Glider Handbook, Chapter 3: Aerodynamics of Flight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8. Level, Non-Accelerated Flight

Performance 8. Level, Non-Accelerated Flight For non-accelerated flight, the tangential acceleration, , and normal acceleration, . As a result, the governing equations become: (1) If we add the additional assumptions of level flight, , and that the thrust is aligned with the velocity vector, , then Eq. (1) reduces to the simple form: (2) The last two equations tell us that the altitude is a constant, and the velocity is the range rate. For now, however, we are interested in the first two equations that can be rewritten as: (3) The key thing to remember about these equations is that the weight,W,isagivenand it is equal to the Lift. Consequently, lift is not at our disposal, it must equal the given weight! Thus for a given aircraft and any given altitude, we can determine the required lift coefficient (and hence angle-of-attack) for any given airspeed. (4) Therefore at a given weight and altitude, the lift coefficient varies as 1 over V2. A sketch of lift coefficient vs. speed looks as follows: 1 It is clear from the figure that as the vehicle slows down, in order to remain in level flight, the lift coefficient (and hence angle-of-attack) must increase. [You can think of it in terms of the momentum flux. The momentum flux (the mass flow rate time the velocity out in the z direction) creates the lift force. Since the mass flow rate is directional proportional to the velocity, then the slower we go, the more the air must be deflected downward. We do this by increasing the angle-of-attack!]. -

Soaring Weather

Chapter 16 SOARING WEATHER While horse racing may be the "Sport of Kings," of the craft depends on the weather and the skill soaring may be considered the "King of Sports." of the pilot. Forward thrust comes from gliding Soaring bears the relationship to flying that sailing downward relative to the air the same as thrust bears to power boating. Soaring has made notable is developed in a power-off glide by a conven contributions to meteorology. For example, soar tional aircraft. Therefore, to gain or maintain ing pilots have probed thunderstorms and moun altitude, the soaring pilot must rely on upward tain waves with findings that have made flying motion of the air. safer for all pilots. However, soaring is primarily To a sailplane pilot, "lift" means the rate of recreational. climb he can achieve in an up-current, while "sink" A sailplane must have auxiliary power to be denotes his rate of descent in a downdraft or in come airborne such as a winch, a ground tow, or neutral air. "Zero sink" means that upward cur a tow by a powered aircraft. Once the sailcraft is rents are just strong enough to enable him to hold airborne and the tow cable released, performance altitude but not to climb. Sailplanes are highly 171 r efficient machines; a sink rate of a mere 2 feet per second. There is no point in trying to soar until second provides an airspeed of about 40 knots, and weather conditions favor vertical speeds greater a sink rate of 6 feet per second gives an airspeed than the minimum sink rate of the aircraft. -

Evaluation and Flight Assessment of a Scale Glider

Dissertations and Theses 8-2014 Evaluation and Flight Assessment of a Scale Glider Alvydas Anthony Civinskas Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University - Daytona Beach Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/edt Part of the Aerospace Engineering Commons Scholarly Commons Citation Civinskas, Alvydas Anthony, "Evaluation and Flight Assessment of a Scale Glider" (2014). Dissertations and Theses. 41. https://commons.erau.edu/edt/41 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Evaluation and Flight Assessment of a Scale Glider by Alvydas Anthony Civinskas A Thesis Submitted to the College of Engineering Department of Aerospace Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Aerospace Engineering Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Daytona Beach, Florida August 2014 Acknowledgements The first person I would like to thank is my committee chair Dr. William Engblom for all the help, guidance, energy, and time he put into helping me. I would also like to thank Dr. Hever Moncayo for giving up his time, patience, and knowledge about flight dynamics and testing. Without them, this project would not have materialized nor survived the many bumps in the road. Secondly, I would like to thank the RC pilot Daniel Harrison for his time and effort in taking up the risky and stressful work of piloting. Individuals like Jordan Beckwith and Travis Billette cannot be forgotten for their numerous contributions in getting the motor test stand made and helping in creating the air data boom pod so that test data. -

Ff 89/6 Copy

$3 vol libre • free flight 6/89 Dec - Jan POTPOURRI SAC was informed by Sport Canada on the 10th of July that we are not eligible for funding for 1989-90 and until further notice. Thus we are now totally on our own. The average yearly grant from 1979 to 1988 in 1989 dollars was $14,000, or $16 per person. Perhaps it’s a good thing as planning in an atmosphere of doubt is not conducive to good health and efficient use of funds. The cutback was not unexpected and steps were taken early on to ease the effects of this loss of revenue. Imaginative planning in our small store and a good response from our members through the use of the “Soaring Stuff” inserts resulted in in- creased sales. We will also receive higher than projected invest- ment income essentially due to careful cash management and short-term interest rates, which have remained higher for longer than generally expected. In addition, a small gain in projected receipts from an unexpected increase in membership – now at 1423 – which is the first time since 1982 that we have passed 1400. Total expenditures should come in well below budget projection, primarily as a result of scaling back meetings and travel expenditures. On balance it seems fair to say that a combination of some tight fistedness on the expenditure side and a bit of luck on the revenue side will leave SAC in a financially stronger position than was expected at the beginning of the season, despite the cutting off of govern- ment funding. -

Ai2019-2 Aircraft Serious Incident Investigation Report

AI2019-2 AIRCRAFT SERIOUS INCIDENT INVESTIGATION REPORT ACADEMIC CORPORATE BODY JAPAN AVIATION ACADEMY J A 2 4 5 1 March 28, 2019 The objective of the investigation conducted by the Japan Transport Safety Board in accordance with the Act for Establishment of the Japan Transport Safety Board and with Annex 13 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation is to prevent future accidents and incidents. It is not the purpose of the investigation to apportion blame or liability. Kazuhiro Nakahashi Chairman Japan Transport Safety Board Note: This report is a translation of the Japanese original investigation report. The text in Japanese shall prevail in the interpretation of the report. AIRCRAFT SERIOUS INCIDENT INVESTIGATION REPORT INABILITY TO OPERATE DUE TO DAMAGE TO LANDING GEAR DURING FORCED LANDING ON A GRASSY FIELD ABOUT 3 KM SOUTHWEST OF NOTO AIRPORT, JAPAN AT ABOUT 15:00 JST, SEPTEMBER 26, 2018 ACADEMIC CORPORATE BODY JAPAN AVIATION ACADEMY VALENTIN TAIFUN 17EII (MOTOR GLIDER: TWO SEATER), JA2451 February 22, 2019 Adopted by the Japan Transport Safety Board Chairman Kazuhiro Nakahashi Member Toru Miyashita Member Toshiyuki Ishikawa Member Yuichi Marui Member Keiji Tanaka Member Miwa Nakanishi 1. PROCESS AND PROGRESS OF THE INVESTIGATION 1.1 Summary of On Wednesday, September 26, 2018, a Valentin Taifun 17EII (motor the Serious glider), registered JA2451, owned by Japan Aviation Academy, took off from Incident Noto Airport in order to make a test flight before the airworthiness inspection. During the flight, as causing trouble in its electric system, the aircraft tried to return to Noto Airport by gliding, but made a forced landing on a grassy field about 3 km short of Noto Airport, and sustained damage to the landing gear, therefore, the operation of the aircraft could not be continued. -

AMA FPG-9 Glider OBJECTIVES – Students Will Learn About the Basics of How Flight Works by Creating a Simple Foam Glider

AEX MARC_Layout 1 1/10/13 3:03 PM Page 18 activity two AMA FPG-9 Glider OBJECTIVES – Students will learn about the basics of how flight works by creating a simple foam glider. – Students will be introduced to concepts about air pressure, drag and how aircraft use control surfaces to climb, turn, and maintain stable flight. Activity Credit: Credit and permission to reprint – The Academy of Model Aeronautics (AMA) and Mr. Jack Reynolds, a volunteer at the National Model Aviation Museum, has graciously given the Civil Air Patrol permission to reprint the FPG-9 model plan and instructions here. More activities and suggestions for classroom use of model aircraft can be found by contacting the Academy of Model Aeronautics Education Committee at their website, buildandfly.com. MATERIALS • FPG-9 pattern • 9” foam plate • Scissors • Clear tape • Ink pen • Penny 18 AEX MARC_Layout 1 1/10/13 3:03 PM Page 19 BACKGROUND Control surfaces on an airplane help determine the movement of the airplane. The FPG-9 glider demonstrates how the elevons and the rudder work. Elevons are aircraft control surfaces that combine the functions of the elevator (used for pitch control) and the aileron (used for roll control). Thus, elevons at the wing trailing edge are used for pitch and roll control. They are frequently used on tailless aircraft such as flying wings. The rudder is the small moving section at the rear of the vertical stabilizer that is attached to the fixed sections by hinges. Because the rudder moves, it varies the amount of force generated by the tail surface and is used to generate and control the yawing (left and right) motion of the aircraft. -

Federal Aviation Administration, DOT § 61.45

Federal Aviation Administration, DOT Pt. 61 Vmcl Minimum Control Speed—Landing. 61.35 Knowledge test: Prerequisites and Vmu The speed at which the last main passing grades. landing gear leaves the ground. 61.37 Knowledge tests: Cheating or other VR Rotate Speed. unauthorized conduct. VS Stall Speed or minimum speed in the 61.39 Prerequisites for practical tests. stall. 61.41 Flight training received from flight WAT Weight, Altitude, Temperature. instructors not certificated by the FAA. 61.43 Practical tests: General procedures. END QPS REQUIREMENTS 61.45 Practical tests: Required aircraft and equipment. [Doc. No. FAA–2002–12461, 73 FR 26490, May 9, 61.47 Status of an examiner who is author- 2008] ized by the Administrator to conduct practical tests. PART 61—CERTIFICATION: PILOTS, 61.49 Retesting after failure. FLIGHT INSTRUCTORS, AND 61.51 Pilot logbooks. 61.52 Use of aeronautical experience ob- GROUND INSTRUCTORS tained in ultralight vehicles. 61.53 Prohibition on operations during med- SPECIAL FEDERAL AVIATION REGULATION NO. ical deficiency. 73 61.55 Second-in-command qualifications. SPECIAL FEDERAL AVIATION REGULATION NO. 61.56 Flight review. 100–2 61.57 Recent flight experience: Pilot in com- SPECIAL FEDERAL AVIATION REGULATION NO. mand. 118–2 61.58 Pilot-in-command proficiency check: Operation of an aircraft that requires Subpart A—General more than one pilot flight crewmember or is turbojet-powered. Sec. 61.59 Falsification, reproduction, or alter- 61.1 Applicability and definitions. ation of applications, certificates, 61.2 Exercise of Privilege. logbooks, reports, or records. 61.3 Requirement for certificates, ratings, 61.60 Change of address. -

Fly-By-Wire - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 11-8-20 下午5:33 Fly-By-Wire from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Fly-by-wire - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 11-8-20 下午5:33 Fly-by-wire From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Fly-by-wire (FBW) is a system that replaces the Fly-by-wire conventional manual flight controls of an aircraft with an electronic interface. The movements of flight controls are converted to electronic signals transmitted by wires (hence the fly-by-wire term), and flight control computers determine how to move the actuators at each control surface to provide the ordered response. The fly-by-wire system also allows automatic signals sent by the aircraft's computers to perform functions without the pilot's input, as in systems that automatically help stabilize the aircraft.[1] Contents Green colored flight control wiring of a test aircraft 1 Development 1.1 Basic operation 1.1.1 Command 1.1.2 Automatic Stability Systems 1.2 Safety and redundancy 1.3 Weight saving 1.4 History 2 Analog systems 3 Digital systems 3.1 Applications 3.2 Legislation 3.3 Redundancy 3.4 Airbus/Boeing 4 Engine digital control 5 Further developments 5.1 Fly-by-optics 5.2 Power-by-wire 5.3 Fly-by-wireless 5.4 Intelligent Flight Control System 6 See also 7 References 8 External links Development http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fly-by-wire Page 1 of 9 Fly-by-wire - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 11-8-20 下午5:33 Mechanical and hydro-mechanical flight control systems are relatively heavy and require careful routing of flight control cables through the aircraft by systems of pulleys, cranks, tension cables and hydraulic pipes. -

Hang Glider: Range Maximization the Problem Is to Compute the flight Inputs to a Hang Glider So As to Provide a Maximum Range flight

Hang Glider: Range Maximization The problem is to compute the flight inputs to a hang glider so as to provide a maximum range flight. This problem first appears in [1]. The hang glider has weight W (glider plus pilot), a lift force L acting perpendicular to its velocity vr relative to the air, and a drag force D acting in a direction opposite to vr. Denote by x the horizontal position of the glider, by vx the horizontal component of the absolute velocity, by y the vertical position, and by vy the vertical component of absolute velocity. The airmass is not static: there is a thermal just 250 meters ahead. The profile of the thermal is given by the following upward wind velocity: 2 2 − x −2.5 x u (x) = u e ( R ) 1 − − 2.5 . a m R We take R = 100 m and um = 2.5 m/s. Note, MKS units are used through- out. The upwind profile is shown in Figure 1. Letting η denote the angle between vr and the horizontal plane, we have the following equations of motion: 1 x˙ = vx, v˙x = m (−L sin η − D cos η), 1 y˙ = vy, v˙y = m (L cos η − D sin η − W ) with q vy − ua(x) 2 2 η = arctan , vr = vx + (vy − ua(x)) , vx 1 1 L = c ρSv2,D = c (c )ρSv2,W = mg. 2 L r 2 D L r The glider is controlled by the lift coefficient cL. The drag coefficient is assumed to depend on the lift coefficient as 2 cD(cL) = c0 + kcL where c0 = 0.034 and k = 0.069662. -

Prediction of Laminar/Turbulent Transition in Airfoil Flows

PREDICTION OF LAMINAR/TURBULENT TRANSITION IN AIRFOIL FLOWS by Jeppe Johansen and Jens Norkaer Sorensen DTU FLUID MECHANICS H ENERGY ENGINEERING TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY OF DENMARK / DANISH CENTER FOR APPLIED MATHEMATICS AND MECHANICS Scientific Council Poul Andersen Dept, of Naval Architecture and Offshore Engineering Martin P. Bends0e Dept, of Mathematics Ove Ditlevsen Dept, of Structural Engineering and Materials Ivar G. Jonsson Dept, of Hydrodynamics and Water Resources Wolfhard Kliem Dept, of Mathematics Steen Krenk Dept, of Structural Engineering and Materials P. Scheel Larsen Dept, of Energy Engineering Frithiof I. Niordson Dept, of Solid Mechanics Pauli Pedersen Dept, of Solid Mechanics P. Temdrup Pedersen Dept, of NavalArchitecture and Offshore Engineering- Dan Rosbjerg Dept. of Hydrodynamics and Water Resources Jens Nprkser Sprensen Dept, of Energy Engineering P. Grove Thomsen Dept, of Mathematical Modelling Hans True Dept, of Mathematical Modelling Viggo Tvergaard Dept, of Solid Mechanics Secretary Pauli Pedersen, Docent, Dr.techn. Department of Solid Mechanics, Building 404 Technical University of Denmark DK-2800 Lyngby, Denmark DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electronic image products. Images are produced from the best available original document. Prediction of Laminar/Turbulent Transition in Airfoil Flows Jeppe Johansen* and Jens N. Sprensen* * Ris0 National Laboratory, Denmark and * Department of Energy Engineering, Technical University of Denmark Presented as Paper 98-0702 at the AIAA 36th Aerospace Sciences Meeting Sc Exhibit, Reno, NV, January 12*15, 1998 tphD student, Wind Energy and Atmospheric Physics Department, Rise National Laboratory, DK-4000 RoskUde, Denmark * Associate Professor, Department of Energy Engineering, Technical University of Denmark, DK- 2800 Lyngby, Denmark 1 Abstract The prediction of the location of transition is important for low Reynolds number airfoil flows. -

Aerodyn Theory Manual

January 2005 • NREL/TP-500-36881 AeroDyn Theory Manual P.J. Moriarty National Renewable Energy Laboratory Golden, Colorado A.C. Hansen Windward Engineering Salt Lake City, Utah National Renewable Energy Laboratory 1617 Cole Boulevard, Golden, Colorado 80401-3393 303-275-3000 • www.nrel.gov Operated for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy by Midwest Research Institute • Battelle Contract No. DE-AC36-99-GO10337 January 2005 • NREL/TP-500-36881 AeroDyn Theory Manual P.J. Moriarty National Renewable Energy Laboratory Golden, Colorado A.C. Hansen Windward Engineering Salt Lake City, Utah Prepared under Task No. WER4.3101 and WER5.3101 National Renewable Energy Laboratory 1617 Cole Boulevard, Golden, Colorado 80401-3393 303-275-3000 • www.nrel.gov Operated for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy by Midwest Research Institute • Battelle Contract No. DE-AC36-99-GO10337 NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or any agency thereof. -

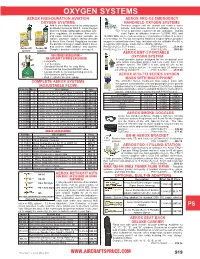

Oxygen Systems

OXYGEN SYSTEMS AEROX HIGH-DURATION AVIATION AEROX PRO-O2 EMERGENCY OXYGEN SYSTEMS HANDHELD OXYGEN SYSTEMS Add to your flying comfort by using oxygen Provides oxygen until the aircraft can reach a lower at altitudes as low as 5000 ft. Aerox Oxygen altitude. And because Pro-O2 is refillable, there is no CM Systems include lightweight aluminum cyl in- need to purchase replacement O2 cartridges. During ders, regulators, all hardware, flow meter, short flights at altitudes between 12,500ft. MSL and and nasal cannulas (masks available as 14,000ft. MSL where maneuvering over mountains or turbulent weather option). Oxysaver oxygen saving cannulas is necessary, the Pro-O2 emergency handheld oxygen system provides & Aerox Flow Control Regulators increase oxygen to extend these brief legs. Included with the refillable Pro-O2 is WP the duration of oxygen supply about 4 times, a regulator with gauge, mask and a refillable cylinder. and prevent nasal irritation and dryness. Pro-O2-2 (2 Cu. Ft./1 mask)........................P/N 13-02735 .........$328.00 Aerox 2D Aerox 4M Complete brochure available on request. Pro-O2-4 (2 Cu. Ft./2 masks) ......................P/N 13-02736 .........$360.00 system system AEROX EMT-3 PORTABLE 500 SERIES REGULATOR – AN AIRCRAFT SPRUCE EXCLUSIVE! OXYGEN SYSTEM ME A small portable system designed for the occasional user • Low profile who wants something smaller and less costly than a full • 1, 2, & 4 place portable system. The EMT-3 is also ideal for use as an • Standard Aircraft filler for easy filling emergency oxygen system. The system lasts 25 minutes at • Convenient top mounted ON/OFF valve 2.5 LPM @ 25,000 FT.