The History and Architecture of Petra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protecting and Presenting Petra to the World

Protecting and Presenting Petra to the World Petra Development &Tourism Region Authority Significance Petra is an outstanding example of cultural and natural landscape where human settlement and land use can be traced for over 10,000 years. Background . A 264 Km2 protected area containing archaeology and natural assets . World Heritage Site since 1985 . Jordan’s most visited site . Declared a New Seven Wonder in 2007 Petra Development and Tourism Regional Authority A new law established PDTRA in September 2009 Comprehensive & Sustainable Development Regulator for Economic activities Implement International Best Practices to Manage the Park Create an enabling environment for investment Vision New Master Plan for the region Develop Required Infrastructure to Boost Investments Promote Public -Private - Partnership Enhance the Competitiveness of Petra as a World- Class Tourism Destination Improve Services/ Diversify Tourism Products Local Community Development Protect and present the Park Work Plan The Challenge: 1. PDTRA Institutional Framework 2. Petra Archaeological Park Conservation & Management 3. The Petra Experience 4. Human Resources Development & Awareness 5. Local Community Development 6. Marketing & Communication Petra Archaeological Park Conservation & Presentation How this work plan was informed The Challenge: .Building on previous work and consultations with key stakeholders Ministry of Tourism & Antiquities Department of Antiquities District Governorate USAID . Participatory Rapid Appraisal UNESCO Shop owners -

Jeffrey Eli Pearson

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Contextualizing the Nabataeans: A Critical Reassessment of their History and Material Culture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4dx9g1rj Author Pearson, Jeffrey Eli Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Contextualizing the Nabataeans: A Critical Reassessment of their History and Material Culture By Jeffrey Eli Pearson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Erich Gruen, Chair Chris Hallett Andrew Stewart Benjamin Porter Spring 2011 Abstract Contextualizing the Nabataeans: A Critical Reassessment of their History and Material Culture by Jeffrey Eli Pearson Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology University of California, Berkeley Erich Gruen, Chair The Nabataeans, best known today for the spectacular remains of their capital at Petra in southern Jordan, continue to defy easy characterization. Since they lack a surviving narrative history of their own, in approaching the Nabataeans one necessarily relies heavily upon the commentaries of outside observers, such as the Greeks, Romans, and Jews, as well as upon comparisons of Nabataean material culture with Classical and Near Eastern models. These approaches have elucidated much about this -

Parthenon 1 Parthenon

Parthenon 1 Parthenon Parthenon Παρθενών (Greek) The Parthenon Location within Greece Athens central General information Type Greek Temple Architectural style Classical Location Athens, Greece Coordinates 37°58′12.9″N 23°43′20.89″E Current tenants Museum [1] [2] Construction started 447 BC [1] [2] Completed 432 BC Height 13.72 m (45.0 ft) Technical details Size 69.5 by 30.9 m (228 by 101 ft) Other dimensions Cella: 29.8 by 19.2 m (98 by 63 ft) Design and construction Owner Greek government Architect Iktinos, Kallikrates Other designers Phidias (sculptor) The Parthenon (Ancient Greek: Παρθενών) is a temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena, whom the people of Athens considered their patron. Its construction began in 447 BC and was completed in 438 BC, although decorations of the Parthenon continued until 432 BC. It is the most important surviving building of Classical Greece, generally considered to be the culmination of the development of the Doric order. Its decorative sculptures are considered some of the high points of Greek art. The Parthenon is regarded as an Parthenon 2 enduring symbol of Ancient Greece and of Athenian democracy and one of the world's greatest cultural monuments. The Greek Ministry of Culture is currently carrying out a program of selective restoration and reconstruction to ensure the stability of the partially ruined structure.[3] The Parthenon itself replaced an older temple of Athena, which historians call the Pre-Parthenon or Older Parthenon, that was destroyed in the Persian invasion of 480 BC. Like most Greek temples, the Parthenon was used as a treasury. -

The Garter Room at Stowe House’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Michael Bevington, ‘The Garter Room at Stowe House’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XV, 2006, pp. 140–158 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2006 THE GARTER ROOM AT STOWE HOUSE MICHAEL BEVINGTON he Garter Room at Stowe House was described as the Ball Room and subsequently as the large Tby Michael Gibbon as ‘following, or rather Library, which led to a three-room apartment, which blazing, the Neo-classical trail’. This article will show Lady Newdigate noted as all ‘newly built’ in July that its shell was built by Lord Cobham, perhaps to . On the western side the answering gallery was the design of Capability Brown, before , and that known as the State Gallery and subsequently as the the plan itself was unique. It was completed for Earl State Dining Room. Next west was the State Temple, mainly in , to a design by John Hobcraft, Dressing Room, and the State Bedchamber was at perhaps advised by Giovanni-Battista Borra. Its the western end of the main enfilade. In Lady detailed decoration, however, was taken from newly Newdigate was told by ‘the person who shewd the documented Hellenistic buildings in the near east, house’ that this room was to be ‘a prodigious large especially the Temple of the Sun at Palmyra. Borra’s bedchamber … in which the bed is to be raised drawings of this building were published in the first upon steps’, intended ‘for any of the Royal Family, if of Robert Wood’s two famous books, The Ruins of ever they should do my Lord the honour of a visit.’ Palmyra otherwise Tedmor in the Desart , in . -

Tine Statue of Athena in the Parthenon

REMARKS UPON THE COLOSSALCHRYSELEPHAN- TINE STATUE OF ATHENA IN THE PARTHENON INTRODUCTION IT is not to be expectedthat even fragmentsof the gold and ivory colossal statue of Athena in the Parthenon should have survived the ravages of time. However, a good deal is known about the statue from small copies in the round and from coins, plaques, gems and the like; also, the famous statue is mentioned by ancient writers, sometimes at considerable length. Consequently we have a fairly good idea of her appearance. And when we come to consider the pedestal on which the statue stood, we find that there are data which can be studied to advantage. Obviously the importance of the statue called for a carefully designed pedestal. Thus it is desirable that all existing data concerning the pedestal be recorded. Let us, then, make a few remarks not only about the colossal statue, but also about the pedestal on which the statue stood. I ATHENA PARTHENOS, THE CLIMAX OF THE PANATHENEA Figure 1 shows the position of the colossal statue (often referred to as the Parthenos) in the east cella of the temple. The blocks which give the position of the statue are toward the west end of the nave and on the axis of the temple. They are poros blocks of the type used for foundations. They are flush with the marble pave- ment of the nave, and they are in situ. The poros blocks, thirty in number, cover an area so extensive that they at once tell us that the statue which stood above them was of colossal size (Figs. -

Nabataean Jewellery and Accessories

1 Nabataean Jewellery and Accessories Eyad Almasri [email protected] Firas Alawneh [email protected] Fadi Bala'awi [email protected] Queen Rania's Institute of Tourism and Heritage Hashemite University Zarqa- Jordan ABSTRACT In ancient times, jewellery and accessories were considered as one of the most important features of civilized societies. In addition to its aesthetic purpose, it used to reflect the high status of deities and humans; an amulet as part of a personal ornament was considered to give its wearer magical means, powers and protection. Due to the lack of written information about Nabataean jewellery and accessories, the purpose of this research is to fill the gap in information about jewellery and its role in Nabataean society. The research uses archaeological findings to reach a better understanding of the kinds, shapes and material of Nabataean jewellery and accessories and its function and symbolism in Nabataean society. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Before we present information about Nabataean Jewellery and accessories, it worth to present a short narrative identifying the history and the location of the Nabataean kingdom being studied. 2 From as early as the second century BC until the beginning of the second century AD a large part of Wadi Araba and Negev of what is now southern Jordan and Israel, together with the northwest corner of Saudi Arabia in addition to Hauran region and Jebel El-Drouz on the southern part of Syria and Sinai in Egypt, was ruled from the city of Petra the capital of the Nabataean kingdom by a succession of kings who called themselves kings of the Nabatu (Fig. -

DOCTORAL THESIS Interpretation and Presentation of Nabataeans Innovative Technologies: Case Study Petra/Jordan

DOCTORAL THESIS Interpretation and Presentation of Nabataeans Innovative Technologies: Case Study Petra/Jordan Submitted to the Faculty of Architecture, Civil Engineering, and Urban Planning Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus, Germany, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Engineer (Dr. Ing), 2006-2011 by Yazan Safwan Al-Tell (Born 07-04-1977 in Amman, Jordan) Supervisors: Prof. Dr. h.c. Jörg J. Kühn Prof.Dr. Stephen G. Schmid Prof. Dr. Ing. Adolf Hoffmann I Abstract The Nabataeans were people of innovation and technology. Many clear evidences were left behind them that prove this fact. Unfortunately for a site like Petra, visited by crowds of visitors and tourists every day, many major elements need to be strengthened in terms of interpretation and presentation techniques in order to reflect the unique and genuine aspects of the place. The major elements that need to be changed include: un-authorized tour guides, insufficient interpretation site information in terms of quality and display. In spite of Jordan‘s numerous archaeological sites (especially Petra) within the international standards, legislations and conventions that discuss intensively interpretation and presentation guidelines for archaeological site in a country like Jordan, it is not easy to implement these standards in Petra at present for several reasons which include: presence of different stakeholders, lack of funding, local community. Moreover, many interpretation and development plans were previously made for Petra, which makes it harder to determine the starting point. Within the work I did, I proposed two ideas for developing interpretation technique in Petra. First was using the theme technique, which creates a story from the site or from innovations done by the inhabitants, and to be presented to visitors in a modern approach. -

February 7, 2021 Jordan $4,965

Bethlehem Sea of Galilee Nazareth HOLY LAND HERITAGE & Jordan Jerusalem January 25 – February 7, 2021 Jordan $4,965. *DOUBLE OCCUPANCY Single Supplement Add $680 Inclusions: R/T Air - Fargo/Bismarck - Subject to change Hotel List: Leonardo Plaza– Netanya • 4 Star Accommodations Maagan - Tiberias • Baggage Handling at Hotel Ambassador – Jerusalem • 21 Included Meals Petra Guest House – Petra • Caesarea Maritima * Plain of Jezreel Dead Sea Spa Hotel – Dead • Nazareth * Sea of Galilee Sea • Beth Saida * Capernaum * Chorazin • Jordan River * Jordan Valley • Caesarea Philippi * Golan Heights • Beth Shean * Ein Harod * Jericho • Mt. of Olives * Rachael’s Tomb For Reservations Contact: • Bethlehem * Dead Sea Scrolls JUDY’S LEISURE TOURS • Jerusalem * Bethany * Masada *Passport is required • Dung Gate * Western Wall Valid for 6 months 4906 16 STREET N • Pools of Bethesda * St. Anne’s Church beyond travel date. Fargo, ND 58102 • King David’s Tomb • Mt. Zion * Garden Tomb 701/232-3441 or • Jordan * Petra * Seir Mountains • Royal Tombs * Historical King’s Highway 800/598-0851 • Madaba * Mt Nebo • Baptismal Site “Bethany beyond the Jordan” Insurance $382. Purchase at time of Deposit Day 1 & 2: We will depart the United States for overnight travel to Israel. After clearing customs, we will be met by our guide who will take us on a scenic drive through Jaffa, the oldest port in the world. Jonah set sail for Tarshish from Jaffa but was swallowed by a large fish. Jaffa was also the home of Tabitha, who was raised from the dead by Peter. Peter had his vision here while lodging in the home of Simon the Tanner. -

Ancient Greek Architecture

Greek Art in Sicily Greek ancient temples in Sicily Temple plans Doric order 1. Tympanum, 2. Acroterium, 3. Sima 4. Cornice 5. Mutules 7. Freize 8. Triglyph 9. Metope 10. Regula 11. Gutta 12. Taenia 13. Architrave 14. Capital 15. Abacus 16. Echinus 17. Column 18. Fluting 19. Stylobate Ionic order Ionic order: 1 - entablature, 2 - column, 3 - cornice, 4 - frieze, 5 - architrave or epistyle, 6 - capital (composed of abacus and volutes), 7 - shaft, 8 - base, 9 - stylobate, 10 - krepis. Corinthian order Valley of the Temples • The Valle dei Templi is an archaeological site in Agrigento (ancient Greek Akragas), Sicily, southern Italy. It is one of the most outstanding examples of Greater Greece art and architecture, and is one of the main attractions of Sicily as well as a national momument of Italy. The area was included in the UNESCO Heritage Site list in 1997. Much of the excavation and restoration of the temples was due to the efforts of archaeologist Domenico Antonio Lo Faso Pietrasanta (1783– 1863), who was the Duke of Serradifalco from 1809 through 1812. • The Valley includes remains of seven temples, all in Doric style. The temples are: • Temple of Juno, built in the 5th century BC and burnt in 406 BC by the Carthaginians. It was usually used for the celebration of weddings. • Temple of Concordia, whose name comes from a Latin inscription found nearby, and which was also built in the 5th century BC. Turned into a church in the 6th century AD, it is now one of the best preserved in the Valley. -

Temples with Transverse Cellae in Republican and Early Imperial Italy

BABesch 82 (2007, 333-346. doi: 10.2143/BAB.82.2.2020781) Forms of Cult? Temples with transverse cellae in Republican and early Imperial Italy Benjamin D. Rous Abstract This article presents an analysis of a particular temple type that first appeared during the Late Republic, the temple with transverse cella. In the past this particular cella-form has been interpreted as a solution to spatial constraints. In more recent times it has been argued that the cult associated with the temple was the decisive factor in the adoption of the transverse cella. Neither theory, when considered in isolation, can fully and con- vincingly explain the particular forms of both Republican and Imperial temples. Rather, it can be argued that a combination of pragmatic and above all aesthetic considerations has played a major role in the particular archi- tecture of these temples.* INTRODUCTION archaeological evidence, even though the remains of the building itself have never been excavated. In the fourth book of his famous treatise on archi- Furthermore, this is one of the temples actually tecture, Vitruvius mentions a specific temple-type, mentioned by Vitruvius in his treatise. In yet an- whose basic characteristic is that all the features other case, the temple of Aesculapius in the Latin normally found on the short side of the temple colony of Fregellae, although construction activi- have been transferred to the long side. What this ties have destroyed virtually the entire temple basically means is that the pronaos still constitutes building, a reconstruction of a transverse cella the front part of the temple, but instead of being nevertheless seems likely on the basis of the scant longitudinally developed, the cella is rotated 90º remains we do have. -

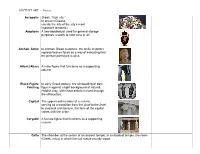

Art Concepts

ANCIENT ART - Greece Acropolis Greek, “high city.” In ancient Greece, usually the site of the city’s most important temple(s). Amphora A two-handled jar used for general storage purposes, usually to hold wine or oil. Archaic Smile In Archaic Greek sculpture, the smile sculptors represented on faces as a way of indicating that the person portrayed is alive. Atlant (Atlas) A male figure that functions as a supporting column. Black-Figure In early Greek pottery, the silhouetting of dark Painting figures against a light background of natural, reddish clay, with linear details incised through the silhouettes. Capital The uppermost member of a column, serving as a transition from the shaft to the lintel. In classical architecture, the form of the capital varies with the order. Caryatid A female figure that functions as a supporting column. Cella The chamber at the center of an ancient temple; in a classical temple, the room (Greek, naos) in which the cult statue usually stood. ANCIENT ART - Greece Centaur In ancient Greek mythology, a fantastical creature, with the front or top half of a human and the back or bottom half of a horse. Contrapposto The disposition of the human figure in which one part is turned in opposition to another part (usually hips and legs one way, shoulders and chest another), creating a counterpositioning of the body about its central axis. Sometimes called “weight shift” because the weight of the body tends to be thrown to one foot, creating tension on one side and relaxation on the other. Corinthian Corinthian columns are the latest of the three Greek styles and show the influence of Egyptian columns in their capitals, which are shaped like inverted bells. -

A Roman Temple in the Ancient City of Petra Yr. 6

A Roman Temple in The Ancient City of Petra Yr. 6 Theme: Who or what is God? Context: exploration of a ritual in an ancient temple in the ruined city of Petra, Jordan. Overview of learning: - To investigate Ancient Roman beliefs and rituals relating to their gods. - To explore the specific ritual of sacrifice to the Roman gods. - To understand that the Jewish people of the time worshipped one god and had a different set of beliefs to the Romans. Interesting aspects: - That some religions worship one god and others many gods. - That the ritual of live sacrifice is used in some religions to honour / placate their deities. - That people from different religions can live alongside each other, but in unequal circumstances. - That a group of people might have to hide / suppress their beliefs through fear of persecution or punishment. Inquiry questions: - Why do some religions worship multiple gods and some one god? - Why do religions have special rituals, ceremonies, clothes and places of worship? - What was involved in an Ancient Roman ritual of a live sacrifice ? - How can the beliefs of one group of people upset or offend the beliefs of another? Narrative: The year is AD 150. The date is October 15th, the date of the annual Great Chariot Race in Petra. A noble Roman family are celebrating the victory of their chariot. They know that one of the winning horses in their chariot team must now be sacrificed to Mars, the god of war, one of the most powerful gods. They are proud that their horse is to be sacrificed as it will bring them good fortune.