The Renewable Energy Research, Development and Demonstration Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notice Concerning Copyright Restrictions

NOTICE CONCERNING COPYRIGHT RESTRICTIONS This document may contain copyrighted materials. These materials have been made available for use in research, teaching, and private study, but may not be used for any commercial purpose. Users may not otherwise copy, reproduce, retransmit, distribute, publish, commercially exploit or otherwise transfer any material. The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specific conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be "used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research." If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. HOT DRY ROCK - A EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE J.D. Garnish Energy Technology Support Unit AERE Harwell, Oxon, England ABSTRACT permeability but natural hydrothermal circulation in existing fractures. For the purposes of this review HDR Research into hot dry rock technology is being pursued research is defined narrowly as work directed towards the actively in several European countries. All these projects creation of a heat transfer zone in otherwise impermeable employ variations of the basic hydrofracturing approach. rock, and the extraction of useful heat by the circulation of Following proof of the concept at Los Alamos, the UK fluid through that zone. -

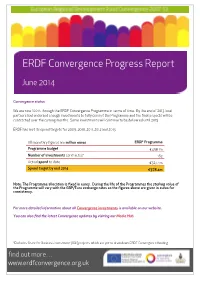

ERDF Convergence Progress Report, Jun 2014 DRAFT.Pub

ERDF Convergence Progress Report June 2014 Convergence status We are now 100% through the ERDF Convergence Programme in terms of time. By the end of 2013 local partners had endorsed enough investments to fully commit the Programme and the final projects will be contracted over the coming months. Some investments will continue to be delivered until 2015. ERDF has met its spend targets for 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2013. All monetary figures are million euros ERDF Programme Programme budget €458.1m Number of investments contracted* 163 Actual spend to date €327.4m Spend target by end 2014 €378.4m Note: The Programme allocation is fixed in euros. During the life of the Programmes the sterling value of the Programme will vary with the GBP/Euro exchange rates so the figures above are given in euros for consistency. For more detailed information about all Convergence investments is available on our website. You can also find the latest Convergence updates by visiting our Media Hub. *Excludes Grant for Business Investment (GBI) projects which are yet to draw down ERDF Convergence funding. find out more… www.erdfconvergence.org.uk CONVERGENCE INVESTMENTS New Investments Apple Aviation Ltd Apple Aviation, an aircraft maintenance, repair and overhaul company, has established a base at Newquay Airport’s Aerohub. Convergence funding from the Grant for Business Investment programme will contribute to salary costs for thirteen new jobs in the business. ERDF Convergence investment: £211,641 (through the GBI SIF) Green Build Hub Located alongside the Eden Project, the Green Build Hub will be a research facility capable of demonstrating and testing the performance of innovative sustainable construction techniques and materials in a real building setting. -

United Downs Deep Geothermal Power Project, UK. Project Update

PROCEEDINGS, 44th Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering Stanford University, Stanford, California, February 11-13, 2019 SGP-TR-214 The United Downs Deep Geothermal Power Project Peter Ledingham, Lucy Cotton and Ryan Law Geothermal Engineering Ltd, Falmouth Business Park, Bickland Water Road, Falmouth, Cornwall TR11 4SZ, UK [email protected] Keywords: United Downs, Cornwall, UK, Deep Geothermal, ABSTRACT The United Downs Deep Geothermal Power project is the first geothermal power project in the United Kingdom. It is located near Redruth in west Cornwall, UK and is part-funded by the European Regional Development Fund and Cornwall Council. The project consists of two deviated wells; a production well to a target depth of 4,500m and an injection well to a depth of 2,500m. Both wells target a sub-vertical, inactive fault structure that is thought will provide enhanced permeability relative to the surrounding granitic rock, sufficient to support circulation of between 20 and 60l/s. Geothermal gradients in Cornwall are relatively good and the bottom hole temperature is expected to be in the region of 190OC, allowing anticipated production to surface at greater than 175OC, which should allow electricity generation of between 1 and 3WMe. After funding agreements were signed in June 2017, a period of preparation and procurement followed, and drilling began in November 2018. This paper places the project in the context of previous geothermal research carried out in Cornwall, summarises the concept and describes the site selection work carried out. It also outlines the microseismic and noise monitoring programmes implemented to protect the local community and describes the public outreach, education and research initiatives associated with the project. -

Cornwall & Isles of Scilly Strategic Economic Plan

Cornwall & Isles of Scilly Strategic Economic Plan Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly: Geographically and culturally distinct, respected as a unique blend of ‘people and place’ where the environment is valued both as a business asset and an inspiration for life. We live on the edge and thrive there. We’re a place where ideas are nurtured and have the opportunity to flourish. 2 Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Strategic Economic Plan 1 Foreword NEXT GENERATION PIONEERS – creating our future economy today Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly are at the very and our marine energy programme is supported edge of Britain; our rural location has created a by expertise from Exeter University, Plymouth place for new ways of thinking, new adventures University and via the Plymouth and Peninsula City and discoveries often keeping us ahead of the Deal. Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly also form part market. In today’s world this has enabled digital of the South West Marine Energy Park which builds inclusion, different ways of working and the on a blend of offshore renewable energy resource, initiation of different business models. economic, technical and industrial expertise. Finally, Great ideas take hold quickly here and we provide a Cornwall’s geology also makes it an ideal location for fertile environment for piloting new thinking. deep geothermal energy. Cornwall is the first region We possess the environmental advantages of in the UK to approve planning permission for deep being an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty – the geothermal plants. largest in the UK covering a third of the land mass Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly have the necessary and encompassing a World Heritage site and an pre-requisites to be world leaders in the development archipelago 28 miles off the mainland. -

CHAPTER 4 – Review of EGS and Related Technology – Status and Achievements

CHAPTER 4 Review of EGS and Related Technology – Status and Achievements 4.1 Scope and Organization _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _43 4.2 Overview _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _43 4.3 Fenton Hill _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _47 4.3.1 Project history _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _47 4.3.2 Lessons learned at Fenton Hill _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _412 41 4.4 Rosemanowes _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _414 4.4.1 Project history _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _414 4.4.2 Lessons learned at Rosemanowes _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _417 4.5 Hijiori _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _419 4.5.1 Project history _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _419 4.5.2 Lessons learned at Hijiori _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _423 4.6 Ogachi _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _424 4.6.1 Project history _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _424 4.6.2 Lessons learned at Ogachi _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _426 4.7 Soultz _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _426 4.7.1 Project history _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ -

Baseline Report Series: 16. the Granites of South-West England

Baseline Report Series: 16. The Granites of South-West England Groundwater Systems and Water Quality Commissioned Report CR/04/255 Environment Agency Science Group Technical Report NC/99/74/16 The Natural Quality of Groundwater in England and Wales A joint programme of research by the British Geological Survey and the Environment Agency BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Commissioned Report CR/04/255 ENVIRONMENT AGENCY Science Group: Air, Land & Water Technical Report NC/99/74/16 This report is the result of a study jointly funded by the British Geological Baseline Report Series: Survey’s National Groundwater Survey and the Environment Agency’s Science 16. The Granites of South-West Group. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or England by any means, or stored in a retrieval system of any nature, without the prior permission of the copyright proprietors. All rights are reserved by the copyright P L Smedley and D Allen proprietors. Disclaimer Contributors The officers, servants or agents of both the British Geological Survey and the Environment Agency accept no liability *M Thornley, R Hargreaves, C J Milne whatsoever for loss or damage arising from the interpretation or use of the information, or reliance on the views contained herein. Environment Agency Dissemination status *Environment Agency Internal: Release to Regions External: Public Domain ISBN: 978-1-84432-641-9 Product code: SCHO0207BLYN-E-P ©Environment Agency, 2004 Statement of use This document forms one of a series of reports describing the baseline chemistry of selected reference aquifers in England and Wales. Cover illustration Cliffs of jointed granite at Pordenack Point, near Land’s End (photography: C J Jeffery). -

GRC Bulletin January February 2019

GEOTHERMAL RESOURCES COUNCIL Vol. 48, No. 1 Bulletin January/February 2019 GRC Annual Meeting & Expo - 2018 -Geothermal’s Role in Today’s Energy Market Reducing the Costs of Geothermal Drilling RENEW YOUR MEMBERSHIP STAY connectedRENEW TODAY RENEWAL IS EASY! www.geothermal.org/membership.html STAY in TOUCH with GRC! Like us on Facebook: GRC and geothermal photos are posted www.facebook.com/ on Flicker: www.flicker.com/photos/ GeothermalResourcesCouncil geothermalresourcescouncil The Global Geothermal News is your GRC is on Pinterest: trusted source for geothermal news: www.pinterest.com/geothermalpower www.globalgeothermalnews.com Follow us on Twitter: @GRC2001 and #GRCAM2019 The online GRC Library offers thousands of technical GRC is on LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/in/ papers as downloadable PDF files. geothermalresourcescouncil www.geothermal-library.org Website: www.geothermal.org Phone: 530.758.2360 Email: [email protected] Fax: 530.758.2839 6 President’s Message by Andy Sabin Bulletin 8 Executive Director’s Message Vol. 48, No.1 by William Pettitt January/February 2019 10 Communication from the GRC by Ian Crawford 14 Inside Geothermal: North America, Central & South America, Australasia, Asia, Africa, Europe, Education, Science & Technology, Climate Change by Ian Crawford Geothermal Resources Council P.O. Box 1350 32 Geothermal History in the Making Davis, CA 95617-1350 - Hot Dry Rock Geothermal Energy Phone: 530-758-2360 Research at the Camborne School Fax: 530-758-2839 of Mines www.geothermal.org by Roger Parker Executive Director -

A Skills Action Plan for the Low Carbon Environmental Goods and Services Sector May 2014

2014 Tender Reference: TEN331 EVIDENCE BASE LOW CARBON ENVIRONMENTAL GOODS & SERVICES A Skills Action Plan for the Low Carbon Environmental Goods and Services Sector May 2014 Community Energy Plus 3-4 East Pool Tolvaddon Energy Park Camborne TR14 0HX Tel: 01209 614975 Web: www.cep.org.uk Study Authors: Dr Tim Jones (Chief Executive, Community Energy Plus), Dionne Jones (Funding and Development Manager, Community Energy Plus), Nicola McCheyne (Delivery Manager, Community Energy Plus), Ian Smith (CEP Associate/IS Consultancy), Nigel Tremlett (CEP Associate/Transform Research), Lucy Cornes (Communications Assistant, Community Energy Plus), Anthony Weight (CEP Associate). With the assistance of the Community Energy Plus team Published: March 2014 Produced for the Cornwall Development Company, Tender Reference TEN331 Lead contact for Cornwall Development Company: Nich Thomas, Business Skills Lead. Lead contact for Community Energy Plus: Dionne Jones, [email protected], 01209 614975 1 Community Energy Plus A Skills Action Plan for the Low Carbon Environmental Goods and Services Sector May 2014 CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ 11 2. Evidence Base Report A – LCEGS Sector Overview .................................................................................. 34 2.2.1. Defining the Low Carbon Environmental Goods and Services Sector ............................................ 35 2.2.2. Background and History ................................................................................................................. -

Deep Geothermal Review Study Final Report Department of Energy & Climate Change (DECC)

Deep Geothermal Review Study Final Report Department of Energy & Climate Change (DECC) October 2013 Deep Geothermal Review Study Final Report Notice This document and its contents have been prepared and are intended solely for the Department of Energy & Climate Change (DECC)’s information and use. Atkins Limited assumes no responsibility to any other party in respect of or arising out of or in connection with this document and/or its contents. Document history Job number: 5119440 Document ref: 5119440-RPT-004 Revision Purpose description Originated Checked Reviewed Authorised Date Rev 1.0 DRAFT Report AN/IR PT/NK/OM DS/NA 05/07/13 Rev 2.0 Final Report AN/IR PT/OM DS/NA 31/08/13 Rev 3.0 Re-drafted Final Report DP IR/MH DS DP 27/09/13 Rev 4.0 Re-drafted Final Report DP IR/MH DS DP 18/10/13 Rev 5.0 Corrected Final Report DP IR/MH DS DP 21/10/13 Atkins Deep Geothermal Review Study | Version 5.0 | 21 October 2013 Deep Geothermal Review Study Final Report Table of contents Chapter Pages Glossary of terms i 1 Introduction 1 1.1. Scope and Objectives 1 1.2. Background and Context 1 1.3. Limitations 3 2 UK Geothermal Resource 4 2.1. History of Geothermal Energy Exploration in the UK 4 2.2. UK Geothermal Resources 4 2.3. Major Radiothermal Granites 5 2.4. Hot Sedimentary Aquifers 7 3 Phases of a Deep Geothermal Power Project 14 3.1. Introduction 14 3.2. Preliminary Survey 14 3.3. -

The United Downs Deep Geothermal Power Project Ryan Law1, Lucy

European Geothermal Congress 2019 Den Haag, The Netherlands, 11-14 June 2019 The United Downs Deep Geothermal Power Project Ryan Law1, Lucy Cotton2, Peter Ledingham3. 1 Geothermal Engineering Ltd, Falmouth Business Park, Bickland Water Road, Falmouth, Cornwall TR11 4SZ, UK [email protected] Keywords: Deep Geothermal, UK, United Downs. ABSTRACT The United Downs Deep Geothermal Power project is the first geothermal power project in the United Kingdom. It is located near Redruth in west Cornwall, UK and is part-funded by the European Regional Development Fund and Cornwall Council. The project consists of two deviated wells; a production well to a target depth of 4,500m and an injection well to a depth of 2,500m. Both wells target a sub-vertical, inactive fault structure that is thought will provide enhanced permeability relative to the surrounding granitic rock, sufficient to support circulation of between 20 and 60l/s. Geothermal gradients in Cornwall are relatively good and the bottom hole temperature is expected to be in the region of 190OC, allowing anticipated production to surface at greater than 175OC, which should allow electricity generation of between 1 and 3WMe. After funding agreements were signed in June 2017, a period of preparation and procurement followed, and Figure 1: Heatflow distribution in the UK (© BGS drilling began in November 2018. (NERC)). This paper places the project in the context of previous From the late 1970s until the early 1990s the Camborne geothermal research carried out in Cornwall, School of Mines managed a Hot Dry Rock geothermal summarises the concept and describes the site selection research programme at Rosemanowes Quarry, near work carried out. -

UK: Country Update for the United Kingdom

Proceedings World Geothermal Congress 2015 Melbourne, Australia, 19-25 April 2015 Country Update for the United Kingdom Tony Batchelor1, Robin Curtis1, Peter Ledingham1, Ryan Law2 1GeoScience Limited, Falmouth Business Park, Bickland Water Road, Falmouth, Cornwall, TR11 4SZ, UK 2Geothermal Engineering Limited, 82 Lupus St, London, SW1V 3EL, UK [email protected] Keywords: Country update, United Kingdom, low enthalpy, direct use, mine workings, coaxial heat exchanger, EGS, HDR, GSHP ABSTRACT The exploitation of geothermal resources in the UK continues to be minimal. There are no proven high temperature resources and limited development of low and medium enthalpy resources. However, in the reporting period 2010-2015, there has been a significant resurgence of interest in all aspects of geothermal energy in the UK. New geothermal assessments and reports have been produced, and several deep aquifer projects, minewater projects and EGS/HDR projects are at various preliminary stages. Two EGS/HDR projects in Cornwall have sites and planning approval. In terms of real activity "in the ground" a new deep hole has been drilled in the centre of Newcastle, and ground source heat pump installations have continued, albeit at a lower rate of growth than had been anticipated. A direct use, deep coaxial heat exchanger project is underway. "Geothermal" seminars and conferences have been held, and the UK has increasingly participated in EU and international geothermal initiatives. Compared to previous updates, there has been a significant awakening of geothermal interest in Scotland. Over this period there has been increasing recognition both at European and at UK national levels of the importance of delivering secure low carbon sources of heating. -

Notice Concerning Copyright Restrictions

NOTICE CONCERNING COPYRIGHT RESTRICTIONS This document may contain copyrighted materials. These materials have been made available for use in research, teaching, and private study, but may not be used for any commercial purpose. Users may not otherwise copy, reproduce, retransmit, distribute, publish, commercially exploit or otherwise transfer any material. The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specific conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be "used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research." If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. Hot Dry Rock Geothermal Energy Research at the Camborne School of Mines by ROGER PARKER, Project Director Camborne School of Mines Geothermal Energy Project, Rosemanowes Quarry, Herniss, Penryn, Cornwall, UK Introduction The Camborne School of Mines (CSM) Hot Dry placed. If-there is a need to incorporate specific localised Rock Geothermal Energy project in the period of 1977-89 geological structures in creating the reservoir, exploration has been concerned mainly with the technology of the costs (and the chances of a sterile operation) increase. development and characterisation of Hot Dry Rock Conversely, there is a need to avoid such structures in (HDR) reservoirs in a jointed granite.