Indecon International Consultants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Survey of Native Woodlands 2003-2008 Volume I - BEC Consultants Ltd

NationalNational SurveySurvey ofof NativeNative WoodlandsWoodlands 20032003 --20082008 Volume I: Main report Philip Perrin, James Martin, Simon Barron, Fionnuala O’Neill, Kate McNutt & Aoife Delaney Botanical, Environmental & Conservation Consultants Ltd. 2008 A report submitted to the National Parks & Wildlife Service Executive Summary The National Survey of Native Woodlands in Ireland included the survey of 1,217 woodland sites across all 26 counties of the Republic of Ireland during 2003-2007. Site selection was carried out using the Forest Inventory Planning System 1998 (FIPS) and local knowledge. Surveys comprised the recording of site species lists and information at the site level on topography, management, grazing, natural regeneration, geographical situation, adjacent habitat types, invasive species, dead wood and boundaries. Relevés were recorded in each of the main stand types identified at each site. For each relevé, data were recorded on vascular plant and bryophyte cover abundance, soil type and soil chemistry, notable lichens, stand structure, and natural regeneration. Data were also incorporated from a number of external sources. This resulted in a database with data from 1,320 sites and 1,667 relevés. The relevé dataset was analysed using hierarchical clustering and indicator species analysis. Four major woodland groups were defined: Quercus petraea – Luzula sylvatica (260 relevés), Fraxinus excelsior – Hedera helix (740 relevés), Alnus glutinosa – Filipendula ulmaria (296 relevés) and Betula pubescens – Molinia caerulea (371 relevés). Further analysis of the dataset divided these four groups into twenty-two vegetation types. For each vegetation type a synoptic table of the floristic data was produced, together with a list of key indicator species, a list of example sites, summary environmental and stand structure data and a distribution map. -

Irland 2014-Druck-Ii.Pdf

F. Higer: Nachlese der Pfarr-Reise 2014 auf die „Grüne Insel“ - - Inhalt 46 Connemara-Fotos 78 Land der Schafe 47 Lough Corrib 79 Killarney 3 Reiseprogramm 48 Croagh Patrick 80 Lady´s View 4 Irland 50 Westport 82 Adare 17 Irland - Geografie 51 Connemara 85 Rock of Cashel 21 Pale 52 Kylemore Abbey 89 Wicklow Montains 22 Röm.-kath. Kirche 56 Burren 91 Glendalough 24 Keltenkreuz 58 Polnabroune Dolmen 94 Dublin 25 Leprechaun / 60 Cliffs of Moher 100 St. Patrick´s Cathedral Rundturm 62 Limerick 103 Phoenix Park 26 Shamrock (Klee) 64 Augustiner / Limerick 104 Guinness Storehause 27 Flughafen Dublin 65 Tralee 106 St. Andrew´s Parish 28 Aer Lingus 66 Muckross Friary 107 Trinity College 31 Hotel Dublin 68 Muckross House 108 Trinity Bibliothek 32 Monasterboice 71 Star Seafood Ltd. 109 Book of Kells 34 Kilbeggan-Destillerie 72 Kenmare 111 Temple Bar 37 Clonmacnoise 73 Ring of Kerry 113 Sonderteil: Christ Church 41 Galway 75 Skellig Michael 115 Whiskey 43 Cong / Cong Abbey 77 Border Collie 118 Hl. Patrick & Hl. Kevin IRLAND-Reise der Pfar- Republik Irland - neben port, der Hl. Berg Irlands, Kerry", einer Hirtenhunde- ren Hain & Statzendorf: Dublin mit dem Book of der Croagh Patrick, Vorführung, Rock of diese führte von 24. März Kells in der Trinity- Kylemore Abbey, die Cashel, Glendalough am bis 1. April auf die "grüne Bücherei, der St. Patricks- Connemara, die Burren, Programm. Dank der guten Insel" Irland. Ohne auch nur Kathedrale und der Guin- Cliffs of Moher, Limerick, Führung, des guten Wetters einmal nass zu werden, be- ness-Brauerei, stand Monas- Muckross House und Friary und einer alles überragen- reiste die 27 Teilnehmer terboice, eine Whiskeybren- (Kloster), eine Räucherlachs den Heiterkeit war es eine umfassende Reisegruppe die nerei, Clonmacnoise, West- -Produktion, der "Ring of sehr gelungene Pfarr-Reise. -

Copyrighted Material

18_121726-bindex.qxp 4/17/09 2:59 PM Page 486 Index See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX Ardnagashel Estate, 171 Bank of Ireland The Ards Peninsula, 420 Dublin, 48–49 Abbey (Dublin), 74 Arigna Mining Experience, Galway, 271 Abbeyfield Equestrian and 305–306 Bantry, 227–229 Outdoor Activity Centre Armagh City, 391–394 Bantry House and Garden, 229 (Kildare), 106 Armagh Observatory, 394 Barna Golf Club, 272 Accommodations. See also Armagh Planetarium, 394 Barracka Books & CAZ Worker’s Accommodations Index Armagh’s Public Library, 391 Co-op (Cork City), 209–210 saving money on, 472–476 Ar mBréacha-The House of Beach Bar (Aughris), 333 Achill Archaeological Field Storytelling (Wexford), Beaghmore Stone Circles, 446 School, 323 128–129 The Beara Peninsula, 230–231 Achill Island, 320, 321–323 The arts, 8–9 Beara Way, 230 Adare, 255–256 Ashdoonan Falls, 351 Beech Hedge Maze, 94 Adrigole Arts, 231 Ashford Castle (Cong), 312–313 Belfast, 359–395 Aer Lingus, 15 Ashford House, 97 accommodations, 362–368 Agadhoe, 185 A Store is Born (Dublin), 72 active pursuits, 384 Aillwee Cave, 248 Athlone, 293–299 brief description of, 4 Aircoach, 16 Athlone Castle, 296 gay and lesbian scene, 390 Airfield Trust (Dublin), 62 Athy, 102–104 getting around, 362 Air travel, 461–468 Athy Heritage Centre, 104 history of, 360–361 Albert Memorial Clock Tower Atlantic Coast Holiday Homes layout of, 361 (Belfast), 377 (Westport), 314 nightlife, 386–390 Allihies, 230 Aughnanure Castle (near the other side of, 381–384 All That Glitters (Thomastown), -

Rootsmagic Document

First Generation 1. Geert Somsen1 was born about 1666 in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. He died about 1730 in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. He has a reference number of [P272]. (Boeinck), ook wel: Sumps. Geert werd op 24-06-1686 (Sint Jan) ingeschreven als lidmaat van de Nederduits Gereformeerde Gemeente Aalten [Boeinck (also: Sumps). Geert was admitted as a member of the Dutch Reformed Church of Aalten on 24-06-1686 (St. John)]. Geert Somsen and Mechtelt Gelkinck had marriage banns published on 28 Apr 1689 in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. They were married on 27 May 1689 in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. Mechtelt Gelkinck1 (daughter of Roelof Somsen and Geesken Rensen) was born before 25 Aug 1662 in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. 2 She was christened on 25 Aug 1662 in Dinxperlo, GE, Netherlands.2 She died in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. She has a reference number of [P273]. ook wel: Meghtelt. Also: Sumps. op 29-09-1688 werd Mechtelt als lidmaat v.d. Nederduits Geref. Ge,. Aalten ingeschreven [also: Meghtelt. Also: Sumps. On 29 Sep 1688 she was registered as Mechtelt as a member of the Dutch Reformed Church in Aalten]. Geert Somsen and Mechtelt Gelkinck had the following children: +2 i. Jantjen Somsen (born on 9 Nov 1690). +3 ii. Roelof Somsen (born about 1692). +4 iii. Geesken Somsen (born in 1695). +5 iv. Wander Somsen (born on 9 Jul 1699). +6 v. Frerik Somsen (born about Jan 1703). Second Generation 2. Jantjen Somsen1 (Geert-1) was born on 9 Nov 1690 in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. She died on 15 Sep 1767 in Dinxperlo, GE, Netherlands. -

TLP SPREE V 2.1 September 9 – 19, 2021

TLP SPREE V 2.1 September 9 – 19, 2021 JEM Tours 25 Washington Avenue Phone: 973-223-6553 Morris Plains, NJ 07950 Email: [email protected] 1 2 I TLP SPREE V 2.1 Itinerary Thu, Sep 9 UNITED STATES TO DUBLIN Enjoy an overnight flight across the Atlantic to Dublin. Fri, Sep 10 DUBLIN ARRIVAL, GIANTS CAUSEWAY & DERRY After landing at Dublin Airport you will meet your driver/guide who will welcome you to Ireland. After leaving the airport stop at a local restaurant, for a traditional Irish breakfast. Journey along through Ireland’s rolling hills and stop to visit the Giant’s Causeway, an impressive area of hexagonal columns formed over 60 million years ago by cooling lava which has given rise to many legends. Travel into the city of Derry and check into your hotel. This evening join your group for a walking tour along the city walls learning about its rich history. Cross the Peace Bridge and enjoy dinner at the Walled City Brewery. Sample some local brew as you dine with your fellow travelers. Hotel: Everglades Hotel, Derry Sat, Sep 11 GRIANAN OF AILEACH, BELLEEK CHINA Today, visit, the Grianan of Aileach which is one of Ireland's greatest circular ring forts. Archaeologists say that majority of the fort dates back to around 500 BC. Continue your journey and stop to visit the Belleek Pottery Factory to see how skilled craftspeople form and decorate clay to produce delicate porcelain masterpieces. Visit Drumcliffe Churchyard and view W.B. Yeats’ grave. Continue your journey to your hotel, check in and relax or freshen up before dinner at the hotel restaurant with your fellow travelers. -

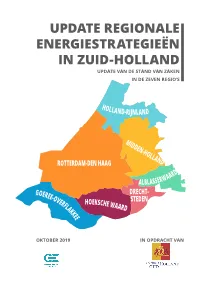

PZH Evaluatie Update RES Rapport

UPDATE REGIONALE IN DE ZEVEN REGIO’S UPDATE VAN DE STAND VAN ZAKEN ENERGIESTRATEGIEËNIN ZUID-HOLLANDD LAN RIJN ND- HOLLA MIDDEN-HOLLAND D R AA W ER SS LA ALB DRECHT- STEDEN ROTTERDAM-DEN HAAG RD E WAA KSCH HOE IN OPDRACHT VAN EREE-OVERFLAK GO KEE OKTOBER 2019 2 1| INLEIDING INLEIDING Dit document is een update van de studie ‘Regionale Energiestrategieeën in Zuid-Holland, analyse en vergelijking van de stand van zaken in de zeven regio’s’, uit augustus 2018. Deze update kijkt dus naar de huidige stand van zaken, in oktober 2019. De provincie Zuid-Holland bestaat uit 7 RES-regio’s; Alblasserwaard, Drechtsteden, Goeree-Overflakkee, Hoeksche Waard, Holland-Rijnland, Midden-Holland, en Rotterdam-Den Haag. Voor de dikgedrukte vier regio’s zijn nieuwe documenten aangeleverd die in de update gebruikt zijn: - Alblasserwaard: BVR-eindrapport (conceptversie) - Alblasserwaard: Res vervolgproces_alblasserwaard - Drechtsteden: transitievisie warmte 1.0 - Holland-Rijnland : Energieakkoord Holland Rijnland 2017-2025, Uitvoeringsprogramma 2019 - Holland-Rijnland: Notitie ‘Van Regionaal Energieakkoord Holland Rijnland naar Regionale Energiestrategie (RES) Holland Rijnland’ - Rotterdam-Den Haag: Energieperspectief 2050 Rotterdam-Den Haag - Rotterdam-Den Haag: Regionale prioriteiten RES De gebruikte bronnen van het rapport van augustus 2018 staan genoemd ‘Regionale Energiestrategieeën in Zuid-Holland, analyse en vergelijking van de stand van zaken in de zeven regio’s’, uit augustus 2018. In deze update is de nadruk gelegd op de regio Rotterdam-Den Haag, Alblasserwaard, Drechtsteden en Holland- Rijnland omdat er voor deze deelregio’s nieuwe documenten ontwikkeld zijn. Voor de overige regio’s zijn er in dit overzichtsdocument geen aanpassingen gedaan. Wel zijn de aangepaste grenzen van de deelregio’s en van de provincie aangepast naar 2019. -

Ireland P a R T O N E

DRAFT M a r c h 2 0 1 4 REMARKABLE P L A C E S I N IRELAND P A R T O N E Must-see sites you may recognize... paired with lesser-known destinations you will want to visit by COREY TARATUTA host of the Irish Fireside Podcast Thanks for downloading! I hope you enjoy PART ONE of this digital journey around Ireland. Each page begins with one of the Emerald Isle’s most popular destinations which is then followed by several of my favorite, often-missed sites around the country. May it inspire your travels. Links to additional information are scattered throughout this book, look for BOLD text. www.IrishFireside.com Find out more about the © copyright Corey Taratuta 2014 photographers featured in this book on the photo credit page. You are welcome to share and give away this e-book. However, it may not be altered in any way. A very special thanks to all the friends, photographers, and members of the Irish Fireside community who helped make this e-book possible. All the information in this book is based on my personal experience or recommendations from people I trust. Through the years, some destinations in this book may have provided media discounts; however, this was not a factor in selecting content. Every effort has been made to provide accurate information; if you find details in need of updating, please email [email protected]. Places featured in PART ONE MAMORE GAP DUNLUCE GIANTS CAUSEWAY CASTLE INISHOWEN PENINSULA THE HOLESTONE DOWNPATRICK HEAD PARKES CASTLE CÉIDE FIELDS KILNASAGGART INSCRIBED STONE ACHILL ISLAND RATHCROGHAN SEVEN -

Architectural Conservation Areas

A3 Architectural Conservation Areas 415 A3 Architectural Conservation Areas ARDBRACCAN DEMESNE ACA Historical Development Ardbraccan House and demesne occupy an historically important site as it has been the seat of the Bishops of Meath since the fourteenth century. The house is set in mature pasture land with formal and walled gardens. The construction of the house commenced c. 1734 to the designs of Richard Castle and was completed in the 1770’s to the designs of James Wyatt, Thomas Cooley and the Rev. Daniel Beaufort. Built Form The domestic and agricultural outbuildings associated with Ardbraccan House display an exceptionally high level of architectural design. These include piggeries, granary, dovecotes, bell tower, bullock sheds, carriage house, fowl yards, laundry yard, pump yard, slaughter house, vaulted stables, and clock tower. The Demesne structures include the gate lodges, entrance gates and walls, ha-ha, eel pond, ice house, vineries, grotto, and water pump. The detached two-storey four-bay house, possibly the farm manager’s house, was built c.1820, of randomly coursed limestone with roughcast render and raised rendered quoins. The particular interest of this building is in its relationship with the single-storey cottages to the immediate north. Within the demesne are other structures – St Ultan’s Church and graveyard, Infant school, dated 1856, and holy well. Objectives 1. To preserve the character of the demesne, its designed landscape and built features by limiting the extent of new development permitted within the demesne and requiring that any such development respect the setting and special qualities of the demesne. 2. To require that all works, whether of maintenance and repair, additions or alterations to existing buildings or built features within the demesne shall protect the character of those buildings and features by the use of appropriate materials and workmanship. -

CSG Bibliog 24

CASTLE STUDIES: RECENT PUBLICATIONS – 29 (2016) By Dr Gillian Scott with the assistance of Dr John R. Kenyon Introduction Hello and welcome to the latest edition of the CSG annual bibliography, this year containing over 150 references to keep us all busy. I must apologise for the delay in getting the bibliography to members. This volume covers publications up to mid- August of this year and is for the most part written as if to be published last year. Next year’s bibliography (No.30 2017) is already up and running. I seem to have come across several papers this year that could be viewed as on the periphery of our area of interest. For example the papers in the latest Ulster Journal of Archaeology on the forts of the Nine Years War, the various papers in the special edition of Architectural Heritage and Eric Johnson’s paper on moated sites in Medieval Archaeology. I have listed most of these even if inclusion stretches the definition of ‘Castle’ somewhat. It’s a hard thing to define anyway and I’m sure most of you will be interested in these papers. I apologise if you find my decisions regarding inclusion and non-inclusion a bit haphazard, particularly when it comes to the 17th century and so-called ‘Palace’ and ‘Fort’ sites. If these are your particular area of interest you might think that I have missed some items. If so, do let me know. In a similar vein I was contacted this year by Bruce Coplestone-Crow regarding several of his papers over the last few years that haven’t been included in the bibliography. -

MUNSTER VALES STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN November 2020

Strategic Tourism Development Plan 2020-2025 Developing the TOURISM POTENTIAL of the Munster Vales munster vales 2 munster vales 3 Strategic Tourism Development Plan Strategic Tourism Development Plan CONTENTS Executive Summary Introduction 1 Destination Context 5 Consultation Summary 19 Case Studies 29 Economic Assessment 39 Strategic Issues Summary 49 Vision, Recommendations and Action Plan 55 Appendicies 85 Munster Vales acknowledge the funding received from Tipperary Local Community Development Committee and the EU under the Rural Development Programme 2014- 2020. “The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development: Europe investing in rural areas.” Prepared by: munster vales 4 munster vales 5 Strategic Tourism Development Plan Strategic Tourism Development Plan MUNSTER VALES STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN November 2020 Prepared by: KPMG Future Analytics and Lorraine Grainger Design by: KPMG Future Analytics munster vales i munster vales ii Strategic Tourism Development Plan Strategic Tourism Development Plan The context for this strategy is discussed in Part Two. To further raise the profile of Munster Vales, enhance the This includes an overview of progress which highlights the cohesiveness of the destination, and to maximise the opportunity following achievements since the launch of Munster Vales in presented by four local authorities working in partnership, this 2017: strategy was tasked with identifying a small number of ambitious products that could be developed and led by Munster Vales ■ Acted as an umbrella destination brand -

Sustainable Management of Tourist Attractions in Ireland: the Development of a Generic Sustainable Management Checklist

SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF TOURIST ATTRACTIONS IN IRELAND: THE DEVELOPMENT OF A GENERIC SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT CHECKLIST By Caroline Gildea Supervised by Dr. James Hanrahan A dissertation submitted to the School of Business and Humanities, Institute of Technology, Sligo in fulfilment of the requirements of a Master of Arts (Research) June 2012 1 Declaration Declaration of ownership: I declare that this thesis is all my own work and that all sources used have been acknowledged. Signed: Date: 2 Abstract This thesis centres on the analysis of the sustainable management of visitor attractions in Ireland and the development of a tool to aid attraction managers to becoming sustainable tourism businesses. Attractions can be the focal point of a destination and it is important that they are sustainably managed to maintain future business. Fáilte Ireland has written an overview of the attractions sector in Ireland and discussed how they would drive best practice in the sector. However, there have still not been any sustainable management guidelines from Fáilte Ireland for tourist attractions in Ireland. The principal aims of this research was to assess tourism attractions in terms of water, energy, waste/recycling, monitoring, training, transportation, biodiversity, social/cultural sustainable management and economic sustainable management. A sustainable management checklist was then developed to aid attraction managers to sustainability within their attractions, thus saving money and the environment. Findings from this research concluded that tourism attractions in Ireland are not sustainably managed and there are no guidelines, training or funding in place to support these attraction managers in the transition to sustainability. Managers of attractions are not aware or knowledgeable enough in the area of sustainability. -

Carloviana Index 1947 - 2016

CARLOVIANA INDEX 1947 - 2016 Abban, Saint, Parish of Killabban (Byrne) 1986.49 Abbey, Michael, Carlow remembers Michael O’Hanrahan 2006.5–6 Abbey Theatre 1962.11, 1962.38 Abraham Brownrigg, Carlovian and eminent churchman (Murphy) 1996.47–48 Academy, College Street, 1959.8 (illus.) Across the (Barrow) river and into the desert (Lynch) 1997.10–12 Act of Union 2011.38, 2011.46, 2012.14 Act of Union (Murphy) 2001.52–58 Acton, Sir John, M.P. (b. 1802) 1951.167–171 actors D’Alton, Annie 2007.11 Nic Shiubhlaigh, Máire 1962.10–11, 1962.38–39 Vousden, Val 1953.8–9, 1983.7 Adelaide Memorial Church of Christ the Redeemer (McGregor) 2005.6–10 Administration from Carlow Castle in the thirteenth century (O’Shea) 2013–14.47-48 Administrative County Boundaries (O’Shea) 1999.38–39, 1999.46 Advertising in the 1850’s (Bergin) 1954.38–39 advertising, 1954.38-39, 1959.17, 1962.3, 2001.41 (illus.) Advertising for a wife 1958.10 Aedh, Saint 1949.117 Aerial photography a window into the past (Condit & Gibbons) 1987.6–7 Agar, Charles, Protestant Archbishop of Dublin 2011.47 Agassiz, Jean L.R. 2011.125 Agha ruins 1982.14 (illus.) 1993.17 (illus.) Aghade 1973.26 (illus.), 1982.49 (illus.) 2009.22 Holed stone of Aghade (Hunt) 1971.31–32 Aghowle (Fitzmaurice) 1970.12 agriculture Carlow mart (Murphy) 1978.10–11 in eighteenth century (Duggan) 1975.19–21 in eighteenth century (Monahan) 1982.35–40 farm account book (Moran) 2007.35–44 farm labourers 2000.58–59, 2007.32–34 harvesting 2000.80 horse carts (Ryan) 2008.73–74 inventory of goods 2007.16 and Irish National League