The Sale of Horses and Horse Interests: a Transactional Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Sky Miss (2020)

TesioPower Rancho San Antonio 2020 Sky Miss (2020) Caro Fortino II 4 Siberian Express Chambord 3 Indian Call Warfare 4 In Excess (1987) La Morlaye 13 Saulingo Sing Sing 13 Kantado Saulisa 3-i Vi Vilmorin 7-d Indian Charlie (1995) Dotterel 4-n Sovereign Dancer NORTHERN DANCER 2 Leo Castelli Bold Princess 5 Suspicious Native RAISE A NATIVE 8 Soviet Sojourn (1989) Be Suspicious 4-n Diplomat Way NASHUA 3 Political Parfait Jandy 22-c Peach Butter Creme Dela Creme A4 Uncle Mo (2008) Slipping Round 21-a Roberto Hail To Reason 4-n Kris S Bramalea 12 Sharp Queen PRINCEQUILLO 1 Arch (1995) Bridgework 10-a Danzig NORTHERN DANCER 2 Aurora Pas De Nom 7 Althea Alydar 9 Playa Maya (2000) Courtly Dee A4 NORTHERN DANCER Nearctic 14 Dixieland Band Natalma 2 Mississippi Mud Delta Judge 12 Dixie Slippers (1995) Sand Buggy 4-m CYANE TURN-TO 1 Cyane's Slippers Your Game 16-b Hot Slippers Rollicking 4 Uncle Brennie (2013) Miss Fairfield 8-c Bold Reasoning Boldnesian 4 Seattle Slew Reason To Earn 1-k My Charmer Poker 1 A P Indy (1989) Fair Charmer 13-c Secretariat BOLD RULER 8 Weekend Surprise SOMETHINGROYAL 2 Lassie Dear Buckpasser 1 Malibu Moon (1997) Gay Missile 3-l RAISE A NATIVE NATIVE DANCER 5 MR PROSPECTOR Raise You 8 Gold Digger NASHUA 3 Macoumba (1992) Sequence 13-c Green Dancer Nijinsky II 8 Maximova Green Valley 16-c Baracala Swaps A4 Moon Music (2007) Seximee 2-s RAISE A NATIVE NATIVE DANCER 5 MR PROSPECTOR Raise You 8 Gold Digger NASHUA 3 Smart Strike (1992) Sequence 13-c Smarten CYANE 16 Classy 'n Smart Smartaire A13 No Class Nodouble A1 Strike -

The Formation and Early History of the Knights of Ak-Sar-Ben As Shown by Omaha Newspapers

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 11-1-1962 The formation and early history of the Knights of Ak-Sar-Ben as shown by Omaha newspapers Arvid E. Nelson University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Nelson, Arvid E., "The formation and early history of the Knights of Ak-Sar-Ben as shown by Omaha newspapers" (1962). Student Work. 556. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/556 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. r m formation t m im u t m s toot of THE KNIQHTS OF A&~SAR-BBK AS S H O M nr OSAKA NEWSPAPERS A Thaoia Praaentad to the Faculty or tha Dapartmant of History Runic1pal University of Omaha In Partial Fulfilimant of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Art# by Arvld & liaison Ur. November 1^62 UMI Number: EP73194 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI EP73194 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. -

Omaha Beach out of Derby with Entrapped Epiglottis

THURSDAY, MAY 2, 2019 WEDNESDAY’S TRACKSIDE DERBY REPORT OMAHA BEACH OUT OF by Steve Sherack DERBY WITH ENTRAPPED LOUISVILLE, KY - With the rising sun making its way through partly cloudy skies, well before the stunning late scratch of likely EPIGLOTTIS favorite Omaha Beach (War Front) rocked the racing world, the backstretch at Churchill Downs was buzzing on a warm and breezy Wednesday morning ahead of this weekend’s 145th GI Kentucky Derby. Two of Bob Baffert’s three Derby-bound ‘TDN Rising Stars’ Roadster (Quality Road) and Improbable (City Zip) were among the first to step foot on the freshly manicured surface during the special 15-minute training window reserved for Derby/Oaks horses at 7:30 a.m. Champion and fellow ‘Rising Star’ Game Winner (Candy Ride {Arg}) galloped during a later Baffert set at 9 a.m. Cont. p3 IN TDN EUROPE TODAY Omaha Beach & exercise rider Taylor Cambra Wednesday morning. | Sherackatthetrack CALYX SENSATIONAL IN ROYAL WARM-UP Calyx (GB) (Kingman {GB}) was scintillating in Ascot’s Fox Hill Farms’s Omaha Beach (War Front), the 4-1 favorite for G3 Pavilion S. on Wednesday. Saturday’s GI Kentucky Derby Presented by Woodford Reserve, Click or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. will be forced to miss the race after it was discovered that he has an entrapped epiglottis. “After training this morning we noticed him cough a few times,” Hall of Fame trainer Richard Mandella said. “It caused us to scope him and we found an entrapped epiglottis. We can’t fix it this week, so we’ll have to have a procedure done in a few days and probably be out of training for three weeks. -

A Potential Pitfall for the Unsuspecting Purchaser of Repossessed Collateral

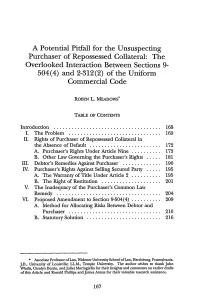

A Potential Pitfall for the Unsuspecting Purchaser of Repossessed Collateral: The Overlooked Interaction Between Sections 9- 504(4) and 2-312(2) of the Uniform Commercial Code ROBYN L. MEADOWS* TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . .................................... 168 I. The Problem . ............................... 169 II. Rights of Purchaser of Repossessed Collateral in the Absence of Default ........................ 172 A. Purchaser's Rights Under Article Nine .......... 173 B. Other Law Governing the Purchaser's Rights ..... 181 III. Debtor's Remedies Against Purchaser ............. 190 IV. Purchaser's Rights Against Selling Secured Party ..... 195 A. The Warranty of Title Under Article 2 .......... 195 B. The Right of Restitution .................... 201 V. The Inadequacy of the Purchaser's Common Law Remedy . ................................... 204 VI. Proposed Amendment to Section 9-504(4) .......... 209 A. Method for Allocating Risks Between Debtor and Purchaser ............................... 210 B. Statutory Solution ......................... 216 * Associate Professor of Law, Widener University School of Law, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. J.D., University of Louisville; LL.M., Temple University. The author wishes to thank John Wiadis, Carolyn Dessin, andJuliet Moringiello for their insights and comments on earlier drafts of this Article and Ronald Phillips and James Annas for their valuable research assistance. THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 44:167 INTRODUCTION Under the provisions of the Uniform Commercial Code (the Code), -

Bridging the Gap: Curlin=S Turf Frontier

FRIDAY, 15 FEBRUARY 2019 BLUE ON POINT AT MEYDAN BRIDGING THE GAP: By Kelsey Riley = Last year=s G1 King=s Stand S. winner Blue Point (Shamardal) CURLIN S TURF FRONTIER towered above his G2 Meydan Sprint rivals on paper, and he ran to form on Thursday to win eased down by five lengths on seasonal debut. The 5-year-old will now target the G1 Al Quoz Sprint on Mar. 30. He was scratched behind the gate of that contest last year as the favourite after blood was discovered in his nostrils. Rerouted to Hong Kong=s G1 Chairman=s Sprint Prize over six furlongs a month later, the >TDN Rising Star= trailed home last of nine but he looked much more like himself back to five furlongs in the King=s Stand in June, winning by 1 3/4 lengths from the highly regarded Battaash (Ire) (Dark Angel {Ire}). Back up to six for the July Cup, he was beaten 4 3/4 lengths in seventh and was 2 1/4 lengths off the near dead heat of Alpha Delphini (GB) (Captain Gerrard {Ire}) and Mabs Cross (GB) (Dutch Art {GB}) when third when last seen in the G1 Nunthorpe S. in August. Sitting back in third on Thursday as Faatinah (Aus) (Nicconi Curlin has been chosen as the first mate {Aus})Bhis closest-rated rival and the winner of a handicap over for Lady Aurelia | Sarah Andrew this track and trip on Jan. 3Bset the pace, Blue Point responded when given a shake of the reins by William Buick at the 300- meter mark. -

Constitution Colt Lays Down the Law in Curlin Florida

SUNDAY, MARCH 29, 2020 CONSTITUTION COLT AQUEDUCT GETS HOSPITAL GO AHEAD; RACING WONT RESUME FOR WINTER OR LAYS DOWN THE LAW SPRING MEETS IN CURLIN FLORIDA DERBY Aqueduct will be re-purposed as a temporary hospital, and racing will not resume there again at the winter or spring meets, according to a press release from the New York Racing Association Saturday afternoon. When racing does resume, it is expected to be at Belmont Park, which is currently scheduled to open Apr. 24. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo raised the possibility of making Aqueduct a temporary hospital at his press briefing Friday, and said he would seek the required permission from the federal government to serve the borough of Queens with a 1,000-plus patient overflow facility at the track. Cuomo has set a goal for New York State to provide COVID-19 patient overflow facilities in each New York City borough as well as Westchester, Rockland, Nassau and Suffolk counties. Cont. p5 IN TDN EUROPE TODAY Tiz the Law | Lauren King LOPE DE VEGA THE PLAN FOR BATTAASH DAM Sackatoga Stable=s Tiz the Law (Constitution) dominated a Amy Lynam speaks with Paul McCartan on Ballyphilip Stud’s 2020 talented field at Gulfstream in Saturday=s GI Curlin Florida Derby mating plans. Lope de Vega (Ire) is the mate of Anna Law (Ire) (Lawman {Fr}), herself the dam of MG1SW Battash (Ire) (Dark Angel to cement his status as one of the top contenders for the {Ire}). Click or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. GI Kentucky Derby, which was recently moved to the First Saturday in September. -

Setting the Standard

SETTING THE STANDARD A century ago a colt bred by Hamburg Place won a trio of races that became known as the Triple Crown, a feat only 12 others have matched By Edward L. Bowen COOK/KEENELAND LIBRARY Sir Barton’s exploits added luster to America’s classic races. 102 SPRING 2019 K KEENELAND.COM SirBarton_Spring2019.indd 102 3/8/19 3:50 PM BLACK YELLOWMAGENTACYAN KM1-102.pgs 03.08.2019 15:55 Keeneland Sir Barton, with trainer H. Guy Bedwell and jockey John Loftus, BLOODHORSE LIBRARY wears the blanket of roses after winning the 1919 Kentucky Derby. KEENELAND.COM K SPRING 2019 103 SirBarton_Spring2019.indd 103 3/8/19 3:50 PM BLACK YELLOWMAGENTACYAN KM1-103.pgs 03.08.2019 15:55 Keeneland SETTING THE STANDARD ir Barton is renowned around the sports world as the rst Triple Crown winner, and 2019 marks the 100th an- niversary of his pivotal achievement in SAmerican horse racing history. For res- idents of Lexington, Kentucky — even those not closely attuned to racing — the name Sir Barton has an addition- al connotation, and a local one. The street Sir Barton Way is prominent in a section of the city known as Hamburg. Therein lies an additional link with history, for Sir Barton sprung from the famed Thoroughbred farm also known as Hamburg Place, which occupied the same land a century ago. The colt Sir Barton was one of four Kentucky Derby winners bred at Hamburg Place by a master of the Turf, one John E. Madden. Like the horse’s name, the name Madden also has come down through the years in a milieu of lasting and regen- erating fame. -

2018 Media Guide NYRA.Com 1 FIRST RUNNING the First Running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park Took Place on a Thursday

2018 Media Guide NYRA.com 1 FIRST RUNNING The first running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park took place on a Thursday. The race was 1 5/8 miles long and the conditions included “$200 each; half forfeit, and $1,500-added. The second to receive $300, and an English racing saddle, made by Merry, of St. James TABLE OF Street, London, to be presented by Mr. Duncan.” OLDEST TRIPLE CROWN EVENT CONTENTS The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is the oldest of the Triple Crown events. It predates the Preakness Stakes (first run in 1873) by six years and the Kentucky Derby (first run in 1875) by eight. Aristides, the winner of the first Kentucky Derby, ran second in the 1875 Belmont behind winner Calvin. RECORDS AND TRADITIONS . 4 Preakness-Belmont Double . 9 FOURTH OLDEST IN NORTH AMERICA Oldest Triple Crown Race and Other Historical Events. 4 Belmont Stakes Tripped Up 19 Who Tried for Triple Crown . 9 The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is one of the oldest stakes races in North America. The Phoenix Stakes at Keeneland was Lowest/Highest Purses . .4 How Kentucky Derby/Preakness Winners Ran in the Belmont. .10 first run in 1831, the Queens Plate in Canada had its inaugural in 1860, and the Travers started at Saratoga in 1864. However, the Belmont, Smallest Winning Margins . 5 RUNNERS . .11 which will be run for the 150th time in 2018, is third to the Phoenix (166th running in 2018) and Queen’s Plate (159th running in 2018) in Largest Winning Margins . -

The Triple Crown (1867-2019)

The Triple Crown (1867-2019) Kentucky Derby Winner Preakness Stakes Winner Belmont Stakes Winner Horse of the Year Jockey Jockey Jockey Champion 3yo Trainer Trainer Trainer Year Owner Owner Owner 2019 Country House War of Will Sir Winston Bricks and Mortar Flavien Prat Tyler Gaffalione Joel Rosario Maximum Security Bill Mott Mark Casse Mark Casse Mrs. J.V. Shields Jr., E.J.M. McFadden Jr. & LNJ Foxwoods Gary Barber Tracy Farmer 2018 Justify Justify Justify Justify Mike Smith Mike Smith Mike Smith Justify Bob Baffert Bob Baffert Bob Baffert WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC 2017 Always Dreaming Cloud Computing Tapwrit Gun Runner John Velazquez Javier Castellano Joel Ortiz West Coast Todd Pletcher Chad Brown Todd Pletcher MeB Racing, Brooklyn Boyz, Teresa Viola, St. Elias, Siena Farm & West Point Thoroughbreds Bridlewood Farm, Eclipse Thoroughbred Partners & Robert V. LaPenta Klaravich Stables Inc. & William H. Lawrence 2016 Nyquist Exaggerator Creator California Chrome Mario Gutierrez Kent Desormeaux Irad Ortiz Jr. Arrogate Doug O’Neill Keith Desormeaux Steve Asmussen Big Chief Racing, Head of Plains Partners, Rocker O Ranch, Keith Desormeaux Reddam Racing LLC (J. Paul Reddam) WinStar Farm LLC & Bobby Flay 2015 American Pharoah American Pharoah American Pharoah American Pharoah Victor Espinoza Victor Espinoza Victor Espinoza American Pharoah Bob Baffert Bob Baffert Bob Baffert Zayat Stables LLC (Ahmed Zayat) Zayat Stables LLC (Ahmed Zayat) Zayat Stables LLC (Ahmed Zayat) 2014 California Chrome California Chrome Tonalist California Chrome Victor Espinoza Victor Espinoza Joel Rosario California Chrome Art Sherman Art Sherman Christophe Clement Steve Coburn & Perry Martin Steve Coburn & Perry Martin Robert S. -

Chestnut Filly Barn 3 Hip No

Consigned by Parrish Farms, Agent Barn Hip No. 3 Chestnut Filly 613 Storm Bird Storm Cat ......................... Terlingua Bluegrass Cat ................... A.P. Indy She's a Winner ................. Chestnut Filly Get Lucky February 4, 2008 Fappiano Unbridled.......................... Gana Facil Unbridled Lady ................. (1996) Assert (IRE) Assert Lady....................... Impressive Lady By BLUEGRASS CAT (2003). Black-type winner of $1,761,280, Haskell In- vitational S. [G1] (MTH, $600,000), Remsen S. [G2] (AQU, $120,000), Nashua S. [G3] (BEL, $67,980), Sam F. Davis S. [L] (TAM, $60,000), 2nd Kentucky Derby [G1] (CD, $400,000), Belmont S. [G1] (BEL, $200,000), Travers S. [G1] (SAR, $200,000), Tampa Bay Derby [G3] (TAM, $50,000). Brother to black-type winner Sonoma Cat, half-brother to black-type win- ner Lord of the Game. His first foals are 2-year-olds of 2010. 1st dam UNBRIDLED LADY, by Unbridled. 4 wins at 3 and 4, $196,400, Geisha H.-R (PIM, $60,000), 2nd Carousel S. [L] (LRL, $10,000), Geisha H.-R (PIM, $20,000), Moonlight Jig S.-R (PIM, $8,000), 3rd Maryland Racing Media H. [L] (LRL, $7,484), Squan Song S.-R (LRL, $5,500). Dam of 6 other registered foals, 5 of racing age, 5 to race, 2 winners-- Forestelle (f. by Forestry). 3 wins at 3 and 4, 2009, $63,654. Sun Pennies (f. by Speightstown). Winner in 2 starts at 3, 2010, $21,380. Mared (c. by Speightstown). Placed at 2 and 3, 2009 in Qatar; placed at 3, 2009 in England. 2nd dam ASSERT LADY, by Assert (IRE). -

The Triple Crown (1867-2020)

The Triple Crown (1867-2020) Kentucky Derby Winner Preakness Stakes Winner Belmont Stakes Winner Horse of the Year Jockey Jockey Jockey Champion 3yo Trainer Trainer Trainer Year Owner Owner Owner 2020 Authentic (Sept. 5, 2020) f-Swiss Skydiver (Oct. 3, 2020) Tiz the Law (June 20, 2020) Authentic John Velazquez Robby Albarado Manny Franco Authentic Bob Baffert Kenny McPeek Barclay Tagg Spendthrift Farm, MyRaceHorse Stable, Madaket Stables & Starlight Racing Peter J. Callaghan Sackatoga Stable 2019 Country House War of Will Sir Winston Bricks and Mortar Flavien Prat Tyler Gaffalione Joel Rosario Maximum Security Bill Mott Mark Casse Mark Casse Mrs. J.V. Shields Jr., E.J.M. McFadden Jr. & LNJ Foxwoods Gary Barber Tracy Farmer 2018 Justify Justify Justify Justify Mike Smith Mike Smith Mike Smith Justify Bob Baffert Bob Baffert Bob Baffert WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC 2017 Always Dreaming Cloud Computing Tapwrit Gun Runner John Velazquez Javier Castellano Joel Ortiz West Coast Todd Pletcher Chad Brown Todd Pletcher MeB Racing, Brooklyn Boyz, Teresa Viola, St. Elias, Siena Farm & West Point Thoroughbreds Bridlewood Farm, Eclipse Thoroughbred Partners & Robert V. LaPenta Klaravich Stables Inc. & William H. Lawrence 2016 Nyquist Exaggerator Creator California Chrome Mario Gutierrez Kent Desormeaux Irad Ortiz Jr. Arrogate Doug -

Greatest Honour Geared up for Curlin Florida Derby

ftboa.com • Friday • March 26, 2021 FEC/FTBOA PUBLICATION FLORIDA’SDAILYRACINGDIGEST FOR ADVERTISING INFORMATION or to subscribe, please call Antoinette at 352-732-8858 or email: [email protected] In This Issue: Al Quoz Sprint Could Be Quick Jump in Earnings for Extravagant Kid Sadler’s Joy Back for More Mucho Unusual Heads Solid Field of Distaffers in Santa Ana Stakes Mandatory Rainbow 6 Payout Set for Florida Derby Day Card Fulmini Returns to Stakes Company Greatest Honour/LAUREN KING PHOTO Greatest Honour Geared Up Gulfstream Park Charts for Curlin Florida Derby Florida Stallion Progeny List Florida Breeders’ List BY GULFSTREAM PARK “I’m looking forward to running him,” PRESS OFFICE ___________________ McGaughey said. “He’s been a pleasure all winter. He’s never missed a beat. Things Wire to Wire Business Place HALLANDALE BEACH, FL—Courtlandt have sort of been the same. We just hope it Farms’ Greatest Honour will have a lot continues.” going for him in Saturday’s $750,000 The mile-and-one-eighth Florida Featured Advertisers Curlin Florida Derby presented by Hill ‘n’ Derby, which has produced the winners of Baoma Corp Dale Farms at Xalapa (Grade 1). 60 Triple Crown events, will headline a Berrettini Feed The 3-year-old son of Tapit has shown a program with 10 stakes, including the Bloodstockauction USA distinct fondness for the Gulfstream Park $200,000 Gulfstream Park Oaks (G2) and Florida Department of Agriculture racetrack, over which he has won all three the $200,000 Pan American (G2) present- of his races during the Championship Meet. ed by Rood & Riddle.