Multi-Channel Grocery Retail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Notices & the Courts

PUBLIC NOTICES B1 DAILY BUSINESS REVIEW TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2021 dailybusinessreview.com & THE COURTS BROWARD PUBLIC NOTICES BUSINESS LEADS THE COURTS WEB SEARCH FORECLOSURE NOTICES: Notices of Action, NEW CASES FILED: US District Court, circuit court, EMERGENCY JUDGES: Listing of emergency judges Search our extensive database of public notices for Notices of Sale, Tax Deeds B5 family civil and probate cases B2 on duty at night and on weekends in civil, probate, FREE. Search for past, present and future notices in criminal, juvenile circuit and county courts. Also duty Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach. SALES: Auto, warehouse items and other BUSINESS TAX RECEIPTS (OCCUPATIONAL Magistrate and Federal Court Judges B14 properties for sale B8 LICENSES): Names, addresses, phone numbers Simply visit: CALENDARS: Suspensions in Miami-Dade, Broward, FICTITIOUS NAMES: Notices of intent and type of business of those who have received https://www.law.com/dailybusinessreview/public-notices/ and Palm Beach. Confirmation of judges’ daily motion to register business licenses B3 calendars in Miami-Dade B14 To search foreclosure sales by sale date visit: MARRIAGE LICENSES: Name, date of birth and city FAMILY MATTERS: Marriage dissolutions, adoptions, https://www.law.com/dailybusinessreview/foreclosures/ DIRECTORIES: Addresses, telephone numbers, and termination of parental rights B8 of those issued marriage licenses B3 names, and contact information for circuit and CREDIT INFORMATION: Liens filed against PROBATE NOTICES: Notices to Creditors, county -

Firm Inventory Report ‐ July 2021

Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Food Safety Program ‐ Firm Inventory Report ‐ August 2021 Ret = Retail Food Establishment Mfg = Manufacturer Whse = Warehouse FM = Farmers Market Fi Firm Name Firm Address Locality Ret Mfg Whse FM r 6487 Church ST Chincoteague Island, # ALB Macarons Accomack County ‐ MFG ‐ ‐ VA 23336 # Alleluia Supermarket 24387 Lankford HWY Tasley, VA 23441 Accomack County RETAIL ‐ ‐ ‐ # Becca's Cakes & More 20161 Sunnyside DR Melfa, VA 23410 Accomack County ‐ MFG ‐ ‐ 29665 Burton Shore RD Locustville, VA # Big Otter Farm (home operation) Accomack County ‐ MFG ‐ ‐ 23404 4522 Chicken City RD Chincoteague # Black Narrows Brewing Co. Accomack County RETAIL MFG ‐ ‐ Island, VA 23336 # Bloxom Mini Mart 25641 Shoremain DR Bloxom, VA 23308 Accomack County RETAIL ‐ ‐ ‐ # Bloxom Vineyard 26130 Mason RD Bloxom, VA 23308 Accomack County ‐ MFG ‐ ‐ # Blue Crab Bay Co. 29368 Atlantic DR Melfa, VA 23410 Accomack County ‐ MFG ‐ ‐ 6213 Lankford HWY New Church, VA # Bonnie's Bounty Accomack County RETAIL ‐ ‐ ‐ 23415 6506 Maddox BLVD located inside # Candylicious Accomack County RETAIL ‐ ‐ ‐ Maria's Chincoteague Island, VA 23336 # Carey Wholesales 15383 Lankford HWY Bloxom, VA 23308 Accomack County ‐ ‐ WHSE ‐ # Cheers 25188 Lankford HWY Onley, VA 23418 Accomack County RETAIL ‐ ‐ ‐ # Chincoteague Farmers'Mark 4103 Main ST Chincoteague, VA 23336 Accomack County ‐ ‐ ‐ FRM_MKT # Chincoteague Fisheries Inc 4147 Main ST Chincoteague, VA 23336 Accomack County ‐ MFG ‐ ‐ 6060 Old Mill LN Chincoteague Island, # ChincoteagueMade -

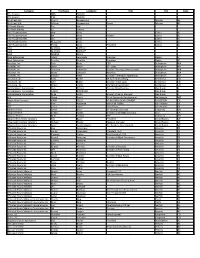

Meat Handlers by Name

Meat Handlers By Name Firm/Individual Name Address City Zip Code Registration # Ꞛ Farm (F) 3607 Jake Drive McLeansville, 27301 2362 3 Kids Farm (F) 2917 Piney Grove Wilbon Road Holly Springs, 27540 2211 3 M Livestock (F) 782 Ball Branch Road Boone, 28607 2189 3 Pastures Farm (F) 3232 Mount Olive Church Road Sophia, 27350 2616 37 Roots Farm (F) 4207 NC Hwy 47 Lexington, 27292 2197 3M Boer Goat Farm (F) 782 Borden Rd. Carthage, 28327 960 4 M Farms, LLC (F) 1617 McCuiston Dr. Burlington, 27215 1017 4440 Ranch and Cattle Company (F) 2985 Poovey's Chapel Church Rd. Hudson, 28638 2394 4J Cattle Company (F) 125 N. Morgan Street Shelby, 28150 2372 5 Strands Farm, LLC (F) 517 Ogburn Mill Rd. Stokesdale, 27357 2450 5G Farms (F) 6249 William Chapel Church Rd. Elm City, 27822 2570 7 Stands Farm (F) 1885 Middle Ford Rd. Hays, 28635 2689 8th Generation Farm (F) 190 Ironwood Dr. Rockwell, 28138 2602 A & G Farms (F) 75 Pace Rd. Hendersonville, 28792 2389 A & M Farm, Inc. (F) 2210 SE Railroad St. Granville, 27834 1698 A Fairview Farm (F) 3053 Fairview Farm Road Asheboro, 27205 2172 A Patch of Heaven Sheep Farm (F) 1960 Highway 274 Cherryville, 28021 1249 A Way of Life Farm (F) 856 Brooks Rd. Bostic, 28018 837 ABC Meats/Thoms Creek Farm, LLC (F) 6811 Oak Grove Church Rd. Mebane, 27302 2204 Acorn Farms, Inc. (F) 350 Curlee Rd. Polkton, 28135 1875 Acosta Foods, LLC (D) 116 West Central Ave. Asheboro, 27203 2700 Adam Taylor Farms (F) 4760 NC Hwy 801 Woodleaf, 27054 2576 Adams Wholesale Company 101 Nashville Company Rocky Mount, 27802 232 Adelphos Farms (F) 199 Carolina Cove Trail Low Gap, 27024 2331 ADUSA Distribution Center #04 2940 Arrowhead Road Dunn, 28334 2159 ADUSA Distribution Center #9 1703 East D Street Butner, 27509 2153 Affordable Freezer Beef (F) 5115 Airport Road Bear Creek, 27207 1777 Against the Grain Farm (F) 619 Camp Joy Rd. -

Participating Distributors Revised 05.26.15 Page 1 of 13

Participating Distributors Revised 05.26.15 Page 1 of 13 Recently Added Distributors Blair’s Market Dick’s TDL Group Corp (Tim Hortons) Blazer’s Fresh Foods DJ’s Inc Calgary Food Bank Blue Mountain Foods DJ’s Pilgrim Market The North West Company Bob’s Supermarket Don’s Market M&M Meat Shops Ltd. Bob’s Valley Don’s Thriftway T.I.G.O. Trading Bowman’s Double D Market Devash Farms Bradley’s Bestway Dove Creek Superette KCCP Distribution Company Broulim’s Market Downey Food Center Nutricion Fundemental Burney & Company Dry Creek Stations Pasquier Busy Corner Market Duane’s Foodtown Horizon Distributors Ltd. Buy Low Market Duckett’s Market Fruiticana Produce Ltd. Cactus Pete’s Country Store El Mexicano Market Dollarama L.P. Caliente Store El Rancho Market Camas Creek Country Store El Rodeo Market 99 Cents Only Stores Canyon Foods Elgin Foodtown Affiliated Foods Midwest Carter’s Market Emigrant General Store Affiliated Foods Inc - Amarillo Cash and Carry Foods Etcheverry’s Foodtown Ahold Cedaredge Foodtown F T Reynolds American Sales Company Central Market Familee Thriftway Giant Foods Chappel’s Market Family Foods Martin’s Foods Chuck Wagon General Family Market Stop & Shop Clarke’s Country Market Farmer’s Corner Albertson’s LLC Clark’s Market Farmer’s Market ACME Clinton Market Finley’s Food Farm Aldi Colter Bay Store Flaming George Market Asian Imports/Navarro Transportation Columbine Market Food Ranch Bestway Associated Food Stores (Far West) Cook’s Foodtown Food RoundUp A&A Market Cooperative Mercantile Corp Food World Thriftway Adamson’s Corner Market Fortine Merc. Alamo Store Cottonwood Market Fresh Approach Aldapes Market Cottonwoods Foods Fresh Market Allen’s Inc. -

UFCW International Convention Focuses on 'Unity, Family

Spring/Summer 2018 SCHOLARSHIP WINNERS 2018 UFCW International Convention focuses n May, eight students were The 2018 Irv R. String Scholarship honored with scholarships from Fund recipients are: on ‘Unity, Family, Local 152 at the 6th Annual Irv R. String Scholarship Fund Connor Devosa Community, Worth’ Banquet and Awards Night. His father, Stephen Devosa, is a rought together by the core I“Local 152 believes in the value member at Saker ShopRite. values of “Unity, Family, of hard work,” Local 152 President Kayla Devosa Community and Worth,” Brian String said. “We’re happy to be thousands of union members able to reward the hard work of these Her father, Stephen Devosa, is a gathered this spring for the UFCW students and to give them a helping hand member at Saker ShopRite. B Please see page 6 as they continue to pursue their dreams.” Please see page 2 Also inside: Member Marylyn Graham’s amazing volunteer service • Manufacturing & health care updates Buy Scholarship recipients 2018 American! Continued from front page Leslie Morris Catherine Faust Her mother, Medora Morris, is a member at Monmouth County Sheriff’s Office. Visit Her mother, Abigayle Faust, is a americansworking.com member at Acme Markets. Mitchell Remondi Nicholas Klaptach for information on finding His father, James Remondi, is a member Nicholas is a member at Village at Kraft Foods in Dover, Del. American-made products. ShopRite in Galloway, N.J. Support U.S. workers Elena St. Amour Marybeth McNamee and help save jobs! Elena is a member of at Incollingo’s Her father, Daniel McNamee, is a Family Markets in Egg Harbor City, N.J. -

Lidl's Proposed Development at Banister Road, Southampton

Lidl’s proposed development at Banister Road, Southampton Brochure for Southampton City Council Planning & Rights of Way Panel – 27 August 2019 Planning application for a Lidl foodstore with parking, landscaping and access works Planning application number: 18/01532/FUL Lidl GB Limited 1. Executive summary Planning Committee members will have the final vote on Lidl’s planning application for a Is acceptable in terms of planning policy new discount foodstore on Banister Road on 27th August 2019. The proposal site was The site is previously used brownfield land that has a long previously used for car sales and occupied by history of commercial and quasi-retail use. It is not allocated HA Fox Jaguar and Hunter Landrover until it for any specific use in the development plan and it’s use by was purchased by Lidl in December 2018. Lidl has been assessed and considered acceptable in terms of the sequential and other retail impact tests. The development that you will be voting upon has been subject to extensive negotiations over the past “The principle of a new Lidl store is policy compliant twelve months. Changes have been made following and would be a suitable addition to the locale.” feedback from the local community, statutory Committee Report – paragraph 7.1 consultees and officers of the Council. The proposed discount foodstore will bring many th benefits to this area of the city. On Tuesday 27 August Is acceptable in highways terms 2019, Councillors on the Planning and Rights of Way Panel will have the final vote on an application that: A full transport assessment has been undertaken to examine the acceptability of the site access; parking Has secured a recommendation for APPROVAL provision and the impact on traffic flows and junctions. -

Membership List.Xlsm

Membership Directory by Member Name Membership Tier Member Name Main Individual Phone Number Category Chair's Circle Bridge Public Affairs Mr. Todd Womack (423) 771-4272 Government Relations President's Club ASTEC Mr. Barry Ruffalo (423) 899-5898 Construction President's Club BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee Mr. Roy D. Vaughn (423) 535-5600 Insurance President's Club Chambliss, Bahner & Stophel, PC Mr. Mark A. Cunningham (423) 756-3000 Attorneys/Legal Services President's Club Chattanooga Gas Company Mr. Paul Teague (423) 490-4232 Gas Companies President's Club Chattanooga State Community College Dr. Rebecca Ashford (423) 697-4400 Education President's Club Chattanooga Times Free Press Mr. Jeff DeLoach (423) 756-6900 News/Publications President's Club CHI Memorial Health System Ms. Janelle Reilly (423) 495-2525 Healthcare - Hospitals President's Club City of Chattanooga The Honorable Tim Kelly (423) 643-7800 Government President's Club EPB Mr. David Wade (423) 648-1372 Electric Companies President's Club Erlanger Health System Dr. William L. Jackson, MD, MBA (423) 778-7000 Healthcare - Hospitals President's Club First Horizon Bank Mr. Jay Dale (423) 757-4011 Financial - Banks President's Club Fletcher Bright Company Mr. Scott Williamson (423) 755-8830 Real Estate/Realtors President's Club Hamilton County Government The Honorable Jim M. Coppinger (423) 209-6100 Government President's Club JPMorgan Chase Ms. Stefanie Mansueto (423) 242-4731 Financial - Banks President's Club Miller & Martin PLLC Mr. James M. Haley, IV (423) 756-6600 Attorneys/Legal Services President's Club Parkridge East Hospital Mr. Will L. Windham, MHA (423) 855-3500 Healthcare - Hospitals President's Club Parkridge Health System Mr. -

Certified Plant Dealers

Certified Plant Dealers License County Operation Type Number ERIE Drug Store CATTARAUGUS Other CHENANGO Roadside Stand DELAWARE Grocery Store ERIE Other ERIE Roadside Stand HAMILTON Grocery Store KINGS Grocery Store KINGS Drug Store NASSAU Hardware Store NASSAU Dept. Store NEW YORK Drug Store ORANGE Other RENSSELAER Other SUFFOLK Hardware Store SUFFOLK Landscaper Page 1 of 1252 09/26/2021 Certified Plant Dealers Trade Name Owner Name WALGREENS #10443 WALGREEN EASTERN COMPANY INC. HILLSIDE ACRES GIAMBRONE FRANCIS FROG POND LLC SEAN & KAREN NOXON KENS COUNTRY SHEDS KENNETH STANTON FAMOUS HORSERADISH SKUP ZENON THE MAIZE MAIZE ADK TRADING POST WILLIAM S SANDIFORD ALDI INC #7 ALDI INC RITE AID #3888 RITE AID OF NEW YORK INC SBS HARDWARE RASHEED ALLI TJ MAXX STORE #1478 TJ MAXX CVS PHARMACY # 2671 CVS ALBANY LLC PETVALU # 5610 BRUEK WOLGENMOTH PETSMART INC #1589 PETSMART INC LOWE'S HOME CTR #3159 LOWES HOME CENTERS LLC VICKHAMPTONS INC VICKHAMPTONS INC Page 2 of 1252 09/26/2021 Certified Plant Dealers Street Number Street Name Address Line 2 Address Line 3 3564 DELEWARE AVENUE 9777 RT 242 2001 STATE HIGHWAY 7 339 KNOX AVE 999 BROADWAY-BROADWAY MARKET 3901 NIAGARA FALLS BOULEVARD 1601 TUPPER RD 528 GATEWAY DRIVE 9738 SEA VIEW AVENUE 455 NASSAU RD 300 PENINSULA BLVD 750 AVENUE OF AMERICAS 36 ROUTE 9 WEST SUITE 1A 279 TROY ROAD 100 LONG ISLAND EXPRESSWAY 394 COUNTY ROAD 39 Page 3 of 1252 09/26/2021 Certified Plant Dealers NYS Municipal City State Zip Code Georeference Boundaries KENMORE NY 14217 LITTLE VALLEY NY 14755 POINT (-78.87032 351 42.208287) -

The Australian Supermarket Sector – Competition and Disruption: a Perspective

The Australian Supermarket Sector – Competition and Disruption: A Perspective December 2015 The Australian supermarket industry is one of the largest, most competitive industries in Australia (IBISWorld, 2014). The Industry revenue is projected to grow by 2.3% annualised over the next five years to reach $91.6 billion, including a forecast growth of 2.6% in 2014-15 (IBISWorld, 2014). Global companies, like Aldi and Costco, have shifted the dynamics of the industry. The introduction of Aldi in 2001 meant the introduction of private label merchandise, with Woolworths and Coles implementing private-label merchandise as a cost-reduction method (Grant, Butler, Orr & Murray, 2014). However, changes in the grocery sector have been unfolding relatively quickly during 2015. ALDI’s expansion and the announcement that Lidl will be opening in Australia has threatened the duopoly to Coles and Woolworths, as well as to the shrinking market share for Metcash’s IGA chain and independent retailers. The best overview of the grocery sector in Australia is gained when looking at the industry dynamics in each of the states. The figure below demonstrates the significant differences in market share for some of the major participants, and it also shows that the four major companies in the sector control at least 85% of the total market spend. The Blenheim Report | No Limitations 2 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE LATIN AMERICA MIDDLE EAST AFRICA NORTH AMERICA In a report by Roy Morgani, the change in the competitive landscape in the grocery sector can be seen due to the expansion of ALDI. ALDI has grown its market share from 3.1% to 11.6% in 2015. -

2013 List of Registrants

Company FirstName LastName Title City State 4T's Grocery ANN TAYLOR 4T's Grocery TIM TAYLOR 5th Street IGA Sherry Huenemann Minden NE 5th Street IGA William Huenemann Owner Minden NE 99 Ranch Market Tee Jaw 99 Ranch Market Ty Truong A & R Supermarkets Ann Davis Calera AL A & R Supermarkets Bill Davis Partner Calera AL A & R Supermarkets Jan Davis Calera AL A & R Supermarkets Margarita Davis Calera AL A & R Supermarkets Phillip Davis President Calera AL AAIA MICHAEL BARRATT AAIA MICHAEL BARRATT AAIA ARLENE DAVIS Abco Enterprises Adam Sepulveda Manager Ogden VT Abco Enterprises Suzette Sharifan President Ogden VT Accelitec, Inc. Tom Bartz CEO Bellingham WA Accelitec, Inc. Steve Byron VP - Sales Bellingham WA Accelitec, Inc. Christine Schneider Director -Business Development Bellingham WA Accelitec, Inc. Marty Schroder Accelitec Bellingham WA Accelitec, Inc. Edward West Director - Merchant Operations Bellingham WA AccuCode, Inc. Todd Baillie VP Sales & Marketing Centennial CO AccuCode, Inc. John Butler Director of AO: Apps Centennial CO AccuCode, Inc. Robyn Crotty Marketing Coordinator Centennial CO Ace Hardware Corporation Curt DeHart Director New Business Oak Brook IL Ace Hardware Corporation CARLO MORANDO Oak Brook IL Ace Hardware Corporation Mike Smith Grocery Channel Manager Oak Brook IL ACS Chuck Daniel Dir of Corporate Development Nottingham MD Action Retail Services JOHN GILLIS VP BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT FULLERTON CA ADT Teal Hausman Jack of all Trades San Antonio TX ADT Cesar Lopez Sales/Buyer San Antonio TX Advance Pierre David Minx VP Strategic Sourcing Cincinnati OH Advance Pierre Shawn Sparks Director of Strategic Sourcing Enid OK Advance Pierre Mike Zelkind SVP Cincinnati OH Advanced Inventory Solutions Tim Bayer President Grand Rapids MI Advanced Inventory Solutions Richard Heetai Regional Manager Grand Rapids MI Advanced Inventory Solutions Steve Southerington Dir. -

Abbeville Calhoun

Abbeville Calhoun ARABI Super 1 National Infusion BOUTTE LOUISIANA Services C & C Drugs Sav-More Drugs BATON ROUGE 5344 Brittany Dr. 7540 W. Judge Perez Dr. (225)766-7828 Hwy 90W ABBEVILLE (504)279-0446 Albertsons (985)785-2145 Pinnacle Pharmacy Cashway Pharmacy Of Rite Aid Bolton Health Mart Services Abbeville Pharmacy 5425 Brittany Dr., Ste. B BOYCE 2509 Charity St. Winn-Dixie 2958 Perkins Rd. (225)761-9111 Boones Pharmacy (337)893-2131 (225)343-4869 511 Ulster St. ARCADIA Rite Aid Eckerd Drugs Bordelons Super Save (318)793-2400 Chris Cole Pharmacy Pharmacy Safescript Rite Aid 800 1st St. 6920 Plank Rd. Target BREAUX BRIDGE Thrifty Way Pharmacy (318)263-2916 (225)356-0253 2640 North Dr. Walgreens Boyer's Thrift Pharmacy Fred's Pharmacy Central Drug Store 1423 Henderson Hwy. (337)893-6304 Winn-Dixie New Arcadia Health Mart 13561 Hooper Rd. (337)228-2064 Walgreens 1982 N. Railroad Ave. (225)262-6200 BENTON Healthmart Pharmacy Winn-Dixie (318)263-2919 Community Pharmacy 240 W. Mills Ave., Ste. 105 Brookshire Pharmacy 8818 Scotland Ave. (337)332-3470 ABITA SPRINGS ARNAUDVILLE (225)775-6337 BERNICE Herbert's Discount Abita Pharmacy Hardys Drug Store Coursey Urgent Care Pharmacy 22107 B Hwy. 36 123 Fuselier St. 13702 Coursey Blvd., Bldg. 10 Bernice Pharmacy 1101 Grandpoint Ave. (985)875-9906 (337)754-5231 (225)755-1400 419 Main St. (337)332-5186 (318)285-9521 Stoute's Thrifty Way Eckerd Drugs Hollier's Family Pharmacy ALEXANDRIA Pharmacy Hatley's Pharmacy Infinity Health Care 1456 E. Bridge St. 412 Olive St. 1210 Hwy. -

Smiles for Everybody!

VOL. 8 NO. 21 Visit TapIntoMahopac.net for the latest news. THURSDAY, JULY 19, 2018 Smiles Iconic Mahopac Falls for everybody! business changes hands Red Mills Market sold as longtime owners retire BY BOB DUMAS Jedlicka’s parents rst opened he wanted to go into the family EDITOR the store in 1960 just down the business. road from where the business is “I enjoy people and that is After more than ve decades currently situated. At that time, what it is all about when you of service to the community, it was known as the Mahopac are in retail. You have to be a an iconic Mahopac business is Falls Store. people person,” he said. “In big changing hands. “We grew out of that and stores, you are treated terribly; Red Mills Market on South needed more space,” Jedlicka they don’t say hello or smile. My Lake Boulevard in Mahopac said. “In 1966, the opportunity employees were always taught Falls was sold on June 28. came up to buy the land and so to say ‘good morning’ and ‘have Its longtime owners, Ron we did and built the new store a great day.’ Just by being upbeat and Regina Jedlicka, decided to there.” like that, you are going to feel retire and sold the business to Jedlicka’s father got started better about yourself.” Alex Dabashi, and his brother, in the grocery industry work- Jedlicka said that is why his Tommy, and his dad, Musleh, ing for the now-defunct chain small mom-and-pop grocery who were the franchise own- known as Daniel Reeves Stores was able to thrive for more than ers of the Key Food store in the (it merged with Safeway).