The Highways and Byways of the East Riding Enclosuresenclosures Andand Droversdrovers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humber Accord

HUMBER ACCORD (Caves, Cottingham (AWAKE (Anlaby, Willerby & Kirk Ella), Howden, Hornsea, Swanland, Hessle, Wolds, Pocklington, Beverley and Hull) Open door arrangements for U3A members Several years ago the U3As of Beverley, Caves, Cottingham, Hessle and Swanland formed the Accord network in order to share information, experience and ideas for their mutual benefit. Subsequently AWAKE (Anlaby, Willerby & Kirk Ella), Howden and District, Hornsea and District, Wolds, and Hull have been welcomed into the group. Meetings are held at approximately 3 monthly intervals and are attended by 2 Committee members (usually the Chairperson or Secretary and one other) from each U3A. There are some rules/guidelines to ensure the system operates fairly and is not abused. Individual U3As may vary the detail but are asked to honour the principles. PROTOCAL FOR RECIPROCAL ARRANGEMENTS: 1. To avoid confusion and/or problems, it would be helpful to develop common practise so all know how the system should work. 2. The system can apply to our Interests Groups, monthly/general/regular meetings and other events. 3. For all interest groups – the leader has total discretion about whether their group can accommodate an increase in membership or has space for guest visitors on an occasional basis. There will be no control of Groups by the local committees. 4. Members should always contact the leader of the group that they wish to attend – before attending. They should not just “drop in” on an ad hoc basis. 5. Leaders may wish to prioritise membership of their own U3A. This can be done by limiting external access until after a stated cut-off date or any other suitable system. -

Azalea House, Church Lane, Elloughton HU15

59d Welton Road, Brough, East Riding of Yorkshire HU15 1AB Tel: 01482 666816 | Email: [email protected] www.quickclarke.co.uk Azalea House, Church Lane, Elloughton HU15 1SP Offers in the region of £625,000 • Five double bedrooms 10' 7" x 9' 8" (3.23m x 2.95m) at the time of instruction and are intended to give a FINANCIAL SERVICES general description of the property at the time. Quick & Clarke are pleased to be able to offer • South Westerly facing garden UTILITY ROOM independent advice regarding mortgages and further • Superb tucked away position 16' 4" x 6' 8" (4.98m x 2.03m) GARAGE details can be obtained by contacting our Beverley • Close to primary school 16' 4" x 18' 11" (4.98m x 5.77m) office on 01482 886200. Independent advice will be WC given by a qualified financial services consultant and • EPC Rating: TBC 3' 7" x 8' 5" (1.09m x 2.57m) SERVICES written quotations are available upon request. This • Part Exchange Considered All mains services are available or connected to the could save you time and money when searching for the • Help to Buy Scheme Available FIRST FLOOR property. most competitive deals. Our mortgage adviser has access to every lending scheme currently available A fantastic and generous sized five bed family house on a MASTER BEDROOM CENTRAL HEATING through a computerised sourcing system. generous sized and tucked away plot offering a Southerly 17' 9" x 11' 8" (5.41m x 3.56m) The property benefits from a gas fired central heating facing garden very close to the centre of Elloughton. -

House Number Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Town/Area County

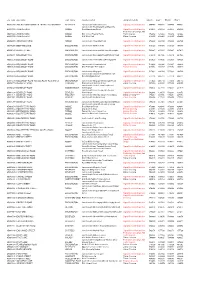

House Number Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Town/Area County Postcode 64 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 70 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 72 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 74 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 80 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 82 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 84 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 1 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 2 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 3 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 4 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 1 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 3 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 5 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 7 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 9 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 11 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 13 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 15 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 17 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 19 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 21 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 23 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 25 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 -

Pocklington School Bus Routes

OUR School and other private services MALTON RILLINGTON ROUTES Public services Revised Sept 2020 NORTON BURYTHORPE DRIFFIELD LEPPINGTON NORTH SKIRPENBECK WARTHILL DALTON GATE STAMFORD HELMSLEY BRIDGE WARTER FULL MIDDLETON NEWTON SUTTON ON THE WOLDS N ELVINGTON UPON DERWENT YORK KILNWICK SUTTON POCKLINGTON UPON DERWENT AUGHTON LUND COACHES LECONFIELD & MINIBUSES BUBWITH From York York B & Q MOLESCROFT WRESSLE MARKET Warthill WEIGHTON SANCTON Gate Helmsley BISHOP BEVERLEY Stamford Bridge BURTON HOLME ON NORTH Skirpenbeck SPALDING MOOR NEWBALD Full Sutton HEMINGBOROUGH WALKINGTON Pocklington SPALDINGTON SWANLAND From Hull NORTH CAVE North Ferriby Swanland Walkington HOWDEN SOUTH NORTH HULL Bishop Burton CAVE FERRIBY Pocklington From Rillington Malton RIVER HUMBER Norton Burythorpe HUMBER BRIDGE Pocklington EAST YORKSHIRE BUS COMPANY Enterprise Coach Services (am only) PUBLIC TRANSPORT South Cave Driffield North Cave Middleton-on-the-Wolds Hotham North Newbald 45/45A Sancton Hemingbrough Driffield Babthorpe Market Weighton North Dalton Pocklington Wressle Pocklington Breighton Please contact Tim Mills Bubwith T: 01430 410937 Aughton M: 07885 118477 Pocklington X46/X47 Hull Molescroft Beverley Leconfield Bishop Burton Baldry’s Coaches Kilnwick Market Weighton BP Garage, Howden Bus route information is Lund Shiptonthorpe Water Tower, provided for general guidance. Pocklington Pocklington Spaldington Road End, Routes are reviewed annually Holme on Spalding Moor and may change from year to Pocklington (am only) For information regarding year in line with demand. Elvington any of the above local Please contact Parents are advised to contact Sutton-on-Derwent service buses, please contact Mr Phill Baldry the Transport Manager, or the Newton-on-Derwent East Yorkshire Bus M:07815 284485 provider listed, for up-to-date Company Email: information, on routes, places Please contact the Transport 01482 222222 [email protected] and prices. -

BRI 51 1 Shorter-Contributions 307..387

318 SHORTER CONTRIBUTIONS An Early Roman Fort at Thirkleby, North Yorkshire By MARTIN MILLETT and RICHARD BRICKSTOCK ABSTRACT This paper reports the discovery through aerial photography of a Roman fort at Thirkleby, near Thirsk in North Yorkshire. It appears to have two structural phases, and surface finds indicate that it dates from the Flavian period. The significance of its location on the intersection of routes north–south along the edge of the Vale of York and east–west connecting Malton and Aldborough is discussed in the context of Roman annexation of the North. Keywords: Thirkleby; Roman fort; Roman roads; Yorkshire INTRODUCTION The unusually dry conditions in northern England in the summer of 2018 produced a substantial crop of new sites discovered through aerial photography. By chance, the Google Earth satellite image coverage for parts of Yorkshire has been updated with a set of images taken on 1 July 2018, during the drought. Amongst the numerous sites revealed in this imagery – often in areas where crop-marks are rarely visible – is a previously unknown Roman fort (FIG.1).1 The site (SE 4718 7728) lies just to the west of the modern A19, on the southern side of the Thirkleby beck at its confluence with the Carr Dike stream, about 6 km south-east of Thirsk. It is situated on level ground at a height of about 32 m above sea level on the southern edge of the flood plain of the beck, which is clearly visible on the aerial images. A further narrow relict stream bed runs beside it to the south-east. -

Site Code Site Name Town Name Design Location Designation Notes Start X Start Y End X End Y

site_code site_name town_name design_location designation_notes Start X Start Y End X End Y 45913280 ACC RD SWINEMOOR LA TO EAST RIDING HOSP BEVERLEY Junction with Swinemoor lane Signal Controlled Junction 504405 440731 504405 440731 Junction with Boothferry Road/Rawcliffe 45900028 AIRMYN ROAD GOOLE Road/Lansdown Road Signal Controlled Junction 473655 424058 473655 424058 Pedestrian Crossings And 45900028 AIRMYN ROAD GOOLE O/S School Playing Fields Traffic Signals 473602 424223 473602 424223 45900028 AIRMYN ROAD GOOLE O/S West Park Zebra Crossing 473522 424468 473522 424468 45904574 ANDERSEN ROAD GOOLE Junction with Rawcliffe Road Signal Controlled Junction 473422 423780 473422 423780 45908280 BEMPTON LANE BRIDLINGTON Junction with Marton Road Signal Controlled Junction 518127 468400 518127 468400 45905242 BENTLEY LANE WALKINGTON Junction with East End/Mill Lane/Broadgate Signal Controlled Junction 500447 437412 500447 437412 45904601 BESSINGBY HILL BRIDLINGTON Junction with Bessingby Road/Driffield Road Signal Controlled Junction 516519 467045 516519 467045 45903639 BESSINGBY ROAD BRIDLINGTON Junction with Driffield Road/Besingby Hill Signal Controlled Junction 516537 467026 516537 467026 45903639 BESSINGBY ROAD BRIDLINGTON Junction with Thornton Road Signal Controlled Junction 516836 466936 516867 466910 45903639 BESSINGBY ROAD BRIDLINGTON O/S Bridlington Fire Station Toucan Crossing 517083 466847 517083 466847 45903639 BESSINGBY ROAD BRIDLINGTON Junction with Kingsgate Signal Controlled Junction 517632 466700 517632 466700 Junction -

Hull Cycle Map and Guide

Hull Cycles M&G 14/03/2014 11:42 Page 1 Why Cycle? Cycle Across Britain Ride Smart, Lock it, Keep it Cycle Shops in the Hull Area Sustrans is the UK’s leading Bike-fix Mobile Repair Service 07722 N/A www.bike-fix.co.uk 567176 For Your Health Born from Yorkshire hosting the Tour de France Grand Départ, the sustainable transport charity, working z Regular cyclists are as fit as a legacy, Cycle Yorkshire, is a long-term initiative to encourage everyone on practical projects so people choose Repair2ride Mobile Repair Service 07957 N/A person 10 years younger. to cycle and cycle more often. Cycling is a fun, cheap, convenient and to travel in ways that benefit their health www.repair2ride.co.uk 026262 z Physically active people are less healthy way to get about. Try it for yourself and notice the difference. and the environment. EDITION 10th likely to suffer from heart disease Bob’s Bikes 327a Beverley Road 443277 H8 1 2014 Be a part of Cycle Yorkshire to make our region a better place to live www.bobs-bikes.co.uk or a stroke than an inactive and work for this and future generations to come. Saddle up!! The charity is behind many groundbreaking projects including the National Cycle Network, over twelve thousand miles of traffic-free, person. 2 Cliff Pratt Cycles 84 Spring Bank 228293 H9 z Cycling improves your strength, For more information visit www.cycleyorkshire.com quiet lanes and on-road walking and cycling routes around the UK. www.cliffprattcycles.co.uk stamina and aerobic fitness. -

22 Lowerdale, Elloughton £269,950

22 Lowerdale, Elloughton £269,950 Truly superb extended and vastly improved 4 M62 motorway lying approximately ten miles This open plan room features laminated wood Bedroom/3 Bathroom Detached residence to the West of Hull. A main line train station flooring, radiator. Leads into: with west facing rear garden - fabulous - view with Inter City service is located in Brough, SITTING ROOM 11'9 x 11'4 (3.58m x 3.45m) before sold!! only a short driving distance away. Brough This superbly designed extension features offers more extensive facilities including a INTRODUCTION corner windows to two elevations, french supermarket. Leisure facilities abound with We are delighted to offer this superb family doors leading on to a large patio area, two Golf Clubs in close proximity, Ionians home. Extended to both floors by the present laminated wood flooring, ceiling spotlighting, Rugby Club within the village boundary, and owners and presenting a stylish living radiator. many accessible country walks including environment featuring a new Master Bedroom Brantingham Dale and the Wolds Way. GALLERIED LANDING Suite with Dressing Area & En-Suite, new A delightful airy Landing with radiator and Sitting Room, Living Room, open plan Dining ENTRANCE HALL airing cupboard offers access to two Suites, Room, refitted Breakfast Kitchen, Cloakroom/ A most impressive Hall offers access to two further Bedrooms and a Bathroom. WC, second Bedroom Suite with En-Suite, 2 staircase leading to a galleried Landing. The further Bedrooms (1 fitted), refitted Bathroom. Hall offers laminated wood flooring and BREAKFAST KITCHEN 14'2 x 11' (4.32m x Good sized west facing garden and side drive radiator. -

Service 78/277

Bus Timetables Service X46/X47 Service: Hull – Beverley – Market Weighton – Pocklington - York Operated by: East Yorkshire Motor Services Monday - Friday (From 29/9/19) Service X47 X46 X46 X46 X46 X46 X46 X46 X46 X46 X46 X46 X46 X46 Hull Interchange …. 0615 0635 0720 0830 0930 1030 1130 1230 1330 1430 1530 1630 1730 Newland Haworth Street …. 0623 0643 0729 0841 0941 1041 1141 1241 1341 1441 1543 1644 1744 Beverley Road Tesco …. 0629 0649 0735 0847 0947 1047 1147 1247 1347 1447 1550 1652 1752 Beverley Normandy Avenue …. 0638 0658 0745 0857 0957 1057 1157 1257 1357 1457 1600 1702 1802 Beverley Bus Station …. 0647 0707 0757 0907 1007 1107 1207 1307 1407 1507 1612 1717 1817 Bishop Burton …. 0655 0715 0805 0915 1015 1115 1215 1315 1415 1515 1620 1725 1825 Market Weighton Sancton Road …. 0707 0727 0817 0927 1027 1127 1227 1327 1427 1527 1632 1737 1837 Market Weighton Griffin …. 0710 0730 0822 0932 1032 1132 1232 1332 1432 1532 1637 1742 1842 Shiptonthorpe …. 0717 0737 0829 0937 1037 1137 1237 1337 1437 1537 1642 1747 1847 Hayton Green …. 0720 0740 0832 0940 1040 1140 1240 1340 1440 1540 1645 1750 1850 Pocklington Bus Station 0555 0730 0745 0840 0950 1050 1150 1250 1350 1450 1550 1655 1800 1900 Barmby Moor 0600 …. …. …. …. …. …. …. …. …. …. …. …. …. Wilberfoss Post Office 0606 …. …. …. …. …. …. …. …. …. …. …. …. …. Kexby Bridge 0609 0742 …. 0852 1002 1102 1202 1302 1402 1502 1602 1707 1812 1912 Osbaldwick Pinelands Way 0617 0757 …. 0907 1012 1112 1212 1312 1412 1512 1612 1717 1820 1920 York Piccadilly 0625 0812 …. 0922 1022 1122 1222 1322 1422 1522 1622 1727 1828 1928 York Railway Station 0635 0826 …. -

Roads Turnpike Trusts Eastern Yorkshire

E.Y. LOCAL HISTORY SERIES: No. 18 ROADS TURNPIKE TRUSTS IN EASTERN YORKSHIRE br K. A. MAC.\\AHO.' EAST YORKSHIRE LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY 1964 Ffve Shillings Further topies of this pamphlet (pnce ss. to members, 5s. to wm members) and of others in the series may be obtained from the Secretary.East Yorkshire Local History Society, 2, St. Martin's Lane, Mitklegate, York. ROADS AND TURNPIKE TRUSTS IN EASTERN YORKSHIRE by K. A. MACMAHON, Senior Staff Tutor in Local History, The University of Hull © East YQrk.;hiT~ Local History Society '96' ROADS AND TURNPIKE TRUSTS IN EASTERN YORKSHIRE A major purpose of this survey is to discuss the ongms, evolution and eventual decline of the turnpike trusts in eastern Yorkshire. The turnpike trust was essentially an ad hoc device to ensure the conservation, construction and repair of regionaIly important sections of public highway and its activities were cornple menrary and ancillary to the recognised contemporary methods of road maintenance which were based on the parish as the adminis trative unit. As a necessary introduction to this theme, therefore, this essay will review, with appropriate local and regional illustration, certain major features ofroad history from medieval times onwards, and against this background will then proceed to consider the history of the trusts in East Yorkshire and the roads they controlled. Based substantially on extant record material, notice will be taken of various aspects of administration and finance and of the problems ofthe trusts after c. 1840 when evidence oftheir decline and inevit able extinction was beginning to be apparent. .. * * * Like the Romans two thousand years ago, we ofthe twentieth century tend to regard a road primarily as a continuous strip ofwel1 prepared surface designed for the easy and speedy movement ofman and his transport vehicles. -

2021 Air Quality Annual Status Report (ASR)

2021 Air Quality Annual Status Report (ASR) In fulfilment of Part IV of the Environment Act 1995 Local Air Quality Management Date: June, 2021 East Riding of Yorkshire Council Information East Riding of Yorkshire Council Details Local Authority Officer Jon Tait Department Environmental Control Address Public Protection East Riding of Yorkshire Council Church Street Goole East Riding of Yorkshire DN14 5BG Telephone 01482 396207 E-mail [email protected] Report Reference Number LAQM ASR 2021 Date June 2021 LAQM Annual Status Report 2021 Executive Summary: Air Quality in Our Area Air Quality in East Riding of Yorkshire Air pollution is associated with a number of adverse health impacts. It is recognised as a contributing factor in the onset of heart disease and cancer. Additionally, air pollution particularly affects the most vulnerable in society: children, the elderly, and those with existing heart and lung conditions. There is also often a strong correlation with equalities issues because areas with poor air quality are also often less affluent areas1,2. The mortality burden of air pollution within the UK is equivalent to 28,000 to 36,000 deaths at typical ages3, with a total estimated healthcare cost to the NHS and social care of £157 million in 20174. Figure 1– Map of the East Riding of Yorkshire 1 Public Health England. Air Quality: A Briefing for Directors of Public Health, 2017 2 Defra. Air quality and social deprivation in the UK: an environmental inequalities analysis, 2006 3 Defra. Air quality appraisal: damage cost guidance, July 2020 4 Public Health England. Estimation of costs to the NHS and social care due to the health impacts of air pollution: summary report, May 2018 LAQM Annual Status Report 2021 i The East Riding of Yorkshire is located in the north of England on the East Coast approximately 200 miles from Edinburgh, London and Rotterdam. -

Matters to Be Specified in Section 15 Proposals to Discontinue a School

MATTERS TO BE SPECIFIED IN SECTION 15 PROPOSALS TO DISCONTINUE A SCHOOL Extract of Schedule 4 to The School Organisation (Establishment and Discontinuance of Schools)(England) Regulations 2007 (as amended): Contact details 1. The name of the LA or governing body publishing the proposals, and a contact address, and the name of the school it is proposed that should be discontinued. East Riding of Yorkshire Council, County Hall, Beverley, East Riding of Yorkshire, HU17 9BA Dunswell Primary School Implementation 2. The date when it is planned that the proposals will be implemented, or, where the proposals are to be implemented in stages, information about each stage and the date on which each stage is planned to be implemented. 31 August 2014 Consultation 3. A statement to the effect that all applicable statutory requirements to consult in relation to the proposals were complied with. All statutory requirements for consultation have been adhered to. 4. Evidence of the consultation before the proposals were published including: a) a list of persons and/or parties who were consulted; b) minutes of all public consultation meetings; c) the views of the persons consulted;and d) copies of all consultation documents and a statement of how these were made available. a) The consultation has included: Staff, Governors and parents of children attending Dunswell Primary School Staff, Governors and parents of children attending Woodmansey CE VC Primary School Ward Councillors Dunswell Parish Council 1 Woodmansey Parish Council David Davis MP Cottingham High School Beverley High School Beverley Grammar School Trades Unions and professional associations York Diocesan Board of Education b)Minutes of the public consultation meetings are attached as Appendix 1.