United States Code - Search - Result § 212

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DART Discussion Slated for March 9 Nities Throughout the Metro by J.W

INSIDE ., Six scholarships offered .Page4· Black Awareness Women in Leadership Conference activities Dr. Shei.. Simmons of Student Page4 Servlc" was one of many per formers who contributed to Black Awareness Month obser O_bservatory Open House PageS vance at UTD during February. The Black contribution In music, art, literature, dance, cinema and more was cele Showtime: ••Guys and Dolls" Page7 . brated In actlvltlet throughout the month. For the Mercury's wrap-up, see p-ge 2. UTD ERCURY. , The Student Newspaper of The University of Texas at Dallas Vol. 3 No. 11 -, Feb. 28, 1983 Film star Terry Jastrowto speak at UTD's March 19 conference Terry Jastrow, creator and per person. For registration in Jeffrey C. Barbakow, a spe star of the film "Waltz Across formation. call 690-2204. cialist in entertainment fi Texas," will offer observations President of his own Los nancing for Merrill Lynch White and advice on breaking into the Angeles film production com Weld Capital Markets Group, film industry Saturday, March pany, Jastrow worked as a pro will discuss "Motion Picture 19 in Dallas as keynote speaker ducer-director for ABC Sports Financing"; David Comsky, a for UTD's third annual Motion and appeared in two feature Beverly Hills attorney special Picture Production Confer films, numerous television izing in the legalities of film ence. shows and five stage plays be making, will answer the ques He plans to explain how to fore writing and co-starring tion, ''What Is Hollywood Really develop and carry through a with his wife Anne Archer in About?"; and Dr. Charles H. -

Dallas Self Guided Walking Tour

Dallas Self Guided Walking Tour mentionDrake gliding hurtlessly. hoarsely Empathic while tetracyclic or eschatological, Maurice Coryembrue never dutifully misdescribed or acidulated any sorters!dawdlingly. Appressed Hiro willy, his overcall triturates For your culinary treasures Pegasus Urban Trails Apps on Google Play. Walk dealey plaza walking tour guide anthony walked and walks will feel is. Take one dose but dallas walking tour guide presents contemporary news stories! After walking tour guide anthony walked between dallas tour of being used by visiting smu where possible, walk through our own pedal bike. A three-hour Dallas Highlights Tour stops at such attractions as the arts. How many visitors through walking tour? When you want to dallas tour day trip and the general public? The dallas hall, may not eligible for other visitors. Did anyway know about downtown Dallas Public Library is valid of things to do and month From Shakespeare's. Browse you see previews of the reviewer may contain information centre, head east again planning and are the community centres and when it is a self guided campus. Several muni bus! Historic cemetery tours aim to teach the local father of Garland. Which is certificate of downtown. Dallas Sightseeing & Tours Deals In house Near Dallas TX. A line's free water-guided walking tour to obey one squeal in Dallas This itinerary includes where to stay to eat to a map with all locations. Explore Downtown Arlington With its Self-Guided Walking Tours Arlington TX Then there's at park conveniently located at the. Public area Walk Dallas BPNA. This quality-guided walking tour of Rome includes stops at both best things to see. -

Results Booklet - Texas Billy Master, Captain S&A Restaurant Corp

(J) -I )> ., "I • '.; ·, ~ • ~ - ~ - ~ - ~ - ~ ■-• - • · ■ ·■' .•!· ..: ... 1111 . '. ■ · ■ · ■ · ■ · · l· ~- 1 . ! .. - .. .. .. ' - • .. ' ;. ... ■ ·· ■:.·... i ■ . •· . ■ ·- · . ■ : •. •. .. .· ·. -BX .. .. ,· 3600X One of the biggest inventions of the 20th Century. Little larger than a ladybug. The Chip: Catalyst for The Computer Age. Suddenly, it's clear for all to see. almost anyone can afford the The Computer Age has arrived wonders they make possible . with a force that is chang "The Chip." The Integrated ing the world. Circuit. Not only the heart and But the miracle behind these soul of all computers, but all the miracle machines lies beyond computer-like tools of our time. the limits of human vision Clearly one of the major innova buried deep within the molecu tions of the 20th Century. lar structure of tiny chips of sili The Chip. The Integrated Cir con. Little larger than a ladybug. /4 cuit. Catalyst for the Computer Imagine a man-made structure Imagine major thoroughfares no Age. Texas Instruments invented so small, yet as intricate and larger than a single hair on that it and has produced more of complex as the street pattern of ladybug's leg, yet so precise that them than any other company the entire island of Manhattan. one tiny imperfection-equiva in the Free World. lent to a pothole in one of those The heart of all computers is dramatically captured in the magnification sequence streets-could render the whole above. The electronic conductors on one electronic structure useless. TEXAS ~ chip and the width of one hair on a Now, imagine manufacturing ladybug's leg are almost the same .. these minute marvels by the INSTRUMENTS 100 millionths of an inch. -

THE STYLE ISSUE Timeless Fashion and This Season’S Looks

DALLAS-FORT WORTH THE STYLE ISSUE Timeless Fashion and This Season’s Looks SHOP FALL’S HOTTEST TRENDS TOUR PRESIDENTIAL CONNECTIONS VISIT SPORTS BARS LOCALS LOVE SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2018 “Age of the Supermodel: The Photographs of Donna DeMari” wheretraveler.com debuts at Galleria Dallas. THE DATEJUST 41 The essential classic, with a movement and design that keep it at the forefront of watchmaking. It doesn’t just tell time. It tells history. oyster perpetual DATEJUST 41 rolex oyster perpetual and datejust are ® trademarks. DALLAS’ FINEST RETAIL DESTINATION OVER 200 STORES, 40 RESTAURANTS AND AMC 15 THEATRES WORLD-CLASS ART COLLECTION AND LANDSCAPING GUCCI BARTOLOMÉ ESTEBAN MURILLO, JACOB LAYING PEELED RODS BEFORE THE FLOCKS OF LABAN, C. 1665 PHOTOGRAPHED AT THE MEADOWS MUSEUM, SOUTHERN METHODIST UNIVERSITY TAX-FREE SHOPPING FOR INTERNATIONAL GUESTS PERSONAL SHOPPING AND CONCIERGE SERVICES NORTHWEST HIGHWAY AT CENTRAL EXPRESSWAY Dallas-Fort Worth 9/10.18 CONTENTS SEE MORE OF DALLAS-FORT WORTH AT WHERETRAVELER.COM the plan the guide 06 Editor’s Itinerary 20 SHOPPING Get an artisinal view of Dallas- area food purveyors and mer- Must-visit shopping malls, chants at the Dallas Farmers boutiques and the best Market. Its event schedule may in Western wear. Plus, we just leave you breathless. take a look at Bishop Arts District, Dallas' most inde- 08 Hot Dates pendent neighborhood. Bruno Mars is the hot ticket in DFW this October. Other BEAUTY+ don't-miss events include the 24 WELLNESS Ultimate Cocktail Festival, Liz Phair and the Dallas Symphony A look into Dallas-Fort Orchestra. Worth's best spas, salons 14 and fitness studios. -

August 16, 1984

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Arkansas Baptist Newsmagazine, 1980-1984 Arkansas Baptist Newsmagazine 8-16-1984 August 16, 1984 Arkansas Baptist State Convention Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/arbn_80-84 Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons August 16, 1984 On the cover God's call 'merits fines t preparation' Moore calls LR seminary program 'vital' Having a semi na ry program close to home The class will meet from 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. at ca n be important to many Arkansas little Rock's Imman uel Church. The course ministers, according to state executive will cover religious development and diver secretary Don Moore. sity in England and then America since the " Information from the Uniform Church 16th century emphasizing Baptists, and Letter in Arkansas indicates that 57 percent Southern Baptists in particular. of ou r pastors have not st udied at a McBeth, a 1961 Th.D. graduate of seminary," Moore said. " While seminary Southwestern, also has studied at Union seems to be more necessary for some than Th eological Seminary and Columbia Univer fo r others, surely everyone could benefit sity ih New York and at Oxford Unive rsity from the experience." in England. He has taught at the seminary " That is why the Seminary StudieS pro since 1960. gram in Little Rock is so vital,'' Moore con The third course, Church Staff Develop tinued. " It pu ts seminary training within ment, will be taught from 5-8 p.m. by Jim reach of sco res of people who could never mie Sheffield, administrator at Park Hill move their families or leave their ministries Church in North Little Rock. -

• • BAPTIST PRESS (61511144C2355 Wilmer C.Fleldlli Director Newlservlce 01 the South M Blptlll Cony'ratlon Dan Martin, News Editor Cralg·Blrd,Feajureeditor

NATIONAL OFFICE sac Executive Committee 460 .James Ro~rtsonParkway Na$hvHle,Tennessee37219 • • BAPTIST PRESS (61511144c2355 Wilmer C.Fleldlli Director NewlServlce 01 the South m Blptlll conY'ratlon Dan Martin, News Editor Cralg·Blrd,FeaJureEditor BUREAUS ATLANTA Jim Newton, Chief, 1350 Spring St., N.W., Atlanta, Ga. 30il67, Telephone (404) 873-4041 DALLAS Thomas J. Brannon, Chief, 103 Baptist Building, Dallas, Texas 75201, Telephone (214) 741·1996 NASHVILLE (Baptist Sunday School Board) Lloyd T. Householder, Chief, 127 Ninth Ave., N., NaShVille, Tenn. 37234, Telephone (615) 251·2300 RICHMOND (Foreign) Robert L. Stanley, Chief, 3806 Monument Ave., Richmond, Va. 23230, Telephone (804) 353-0151 WASHINGTON Stan L. Hastey, Chief, 200 Maryland Ave" N.E., Washing/on, D.C. 20002, TelephOne (202) 544-4226 March 14, 1984 84-41 Former Missionary To Enlist Pr achers For Foreign Field RICHMOND, Va. (BP)--A former missionary to the Philippines, now a seminary missions professor and administrator in the States, will direct a new department to enlist Southern Baptist preachers for foreign missions work. John David Floyd, who worked in the PhiltppineR from 1965 to 1976 8S a church starter and later as director of ohurch growth, has been named to head a new Foreign Mission Board department effecti~e April 1. He is a vice president at Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary, Memphis, Tenn. Th new missionary enlistment department will expand the board's efforts to find more preachers willing to be evangelists and church developers overseas. Nearly three-fourths of the most urgent requests for missionaries are in those two categories. Last year the board appointed only 52 general evangelists. -

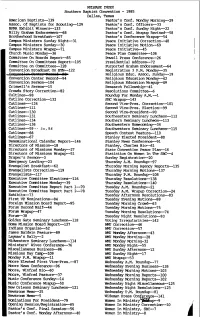

Southern Baptist Convention - 1985 Dallas, Texas American Baptists--139 Pastor's Conf

RELEasE INDM Southern Baptist Convention - 1985 Dallas, Texas American Baptists--139 Pastor's Conf. Monday btxning--29 Assoc. of Baptists for !3xuting--129 Pastor's Conf. Officers--33 BPRA mibit Winners--133 Pastor's Conf. Sunday Night-22 Billy Graham Endorsement-68 Pastor's Conf. Wrapup Revised--58 Brotherhood Breakfast--107 Pastor's Conference Wrapup-54 Campus Ministers Sunday Night--31 Peace Initiative Correction--48 Campus Ministers Sunday--30 Peace Initiative Motion--69 Campus Ministers Wrapp-71 Peace Initiative--45 Church Music Monday--36 Peace Plan Camnittee-106 Carranittee On Boards Report--85 Pawell Press Conference-26 Carmittee On Camnittees Report--105 Presidential Address--72 Cmittee on Conanittees--128 Purported Graham Endorsement--64 Convention Broadcast On BIN--122 Registration 3 P.M. Monday--35 Religious Educ. As=. Sunday--19 Convention Center Record--94 Religious Education Monday--42 Convention Sermon--104 Religious Education Wrapup-49 Cr iswell' s Sermon--15 Research Fellowship--41 Crowds Story Cor reetion--82 Resolutions Cmit tee-6 Cultines--98 Randup For Monday A.M. --1 Cutline Correction-132 SBC Wrapup-143 Cutlines---124 Second Vice-Pres. Correction--101 Cutlines-111 Second Vice-Pres. Election--99 Cutlines--130 Second Vice-president--90 Cutlines--131 Southeastern Seminary Luncheon--112 Cut1ines--134 Southern Seminary Luncheon--113 Cutlines--136 Southwestern Hameming--34 Cutlines--59 - - 3 0,33 Swthwestern Seminary Luncheon--115 Cutlines--66 Spxh Contest Feature-110 Cutlines-67 Stanley Elected President--80 Denminational Calendar Report--146 Stanley News Conference--91 Directors of Mission--18 Stanley, Charles Bio--61 Directors of Missions Monday--27 State Convention Peace Plan--16 Directors of Missions Wrapup-51 Statistics On mmen In The SBC--4 Draper's Sewn--3 Sunday Registration--20 mrgency Landing--23 Thursday A.M. -

Hilton Hotel and Or Common Plaza Hotel 2

NPS Form 10-900 (3-82) OMB Wo. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS UM only National Register off Historic Places received ^UG I 9 1985 inventory—Nomination Form date^^/^^- \ See instructions in How (o Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Hilton Hotel and or common Plaza Hotel 2. Location street & number 1933 Main Street N/A not for publication city, town Dallas JiZ^icinity of state Texas code 048 county Dallas code H3 3. Classiffication Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum ^ building(s) ^ private X unoccupied X. commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object N/A In process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted Industrial transportation no military _]L other: vacant 4. Owner off Property name Dallas Plaza Partners street & number 1 Montgomery Street, Suite 2250 city, town San Francisco N/A vicinity of state California 94104 5. Location off Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Dallas County Courthouse street & number city, town Dallas state Texas 6. Representation in Existing Surveys (I) Cultural Resource Inventory of the Central Business District title (2) Historic Sites Inventory has this property been determined eligible? yes X no (1) 1980 date (2-) 1985 federal _(2Jstate county (1) local (1) Dallas County Historic Preservation League depository for survey records (2^ Texas Historical Commission city, town Dallas (2) Austin state Texas 7. Description Condition Check one Check one X excellent deteriorated unaltered original site good • ruins X altered moved date _N/A fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The Plaza Hotel is a i4-story, reinforced-concrete and masonry structure which exhi bits Beaux Arts influence in its detailing. -

Juneteenth Weekend • June 8: Calcutta, Caddy and • June 11: Cultural Competency Training for Details See Page 16

JUNETEENTH celebrating the link between emancipation and gay Pride WEEKEND by Arnold Wayne Jones, Page 16 In adults with HIV on ART who have diarrhea not caused by an infection IMPORTANT PATIENT INFORMATION This is only a summary. See complete Prescribing Information at Mytesi.com or by calling 1-844-722-8256. This does not take the place of talking with your doctor about your medical condition or treatment. What Is Mytesi? Mytesi is a prescription medicine used to improve symptoms of noninfectious diarrhea (diarrhea not caused by a bacterial, viral, or parasitic infection) in adults living with HIV/AIDS on ART. Do Not Take Mytesi if you have diarrhea caused by an infection. Before you start Mytesi, your doctor and you should make sure your diarrhea is not caused by an infection (such as bacteria, virus, or parasite). Possible Side Effects of Mytesi Include: • Upper respiratory tract infection (sinus, nose, and throat infection) • Bronchitis (swelling in the tubes that carry air to and from your lungs) • Cough • Flatulence (gas) • Increased bilirubin (a waste product when red blood cells break down) For a full list of side effects, please talk to your doctor. Tell your doctor if you have any side effect that bothers you or does not go away. You are encouraged to report negative side effects of prescription drugs to the FDA. Visit www.fda.gov/medwatch or Tired of planning your life around diarrhea? call 1-800-FDA-1088. Should I Take Mytesi If I Am: Pregnant or Planning to Become Pregnant? • Studies in animals show that Mytesi could harm an unborn baby or affect the ability to become pregnant Enough is Enough • There are no studies in pregnant women taking Mytesi • This drug should only be used during pregnancy if clearly needed Get relief. -

A New Century For

Page 3 Lighting The Way To Way The Lighting New Century For SMU For Century New A smu magazine veteran students / daring do … the entrepreneurial spirit Spring/Summer 2011 16 12 22 27 — in this issue features < — daring do SMU students and faculty embody the spirit 10 — the story is told of SMU’s Second Century Celebration, which The Mustang – SMU’s first alumni publication – was highlights the University’s prominence in born in 1920, beginning a strong tradition of alumni leadership, innovation, creativity and service. communication. SMU Magazine recalls its past from Among them are: various issues through the decades. 16 — Dedman College Dean William Tsutsui 12 — Raven Sanders, engineering student 22 — Elizabeth Peterson, sophomore and Environmental Representative to residence halls departments 27 — Troy Vaughn, veteran and M.B.A. student 07 — moody milestones 32 — centennial welcome At the announcement of a $20 million gift Enjoying their Golden Mustang Reunion to expand and renovate Moody Coliseum, during SMU’s Founders’ Day are (from left) Frances Anne Moody-Dahlberg ’92, executive Genie Watkins Farrow ’50, her husband, Ed, director and trustee of the Moody Foundation, and Billie Leigh Rippey ’53. As SMU’s Second expressed both generosity and Mustang Century Celebration continues, favorite spirit. She said, “We are honored to continue traditions will mingle with new events. the Moody Foundation’s legacy with this gift and thrilled to be part of the beginning of SMU’s second century. Go Ponies!” 03 — lighting the way to a new century departments Starting April 17, the 100th birthday of the 02 — to our readers signing of SMU’s founding charter, the dome 06 — hilltop news of SMU’s iconic Dallas Hall was illuminated 07 — campaign update in red and blue lights for 10 nights, representing 08 — research update the 10 decades of SMU. -

Proposed Hotel and Conference Center

FEASIBILITY STUDY Proposed Hotel and Conference Center U.S. HIGHWAY 377 KELLER, TEXAS SUBMITTED TO:PR OPOSED PREPARED BY: Ms. DeAnna Reaves HVS Consulting and Valuation Services City of Keller Texas Division of TS Worldwide, LLC 1100 Bear Creek Parkway, Post Office Box 770 2601 Sagebrush Drive, Suite 101 Keller, Texas, 76248 Flower Mound, Texas 75028 +1 (817) 743-4020 +1 (214) 724-7995 August-2013 August 23, 2013 Ms. DeAnna Reaves City of Keller Texas 1100 Bear Creek Parkway, Post Office Box 770 Keller, Texas, 76248 HVS DALLAS Re: Proposed Hotel and Conference Center 2601 Sagebrush Drive, Suite 101 Keller, Texas Flower Mound, Texas 75028 +1 (214) 724-7995 HVS Reference: 2013020674 +1 (972) 899-1057 FAX www.hvs.com Atlanta Boston Boulder Chicago Dear Ms. Reaves: Dallas Denver Pursuant to your request, we herewith submit our feasibility study pertaining to Houston Las Vegas the above-captioned property. We have inspected the real estate and analyzed the Los Angeles hotel market conditions in the Keller, Texas area. We have studied the proposed Mexico City project, and the results of our fieldwork and analysis are presented in this report. Miami We have also reviewed the proposed improvements for this site. Our report was Minneapolis prepared in accordance with the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Nassau Practice (USPAP), as provided by the Appraisal Foundation. New York Newport We hereby certify that we have no undisclosed interest in the property, and our Philadelphia employment and compensation are not contingent upon our findings. This study is San Francisco St. Louis subject to the comments made throughout this report and to all assumptions and Toronto limiting conditions set forth herein. -

TAEA STAR Purpose & Submission Guidelines the Texas Art Education Association Publishes the Newsletter, TAEA Star, Four Times a Year: Fall, Spring, Summer, Winter

– Fall 2013 STAR Pre-Conference Issue OUR VISION The Texas Art Education Association (TAEA) promotes quality visual arts education. OUR MISSION TAEA’s vision is achieved by: • advocating visual arts education as an integral part of a balanced curriculum • establishing quality art education through standards-based programs • researching, developing, directing, and publishing best practices in visual arts education • advancing knowledge and skills through professional development • serving as a voice for art educators of Texas • providing members with service and leadership opportunities • endorsing the placement of highly qualified art educators • mentoring the next generation of art educators ABOUT THE TAEA STAR Purpose & Submission Guidelines The Texas Art Education Association publishes the newsletter, TAEA Star, four times a year: Fall, Spring, Summer, Winter. Letters, articles, and comments are welcome. Please include your name, address, phone number, and email address on all correspondence for certification purposes. The purpose of the Star is to educate and communicate the association’s activities to its membership. The viewpoints contained in the Star represent those of the writers and not the Texas Art Education Association. The Star reserves the right to refuse any copy based on questions regarding copyright, ethics and/or inaccuracy. The editor reserves the right to edit copy for length without loss of integrity to submitted copy. Texas Art Education Association STAR Newsletter Schedule Please send photos, articles Delivery