Adam to Joshua: Tracing a Paragenealogy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Konkel-OT-3XJ3-Joshua-F19.Pdf

Syllabus McMaster Divinity College Fall 2019 Course Designation OT 3XJ3 Joshua Specializations Biblical Studies Pastoral Studies Those students not yet committed to a program with a selected specialization will need to register the course in one of the two specializations. Check the assignment requirements to decide which of the specializations you may prefer. Course Schedule Tuesday 6:30 p.m. – 8:20 p.m. Classes begin Tuesday September 10. No class on Tuesday Oct. 15 (intensive hybrid week) Final class is Tuesday Dec. 10 Instructor August H. Konkel, Professor of Old Testament (Ph.D.) [email protected]; 905 525 9140 x 23505 https://mcmasterdivinity.ca/faculty-and-administration/august-h-konkel/ Joshua Course Description The book of Joshua is challenging in various ways. It is difficult to bring coherence to apparently contradictory assertions: all the land was conquered yet much land remains to be taken; all the Canaanites are to be destroyed yet Israel lives amongst the Canaanites. Joshua is a challenging book theologically, as the promise of redemption comes about through war and conflict. The goal of this course is to provide a guide in understanding the book of Joshua in its literary intent and its theological message in dealing with the concepts of judgment and redemption. It is to provide guidance for living in a world that is torn by strife. Course Objectives Knowing Content and structure of the versions of Joshua (Masoretic, Greek, and Qumran) Questions of textual history and the process of composition Relationship of Joshua -

Notes on Zechariah 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Zechariah 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE AND WRITER The title of this book comes from its traditional writer, as is true of all the prophetical books of the Old Testament. The name "Zechariah" (lit. "Yahweh Remembers") was a common one among the Israelites, which identified at least 27 different individuals in the Old Testament, perhaps 30.1 It was an appropriate name for the writer of this book, because it explains that Yahweh remembers His chosen people, and His promises, and will be faithful to them. This Zechariah was the son of Berechiah, the son of Iddo (1:1, 7; cf. Ezra 5:1; 6:14; Neh. 12:4, 16). Zechariah, like Jeremiah and Ezekiel, was both a prophet and a priest. He was obviously familiar with priestly things (cf. ch. 3; 6:9-15; 9:8, 15; 14:16, 20, 21). Since he was a young man (Heb. na'ar) when he began prophesying (2:4), he was probably born in Babylonian captivity and returned to Palestine very early in life, in 536 B.C. with Zerubbabel and Joshua. Zechariah apparently survived Joshua, the high priest, since he became the head of his own division of priests in the days of Joiakim, the son of Joshua (Neh. 12:12, 16). Zechariah became a leading priest in the restoration community succeeding his grandfather (or ancestor), Iddo, who also returned from captivity in 536 B.C., as the leader of his priestly family (Neh. 12:4, 16). Zechariah's father, Berechiah (1:1, 7), evidently never became prominent. -

2021/5782 ROSH HASHANAH 1 Tishrei 5782

2021/5782 ROSH HASHANAH 1 Tishrei 5782 Erev Rosh Hashanah, Monday, September 6, 2021 Rosh Hashanah Tuesday, September 7, 2021 The Children’s Shofars were generously underwritten by Nancy & Robert Levinthal The bimah flowers for Rosh Hashanah are lovingly given in Memory of Sally Fuchs by her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren All services available online at www.beth-israel.org Honored Rosh Hashanah Congregants Joan and Stanford Alexander Martha Barvin Jonathan Finger Dr. Jennifer Guss Karen Harberg Ronnie Ladin Max and Rochelle Levit Rosalyn Margolis Dr. Ed Septimus Scott Cantor and Lisa Stone Erev Rosh Hashanah, Monday, September 6 1 Tishrei 5782 6:30 p.m. Erev Rosh Hashanah Service Rosh Hashanah Prayer Book or www.ccarnet.org/publications/hhd/# Rabbi David A. Lyon Rabbi Adrienne P. Scott Rabbi Aaron K. Sataloff Cantor Richard Cohn New Year’s Greetings Roslyn Fuchs Haikin, President, Board of Trustees Blessing of Festival Lights Lisa Lyon and Leslie Margolis, Trustee Sermon Rabbi David A. Lyon “My Extra Life” Bimah Guests Roslyn Fuchs Haikin, President Leslie Margolis, Trustee Ed Wolff, Trustee Rosh Hashanah, Tuesday, September 7 1 Tishrei 5782 9:15 a.m. Online Children's Service Zoom Link zoom.us/j/96449874537? pwd=cXluR25KZDVFdjJaUzh3M0Nyd0hndz09 Meeting ID: 964 4987 4537 Passcode: 836363 Rosh Hashanah, Tuesday, September 7 1 Tishrei 5782 10:30 a.m. Morning Service Rosh Hashanah Prayer Book or online www.ccarnet.org/publications/hhd/# Rabbi David A. Lyon Rabbi Adrienne P. Scott Rabbi Aaron K. Sataloff Cantor Richard Cohn Shofar Service, p. 200, 267, 282 David M. Scott, R.J.E. -

Rahab in the Book of Joshua and Other Texts of the Bible

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 19, Issue 3, Ver. II (Mar. 2014), PP 19-29 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Rahab in the Book of Joshua and other Texts of the Bible Obiorah Mary Jerome Department of Religion and Cultural Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria Abstract: Christian Sacred Scripture embodies some puzzling episodes which human minds can grasp only through similar faith that inspired its writers. The story of Rahah, presented as a prostitute in the Book of Joshua, provides such enigma. This woman rose from being a prostitute to a heroine for she was numbered among the Ancestresses of Jesus Christ. Her singular manifestation of faith in God and subsequent interpretations of this in the two parts of the Christian Bible are the focus of this paper. It is discovered that God’s ways are not our ways, for the Creator can choose anyone and at any time to accomplish his design. Keywords: Faith in God, Jericho, The Book of Joshua, Rahab, Spies I. INTRODUCTION At its face value the New Testament perspectives and interpretations of Rahab‟s story and personality as presented in the Book of Joshua appear surprising or even misapprehension of reality. She was a marginal woman with unusual character. In fact, the Hebrew version of Joshua 2 describes her as ‟iššāh zônāh – a professional secular prostitute distinct from qědēšāh – “sacred prostitute”; the latter would have been more respectful. It is instructive to observe that the texts of the New Testament and early Christian writers that appropriated the attitude of this woman towards the Israelite spies in projecting their theological thrusts preserve her Old Testament designation or identity when they still describe her as hē pornē “prostitute”. -

Jesus, Elisha, and Moses: a Study in Typology

Running head: JESUS, ELISHA, AND MOSES 1 Jesus, Elisha, and Moses: A Study in Typology Jeremy Tetreau A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2018 JESUS, ELISHA, AND MOSES 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Donald Fowler, Th.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Harvey Hartman, Th.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Mark Harris, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Cindy Goodrich, Ed.D., M.S.N., R.N., C.N.E. Assistant Honors Director ______________________________ Date JESUS, ELISHA, AND MOSES 3 Abstract Because the Evangelists wrote with the intention of communicating specific, theological truths to their readers, the details they include in their gospels are important. Further, one way the story of the Bible unfolds and is theologically interpreted is through the use of repetition and typology. A number of the miracle accounts of Elisha are analogous to Jesus’ own miracles as recorded in the gospels. Because of this, it is likely that the Evangelists are inviting readers to understand Jesus in light of Old Testament prophets and events, specifically as the appearance of a Prophet-like-Moses. A Jesus-Elisha typology, then, must be understood as only one strand of this more intricate prophetic typology. JESUS, ELISHA, AND MOSES 4 Jesus, Elisha, and Moses Introduction The writers of the four canonical gospels were not mere biographers; they were theologians. They were propagandists in the best possible way. They were the Evangelists, tasked with the sacred privilege of faithfully compiling eyewitness testimony and portraying Jesus “as these eyewitnesses portrayed him,” giving that testimony “a permanent literary vehicle.”1 Luke informs us that his gospel was written “so that you may know the exact truth about the things you [Theophilus] have been taught” (Lk. -

Elijah & Elisha

1 & 2 Kings Elijah & Elisha • In the midst of this history of king after king leading the people away from God, we find two prophets who demonstrate God’s grace and covenant faithfulness despite the people’s sin. • The narrative space and the narrative placement of these two prophets highlight their importance to the narrative as a whole. • The account of these two prophets, Elijah and Elisha, in 1 Kings 17 - 2 Kings 13, is the center of the book of Kings, comprising roughly 40% of the narrative. • One of the primary ways that the two prophets remind the people who God is and what it means to live before him is through the presence and the power of the Holy Spirit in their lives. • This emphasis on the Holy Spirit in the life and ministry of Elisha helps us to understand his purpose in Kings and the whole of the biblical canon, and gives us more insight into the things concerning Jesus in all the Scriptures (Luke 24:27). • In the context of Kings, as so many in Israel have rejected God and his covenant, Elisha serves not only as a prophet calling the people to covenant faithfulness, but as the Spirit-empowered man of God who walks with God, represents God, and demonstrates the way to covenant faithfulness. • As the Spirit-empowered man of God leading the people to covenant faithfulness, however, Elisha serves as more than an example of living before God under the Old Covenant; he also serves as a preview of what it will mean to walk with God in the New Covenant in Jesus Christ, which is ultimately how God’s people will know him and what it means to live for him. -

Medieval Shiloh—Continuity and Renewal

religions Article Medieval Shiloh—Continuity and Renewal Amichay Shcwartz 1,2,* and Abraham Ofir Shemesh 1 1 The Israel Heritage Department, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Ariel University, Kiryat Hamada Ariel 40700, Israel; [email protected] 2 The Department of Middle Eastern Studies, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan 5290002, Israel * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 25 August 2020; Accepted: 22 September 2020; Published: 27 September 2020 Abstract: The present paper deals with the development of cult in Shiloh during the Middle Ages. After the Byzantine period, when Shiloh was an important Christian cult place, it disappeared from the written sources and started to be identified with Nebi Samwil. In the 12th century Shiloh reappeared in the travelogues of Muslims, and shortly thereafter, in ones by Jews. Although most of the traditions had to do with the Tabernacle, some traditions started to identify Shiloh with the tomb of Eli and his family. The present study looks at the relationship between the practice of ziyara (“visit” in Arabic), which was characterized by the veneration of tombs, and the cult in Shiloh. The paper also surveys archeological finds in Shiloh that attest to a medieval cult and compares them with the written sources. In addition, it presents testimonies by Christians about Jewish cultic practices, along with testimonies about the cult place shared by Muslims and Jews in Shiloh. Examination of the medieval cult in Shiloh provides a broader perspective on an uninstitutionalized regional cult. Keywords: Shiloh; medieval period; Muslim archeology; travelers 1. Introduction Maintaining the continuous sanctity of a site over historical periods, and even between different faiths, is a well-known phenomenon: It is a well-known phenomenon that places of pilgrimage maintain their sacred status even after shifts in the owners’ faith (Limor 1998, p. -

Job Bible Study Notes and Comments

Commentary on the Book of Job Bible Study Notes and Comments by David E. Pratte Available in print at www.gospelway.com/sales Commentary on the Book of Job: Bible Study Notes and Comments © Copyright David E. Pratte, 2010, 2014 Minor revisions 2016 All rights reserved ISBN-13: 978-1495909535 ISBN-10: 1495909530 Note carefully: No teaching in any of our materials is intended or should ever be construed to justify or to in any way incite or encourage personal vengeance or physical violence against any person. Front page photo Statue with artist’s conception of Job Photo credit: Jörg Syrlin the Younger distributed under GNU free documentation license, via Wikimedia Commons Other Acknowledgements Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are generally from the New King James Version (NKJV), copyright 1982, 1988 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked (NASB) are from Holy Bible, New American Standard La Habra, CA: The Lockman Foundation, 1995. Scripture quotations marked (ESV) are from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version, copyright ©2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked (MLV) are from Modern Literal Version of The New Testament, Copyright 1999 by G. Allen Walker. Scripture quotations marked (RSV) are from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1952 by the Division of Christian Education, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Scripture quotations marked (NIV) are from the New International Version of the Holy Bible, copyright 1978 by Zondervan Bible publishers, Grand Rapids, Michigan. -

4. Son of Jehozadak 5. Son of Eliezer Joshua (Book and Person)

757 Joshua (Book and Person) 758 4. Son of Jehozadak from him (in contrast to Moses). He is an isolated Joshua, the son of Jehozadak, is mentioned in Hag- figure, a “one-task hero.” His tomb is extra-territo- gai, Zechariah, and 1 Chronicles (see “Joshua [Son rial in the lot of Ephraim (Josh 19 : 50), even if he of Jehozadak], the High Priest”). He is also men- has been “constructed” to represent this tribe (Num tioned in Ezra 3 as Jeshua (see “Jeshua 6. Son of Je- 14 : 8). This information indicates that Joshua, as hozadak”). opposed to Abraham, Jacob, and Moses, was a Ellen White scribal creation, rather than a figure of tribal tradi- tion. Veneration for the tombs of the prophets be- 5. Son of Eliezer gan in Israel no later than the 4th century BCE (2 Kgs 13 : 20–21, cf. also 1 Kgs 13 : 30–32; 2 Kgs According to Luke 3 : 28–29, one of the ancestors of 23 : 16–18), i.e., around the time the first “book of Jesus was Joshua, son of Eliezer and father of Er. Joshua” ends. The literary history of Joshua began Nothing else is known about him. in the second half of the 7th century BCE, provid- Dale C. Allison, Jr. ing ample time for his tomb to “materialize” by the time the book was concluded. Martin Noth’s hy- Joshua (Book and Person) pothesis, according to which Joshua’s tomb is the (only) attestation of a “historical Joshua,” should I. Hebrew Bible/Old Testament therefore be abandoned. -

United States District Court District of Maryland

Case 8:15-cv-03875-TDC Document 135 Filed 05/21/20 Page 1 of 11 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF MARYLAND JOSHUA MOSES, Plaintiff, v. MOHAMED S. MOUBAREK, CHRISTOPHER TODD, LISA HALL, Civil Action No. TDC-15-3875 PHIL BOCH, KRISTINE SWICK, MICHELE VOORHEES and THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Defendants. MEMORANDUM OPINION Plaintiff Joshua Moses, formerly an inmate at the Federal Correctional Institution in Cumberland, Maryland (“FCI-Cumberland”), has filed suit against the United States of America and several FCI-Cumberland medical providers, Defendants Dr. Mohamed S. Moubarek, Christopher Todd, Lisa Hall, Phil Boch, Kristine Swick, and Michelle Voorhees (collectively “the Medical Defendants”). Presently pending before the Court is Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss the Second Amended Complaint. The Court has reviewed the operative pleading and the briefs and finds no hearing necessary. D. Md. Local R. 105.6. For the reasons set forth below, Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss will be DENIED. BACKGROUND Much of the factual background of this case is set forth in the Court’s September 9, 2016 Memorandum Opinion denying the Motion for a Preliminary Injunction, Moses v. Stewart (“Moses I”), No. TDC-15-3875, 2016 WL 4761929, at *1-5 (D. Md. Sept. 9, 2016), and the Court’s Case 8:15-cv-03875-TDC Document 135 Filed 05/21/20 Page 2 of 11 September 26, 2017 Memorandum Opinion denying Defendants’ first Motion to Dismiss, or in the Alternative, for Summary Judgment, Moses v. Stewart (“Moses II”), No. TDC-15-3875, 2017 WL 4326008, at *1-4. The Court incorporates by reference that factual background, summarizes only those portions of that history most relevant to the pending Motion, and describes in detail only the new facts alleged in the Second Amended Complaint. -

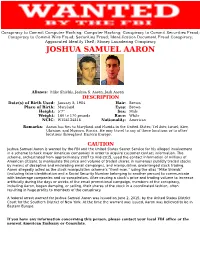

Joshua Samuel Aaron

Conspiracy to Commit Computer Hacking; Computer Hacking; Conspiracy to Commit Securities Fraud; Conspiracy to Commit Wire Fraud; Securities Fraud; Identification Document Fraud Conspiracy; Aggravated Identity Theft; Money Laundering Conspiracy JOSHUA SAMUEL AARON Aliases: Mike Shields, Joshua S. Aaron, Josh Aaron DESCRIPTION Date(s) of Birth Used: January 8, 1984 Hair: Brown Place of Birth: Maryland Eyes: Brown Height: 5'7" Sex: Male Weight: 160 to 170 pounds Race: White NCIC: W154134818 Nationality: American Remarks: Aaron has ties to Maryland and Florida in the United States; Tel Aviv, Israel; Kiev, Ukraine; and Moscow, Russia. He may travel to any of these locations or to other locations throughout Eastern Europe. CAUTION Joshua Samuel Aaron is wanted by the FBI and the United States Secret Service for his alleged involvement in a scheme to hack major American companies in order to acquire customer contact information. The scheme, orchestrated from approximately 2007 to mid-2015, used the contact information of millions of American citizens to manipulate the price and volume of traded shares in numerous publicly traded stocks by means of deceptive and misleading email campaigns, and manipulative, prearranged stock trading. Aaron allegedly acted as the stock manipulation scheme’s “front-man,” using the alias “Mike Shields” (including false identification and a Social Security Number belonging to another person) to communicate with brokerage companies and co-conspirators. After causing a stock’s price and trading volume to increase artificially during the days or weeks of the email promotional campaign, members of the conspiracy, including Aaron, began dumping, or selling, their shares of the stock in a coordinated fashion, often resulting in huge profits to members of the conspiracy. -

Understanding Micah's Lament for Judah

7 Understanding Micah’s Lament for Judah (Micah 1:10–16) through Text, Archaeology, and Geography George A. Pierce George A. Pierce is an assistant professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University. artin Luther once stated that the prophets “have a queer way Mof talking, like people who, instead of proceeding in an orderly manner, ramble off from one thing to the next, so that you cannot make head or tail of them or see what they are getting at.”1 This is especially true for Micah 1:10–16, in which Micah’s prophetic lament employs several forms of Hebrew wordplay, termed paronomasia, a literary device found throughout the Old Testament that employs the phonology and meaning of words to give added emphasis to a persuasive argument.2 The prophets have the highest occurrences of this rhetorical device when compared to other genres in the Hebrew Bible, such as law, history, or wisdom literature, and in this passage, the wordplay of the prophet’s lament draws on the names of towns or villages in the rural Judean countryside to illustrate impending judgment and destruction. This chapter seeks to explicate the word- play Micah used in lamenting the cities around him by surveying the 162 George A. Pierce geographical and historical settings behind Micah’s oracle as related within biblical and Assyrian texts, by considering archaeological and geographic information, and by examining the mechanics of the text. Thus text, archaeology, and geography should not only give perspec- tive to Micah’s lament but also inform the potential application of the text in addition to the larger theological message of Micah for the modern reader.