INFORMATION to USERS Xerox University Microfilms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Front Matter

Ingrassia_Gridiron 11/6/15 12:22 PM Page vii © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. Contents List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi INTRODUCTION The Cultural Cornerstone of the Ivory Tower 1 CHAPTER ONE Physical Culture, Discipline, and Higher Education in 1800s America 14 CHAPTER TWO Progressive Era Universities and Football Reform 40 CHAPTER THREE Psychologists: Body, Mind, and the Creation of Discipline 71 CHAPTER FOUR Social Scientists: Making Sport Safe for a Rational Public 93 CHAPTER FIVE Coaches: In the Disciplinary Arena 115 CHAPTER SIX Stadiums: Between Campus and Culture 139 CHAPTER SEVEN Academic Backlash in the Post–World War I Era 171 EPILOGUE A Circus or a Sideshow? 200 Ingrassia_Gridiron 11/6/15 12:22 PM Page viii © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. viii Contents Notes 207 Bibliography 269 Index 305 Ingrassia_Gridiron 11/6/15 12:22 PM Page ix © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. Illustrations 1. Opening ceremony, Leland Stanford Junior University, October 1891 2 2. Walter Camp, captain of the Yale football team, circa 1880 35 3. Grant Field at Georgia Tech, 1920 41 4. Stagg Field at the University of Chicago 43 5. William Rainey Harper built the University of Chicago’s academic reputation and also initiated big-time athletics at the institution 55 6. Army-Navy game at the Polo Grounds in New York, 1916 68 7. G. T. W. Patrick in 1878, before earning his doctorate in philosophy under G. -

Masck V. Sports Illustrated

2:13-cv-10226-GAD-DRG Doc # 1 Filed 01/18/13 Pg 1 of 67 Pg ID 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN ___________________________________ BRIAN MASCK, Plaintiff, File No. v Hon. SPORTS ILLUSTRATED; NISSAN NORTH AMERICA; GETTY IMAGES, INC.; CHAMPIONS PRESS, L.L.C.; DESMOND HOWARD; PHOTO FILE, INC.; FATHEAD, L.L.C.; WAL-MART STORES, INC; WAL-MART.COM USA, L.L.C and AMAZON.COM, INC., Defendant. ___________________________________ Thomas H. Blaske (P26760) John F. Turck IV (P67670) BLASKE & BLASKE, P.L.C. Attorneys for Plaintiff 500 South Main Street Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104 (734) 747-7055 COMPLAINT 2:13-cv-10226-GAD-DRG Doc # 1 Filed 01/18/13 Pg 2 of 67 Pg ID 2 Plaintiff Brian Masck, by and through his attorneys, Blaske & Blaske, P.L.C., for his Complaint says: PARTIES AND JURISDICTION 1. Plaintiff Brian Masck is a resident of Genesee County, Michigan and conducts business within the State of Michigan. 2. Defendant Sports Illustrated (“SI”), is a company owned by Time, Inc., with its principal place of business at 135 West 50th Street, New York, New York 10020, and conducts substantial business within the State of Michigan. 3. SI operates, maintains and controls the web sites Sportsillustrated.CNN.com (“ SI.com ”) and SIKids.com . Sports Illustrated supervises and controls all information contained on its web sites SI.com and SIKids.com . 4. Defendant Nissan North America, Inc. (“Nissan”), with its principal place of business at One Nissan Way, Franklin, Tennessee 37067, conducts substantial business within the State of Michigan. -

Terrapinbasketball

This is TERRAPINBASKETBALL COACHING STAFF 34 • Coaching Staff Coaching Staff • 35 2007-08 MARYLAND Men’s BasketBALL 2002 NCAA CHAMPIONS 2004 ACC CHAMPIONS GARY WILLIAMS HEAD COACh • MARYLANd ‘68 19TH SEASON AT MARYLAND (378-200, .654) 30TH SEASON OVERALL (585-328, .641) Since returning to the College Park campus in 1989, Gary Williams (Maryland ’68) has led his alma mater’s basketball program from a period of troubled times to an era of national prominence. With 12 NCAA Tournament berths in the last 14 seasons, seven Sweet Sixteen appearances, a pair of consecutive Final Four showings, and the 2002 national championship – the first of its kind in Maryland basketball history – Williams and his staff have literally forged what is now more than a decade of dominance in college basketball’s most storied and competitive conference. Now, with 378 victories as Maryland’s head coach, Williams is the school’s Terrapins all-time winningest head coach, eclipsing the mark of former Terp mentor Charles “Lefty” Driesell, who amassed 348 victories in 17 seasons from 1969-70 to 1985-86. The Terrapins have averaged 23.0 wins per year since the 1994-95 season. With 585 career victories in 29 seasons overall, Williams is the seventh-winningest active head coach in NCAA Division I men’s basketball. Williams was heralded as the national and ACC Coach of the Year during the Terps’ 2002 championship run. He is one of just 12 active coaches in America to boast a national title and one of only three in the conference. He has become the third-winningest coach in ACC history after transforming the Maryland program into one of the nation’s most formidable, and building a Baltimore-D.C. -

Dyslexia No Barrier to University of Michigan Grad's 11 Degrees - Ann Arbor News Extra - Mlive.Com

Dyslexia no barrier to University of Michigan grad's 11 degrees - Ann Arbor News Extra - MLive.com • Complete Forecast | Homepage | Site Index | RSS Feeds & Blogs | About Us | Contact Us | Advertise REAL HOME NEWS BUSINESS SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT TRAVEL LIVING FORUMS SHOP JOBS AUTOS CLASSIFIEDS ESTATE MLive.com - Blogs SEARCH: About The Author Dyslexia no barrier to University of Michigan | What's RSS? grad's 11 degrees Ann Arbor News Posted by Kristin Longley | The Flint Journal August 28, 2008 08:08AM Subscribe to Newsletters Categories: M Edition Latest Posts University of Michigan sports teams back in play after a strong 2007-08 season Dyslexia no barrier to University of Michigan grad's 11 degrees CONTESTS Equal opportunity affliction: Contests and University of Michigan Games doctor fights bias in access Click Here to treatment for pain Curry College students join Sudanese refugee's effort FROM OUR to build a well in his native ADVERTISERS • See coupons and village values for local WHOis: Meet some unique businesses. Click Ann Arbor area here! personalities Categories Ann Arbor Art Fairs (RSS) Ann Arbor Schools (RSS) Art fair basics (RSS) Art Fair Diary (RSS) Artists' Stories (RSS) Breaking News (RSS) Photo courtesy of Benjamin Bolger Business News (RSS) Benjamin Bolger on the campus of Harvard University, where he earned his 11th graduate Check this Out (RSS) degree. Featured Stories (RSS) Job Market (RSS) M Edition (RSS) RELATED: Complete M Edition Outlook 2007 (RSS) Outlook 2008 (RSS) Readers' Choice (RSS) Benjamin Bolger might very well be the most academically accomplished Shakey Jake (RSS) elementary-school dropout in recent history. -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

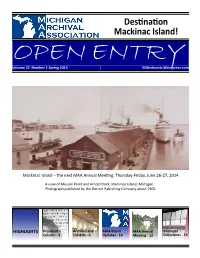

Destination Mackinac Island! OPEN ENTRY Volume 42 Number 1 Spring 2014 Miarchivists.Wordpress.Com

Destination Mackinac Island! OPEN ENTRY Volume 42 Number 1 Spring 2014 MiArchivists.Wordpress.com Mackinac Island – the next MAA Annual Meeting, Thursday-Friday, June 26-27, 2014 A view of Mission Point and Arnold Dock, Mackinac Island, Michigan. Photograph published by the Detroit Publishing Company about 1905. HIGHLIGHTS President’s Archives and MAA Board MAA Annual Michigan Column - 3 Exhibits - 6 Updates - 10 Meeting - 12 Collections - 14 OPEN ENTRY is the newsletter of the Michigan Archival Association Editor, Rebecca Bizonet Production Editor, Cynthia Read Miller All submissions should be directed to the Editors: [email protected] By the deadlines: • September 5 - Fall 2014 issue • January 31 - Spring 2015 issue MAA Board Members Spring 2014 Officers Members-at-Large Kristen Chinery Rebecca Bizonet (2011-2014) & Open Entry, Editor President (2012-2014) Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University 20900 Oakwood Boulvard, Dearborn, MI 48124-5029 5401 Cass Avenue, Detroit, MI 48202 (313) 982-6100 ext. 2284 [email protected] (313) 577-8377 [email protected] Karen Jania (2011-2014) Melinda McMartin Isler Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan Vice President/President-elect (2012-2014) & MAA 1150 Beal Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2113 Online, Editor (734) 764-3482 [email protected] University Archives, Ferris State University, Alumni 101 410 Oak St., Big Rapids, MI 49307 Elizabeth Skene (2012-2015) (231) 591-3731 [email protected] Arab American National Museum 13624 Michigan Avenue, Dearborn, MI 48126 Cheney J. Schopieray (313) 624-0229 [email protected] secretary (2012-2014) William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan Carol Vandenberg (2012-2015) 909 S. -

White House Special Files Box 59 Folder 1

Richard Nixon Presidential Library White House Special Files Collection Folder List Box Number Folder Number Document Date Document Type Document Description 59 1 10/23/1962 Letter Contact mailing letter to Trojans from Francis Tappaan, Chairman of the Trojan Alumni for Nixon Committee. 1 pg. 5 duplicates not scanned. 59 1 10/29/1962 Memo Memo from Sammy to Rose about mailing. 1 pg. 59 1 1962 Letter Contact mailing to the members of the CA Teacher's Association from Richard Nixon. Includes envelope and contact card. 4 pgs. Attached to previous. 2 duplicate packets not scanned. 59 1 1962 Letter Contact mailing to Lawyers from Lawyers for Nixon Committee. 2 pgs. Envelope, contact card, and duplicate packet not scanned. 59 1 10/29/1962 Memo Memo from Sammy to Rose about mailing. 1 pg. 59 1 1962 Letter Contact mailing to Sportsmen from Bob Reynolds, Chairman of the Sports Advisory Committee. 1 pg. Envelope and contact card not scanned. Only cover scanned of Nixon brochure. Attached to previous. 2 duplicate packets not scanned. Tuesday, July 31, 2007 Page 1 of 4 Box Number Folder Number Document Date Document Type Document Description 59 1 1962 Letter Contact mailing to Doctor from Dr. Charles Lippincott. 1 pg. Duplicate not scanned. 59 1 1962 Letter Contact mailing to Colleague from Park Ewart, Co-Chairman of the Scholars for Nixon Committee. 1 pg. Duplicate not scanned. 59 1 1962 Memo Memo from Jennifer Paul to Dorothy Wright. 1 pg. 59 1 1962 Letter Contact mailing to Businessman from William Logan, Chairman of the California Small Business Committee for Nixon. -

Grizzly Football Game Day Program, October 12, 1957 University of Montana—Missoula

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Grizzly Football Game Day Programs, 1914-2012 University of Montana Publications 10-12-1957 Grizzly Football Game Day Program, October 12, 1957 University of Montana—Missoula. Athletics Department Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/grizzlyfootball_programs_asc Recommended Citation University of Montana—Missoula. Athletics Department, "Grizzly Football Game Day Program, October 12, 1957" (1957). Grizzly Football Game Day Programs, 1914-2012. 39. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/grizzlyfootball_programs_asc/39 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Montana Publications at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Grizzly Football Game Day Programs, 1914-2012 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OFFICIAL SOUVENIR PMGRAM MAGAZINE 35 CENTS HOM Lucky Program N ? 25411 SATURDAY, OCT. 12, 1957, 1:30 p.m., DORNB Homecoming . 0 T T BETH BURBANK =• ... Synadelphic w a s 1" fP^ c a s l a SUE MARX Sigma KaPP Delta Gamma MISSOULA AUTOMOBILE DEALERS ASSOCIATION P. O. Box 1469 Telephone 9-1762 OLNEY MOTORS AREHART BUICK CO. GARDEN CITY MOTORS TURMELL MOTOR CO. BAKKE MOTOR CO. KRAABEL CHEVROLET CO MISSOULA HUDSON CO. H. O. BELL CO. BUD LAKE EDSEL SALES CO. WAKLEY MOTORS GRAEHL MOTOR SERVICE Jhj2 Spsudaiuh 'fyhidi/wn^uidsi TABLE OF CONTENTS Homecoming Royalty J. D. COLEMAN— Editor 2, 39 Today's game, a triple report 4, 5, 6 ROBERT McGIHON—Sales Manager M.S.U. -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

Cortland Football Quick Facts

CORTLAND FOOTBALL 2019 TEam Guide Red Dragons Empire 8 Runner-up, Postseason Qualifier in 2018 Cortland placed second in the Empire 8 with a 5-2 league record and finished 7-3 overall during the 2018 season. The Red Dragons’ three losses were by only a combined 13 points. Cortland earned its 23rd postseason berth as the Empire 8’s qualifier for the New York Bowl, but was denied a chance to successfully defend its crown as the game was canceled due to the lack of a declared opponent from the Liberty League. Cortland set school records for scoring average (39.3 points per game) and passing yardage average (295.9 yards per game), while quarterback Brett Segala set a school regular-season mark with 2,671 passing yards. Jake Smith earned D3football.com All-America and All-East honors on special teams (two blocked kicks) and Cole Burgess was an All-East kick returner (28.7 yards per kickoff return, two touchdowns). Nick Mongelli was named the Empire 8 Special Teams Player of the Year after making 8-of-9 field goals along with a school regular-season record 47 PAT kicks. Smith (at wide receiver), Mongelli, Burgess and defensive lineman Dan Appley were all first team All-Empire 8 honorees. Segala, offensive linemen David Aaronson and Russell Howard, running back Johnnie Akins, defensive backs Isaac Hicks III and Max Jean, linebacker Kyle Richard, and Alex David Aaronson earned second team All-Empire 8 honors as a Wasserman (as an all-purpose selection) were named to the junior in 2018. -

The University of Michigan

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Michigan Legal Studies Series Law School History and Publications 1969 The niU versity of Michigan: Its Legal Profile William B. Cudlip Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/michigan_legal_studies Part of the Education Law Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Cudlip, William B. The nivU ersity of Michigan: Its Legal Profile. Ann Arbor: Univ. of Michigan, 1969. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School History and Publications at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Legal Studies Series by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN: ITS LEGAL PROFILE THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN: ITS LEGAL PROFILE by William B. Cudlip, J.D. Published under the auspices of The University of Michigan Law School (which, however, assumes no responsibility for the views expressed) with the aid of funds derived from a gift to The University of Michigan by the Barbour-Woodward Fund. Copyright© by The University of Michigan, 1969 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I suppose that lawyers are always curious about the legal history of any institution with which they are affiliated. As the University of Michigan approached its One Hundred Fiftieth year, my deep interest was heightened as I wondered about the legal structure and involvements of this durable edifice over that long period of time. This compendium is the result and I acknowledge the help that I have had. -

First Team All-Big Ten Boilermakers

The Final SeaSon aT lamberT Field Coaching Staff 2011 boilermaker baSeball • a Farewell To lamberT Field 1 2011 Purdue boilermakerS baSeball Program Information QUICK FACTS BASEBALL CoACHInG STAFF InFormATIon Name of University .............................................................. Purdue University Head Coach ............................................................................. Doug Schreiber Location ............................................................................West Lafayette, Ind. Alma Mater........................................................................................... Purdue Founded ...................................................................................................1869 Record at Purdue (Years) ............................................................. 343-328 (12) Enrollment .............................................................................................39,697 Career Record ..........................................................................................Same Nickname ....................................................................................Boilermakers Schreiber Office Phone ............................................................ (765) 494-3998 School Colors .........................................................................Old Gold & Black Screiber E-Mail ......................................................... [email protected] Baseball Office Phone .............................................................. (765) 494-3217