UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Digital Distribution

HOW DIGITAL DISTRIBUTION AND EVALUATION IS IMPACTING PUBLIC SERVICE ADVERTISING Aggressive Promotion Yields Significant Results By Bill Goodwill & James Baumann It is no surprise to see that digital distribution of all media products is fast becoming the de facto standard for distribution of media content, particularly for shorter videos such as PSA messages. First let’s define the terms. Digital distribution (also called digital content delivery, online distribution, or electronic distribution), is the delivery of media content online, thus bypassing physical distribution methods, such as video tapes, CDs and DVDs. In additional to saving money on tapes and disks, digital distribution eliminates the need to print collateral materials such as storyboards, newsletters, bounce-back cards, etc. Finally, it provides the opportunity to preview messages online, and offers media high- quality files for download. The “Pull” Distribution Model In the pre-digital world, the media was spoiled because they had all the PSA messages they could ever use delivered right to their desktop, along with promotional materials explaining the importance of the campaigns. Today, the standard way for stations to get PSAs in the digital world is to go to a site created by the digital distribution company and download them from the “cloud.” Using a dashboard that has been created for PSAs, the media can preview the spots and download both the PSAs, as well as digital collateral materials such as storyboards, a newsletter and traffic instructions. This schematic shows the overall process flow for digital distribution. To provide more control over digital distribution, Goodwill Communications has its own digital distribution download site called PSA Digital™, and to see how we handle both TV and radio digital files, go to: http://www.goodwillcommunications.com/PSADigital.aspx. -

The Effects of Digital Music Distribution" (2012)

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 4-5-2012 The ffecE ts of Digital Music Distribution Rama A. Dechsakda [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp The er search paper was a study of how digital music distribution has affected the music industry by researching different views and aspects. I believe this topic was vital to research because it give us insight on were the music industry is headed in the future. Two main research questions proposed were; “How is digital music distribution affecting the music industry?” and “In what way does the piracy industry affect the digital music industry?” The methodology used for this research was performing case studies, researching prospective and retrospective data, and analyzing sales figures and graphs. Case studies were performed on one independent artist and two major artists whom changed the digital music industry in different ways. Another pair of case studies were performed on an independent label and a major label on how changes of the digital music industry effected their business model and how piracy effected those new business models as well. I analyzed sales figures and graphs of digital music sales and physical sales to show the differences in the formats. I researched prospective data on how consumers adjusted to the digital music advancements and how piracy industry has affected them. Last I concluded all the data found during this research to show that digital music distribution is growing and could possibly be the dominant format for obtaining music, and the battle with piracy will be an ongoing process that will be hard to end anytime soon. -

Curating Precarity. Swedish Queer Film Festivals As Micro-Activism

Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis Uppsala Studies in Media and Communication 16 Curating Precarity Swedish Queer Film Festivals as Micro-Activism SIDDHARTH CHADHA Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Lecture Hall 2, Ekonomikum, Kyrkogårdsgatan 10, Uppsala, Thursday, 15 April 2021 at 13:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Dr. Marijke de Valck (Department of Media and Culture, Utrecht University). Abstract Chadha, S. 2021. Curating Precarity. Swedish Queer Film Festivals as Micro-Activism. Uppsala Studies in Media and Communication 16. 189 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-513-1145-6. This research is based on ethnographic fieldwork conducted at Malmö Queer Film Festival and Cinema Queer Film Festival in Stockholm, between 2017-2019. It explores the relevance of queer film festivals in the lives of LGBTQIA+ persons living in Sweden, and reveals that these festivals are not simply cultural events where films about gender and sexuality are screened, but places through which the political lives of LGBTQIA+ persons become intelligible. The queer film festivals perform highly contextualized and diverse sets of practices to shape the LGBTQIA+ discourse in their particular settings. This thesis focuses on salient features of this engagement: how the queer film festivals define and articulate “queer”, their engagement with space to curate “queerness”, the role of failure and contingency in shaping the queer film festivals as sites of democratic contestations, the performance of inclusivity in the queer film festival organization, and the significance of these events in the lives of the people who work or volunteer at these festivals. -

Fall River Author, 13, Wins Writing Contest for Full-Length Novel

× Herald News ___ GateHouse Media,LLC VIEW FREE - In Google Play (MARKET://DETAILS?ID=COM.GATEHOUSEMEDIA.ID3108) Fall River author, 13, wins writing contest for full-length novel By Deborah Allard Herald News Staff Reporter Posted Aug 14, 2019 at 4:48 PM FALL RIVER — When a shadow separates from its human, its owner must embark on a quest to another dimension to find it – or there will be darkness. That is the premise of fantasy novel “Dark Shadows” by first-time author and writing contest winner Anya Costello, age 13. “It’s kind of crazy,” Costello said. “I’m definitely excited for it.” Costello submitted her 227-page novel about the errant shadow to MacKenzie Press and its Stone Soup literary magazine Secret Kids writing contest last winter. She not only won the contest and $1,000, but her novel will be the first book published under MacKenzie Press’ new imprint “For Teens, Written by Teens,” to debut in the fall of 2020. “I feel like once it’s published, it’ll feel a lot more real,” Costello said. Her mother, Audra Costello, said it was “surreal” to think that her teen daughter has written a full-length novel that will be published. Then again, Costello has been writing and “creating a world of imaginary characters” since she was 4 years old, her mother said. “She started reading young and was always interested in books.” Costello said she has filled lots of notebooks with short stories. “Dark Shadows” will be a trilogy. “I like writing different worlds and different mythologies,” she said. -

Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960S and Early 1970S

TV/Series 12 | 2017 Littérature et séries télévisées/Literature and TV series Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s Dennis Tredy Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/2200 DOI: 10.4000/tvseries.2200 ISSN: 2266-0909 Publisher GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Electronic reference Dennis Tredy, « Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s », TV/Series [Online], 12 | 2017, Online since 20 September 2017, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/2200 ; DOI : 10.4000/tvseries.2200 This text was automatically generated on 1 May 2019. TV/Series est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series o... 1 Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s Dennis Tredy 1 In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, in a somewhat failed attempt to wrestle some high ratings away from the network leader CBS, ABC would produce a spate of supernatural sitcoms, soap operas and investigative dramas, adapting and borrowing heavily from major works of Gothic literature of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. The trend began in 1964, when ABC produced the sitcom The Addams Family (1964-66), based on works of cartoonist Charles Addams, and CBS countered with its own The Munsters (CBS, 1964-66) –both satirical inversions of the American ideal sitcom family in which various monsters and freaks from Gothic literature and classic horror films form a family of misfits that somehow thrive in middle-class, suburban America. -

Roxy Music Viva! the Live Roxy Music Album Mp3, Flac, Wma

Roxy Music Viva! The Live Roxy Music Album mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Viva! The Live Roxy Music Album Country: US Released: 1976 Style: Glam, Art Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1628 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1319 mb WMA version RAR size: 1978 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 630 Other Formats: AA APE MIDI VOC MP1 ASF AIFF Tracklist Hide Credits Out Of The Blue A1 4:40 Written-By – Manzanera* A2 Pyjamarama 3:27 A3 The Bogus Man 7:05 A4 Chance Meeting 3:01 A5 Both Ends Burning 4:54 B1 If There Is Something 10:29 B2 In Every Dream Home A Heartache 8:10 B3 Do The Strand 3:55 Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Atlantic Recording Corporation Pressed By – Presswell Produced For – E.G. Records Ltd. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Atlantic Recording Corporation Copyright (c) – Atlantic Recording Corporation Published By – E.G. Music Published By – TRO-Total Published By – TRO-Cheshire Recorded At – Apollo Theatre, Glasgow Recorded At – Newcastle City Hall Recorded At – Empire Pool, Wembley Mixed At – Air Studios Mastered At – Atlantic Studios Credits Backing Vocals – The Sirens Bass – John Gustafson, John Wetton, Rick Wills, Sal Maida Crew – Chris Adamson, Mick Rossi Drums – Paul Thompson Engineer – Bill Price, Chris Michie , Frank Owen, John Punter, Rhett Davies Engineer [Mix] – Steve Nye Engineer [Mix] [Assistant] – Jon Walls Guitar – Phil Manzanera Mastered By – GP* Producer – Chris Thomas Saxophone, Oboe – Andrew Mackay* Strings, Synthesizer, Keyboards – Edwin Jobson* Voice, Keyboards – Bryan Ferry Written-By – Ferry* Notes Presswell (PR matrix code on label) Recorded Live at the Apollo, Glasgow, November 1973 - The City Hall, Newcastle, November 1974 and The Empire Pool, Wembley, October 1975. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

REBELS on POINTE Featuring LES BALLETS TROCKADERO DE MONTE CARLO

REBELS ON POINTE Featuring LES BALLETS TROCKADERO DE MONTE CARLO A film by Bobbi Jo Hart An Icarus Films Release Produced by Adobe Productions International "Laugh out loud funny! Knocks the stuffy art off its pedestal and makes it an open, inclusive, and accessible experience. This spirited doc shows how much better art—and life—can be when everyone is invited to the party." —POV Magazine (718) 488-8900 www.IcarusFilms.com LOGLINE A riotous, irreverent all-male comic ballet troupe, Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo challenges gender and artistic norms in the conservative world of ballet. SYNOPSIS Exploring universal themes of identity, dreams and family, Rebels on Pointe celebrates the legendary dance troupe Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo. The notorious all- male drag ballet company, commonly known as “The Trocks,” was founded in 1974 in New York City on the heels of the Stonewall riots and has since developed a passionate cult following around the world. The film juxtaposes intimate behind-the-scenes access, rich archives and history, engaging character driven stories, and dance performances shot in North America, Europe and Japan. Rebels on Pointe is a creative blend of gender-bending artistic expression, diversity, passion and purpose which proves that a ballerina can be an act of revolution… in a tutu. Rebels on Pointe introduces dancers that director Bobbi Jo Hart filmed for four years: Bobby Carter from Charleston, South Carolina; Raffaele Morra from Fossano, Italy; Chase Johnsey from Lakeland, Florida; and Carlos Hopuy is from Havana, Cuba. With personal histories impacted by the AIDS crisis and eventual growth of the LGBT civil rights movement, the film’s main characters share powerful and inspiring anecdotes about growing up gay, their relationships with their families, and their challenges in becoming professional ballerinas. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

Will Forego Millage Increase

25^ Volume 17, Issue 34 Lowell Area Readers Since 1893 Wednesday, July 7,1993 Along Main Street Performance Plus Oil School Board to seek Change Center site plan Headlee; will forego application approved millage increase by Marc Poptalek Contributing Writer were voiced by the Com- By Thad Kraus fed up with (axes," Esch said. mission, one was delivery Lowell Ledger Editor if the Headke is passed in Lowell's City Planning truck traffic and the other Cuts in staff and programs August, teachers, but not their Commisson approved a site was what will be done in have become as much a part support staffs, would be plan application for a Per- case of possible oil spills. of Lowell Schools over the brought back for the 1993-94 formance Plus Oil Change Dean Lonick, from the past two years as pop quizzes school year, class loads would BIMINI BROTHERS BASH IN HONOR OF Center at West Main St. PlanningCommission, was and the first day. be increased, transportation SUSANNE TIMPSON-WITTENBACH The Commission concerned that "this stretch It's a hat trick of sorts (three services would be reduced by In honor of Sue Timpson-Witlcnbach, Club Eastbrook unanimously approved the of road is infamous for ac- straight years of cuts), Lowell 20 percent (students would be presents a Bimini Brothers Bash, Friday night July 16,1993. plan as presented by Ray cidents, nearly 100 a year, Superintendent Fritz Esch asked to walk further to bus A five dollar donation will go towards supporting Silent DeMeester and Kim how will the trucks coming wishes the school district slops); parents would be asked Observer. -

Download This Issue (PDF)

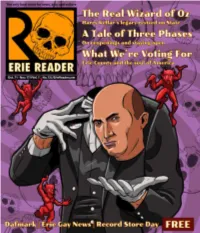

On behalf of the working people of Erie, IUPAT District Council 57 endorses: JOE BIDEN JOSH SHAPIRO KRISTY GNIBUS For President For Attorney General For Congress THESE CANDIDATES SHARE WORKING PEOPLE’S VALUES: FOR WORKERS’ FOR AFFORDABLE FOR FUNDING RIGHTS HEALTHCARE PUBLIC EDUCATION President Trump has • BROKEN HIS PROMISE ON INFRASTRUCTURE • PLANNED TO DEFUND HEALTHCARE • TAKEN THE CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHT OF COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AWAY FROM WORKERS • GIVEN TAX BREAKS TO LARGE CORPORATIONS DURING A PANDEMIC, WHILE OUR MOM AND POP SHOPS CONTINUE TO SUFFER Your livelihood for the next 4 years is on the line. Vote for candidates who will choose helping your family over fattening their wallets. WE CAN BE THE CHANGE Paid for by the IUPAT Political Action Together Political Committee, Hanover, MD CONTENTS From the Editors The only local voice for news, arts, and culture. OCTOBER 21, 2020 On keeping our heads on On behalf of the working people of Erie, Editors-in-Chief y most accounts, Erie-born magician Brian Graham & Adam Welsh Harry Kellar had an exceptionally good Managing Editor IUPAT District Council 57 endorses: Nick Warren What We’re Voting For – 5 Bhead on his shoulders. Throughout his standard-setting career, he demonstrated sav- Copy Editor Erie County and the soul of America Matt Swanseger vy, dignity, and class, while never forgetting where he came from. But despite his fami- Contributing Editors Still Making an Impression – 6 Ben Speggen ly-friendly reputation, he wasn’t above a lit- Jim Wertz Dafmark Dance Theater celebrates 30 years in tle shock value. For instance, detaching that Contributors Erie distinguished dome of his in front of a paying Liz Allen crowd of men, women, and children of all ages.