of coral reef communities last few decades upright and more fleshy macroalgae have (Fig. 1) that provide vital ecological functions such as stabili- proliferated across all areas and zones of reefs with increas- zation of reef structure, production of tropical sands, nutrient ing frequency and abundance. -

JUDD W.S. Et. Al. (2002) Plant Systematics: a Phylogenetic Approach. Chapter 7. an Overview of Green

UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS An Overview of Green Plant Phylogeny he word plant is commonly used to refer to any auto- trophic eukaryotic organism capable of converting light energy into chemical energy via the process of photosynthe- sis. More specifically, these organisms produce carbohydrates from carbon dioxide and water in the presence of chlorophyll inside of organelles called chloroplasts. Sometimes the term plant is extended to include autotrophic prokaryotic forms, especially the (eu)bacterial lineage known as the cyanobacteria (or blue- green algae). Many traditional botany textbooks even include the fungi, which differ dramatically in being heterotrophic eukaryotic organisms that enzymatically break down living or dead organic material and then absorb the simpler products. Fungi appear to be more closely related to animals, another lineage of heterotrophs characterized by eating other organisms and digesting them inter- nally. In this chapter we first briefly discuss the origin and evolution of several separately evolved plant lineages, both to acquaint you with these important branches of the tree of life and to help put the green plant lineage in broad phylogenetic perspective. We then focus attention on the evolution of green plants, emphasizing sev- eral critical transitions. Specifically, we concentrate on the origins of land plants (embryophytes), of vascular plants (tracheophytes), of 1 UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS 2 CHAPTER SEVEN seed plants (spermatophytes), and of flowering plants dons.” In some cases it is possible to abandon such (angiosperms). names entirely, but in others it is tempting to retain Although knowledge of fossil plants is critical to a them, either as common names for certain forms of orga- deep understanding of each of these shifts and some key nization (e.g., the “bryophytic” life cycle), or to refer to a fossils are mentioned, much of our discussion focuses on clade (e.g., applying “gymnosperms” to a hypothesized extant groups. -

Lateral Gene Transfer of Anion-Conducting Channelrhodopsins Between Green Algae and Giant Viruses

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.15.042127; this version posted April 23, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 5 Lateral gene transfer of anion-conducting channelrhodopsins between green algae and giant viruses Andrey Rozenberg 1,5, Johannes Oppermann 2,5, Jonas Wietek 2,3, Rodrigo Gaston Fernandez Lahore 2, Ruth-Anne Sandaa 4, Gunnar Bratbak 4, Peter Hegemann 2,6, and Oded 10 Béjà 1,6 1Faculty of Biology, Technion - Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa 32000, Israel. 2Institute for Biology, Experimental Biophysics, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Invalidenstraße 42, Berlin 10115, Germany. 3Present address: Department of Neurobiology, Weizmann 15 Institute of Science, Rehovot 7610001, Israel. 4Department of Biological Sciences, University of Bergen, N-5020 Bergen, Norway. 5These authors contributed equally: Andrey Rozenberg, Johannes Oppermann. 6These authors jointly supervised this work: Peter Hegemann, Oded Béjà. e-mail: [email protected] ; [email protected] 20 ABSTRACT Channelrhodopsins (ChRs) are algal light-gated ion channels widely used as optogenetic tools for manipulating neuronal activity 1,2. Four ChR families are currently known. Green algal 3–5 and cryptophyte 6 cation-conducting ChRs (CCRs), cryptophyte anion-conducting ChRs (ACRs) 7, and the MerMAID ChRs 8. Here we 25 report the discovery of a new family of phylogenetically distinct ChRs encoded by marine giant viruses and acquired from their unicellular green algal prasinophyte hosts. -

Phytoref: a Reference Database of the Plastidial 16S Rrna Gene of Photosynthetic Eukaryotes with Curated Taxonomy

Molecular Ecology Resources (2015) 15, 1435–1445 doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12401 PhytoREF: a reference database of the plastidial 16S rRNA gene of photosynthetic eukaryotes with curated taxonomy JOHAN DECELLE,*† SARAH ROMAC,*† ROWENA F. STERN,‡ EL MAHDI BENDIF,§ ADRIANA ZINGONE,¶ STEPHANE AUDIC,*† MICHAEL D. GUIRY,** LAURE GUILLOU,*† DESIRE TESSIER,††‡‡ FLORENCE LE GALL,*† PRISCILLIA GOURVIL,*† ADRIANA L. DOS SANTOS,*† IAN PROBERT,*† DANIEL VAULOT,*† COLOMBAN DE VARGAS*† and RICHARD CHRISTEN††‡‡ *UMR 7144 - Sorbonne Universites, UPMC Univ Paris 06, Station Biologique de Roscoff, Roscoff 29680, France, †CNRS, UMR 7144, Station Biologique de Roscoff, Roscoff 29680, France, ‡Sir Alister Hardy Foundation for Ocean Science, The Laboratory, Citadel Hill, Plymouth PL1 2PB, UK, §Marine Biological Association, The Laboratory, Citadel Hill, Plymouth PL1 2PB, UK, ¶Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn, Villa Comunale, Naples 80121, Italy, **The AlgaeBase Foundation, c/o Ryan Institute, National University of Ireland, University Road, Galway Ireland, ††CNRS, UMR 7138, Systematique Adaptation Evolution, Parc Valrose, BP71, Nice F06108, France, ‡‡Universite de Nice-Sophia Antipolis, UMR 7138, Systematique Adaptation Evolution, Parc Valrose, BP71, Nice F06108, France Abstract Photosynthetic eukaryotes have a critical role as the main producers in most ecosystems of the biosphere. The ongo- ing environmental metabarcoding revolution opens the perspective for holistic ecosystems biological studies of these organisms, in particular the unicellular microalgae that -

I Biology I Lecture Outline 9 Kingdom Protista

I Biology I Lecture Outline 9 Kingdom Protista References (Textbook - pages 373-392, Lab Manual - pages 95-115) Major Characteristics Algae 1. Cbaracteristics 2. Classification 3. Division Cblorophyta 4. Division Chrysophyta 5. Division Phaeopbyta 6. Division Rhodopbyta Protozoans 1. Characteristics 2. Classification 3. Class FlageUata 4. Class Sarcodina 5. Class Ciliata 6. Class Sporozoa I Biology I Lecture Notes 9 Kingdom Protista References (Textbook - pages 373-392, Lab Manual- pages 95-115) Major Characteristics I. Protists possess eukaryotic cells with well defined nuclei and organelles 2. Most are unicellular, however there are multi-cellularforms 3. They are diverse in their structure 4. They vary in size from microscope algae to kelp that can be over 100feet in length 5. They are diverse (like bacteria) in the way they meet their nutritional needs A . Some are photosynthetic like land plants - are autotrophic B. Some ingest theirfood like animals - heterotrophic by ingestion C. Some absorb theirfood like bacteria andfungi - heterotrophic by absorption D. One species - Euglena - is mixotrophic meaning that it is capable ofboth autotrophic and heterotrophic life styles. 6. Reproduction in Protists A. is usually asexual by mitosis B. sexual reproduction involves meiosis and spore formation and usualJy occurs only when environmental conditions are hostile C. spores are resistant and can withstand adverse conditions 7. Some protozoans form cysts - a type ofresting stage 8. Photosynthetic protists (mostly algae) are part ofplankton. Plankton are those organisms suspended infresh and marine waters that serve asfood for -- heterotrophic animals and other protists 9. There are diverse opinions on how to classify members ofthe Kingdom Protista. -

The Origin and Evolution of Model Organisms

REVIEWS THE ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF MODEL ORGANISMS S. Blair Hedges The phylogeny and timescale of life are becoming better understood as the analysis of genomic data from model organisms continues to grow. As a result, discoveries are being made about the early history of life and the origin and development of complex multicellular life. This emerging comparative framework and the emphasis on historical patterns is helping to bridge barriers among organism-based research communities. Model organisms represent only a small fraction of the these species are receiving an unusually large amount of biodiversity that exists on Earth, although the research attention from the research community and fall under that has resulted from their study forms the core of bio- the broad definition of “model organism”. logical knowledge. Historically, research communities Knowledge of the relationships and times of origin of — often in isolation from one another — have focused these species can have a profound effect on diverse areas on these model organisms to gain an insight into the of research2. For example, identifying the closest relatives general principles that underlie various disciplines, such of a disease vector will help to decipher unique traits — as genetics, development and evolution. This has such as single-nucleotide polymorphisms — that might changed in recent years with the availability of complete contribute to a disease phenotype. Similarly, knowing genome sequences from many model organisms, which that our closest relative is the chimpanzee is crucial for has greatly facilitated comparisons between the different identifying genetic changes in coding and regulatory species and increased interactions among organism- genomic regions that are unique to humans, and are based research communities.