The Spock Paradox: Permissiveness, Control, and Dr. Spock's Advice For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resist Newsletter, Feb. 2, 1968

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Resist Newsletters Resist Collection 2-2-1968 Resist Newsletter, Feb. 2, 1968 Resist Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/resistnewsletter Recommended Citation Resist, "Resist Newsletter, Feb. 2, 1968" (1968). Resist Newsletters. 4. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/resistnewsletter/4 a call to resist illegitimate authority .P2bruar.1 2 , 1~ 68 -763 Maasaohuaetta A.Tenue, RH• 4, Caabrid«e, Jlaaa. 02139-lfewaletter I 5 THE ARRAIGNMENTS: Boston, Jan. 28 and 29 Two days of activities surrounded the arraignment for resistance activity of Spock, Coffin, Goodman, Ferber and Raskin. On Sunday night an 'Interfaith Service for Consci entious Dissent' was held at the First Church of Boston. Attended by about 700 people, and addressed by clergymen of the various faiths, the service led up to a sermon on 'Vietnam and Dissent' by Rev. William Sloane Coffin. Later that night, at Northeastern University, the major event of the two days, a rally for the five indicted men, took place. An overflow crowd of more than 2200 attended the rally,vhich was sponsored by a broad spectrum of organizations. The long list of speakers included three of the 'Five' - Spock (whose warmth, spirit, youthfulness, and toughness clearly delight~d an understandably sympathetic and enthusiastic aud~ence), Coffin, Goodman. Dave Dellinger of Liberation Magazine and the National Mobilization Co11111ittee chaired the meeting. The other speakers were: Professor H. Stuart Hughes of Ha"ard, co-chairman of national SANE; Paul Lauter, national director of RESIST; Bill Hunt of the Boston Draft Resistance Group, standing in for a snow-bound liike Ferber; Bob Rosenthal of Harvard and RESIST who announced the formation of the Civil Liberties Legal Defense Fund; and Tom Hayden. -

Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2017 Hippieland: Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood Kevin Mercer University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Mercer, Kevin, "Hippieland: Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5540. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5540 HIPPIELAND: BOHEMIAN SPACE AND COUNTERCULTURAL PLACE IN SAN FRANCISCO’S HAIGHT-ASHBURY NEIGHBORHOOD by KEVIN MITCHELL MERCER B.A. University of Central Florida, 2012 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the birth of the late 1960s counterculture in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. Surveying the area through a lens of geographic place and space, this research will look at the historical factors that led to the rise of a counterculture here. To contextualize this development, it is necessary to examine the development of a cosmopolitan neighborhood after World War II that was multicultural and bohemian into something culturally unique. -

Olympic Rowing Regatta Beijing, China 9-17 August

2008 Olympic Rowing Regatta Beijing, China 9-17 August MEDIA GUIDE TABLE OF CONTEnts 1. Introduction 3 2. FISA 5 2.1. What is FISA? 5 2.2. FISA contacts 6 3. Rowing at the Olympics 7 3.1. History 7 3.2. Olympic boat classes 7 3.3. How to Row 9 3.4. A Short Glossary of Rowing Terms 10 3.5. Key Rowing References 11 4. Olympic Rowing Regatta 2008 13 4.1. Olympic Qualified Boats 13 4.2. Olympic Competition Description 14 5. Athletes 16 5.1. Top 10 16 5.2. Olympic Profiles 18 6. Historical Results: Olympic Games 27 6.1. Olympic Games 1900-2004 27 7. Historical Results: World Rowing Championships 38 7.1. World Rowing Championships 2001-2003, 2005-2007 (current Olympic boat classes) 38 8. Historical Results: Rowing World Cup Results 2005-2008 44 8.1. Current Olympic boat classes 44 9. Statistics 54 9.1. Olympic Games 54 9.1.1. All Time NOC Medal Table 54 9.1.2. All Time Olympic Multi Medallists 55 9.1.3. All Time NOC Medal Table per event (current Olympic boat classes only) 58 9.2. World Rowing Championships 63 9.2.1. All Time NF Medal Table 63 9.2.2. All Time NF Medal Table per event 64 9.3. Rowing World Cup 2005-2008 70 9.3.1. Rowing World Cup Medal Tables per year 2005-2008 70 9.3.2. All Time Rowing World Cup Medal Tables per event 2005-2008 (current Olympic boat classes) 72 9.4. -

The Sixties Counterculture and Public Space, 1964--1967

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2003 "Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967 Jill Katherine Silos University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Silos, Jill Katherine, ""Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations. 170. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/170 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

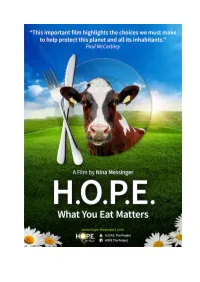

HOPE PRESSKIT.Pdf

H.O.P.E. What You Eat Matters A Film by Nina Messinger Documentary. Austria 2017. Running Time: 92 minutes. Language: English (with subtitles). Frame Rate: 25 fps. Shooting Format: HD. Sound: Dolby Digital 5.1, Stereo 2.0. www.hope-theproject.com H.O.P.E. What You Eat Matters I Press Kit SYNOPSIS (short) Obesity, allergies, diabetes, heart disease, or cancer: More than half of all people living in the industrialized world suffer from chronic diseases. Animals are reared for our consumption under abysmal conditions. Industrial-size livestock breeding facilities contribute to world hunger and the destruction of our natural environment and climate. The documentary H.O.P.E. shows how simply changing what we put on our plates and moving towards a plant-based diet can restore our body´s health and our planet´s balance. It has a clear message: By changing our eating habits, we can change the world! (long) Half of the population in Western society suffers from being overweight. Cardio- vascular diseases, diabetes and cancer are epidemic. Our meat consumption has quintupled over the past 50 years. 65 billion land animals are being slaughtered every year for food consumption. One third of the global grain production is fed to animals for fattening while 1.8 billion people worldwide suffer from hunger and starvation. Can there really be a solution to all these problems? It was the search for an answer to this question that led Austrian author and filmmaker Nina Messinger on a journey through Europe, India and the US to investigate the consequences of our diet and to meet with leading experts in nutrition, medicine, science, and agriculture, as well as with farmers and people who have recovered from severe illnesses by simply changing their eating habits. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 117 230 Relating to Racism, Blacks

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 117 230 ID015 623 TITLE A Selected Annotated Bibliography of .Material Relating to Racism, Blacks, Chicanos, Native Americans and Multi-Ethnicity. Vol-. 2. INSTITUTION Michigan Education Association, East Lansing. iv.'of Minority Affairs. PUB DATE 73 , NOTE 105p.; For volumes 1, 3, and 4; see ED 069 445, VD 015 624 and UD 015 718 respectively EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$5.70 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture; *American Indians; *Annotated Bibliographies; Cultural Background; Cultural Factors; Ethnic'Groups; Ethnic Origins;, Ethnic Status Films; .Filmstrips; Instructional MaterialsC*Mexican Americans; *Negroes; Negro fiistory; Race'Relations; Racial Discrimination; Racial Factors; *Racism; Tape Recordings IDENTIFIERS Third World ABSTRACT The' second in the series, this selected annotated hihliography deals with new and recently discovered materials that address racism, BlackS, Chicanos,'native Americans, and multi - ethnicity. This bibliography is considered to be not all . inclusive but to reflect only on that material which,is considered to be most representative of the realities that relate to the involvemeiA and contributions of Third World groupS in'the development of the United States, and the climate of the times during which such involvement and contributions ocdurred.,Listing of materials usable at the elementary level are increased over those in Volume I. Contents deal with racism, including printed.materials, film, filmstrips, records and tapes; Black materials, including printed matter, films and filmstrips; Latino materials, including printed matter, films and filmstrips; native American materials, k. including printed matter, films and filmstrips; 'and multi-ethnic printed material. A list of Third World publishers is included. , (Author/AM) ********************************************************************* Documents acquired by ERIC include,many .informal Unpublished * materials not available from other sources. -

Suburbanization Historic Context and Survey Methodology

INTRODUCTION The geographical area for this project is Maryland’s 42-mile section of the I-95/I- 495 Capital Beltway. The historic context was developed for applicability in the broad area encompassed within the Beltway. The survey of historic resources was applied to a more limited corridor along I-495, where resources abutting the Beltway ranged from neighborhoods of simple Cape Cods to large-scale Colonial Revival neighborhoods. The process of preparing this Suburbanization Context consisted of: • conducting an initial reconnaissance survey to establish the extant resources in the project area; • developing a history of suburbanization, including a study of community design in the suburbs and building patterns within them; • defining and delineating anticipated suburban property types; • developing a framework for evaluating their significance; • proposing a survey methodology tailored to these property types; • and conducting a survey and National Register evaluation of resources within the limited corridor along I-495. The historic context was planned and executed according to the following goals: • to briefly cover the trends which influenced suburbanization throughout the United States and to illustrate examples which highlight the trends; • to present more detail in statewide trends, which focused on Baltimore as the primary area of earliest and typical suburban growth within the state; • and, to focus at a more detailed level on the local suburbanization development trends in the Washington, D.C. suburbs, particularly the Maryland counties of Montgomery and Prince George’s. Although related to transportation routes such as railroad lines, trolley lines, and highways and freeways, the location and layout of Washington’s suburbs were influenced by the special nature of the Capital city and its dependence on a growing bureaucracy and not the typical urban industrial base. -

Caldwell Esselstyn, M.D

Experts to Follow Caldwell Esselstyn, M.D. ʺDr. Esselstyn is a physician, author and former Olympic rowing champion. He is the author of Prevent and Reverse Heart Disease in which he demonstrates the benefits of a whole- foods, plant-based diet.ʺ To learn more about Dr. Esselstynʹs amazing work visit his website at http://www.dresselstyn.com/ Caldwell B. Esselstyn, Jr., received his B.A. from Yale University and his M.D. from Western Reserve University. In 1956, pulling the No. 6 oar as a member of the victorious United States rowing team, he was awarded a gold medal at the Olympic Games. He was trained as a surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic and at St. Georgeʹs Hospital in London. In 1968, as an Army surgeon in Vietnam, he was awarded the Bronze Star. Dr. Esselstyn has been associated with the Cleveland Clinic since 1968. During that time, he has served as President of the Staff and as a member of the Board of Governors. He chaired the Clinicʹs Breast Cancer Task Force and headed its Section of Thyroid and Parathyroid Surgery. He is a Fellow of the American College of Cardiology. Website: https://www.pbhw.com 1 Email: [email protected] In 1991, Dr. Esselstyn served as President of the American Association of Endocrine Surgeons. That same year he organized the first National Conference on the Elimination of Coronary Artery Disease, which was held in Tucson, Arizona. In 1997, he chaired a follow-up conference, the Summit on Cholesterol and Coronary Disease, which brought together more than 500 physicians and health-care workers in Lake Buena Vista, Florida. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS 16159 Paign Reform to the Committee on House Ad PRIVATE BILLS and RESOLUTIONS H.R

May 17, 1973 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 16159 paign reform to the Committee on House Ad PRIVATE BILLS AND RESOLUTIONS H.R. 7933. A blll for the relief of Luis Os· ministration. valdo Salazar-Cabrera; to the Committee on By Mr. MYERS (for himself, Mr. FREN Under clause 1 of rule XXII, private the Judiciary. ZEL, Mr. MADIGAN, Mr. RINALDO, Mr. bills and resolutions were introduced and RoY, and Mr. TALCOTT) : severally referred as follows: H.J. Res. 560. Joint resolution to authorize By Mr. COUGHLIN: the President to issue a proclamation desig H.R. 7931. A b1ll for the relief of Bruce A. nating the week in November which includes PETITIONS, ETC. Feldman, lieutenant commander, Marine Thanksgiving Day in each year as "National Under clause 1 of rule XXII, Family Week"; to the Committee on the Corps, U.S. Navy Reserve; to the Committee Judiciary. on the Judiciary. 2160. The Speaker presented a petition of By Mr. FUQUA: By Mr. HELSTOSKI: Norman L. Birl, Jr., Rosharon, Tex., relative R. Res. 397. Resolution disapproving Reor H.R. 7932. A bUI for the relief of Mr. and to redress of grievances; to the Committee ganization Plan No. 2; to the Committee on Mrs. Manuel H. Araya; to .the Committee on G~vernment Operations. the Judiciary. on the Judiciary. EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS SENATOR RANDOLPH EXPLAINS IM dents in high schools throughout West "The District Line" . by Bill Gold, which Virginia. In 1968, he said, there were only appeared in the Washington Post on Feb PORTANT ROLE OF POLICE ruary 16, 1973, and in which your latest idea WEST VffiGINIA PROBLEMS ARE three drug arrests made in the State but concerning Charleston's "Buzz-the-Fuzz" LISTED-NATIONAL POLICE WEEK last year there were 434 and he expects program was published in the suggestion FOCUSES ATTENTION 600 this year. -

Benjamin Spock and the Spock Papers at Syracuse University

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries Fall 1987 Benjamin Spock and the Spock Papers at Syracuse University Robert S. Pickett Syracuse University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, and the Child Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Pickett, Robert S. "Benjamin Spock and the Spock Papers at Syracuse University." The Courier 22.2 (1987): 3-22. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXII, NUMBER 2, FALL 1987 SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXII NUMBER TWO FALL 1987 Benjamin Spock and the Spock Papers at Syracuse University By Robert S. Pickett, Professor of Child and 3 Family Studies, Syracuse University Alistair Cooke: A Response to Granville Hicks' I Like America By Kathleen Manwaring, Syracuse University Library 23 "A Citizen of No Mean City": Jermain W. Loguen and the Antislavery Reputation of Syracuse By Milton C. Sernett, Associate Professor 33 of Afro,American Studies, Syracuse University Jan Maria Novotny and His Collection of Books on Economics By Michael Markowski, Syracuse University 57 William Martin Smallwood and the Smallwood Collection in Natural History at the Syracuse University Library By Eileen Snyder, Physics and Geology Librarian, 67 Syracuse University News of the Syracuse University Library and the Library Associates 95 Benjamin Spack and the Spack Papers at Syracuse University BY ROBERT S. -

Managing Your Toddler's Behavior a Famous

Managing Your Toddler’s Behavior A famous parenting expert, Penelope Leach, reminds us that our toddlers are “no longer a baby, but not yet a child.” Toddlers have specific needs for guidance, attention and structure. Here are a few things to keep in mind. 1. Toddlers need a great deal of structure in their lives. We can develop these plans by making sure that we are realistic in our expectations of their attention span, activity level and understanding. Check with our web site section on child development for more specific information. Keep routines in order, as you go through the daily events of dressing, eating, bathing and bedtime. The more a toddler expects these daily activities, the easier it is to make sure they are completed successfully. 2. Toddlers need to feel they have some control or “say” in their lives. Give your toddler just two choices for snack, drinks and clothes. You may say, “Would you like to wear your sweater or your jacket, today?” to avoid a conflict. You know that either choice fine. Offer these choices only when you know the outcome is safe and healthy. 3. Transitioning from one activity to another can be difficult for toddlers. Picking up toys to music or coming to the table “like a butterfly” will make those changes easier to make. Toddlers, like all of us, respond best when they are warned about an activity change approaching. “When this CD is over we need to put the crayons away and get ready for bath time,” may be a way to ease into the next activity. -

December 15, 2008 Perspectives in Theory

December 15, 2008 Perspectives in Theory: Anthology of Theorists affecting the Educational World Editors: Misty M. Bicking, Brian Collins, Laura Fernett, Barbara Taylor, Kathleen Sutton Shepherd University Table Of Contents Abstract_______________________________________________________________________4 Alfred Adler ___________________________________________________________________5 Melissa Bartlett Mary Ainsworth _______________________________________________________________17 Misty Bicking Alois Alzheimer _______________________________________________________________30 Maura Bird Albert Bandura ________________________________________________________________45 Lauren Boyer James A. Banks________________________________________________________________59 Adel D. Broadwater Vladimir Bekhterev_____________________________________________________________72 Thomas Cochrane Benjamin Bloom_______________________________________________________________86 Brian Collins John Bowlby and Attachment Theory ______________________________________________98 Colin Curry Louis Braille: Research_________________________________________________________111 Justin Everhart Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model___________________________________________124 Kristin Ezzell Jerome Bruner________________________________________________________________138 Laura Beth Fernett Noam Chomsky Stubborn Without________________________________________________149 Jamin Gibson Auguste Comte _______________________________________________________________162 Heather Manning