Eddie Daniels & Roger Kellaway Kermit Ruffins Charnett Moffett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Highly Recommended New Cds for 2018

Ed Love's Highly Recommended New CDs for 2018 Artist Title Label Dave Young and Terry Promane Octet Volume Two Modica Music Phil Parisot Creekside OA2 John Stowell And Ulf Bandgren Night Visitor Origin Eric Reed A Light In Darkness WJ3 Katharine McPhee I Fall In Love Too Easily BMG Takaaki Otomo New Kid In Town Troy Dr. Lonnie Smith All In My Mind Blue Note Clovis Nicolas Freedom Suite Ensuite Sunnyside Wayne Escoffery Vortex Sunnyside Steve Hobbs Tribute To Bobby Challenge Adam Shulman Full Tilt Cellar Live` Scott Hamilton Live At Pyat Hall Cellar Live Keith O’ Rourke Sketches From The Road Chronograph Jason Marsalis Melody Reimagined Book One Basin Street 1 Ed Love's Highly Recommended New CDs for 2018 Artist Title Label Dan Block Block Party High Michael Waldrop Origin Suite Origin Roberto Margris Live In Miami J Mood Dan Pugach Nonet Plus One Unit UTR Jeff Hamilton Live From San Pedro Capri Phil Stewart Melodious Drum Cellar Live Ben Paterson That Old Feeling Cellar Live Jemal Ramirez African Skies Joyful Beat Michael Dease Reaching Out Positone Ken Fowser Don’t Look Down Positone New Faces Straight Forward Positone Emmet Cohen With Ron Carter Masters Legacy Series Volume Two Cellar Live Bob Washut Journey To Knowhere N/C Mike Jones and Penn Jillette The Show Before The Show Capri 2 Ed Love's Highly Recommended New CDs for 2018 Artist Title Label Dave Tull Texting And Driving Toy Car Corcoran Holt The Mecca Holt House Music Bill Warfield For Lew Planet Arts Wynton Marsalis United We Swing Blue Engine Scott Reeves Without A Trace Origin -

UWE Obergs LACY POOL Uwe Oberg Piano / Rudi Mahall Clarinets / Michael Griener Drums

UWE OBERGs LACY POOL Uwe Oberg piano / Rudi Mahall clarinets / Michael Griener drums Just released! LACY POOL_2 (Leo Records / London) LACY POOL was founded by German pianist Uwe Oberg. With an intriguing lineup with the Berlin-based clarinettist Rudi Mahall and drummer Michael Griener, the band explores different styles in Steve Lacy's music and Oberg's compositions. It's a joyful celebration as well as an deconstruction, that transfers the Lacy's pieces into the present. Fresh and inquisitive. JAZZWEEKLY July 2017 “On Lacy Pool, an intriguing lineup (piano-trombone-drums) revisit what might one day become standards - 10 compositions penned by Steve Lacy. Uwe Oberg's angular lines, Christof Thewes' soaring trombone and drummer Michael Griener's clever support help bring out the joy that inhabits those pieces. Their truculent nods at Dixieland or Thelonious Monk are a reminder of how both influences informed the late soprano sax player's development. They never get lost in a meditative state, because Oberg and company's mood is definetely more celebratory than mournful. To sum up, this is an excellent addition to the recent tributes paid to Lacy's legacy that will surely inspire more generations to come. DOWNBEAT, December 2010 Great players, luminously entertaining album. TOUCHING EXTREMES, Okt. 2010 Confirming that the music of a true original like Lacy is best celebrated by adding to it rather than copying, the three leap into the Lacy Pool at the deep end. Accepting this challenge, they still manage an Olympic medal-like performance. KEN WAXMAN, March 2010 This refreshing and innovative, forward-thinking look on Steve Lacy's music is imaginatively clever as it is delightful. -

JAMU 20160316-1 – DUKE ELLINGTON 2 (Výběr Z Nahrávek)

JAMU 20160316-1 – DUKE ELLINGTON 2 (výběr z nahrávek) C D 2 – 1 9 4 0 – 1 9 6 9 12. Take the ‘A’ Train (Billy Strayhorn) 2:55 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra: Wallace Jones-tp; Ray Nance-tp, vio; Rex Stewart-co; Joe Nanton, Lawrence Brown-tb; Juan Tizol-vtb; Barney Bigard-cl; Johnny Hodges-cl, ss, as; Otto Hardwick-as, bsx; Harry Carney-cl, as, bs; Ben Webster-ts; Billy Strayhorn-p; Fred Guy-g; Jimmy Blanton-b; Sonny Greer-dr. Hollywood, February 15, 1941. Victor 27380/055283-1. CD Giants of Jazz 53046. 11. Pitter Panther Patter (Duke Ellington) 3:01 Duke Ellington-p; Jimmy Blanton-b. Chicago, October 1, 1940. Victor 27221/053504-2. CD Giants of Jazz 53048. 13. I Got It Bad (And That Ain’t Good) (Duke Ellington-Paul Francis Webster) 3:21 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra (same personnel); Ivie Anderson-voc. Hollywood, June 26, 1941. Victor 17531 /061319-1. CD Giants of Jazz 53046. 14. The Star Spangled Banner (Francis Scott Key) 1:16 15. Black [from Black, Brown and Beige] (Duke Ellington) 3:57 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra: Rex Stewart, Harold Baker, Wallace Jones-tp; Ray Nance-tp, vio; Tricky Sam Nanton, Lawrence Brown-tb; Juan Tizol-vtb; Johnny Hodges, Ben Webster, Harry Carney, Otto Hardwicke, Chauncey Haughton-reeds; Duke Ellington-p; Fred Guy-g; Junior Raglin-b; Sonny Greer-dr. Carnegie Hall, NY, January 23, 1943. LP Prestige P 34004/CD Prestige 2PCD-34004-2. Black, Brown and Beige [four selections] (Duke Ellington) 16. Work Song 4:35 17. -

Bob James and Nancy Stagnitta "In the Chapel in the Moonlight"

Interlochen, Michigan * Bob James and Nancy Stagnitta "In the Chapel in the Moonlight" Saturday, March 4, 2017 2:30pm, Dendrinos Chapel/Recital Hall 7:30pm, Dendrinos Chapel/Recital Hall PROGRAM Nancy Stagnitta, flute Bob James, piano Side A Dancing on the Water ............................................................................................ Bob James Air Apparent .................................................................... Johann Sebastian Bach/Bob James J.S. Bop ................................................................................................................. Bob James Quadrille ................................................................................................................ Bob James Heartstorm ............................................................................................................. Bob James ~ BRIEF PAUSE ~ Side B Smile .............................................................................................................. Charlie Chaplin The Bad and the Beautiful .................................................................................. David Raksin Iridescence ............................................................................................................ Bob James Bijou/Scrapple from the Chapel ................................................... Bob James/Nancy Stagnitta Odyssey ................................................................................................................. Bob James All compositions arranged by Bob -

P:\Pag\20220528\Summer\Section\T\15

TRAVERSE CITY RECORD-EAGLE SUMMER GUIDE 2004 15 NITELIFE GUIDE Jazz composer expands creations, talents BY MARTA HEPLER DRAHOS theme to the ‘70s television myself,” he says — it did Record-Eagle staff writer show “Taxi,” two Grammys inspire his latest venture, and a Lifetime Achievement With his international The Bob James Art of Wine Award from the Smooth career firmly entrenched, Collection. Launched in Jazz Association of Bob James could live any- 2002 after a chance meeting America, and several Gold where in the world. with Australian beverage Records. But Traverse City is where entrepreneur Chris Payne, These days he spends the jazz pianist and compos- the signature collection fea- about half his time perform- er feels a creative vibe. tures James’ distinctive art ing in the U.S., Europe and “We like privacy, peace on its labels. Asia, and the other half and quiet,” said James, who So far the collection con- recording in various set- has vacationed in the area sists of three wines from tings. Never one to focus on for more than 20 years. “I Down Under, including a single project when he think there’s a feeling we “Smooth Chardonnay,” win- could be working on three get here, there’s an escape ner of a silver medal at the or four, he laid down tracks aspect to it.” first U.S. Starwine for a new album with his Since purchasing part of International Wine jazz super-group Fourplay the Long Lake retreat estate Competition in in February, the same of meat company magnate J. Philadelphia in March. -

Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zachary Streeter

Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zachary Streeter A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Jazz History and Research Graduate Program in Arts written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and Dr. Henry Martin And approved by Newark, New Jersey May 2016 ©2016 Zachary Streeter ALL RIGHT RESERVED ABSTRACT Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zach Streeter Thesis Director: Dr. Lewis Porter Despite the institutionalization of jazz music, and the large output of academic activity surrounding the music’s history, one is hard pressed to discover any information on the late jazz guitarist Jimmy Raney or the legacy Jimmy Raney left on the instrument. Guitar, often times, in the history of jazz has been regulated to the role of the rhythm section, if the guitar is involved at all. While the scope of the guitar throughout the history of jazz is not the subject matter of this thesis, the aim is to present, or bring to light Jimmy Raney, a jazz guitarist who I believe, while not the first, may have been among the first to pioneer and challenge these conventions. I have researched Jimmy Raney’s background, and interviewed two people who knew Jimmy Raney: his son, Jon Raney, and record producer Don Schlitten. These two individuals provide a beneficial contrast as one knew Jimmy Raney quite personally, and the other knew Jimmy Raney from a business perspective, creating a greater frame of reference when attempting to piece together Jimmy Raney. -

Downbeat-2-19-Soul-Fingers-Pages

Jazz / BY DENISE SULLIVAN MAGNUS CONTZEN Draksler/Eldh/Lillinger Punkt.Vrt.Plastik INTAKT 318 ++++ Bobby Broom The lineup of any ensemble has an alchemical quality to it. The right combination of personal- A Personalized Perspective ities and styles can yield nothing less than gold. Three trios and a quartet—led by a drummer, guitarist John Chiodini (Natalie Cole, Tony But throw in one bad element and it quickly can a guitarist, a keyboardist and a bassist, re- Bennet) and organist Joe Bagg (Madeleine turn leaden. spectively—demonstrate an ability to cast a Peyroux, Larry Coryell) through two pieces That was the risk drummer Christian wide net and still remain within the jazz tradi- by Brazilian musician César Camargo Maria- Lillinger and bassist Petter Eldh took when they tion. From originals to classic rock standards, no, plus a samba, “Cascades Of The 7 Water- started working with pianist Kaja Draksler in a soul, blues and a touch of Brazil, these play- falls” by Alex Malheiros, as well as the Chiod- new trio. The pair already were familiar with ers rely on their deep love and knowledge of ini-penned “Cheetahs And Gazelles,” with its one another, having provided the backbone for modes and material, and a commitment to own Brazilian changes. Seiwell was a found- the marvelous free-jazz quartet Amok Amor. laying it down. ing member of Paul McCartney’s Wings and Draksler was the X-factor they brought into their Known for his work on the Hammond there’s a dramatic version of “Live & Let Die” creative partnership, a new source of heat that B-3 organ, Raphael Wressnig lets loose included here, plus a guest appearance by on Chicken Burrito (Pepper Cake 2110; rocker Edgar Winter, who hits the saxophone could bend their playing into new shapes. -

Mesia Austin, Percussion Received Much of the Recognition Due a Venerable Jazz Icon

and Blo win' The Blues Away (1959), which includes his famous, "Sister Sadie." He also combined jazz with a sassy take on pop through the 1961 hit, "Filthy McNasty." As social and cultural upheavals shook the nation during the late 1960s and early 1970s, Silver responded to these changes through music. He commented directly on the new scene through a trio of records called United States of Mind (1970-1972) that featured the spirited vocals of Andy Bey. The composer got deeper into cosmic philosophy as his group, Silver 'N Strings, recorded Silver 'N Strings School of Music Play The Music of the Spheres (1979). After Silver's long tenure with Blue Note ended, he continued to presents create vital music. The 1985 album, Continuity of Spirit (Silveto), features his unique orchestral collaborations. In the 1990s, Silver directly answered the urban popular music that had been largely built from his influence on It's Got To Be Funky (Columbia, 1993). On Jazz Has A Sense of Humor (Verve, 1998), he shows his younger SENIOR RECITAL group of sidemen the true meaning of the music. Now living surrounded by a devoted family in California, Silver has Mesia Austin, percussion received much of the recognition due a venerable jazz icon. In 2005, the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (NARAS) gave him its President's Merit Award. Silver is also anxious to tell the Theresa Stephens, clarinet Brian Palat, percussion world his life story in his own words as he just released his autobiography, Let's Get To The Nitty Gritty. -

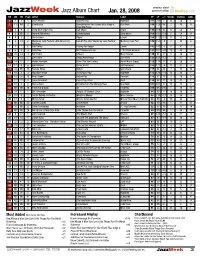

Jazzweek Jazz Album Chart Jan

airplay data JazzWeek Jazz Album Chart Jan. 28, 2008 powered by TW LW 2W Peak Artist Release Label TP LP +/- Weeks Stations Adds 1 1 1 1 Steve Nelson Sound-Effect HighNote 211 210 1 13 56 1 2 11 NR 2 Eliane Elias Something For You: Eliane Elias Sings & Blue Note 196 128 68 2 49 14 Plays Bill Evans 3 5 9 2 Deep Blue Organ Trio Folk Music Origin 194 169 25 15 52 1 4 2 NR 2 Hendrik Meurkens Sambatropolis Zoho Music 166 185 -19 2 54 13 5 4 2 2 Jim Snidero Tippin’ Savant 154 172 -18 11 53 1 6 6 33 6 Monterey Jazz Festival 50th Aniversary Live At The 2007 Monterey Jazz Festival Monterey Jazz Fest 145 154 -9 3 43 8 All-Stars 7 7 7 6 Bob DeVos Playing For Keeps Savant 142 145 -3 11 47 0 8 3 5 3 Andy Bey Ain’t Necessarily So 12th Street Records 137 182 -45 10 49 0 9 20 34 9 Ron Blake Shayari Mack Avenue 136 94 42 3 46 11 10 7 14 7 Joe Locke Sticks And Strings Jazz Eyes 132 145 -13 7 37 5 11 14 11 2 Herbie Hancock River: The Joni Letters Verve Music Group 125 114 11 17 50 0 12 12 8 8 John Brown Terms Of Art Self Released 123 127 -4 11 32 0 13 28 NR 13 Pamela Hines Return Spice Rack 117 84 33 2 43 14 14 10 3 3 Houston Person Thinking Of You HighNote 115 139 -24 13 38 2 15 18 38 15 Brad Goode Nature Boy Delmark 112 97 15 3 29 6 16 22 21 3 Cyrus Chestnut Cyrus Plays Elvis Koch 110 93 17 16 37 1 17 16 6 6 Stacey Kent Breakfast On The Morning Tram Blue Note 101 101 0 16 33 0 18 NR NR 18 Frank Kimbrough Air Palmetto 100 NR 100 1 36 31 19 24 11 1 Eric Alexander Temple Of Olympic Zeus HighNote 94 90 4 18 39 0 20 15 4 2 Gerald Wilson Orchestra Monterey -

TOM MALONEY and TOM HALL a Tribute to Four Important St

TOM MALONEY AND TOM HALL A Tribute to Four Important St. Louisans, BLUESWEEK Review in Pictures, An Essay by Alonzo Townsend, The Application Window Opens for the St. Louis/IBC Road to Memphis, plus: CD Review, Discounts for Members and more... THE BI-MONTHLY MAGAZINE OF THE SAINT LOUIS BLUES SOCIETY July/August 2014 Number 69 July/August 2014 Number 69 Officers Chairperson BLUESLETTER John May The Bi-Monthly Magazine of the St. Louis Blues Society Vice Chairperson The St. Louis Blues Society is dedicated to preserving and perpetuating blues music in Jeremy Segel-Moss and from St. Louis, while fostering its growth and appreciation. The St. Louis Blues Society provides blues artists the opportunity for public performance and individual Treasurer improvement in their field, all for the educational and artistic benefit of the general public. Jerry Minchey Legal Counsel Charley Taylor CELEBRATING 30 YEARS Secretary Lynn Barlar OF SUPPORTING BLUES MUSIC IN ST LOUIS Communications Dear Blues Lovers, Mary Kaye Tönnies Summer is in full swing in St. Louis.Festivals, neighborhood events and patios filled with Board of Directors music are kickin’ all over the City. Bluesweek, over Memorial Day Weekend, was a big hit for Ridgley "Hound Dog" Brown musicians and fans alike. Check out some of the pictures from the weekend on page 11. Thanks to Bernie Hayes everyone who helped make Bluesweek a success! Glenn Howard July means the opening of applications for bands and solo/duo acts who want to be involved Rich Hughes in this year’s International Blues Challenge. Last year we had a fantastic group of bands and solo/ Greg Hunt duo acts competing to go to Memphis. -

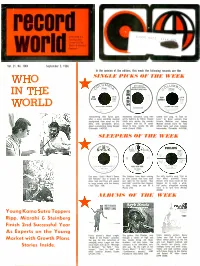

Ing the Fj Needs of the Music & Record Ti Ó+ Industry

. I '.k i 1 Dedicated To £15.o nlr:C, .3n0r14 Serving The fJ Needs Of The Music & Record ti Ó+ Industry ra - Vol. 21, No. 1004 September 3, 1966 In the opinion of the editors, this week the following records are the WHO SINGLE PICKS OF THE WEEK LU M MY UNCLE 6 USED TO LOVE IN THE ME BUT SHE DIED y 43192 WORLD JUST LIME A WOMAN Trendsetting Bob Dylan goes Absolutely nonsense song with Gentle love song, "A Time for after a more soothing musical gritty delivery by Miller. Should Love," by Oscar winners Paul background than usual on this catch ears across the country Francis Webster and Johnny ditty, with perceptive lyrics, as Roger, with his TV series Mandel should score for Tony about a precocious teeny bopper about to bow, recalls his odd whose taste and style remains (Columbia 4-43792). uncle (Smash 2055). impeccable (Columbia 4-43768). SLEEPERS OF THE WEEK PHILIPS Am. 7. EVIL ON YOUR MIND , SAID I WASN'T GONNAN TELL 0 00000 TERESA BREARE S AM t - DAVE A1 Duo does "Said I Wasn't Gonna The Uniques have been coming The nifty country song "Evil on Tell Nobody" like it should be up with sounds that have been Your Mind" provides Teresa done. Sam and Dave will appeal just right for the market. "Run Brewer with what could be her to large crowds with tfie bouncy and Hide" could be their biggest biggest hit in quite a while. r/ber (Stax 198). to date. Keep an eye on it Her perky, altogether winning (Paula 245). -

Duke Ellington-Bubber Miley) 2:54 Duke Ellington and His Kentucky Club Orchestra

MUNI 20070315 DUKE ELLINGTON C D 1 1. East St.Louis Toodle-Oo (Duke Ellington-Bubber Miley) 2:54 Duke Ellington and his Kentucky Club Orchestra. NY, November 29, 1926. 2. Creole Love Call (Duke Ellington-Rudy Jackson-Bubber Miley) 3:14 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. NY, October 26, 1927. 3. Harlem River Quiver [Brown Berries] (Jimmy McHugh-Dorothy Fields-Danni Healy) Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. NY, December 19, 1927. 2:48 4. Tiger Rag [Part 1] (Nick LaRocca) 2:52 5. Tiger Rag [Part 2] 2:54 The Jungle Band. NY, January 8, 1929. 6. A Nite at the Cotton Club 8:21 Cotton Club Stomp (Duke Ellington-Johnny Hodges-Harry Carney) Misty Mornin’ (Duke Ellington-Arthur Whetsol) Goin’ to Town (D.Ellington-B.Miley) Interlude Freeze and Melt (Jimmy McHugh-Dorothy Fields) Duke Ellington and his Cotton Club Orchestra. NY, April 12, 1929. 7. Dreamy Blues [Mood Indigo ] (Albany Bigard-Duke Ellington-Irving Mills) 2:54 The Jungle Band. NY, October 17, 1930. 8. Creole Rhapsody (Duke Ellington) 8:29 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. Camden, New Jersey, June 11, 1931. 9. It Don’t Mean a Thing [If It Ain’t Got That Swing] (D.Ellington-I.Mills) 3:12 Duke Ellington and his Famous Orchestra. NY, February 2, 1932. 10. Ellington Medley I 7:45 Mood Indigo (Barney Bigard-Duke Ellington-Irving Mills) Hot and Bothered (Duke Ellington) Creole Love Call (Duke Ellington) Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. NY, February 3, 1932. 11. Sophisticated Lady (Duke Ellington-Irving Mills-Mitchell Parish) 3:44 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra.