''Potential Lesbians at Two O'clock'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10.9 De Jesus Precarious Girlhood Dissertation Draft

! ! "#$%&#'()*!+'#,-((./!"#(0,$1&2'3'45!6$%(47'5)#$.!8#(9$*!(7!:$1'4'4$!;$<$,(91$42! '4!"(*2=>??@!6$%$**'(4&#A!B'4$1&! ! ! ;$*'#C$!.$!D$*)*! ! ! ! ! E!8-$*'*! F4!2-$!! G$,!H(99$4-$'1!I%-((,!(7!B'4$1&! ! ! ! ! "#$*$42$.!'4!"'&,!:),7',,1$42!(7!2-$!6$J)'#$1$42*! :(#!2-$!;$5#$$!(7! ;(%2(#!(7!"-',(*(9-A!K:',1!&4.!G(<'45!F1&5$!I2).'$*L! &2!B(4%(#.'&!M4'<$#*'2A! G(42#$&,N!O)$0$%N!B&4&.&! ! ! ! ! ! P%2(0$#!>?Q@! ! R!;$*'#C$!.$!D$*)*N!>?Q@ ! ! CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Desirée de Jesus Entitled: Precarious Girlhood: Problematizing Reconfigured Tropes of Feminine Development in Post-2009 Recessionary Cinema and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Film and Moving Image Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Dr. Lorrie Blair External Examiner Dr. Carrie Rentschler External to Program Dr. Gada Mahrouse Examiner Dr. Rosanna Maule Examiner Dr. Catherine Russell Thesis Supervisor Dr. Masha Salazkina Approved by Dr. Masha Salazkina Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director December 4, 2019 Dr. Rebecca Duclos Dean Faculty of Fine Arts ! ! "#$%&"'%! ()*+,)-./0!1-)23..45!().62*7,8-9-:;!&*+.:<-;/)*4!%).=*0!.<!>*7-:-:*!?*@*2.=7*:8!-:! (.08ABCCD!&*+*00-.:,)E!'-:*7,! ! ?*0-)F*!4*!G*0/0! '.:+.)4-,!H:-@*)0-8EI!BCJD! ! !"##"$%&'()*+(,--.(/#"01#(2+3+44%"&5()*+6+($14(1(4%'&%7%31&)(3*1&'+(%&()*+(3%&+81)%3(9+:%3)%"&( -

17 December 2003

Screen Talent Agency 818 206 0144 JUDY GELLMAN Costume Designer judithgellman.wordpress.com Costume Designers Guild, locals 892 & 873 Judy Gellman is a rarity among designers. With a Midwest background and training at the University of Wisconsin and The Fashion Institute of Technology (NYC) Judy began her career designing for the Fashion Industry before joining the Entertainment business. She’s a hands-on Designer, totally knowledgeable in pattern making, construction, color theory, as well as history and drawing. Her career has taken her from Chicago to Toronto, London, Vancouver and Los Angeles designing period, contemporary and futuristic styles for Men, Women, and even Dogs! Gellman works in collaboration with directors to instill a sense of trust between her and the actors as they create the characters together. This is just one of the many reasons they turn to Judy repeatedly. Based in Los Angeles, with USA and Canadian passports she is available to work worldwide. selected credits as costume designer production cast director/producer/company/network television AMERICAN WOMAN Alicia Silverstone, Mena Suvari (pilot, season 1) various / John Riggi, John Wells, Jinny Howe / Paramount TV PROBLEM CHILD Matthew Lillard, Erinn Hayes (pilot) Andrew Fleming / Rachel Kaplan, Liz Newman / NBC BAD JUDGE Kate Walsh, Ryan Hansen (season 1) various / Will Farrell, Adam McKay, Joanne Toll / NBC SUPER FUN NIGHT Rebel Wilson (season 1) various / Conan O’Brien, John Riggi, Steve Burgess / ABC SONS OF TUCSON Tyler Labine (pilot & series) Todd Holland, -

Not Another Teen Movie”

Uncovering the Function of Taboo Words Used in “Not Another Teen Movie” Dian Mukti Primasari1, Alek2 , Didin Nuruddin Hidayat3, and Dhuha Hadiyansyah4 {[email protected] 1, [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]} 1,2,3,4UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta, Indonesia Abstract. The study investigated the use of taboo words in a specific movie, namely Not Another Teen Movies. Taboo stimuli are exceptionally stirring, yet it has been recommended that they likewise have inborn explicit properties, for example, taboo, offensiveness, disagreeableness, or even shock value. Nonetheless, taboo words frequently contrast from different words on something beyond excitement and forbidden properties. In the present study, the researchers replicated both of these discoveries and directed detailed item analyses to figure out which word properties drive a few impacts. The study concludes that the taboo words have several functions. Those are expressing desire, insulting people, expressing pride, cursing and disappointment, metaphor, literal meaning, openness, and hatred expression. Keywords: taboo, words analysis, word function 1. INTRODUCTION Swear words and taboo words can heighten what are stated, yet they can stun or give offense. Swearing and the utilization of forbidden words and articulations are very basic in talking. We frequently hear and use them both in private and in open settings and in movies, on TV and on the radio. The utilization of forbidden articulations recommends that speakers have, or wish to have, a nearby close to home association with others [1]. We additionally utilize unthinkable articulations and swear words when we express solid sentiments, or when we wish to undermine or to be upsetting to other people [2]. -

Affleck Steps out for Haircut Between Rehab

16 TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 11, 2018 THE NUN SEEF (I) 11.30 AM + 2.30 + 5.30 + 8.30 + 11.30 TOM CRUISE, HENRY CAVILL, VING RHAMES (18+) (HORROR/THRILLER) NEW WADI AL SAIL 3.15+ 8.15 PM CINECO (20) 11.30 AM + 2.30 + 5.30 + 8.30 + TAISSA FARMIGA, DEMIAN BICHIR, 11.30 PM BONNIE AARONS THE MEG SEEF (II) 12.00 + 6.00 PM + 12.00 MN CINECO (20) (IMAX 2D): 12.15 + 2.30 + 4.45 (PG-15) (ACTION/THRILLER) + 7.00 + 9.15 + 11.30 PM (1.00 AM THURS/FRI) JASON STATHAM, RUBY ROSE, BINGBING LI SKYSCRAPER Affleck steps (ATMOS): 10.30 AM + 12.45 + 3.00 + 5.15 + 7.30 CINECO (20) 11.30 AM + 2.00 + 4.30 + 7.00 + (PG-13) (ACTION/THRILLERA/DRAMA) + 9.45 PM + 12.00 MN (VIP I): 11.45 AM + 2.00 + 9.30 PM + 12.00 MN DWAYNE JOHNSON, NEVE CAMPBELL, PABLO 4.15 + 6.30 + 8.45 + 11.00 PM SCHREIBER SEEF (II) 11.00 AM + 1.30 + 4.00 + 6.30 + 9.00 SEEF (II) (1.00 AM THURS/FRI) + 11.30 PM CINECO (20) 12.00 + 2.15 + 4.30 + 6.45 + 9.00 + 11.15 PM SEEF (I) 12.30 + 2.45 + 5.00 + 7.15 + 9.30 + WADI AL SAIL 10.45 AM + 1.15 + 3.45 + 6.15 + 11.45 PM out for haircut 8.45 + 11.15 PM SAAR 12.00 + 2.15 + 4.30 + 6.45 + 9.00 + (11.15 CHRISTOPHER ROBIN PM THURS/FRI) EL BADLAH (PG) (FAMILY/ADVENTURE/COMEDY) EWAN MCGREFOR, HAYLEY ATWELL, BRONTE WADI AL SAIL 10.30 AM + 12.45 + 3.00 + 5.15 + (PG-13) (ARABIC/COMEDY) CARMICHAEL 7.30 + 9.15 PM + 11.30 PM TAMER HOSNY, AKRAM HOSNI, MAJED EL MASRY, AMINA KHALIL CINECO (20) 11.30 AM + 4.15 + 9.00 PM SEEF (II) 11.45 AM + 2.00 + 4.15 + 6.30 PM between rehab ALPHA CINECO (20) 12.00 + 2.00 + 4.00 + 6.00 + 8.00 (PG-13) (ADVENTURE) NEW + 10.00 PM + 12.00 MN IANS | Malibu KODI SMIT-MCPHEE, JOHANNES SEEF (II) (12.45 MN THURS/FRI) THE INCREDIBLES 2 HAUKUR JOHANNESSON (PG) (ANIMATION/ACTION/ADVENTURE) SEEF (I) 11.15 AM + 1.15 + 3.15 + 5.15 + 7.15 + CRAIG T. -

Soap Opera Digest 2021 Publishing Calendar

2021 MEDIA KIT Soap Opera Digest 2021 Publishing Calendar Issue # Issue Date On Sale Date Close Date Materials Due Date 1 01/04/21 12/25/20 11/27/20 12/04/20 2 01/11/21 01/01/21 12/04/20 12/11/20 3 01/18/21 01/08/21 12/11/20 12/18/20 4 01/25/21 01/15/21 12/18/20 12/25/20 5 02/01/21 01/22/21 12/25/20 01/01/21 6 02/08/21 01/29/21 01/01/21 01/08/21 7 02/15/21 02/05/21 01/08/21 01/15/21 8 02/22/21 02/12/21 01/15/21 01/22/21 9 03/01/21 02/19/21 01/22/21 01/29/21 10 03/08/21 02/26/21 01/29/21 02/05/21 11 03/15/21 03/05/21 02/05/21 02/12/21 12 03/22/21 03/12/21 02/12/21 02/19/21 13 03/29/21 03/19/21 02/19/21 02/26/21 14 04/05/21 03/26/21 02/26/21 03/05/21 15 04/12/21 04/02/21 03/05/21 03/12/21 16 04/19/21 04/09/21 03/12/21 03/19/21 17 04/26/21 04/16/21 03/19/21 03/26/21 18 05/03/21 04/23/21 03/26/21 04/02/21 19 05/10/21 04/30/21 04/02/21 04/09/21 20 05/17/21 05/07/21 04/09/21 04/16/21 21 05/24/21 05/14/21 04/16/21 04/23/21 22 05/31/21 05/21/21 04/23/21 04/30/21 23 06/07/21 05/28/21 04/30/21 05/07/21 24 06/14/21 06/04/21 05/07/21 05/14/21 25 06/21/21 06/11/21 05/14/21 05/21/21 26 06/28/21 06/18/21 05/21/21 05/28/21 27 07/05/21 06/25/21 05/28/21 06/04/21 28 07/12/21 07/02/21 06/04/21 06/11/21 29 07/19/21 07/09/21 06/11/21 06/18/21 30 07/26/21 07/16/21 06/18/21 06/25/21 31 08/02/21 07/23/21 06/25/21 07/02/21 32 08/09/21 07/30/21 07/02/21 07/09/21 33 08/16/21 08/06/21 07/09/21 07/16/21 34 08/23/21 08/13/21 07/16/21 07/23/21 35 08/30/21 08/20/21 07/23/21 07/30/21 36 09/06/21 08/27/21 07/30/21 08/06/21 37 09/13/21 09/03/21 08/06/21 08/13/21 38 09/20/21 -

For Immediate Release

‘ICE DREAMS’ CAST BIOS SHELLEY LONG (Harriet Clayton) – Shelley Long is an Emmy® and Golden Globe-winning actress. She began her career after attending Northwestern University by performing in small films and local theater, eventually becoming co-host and associate producer of a critically acclaimed Chicago magazine show “Sorting it Out,” for which she won three local Emmys. She eventually returned to her first passion, acting, and joined Chicago’s famed Second City improvisational comedy troupe. Shortly after, Long landed a role as barmaid Diane Chambers in the long-running NBC comedy “Cheers.” Long entertained audiences for five seasons, garnering an Emmy and two Golden Globes. She returned for the series’ top-rated finale and has reprised her “Cheers” role in guest appearances on NBC’s “Frasier,” one episode garnering an Emmy nomination. Long recently starred in a film short titled “A Couple of White Chicks at the Hairdresser,” and starred in a children’s DVD, “Mr. Vinegar and the Curse.” In 2006, Long starred in “Honeymoon With Mom” on Lifetime, and co-starred in the Hallmark Channel Valentine’s Day movie, “Falling In Love with the Girl Next Door.” She has made a number of guest TV appearances including “Boston Legal,” “Yes, Dear, “Joan of Arcadia,” “Complete Savages” and, most recently, ABC’s hit comedy “Modern Family.” Long was seen in the Robert Altman film “Dr. T and the Women” for Artisan Entertainment. Written by Anne Rapp and executive produced by Cindy Cowan and James McLindon, the film tells the story of a gynecologist, played by Richard Gere, who is battling a mid-life crisis. -

Movielistings

6b The Goodland Star-News / Friday, August 10, 2007 Like puzzles? Then you’ll love sudoku. This mind-bending puzzle will have FUN BY THE NUMBERS you hooked from the moment you square off, so sharpen your pencil and put your sudoku savvy to the test! Here’s How It Works: Sudoku puzzles are formatted as a 9x9 grid, broken down into nine 3x3 boxes. To solve a sudoku, the numbers 1 through 9 must fill each row, col- umn and box. Each number can appear only once in each row, column and box. You can figure out the order in which the numbers will appear by using the numeric clues already provided in the boxes. The more numbers you name, the easier it gets to solve the puzzle! ANSWER TO TUESDAY’S SATURDAY EVENING AUGUST 11, 2007 SUNDAY EVENING AUGUST 12, 2007 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone Family Family Family Family: Coreys: Wing Two Coreys Confessn Confessions Family Family Flip This House (TV G) Flip This House: The American Justice (TVPG) American Justice: Who Flip This House (TV G) 36 47 A&E 36 47 A&E (R) Montelongo Bunch (N) (R) Whacked Zack? (R) (R) Jewels (R) Jewels (R) Jewels (R) Genetopia Man (R) (TV14) (R) Jewels (R) Jewels (R) aa Extreme Makeover: Desperate Housewives: Brothers & Sisters: All in the KAKE News (:35) KAKE (:05) Lawyer (:35) Paid “Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle” (‘03) Masters of Science Fiction KAKE News (:35) American Idol Re- (:35) Enter- 4 6 ABC 4 6 ABC Cameron Diaz. -

Press-Release-The-Endings.Pdf

Publication Date: September 4, 2018 Media Contact: Diane Levinson, Publicity [email protected] 212.354.8840 x248 The Endings Photographic Stories of Love, Loss, Heartbreak, and Beginning Again By Caitlin Cronenberg and Jessica Ennis • Foreword by Mary Harron 11 x 8 in, 136pp, Hardcover, Photographs throughout ISBN 978‐1‐4521‐5568‐5, $29.95 Featuring some of today’s most celebrated actresses, including Julianne Moore, Alison Pill, and Imogen Poots, the photographic vignettes in The Endings capture female characters in the throes of emotional transformation. Photographer Caitlin Cronenberg and art director Jessica Ennis created stories of heartbreak, relationship endings, and new beginnings—fictional but often inspired by real life—and set out to convey the raw emotions that are exposed in these most vulnerable states. Cronenberg and Ennis collaborated with each actress to develop a character, build the world she inhabits, and then photograph her as she lived the role before the camera. Patricia Clarkson depicts a woman meeting her younger lover in the campus library—even though they both know the relationship has been over since before it even began. Juno Temple portrays a broken‐hearted woman who engages in reckless and self‐destructive behavior to numb the sadness she feels. Keira Knightley ritualistically cleanses herself and her home after the death of her great love. Also featured are Jennifer Jason Leigh, Danielle Brooks, Tessa Thompson, Noomi Rapace, and many more. These intimate images combine the lush beauty and rich details of fashion photographs with the drama and narrative energy of film stills. Telling stories of sadness, loneliness, anger, relief, rebirth, freedom, and happiness, they are about relationship endings, but they are also about beginnings. -

ARSENIC and OLD LACE Written by Joseph Kesselring Directed by Elina De Santos

ARSENIC AND OLD LACE Written by Joseph Kesselring Directed by Elina de Santos STARRING Alan Abelew, Michael Antosy, Ron Bottitta, Jacque Lynn Colton, Sheelagh Cullen, Darius De La Cruz, Alex Elliott-Funk, Mat Hayes, Gera Hermann, Liesel Kopp, Yusef Lambert, JB Waterman SCENIC DESIGNER COSTUME DESIGNER LIGHTING DESIGNER SOUND DESIGNER Bruce Goodrich Amanda Martin Leigh Allen Christopher Moscatiello PROP DESIGNER FIGHT CHOREOGRAPHER STAGE MANAGER ASSISTANT DIRECTORS Josh La Cour Jenine MacDonald Morgan Wilday Ellen Boener Everett Keeter Produced by the Odyssey Theatre Ensemble "Presented by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Service, Inc., New York.” Arsenic and Old Lace performance schedule: August 26th through October 8th, 2017 The Odyssey is supported in part by a grant from the City of Los Angeles, Department of Cultural Affairs, and Los Angeles County Arts Commission. The video and/or audio recording of this performance by any means whatsoever is strictly prohibited. ODYSSEY THEATRE ENSEMBLE: 2055 South Sepulveda Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90025 Administration and Box Office: 310-477-2055 ext 2 FAX: 310-444-0455 [email protected] www.odysseytheatre.com CAST (In order of appearance.) ABBY BREWSTER ........................................................Sheelagh Cullen REV.DR.HARPER/ MR. WITHERSPOON/ MR. GIBBS .............Alan Abelew TEDDY BREWSTER ........................................................Alex Elliott-Funk OFFICER BROPHY .............................................................. Mat Hayes OFFICER KLEIN -

Days of Health & Fitness

THE BYRON SHIRE Volume 24 #45 SCENE Tuesday, April 20, 2010 N Mullumbimby 02 6684 1777 E Byron Bay 02 6685 5222 E Fax 02 6684 1719 R [email protected] [email protected] G www.echo.net.au page 18 21,000 copies every week CROUCHING HACK, HIDDEN SNAPPER Rate increase Tallowood still on protesters’ radar in shire plan The 2010-2013 Draft Management Plan and Budget is on public exhibi- tion until 10 May 2010. Byron Shire Mayor Jan Barham said the draft plan details the services and programs to be delivered by Council along with an overview of capital works planned for 2010/11. ‘It’s a challenging budget for this upcoming financial year,’ she said in a press release. ‘The recently an- nounced rate pegging of 2.6 per cent by the NSW government makes it impossible to maintain the level of service expected by our residents and ratepayers. ‘A 2.6 per cent cap does not cover the real costs that Council experi- ences and doesn’t allow for increases in electricity, wages and equipment. Unfortunately, the continual cost shifting from the state government to local councils will mean a special rate application for Council for the upcoming financial year.’ Council is seeking a 6.98% special rate increase for 2010/11. The rate in- crease on the general fund will be used for one million dollars’ worth of services and programs including the new Byron Bay Library $100,000, Byron Sport and Cultural Complex $120,000, Byron Regional Sport and Cultural Complex maintenance $186,000, increased regional library Protesters gathered last Saturday at the proposed Tallowood Ridge Estate subdivision site at Mullumbimby to reinforce their call for residents to attend a contribution $84,000, information Land and Environment Court hearing at the Byron Bay courthouse on Wednesday April 28. -

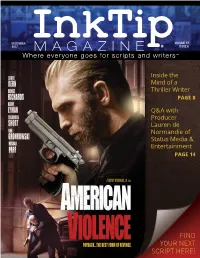

MAGAZINE ® ISSUE 6 Where Everyone Goes for Scripts and Writers™

DECEMBER VOLUME 17 2017 MAGAZINE ® ISSUE 6 Where everyone goes for scripts and writers™ Inside the Mind of a Thriller Writer PAGE 8 Q&A with Producer Lauren de Normandie of Status Media & Entertainment PAGE 14 FIND YOUR NEXT SCRIPT HERE! CONTENTS Contest/Festival Winners 4 Feature Scripts – FIND YOUR Grouped by Genre SCRIPTS FAST 5 ON INKTIP! Inside the Mind of a Thriller Writer 8 INKTIP OFFERS: Q&A with Producer Lauren • Listings of Scripts and Writers Updated Daily de Normandie of Status Media • Mandates Catered to Your Needs & Entertainment • Newsletters of the Latest Scripts and Writers 14 • Personalized Customer Service • Comprehensive Film Commissions Directory Scripts Represented by Agents/Managers 40 Teleplays 43 You will find what you need on InkTip Sign up at InkTip.com! Or call 818-951-8811. Note: For your protection, writers are required to sign a comprehensive release form before they place their scripts on our site. 3 WHAT PEOPLE SAY ABOUT INKTIP WRITERS “[InkTip] was the resource that connected “Without InkTip, I wouldn’t be a produced a director/producer with my screenplay screenwriter. I’d like to think I’d have – and quite quickly. I HAVE BEEN gotten there eventually, but INKTIP ABSOLUTELY DELIGHTED CERTAINLY MADE IT HAPPEN WITH THE SUPPORT AND FASTER … InkTip puts screenwriters into OPPORTUNITIES I’ve gotten through contact with working producers.” being associated with InkTip.” – ANN KIMBROUGH, GOOD KID/BAD KID – DENNIS BUSH, LOVE OR WHATEVER “InkTip gave me the access that I needed “There is nobody out there doing more to directors that I BELIEVE ARE for writers than InkTip – nobody. -

![“Impact Winter” Guest: Ben Murray [Intro Music] JOSH: Hello, You're Listening to the West Wing](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2813/impact-winter-guest-ben-murray-intro-music-josh-hello-youre-listening-to-the-west-wing-912813.webp)

“Impact Winter” Guest: Ben Murray [Intro Music] JOSH: Hello, You're Listening to the West Wing

The West Wing Weekly 6.09: “Impact Winter” Guest: Ben Murray [Intro Music] JOSH: Hello, you’re listening to The West Wing Weekly. I’m Joshua Malina. HRISHI: And I’m Hrishikesh Hirway. Today, we’re talking about Season 6 Episode 9. It’s called “Impact Winter”. JOSH: This episode was written by Debora Cahn. This episode was directed by Lesli Linka Glatter. This episode first aired on December 15th, 2004. HRISHI: Two episodes ago, in episode 6:07, the title was “A Change is Gonna Come,” and I think in this episode the changes arrive. JOSH: Aaaahhh. HRISHI: The President goes to China, but he is severely impaired by his MS. Charlie pushes C.J. to consider her next step after she steps out of the White House, and Josh considers his next step after it turns out Donna has already considered what her next step will be. JOSH: Indeed. HRISHI: Later in this episode we’re going to be joined by Ben Murray who made his debut on The West Wing in the last episode. He plays Curtis, the president’s new personal assistant to replace Charlie. JOSH: A man who has held Martin Sheen in his arms. I mean, I’ve done that off camera, but he did it on television. HRISHI: [Laughs] Little do our listeners know that Martin Sheen insists on being carried everywhere. JOSH: That’s right. I was amazed all these years later when Martin showed up for his interview with us that Ben was carrying him. That was the first time we met him.