A Framework for Planning & Implementing Anticorruption Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ejercicio 2 Bottle: Python Web Framework

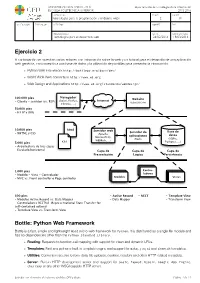

UNIVERSIDAD SAN PABLO - CEU departamento de tecnologías de la información ESCUELA POLITÉCNICA SUPERIOR 2015-2016 ASIGNATURA CURSO GRUPO tecnologías para la programación y el diseño web i 2 01 CALIFICACION EVALUACION APELLIDOS NOMBRE DNI OBSERVACIONES FECHA FECHA ENTREGA Tecnologías para el desarrollo web 24/02/2016 18/03/2016 Ejercicio 2 A continuación se muestran varios enlaces con información sobre la web y un tutorial para el desarrollo de una aplicación web genérica, con conexión a una base de datos y la utilización de plantillas para presentar la información. ‣ Python Web Framework http://bottlepy.org/docs/dev/ ‣ World Wide Web consortium http://www.w3.org ‣ Web Design and Applications http://www.w3.org/standards/webdesign/ Navegador 100.000 pies Website (Safari, Firefox, Internet - Cliente - servidor (vs. P2P) uspceu.com Chrome, ...) 50.000 pies - HTTP y URIs 10.000 pies html Servidor web Servidor de Base de - XHTML y CSS (Apache, aplicaciones datos Microsoft IIS, (Rack) (SQlite, WEBRick, ...) 5.000 pies css Postgres, ...) - Arquitectura de tres capas - Escalado horizontal Capa de Capa de Capa de Presentación Lógica Persistencia 1.000 pies Contro- - Modelo - Vista - Controlador ladores - MVC vs. Front controller o Page controller Modelos Vistas 500 pies - Active Record - REST - Template View - Modelos Active Record vs. Data Mapper - Data Mapper - Transform View - Controladores RESTful (Representational State Transfer for self-contained actions) - Template View vs. Transform View Bottle: Python Web Framework Bottle is a fast, simple and lightweight WSGI micro web-framework for Python. It is distributed as a single file module and has no dependencies other than the Python Standard Library. -

WEB2PY Enterprise Web Framework (2Nd Edition)

WEB2PY Enterprise Web Framework / 2nd Ed. Massimo Di Pierro Copyright ©2009 by Massimo Di Pierro. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Copyright owner for permission should be addressed to: Massimo Di Pierro School of Computing DePaul University 243 S Wabash Ave Chicago, IL 60604 (USA) Email: [email protected] Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created ore extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: WEB2PY: Enterprise Web Framework Printed in the United States of America. -

A Framework for PHP Program Analysis

A Framework for PHP Program Analysis Mark Hills Postdoc in Software Analysis and Transformation (SWAT) CWI Scientific Meeting February 8, 2013 http://www.rascal-mpl.org Overview • Motivation • Goals • Current Progress • Related Work 2 3 PHP: Not Always Loved and Respected • Created in 1994 as a set of tools to maintain personal home pages • Major language evolution since: now an OO language with a number of useful libraries, focused on building web pages • Growing pains: some “ease of use” features recognized as bad and deprecated, others questionable but still around • Attracts articles with names like “PHP: a fractal of bad design” and “PHP Sucks, But It Doesn’t Matter” 4 So Why Focus on PHP? • Popular with programmers: #6 on TIOBE Programming Community Index, behind C, Java, Objective-C, C++, and C#, and 6th most popular language on GitHub • Used by 78.8% of all websites whose server-side language can be determined, used in sites such as Facebook, Hyves, Wikipedia • Big projects (MediaWiki 1.19.1 > 846k lines of PHP), wide range of programming skills: big opportunities for program analysis to make a positive impact 5 Rascal: A Meta-Programming One-Stop-Shop • Context: wide variety of programming languages (including dialects) and meta-programming tasks • Typical solution: many different tools, lots of glue code • Instead, we want this all in one language, i.e., the “one-stop-shop” • Rascal: domain specific language for program analysis, program transformation, DSL creation PHP Program Analysis Goals • Build a Rascal framework for creating -

A Guide to Brazil's Oil and Oil Derivatives Compliance Requirements

A Guide to Brazil’s Oil and Oil Derivatives Compliance Requirements A Guide to Importing Petroleum Products (Oil and Oil Derivatives) into Brazil 1. Scope 2. General View of the Brazilian Regulatory Framework 3. Regulatory Authorities for Petroleum Products 3.1 ANP’s Technical Regulations 3.2 INMETRO’s Technical Regulations 4. Standards Developing Organizations 4.1 Brazilian Association of Technical Standards (ABNT) 5. Certifications and Testing Bodies 5.1 Certification Laboratories Listed by Inmetro 5.2 Testing Laboratories Listed by Inmetro 6. Government Partners 7. Major Market Entities 1 A Guide to Importing Petroleum Products (Oil and Oil Derivatives) into Brazil 1. Scope This guide addresses all types of petroleum products regulated in Brazil. 2. General Overview of the Brazilian Regulatory Framework Several agencies at the federal level have the authority to issue technical regulations in the particular areas of their competence. Technical regulations are always published in the Official Gazette and are generally based on international standards. All agencies follow similar general procedures to issue technical regulations. They can start the preparation of a technical regulation ex officio or at the request of a third party. If the competent authority deems it necessary, a draft regulation is prepared and published in the Official Gazette, after carrying out an impact assessment of the new technical regulation. Technical regulations take the form of laws, decrees or resolutions. Brazil normally allows a six-month period between the publication of a measure and its entry into force. Public hearings are also a way of promoting the public consultation of the technical regulations. -

For Fuel 1 (BDN) at 550, 1,100 and 1,650 Bar Injection Pressures

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Fatmi, Zeeshan (2018). Optical and chemical characterisation of the effects of high-pressure hydrodynamic cavitation on diesel fuel. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City, University of London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/22683/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] OPTICAL AND CHEMICAL CHARACTERISATION OF THE EFFECTS OF HIGH-PRESSURE HYDRODYNAMIC CAVITATION ON DIESEL FUEL Zeeshan Fatmi This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Mathematics, Computer Science and Engineering Department of Mechanical Engineering February 2018 i Table of Contents 2.1 Diesel Fuel................................................................................................................... 7 2.1.1 Distillation from Crude Oil and Conversion Processes ....................................... 7 2.1.2 Diesel Fuel Components .................................................................................... 10 2.1.3 Diesel Fuel Properties and Performance Parameters ........................................ -

Full-Length Envelope Analyzer (FLEA): a Tool for Longitudinal Analysis of Viral Amplicons

RESEARCH ARTICLE Full-Length Envelope Analyzer (FLEA): A tool for longitudinal analysis of viral amplicons Kemal Eren1, Steven Weaver2, Robert Ketteringham3, Morne Valentyn3, Melissa Laird 4,5 6 6 2 SmithID , Venkatesh Kumar , Sanjay Mohan , Sergei L. Kosakovsky Pond , 6,7 Ben MurrellID * 1 Bioinformatics and Systems Biology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA, 2 Department of Biology and Institute for Genomics and Evolutionary Medicine, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 3 Division of Medical Virology, Department of Pathology, Institute of Infectious Diseases and Molecular Medicine, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, Western Cape, South Africa, 4 Department of Genetics and a1111111111 Genomic Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA, 5 Icahn Institute of a1111111111 Genomics and Multiscale Biology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA, 6 Division of a1111111111 Infectious Diseases and Global Public Health, Department of Medicine, University of California San Diego, La a1111111111 Jolla, CA, USA, 7 Department of Microbiology, Tumor and Cell Biology, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, a1111111111 Sweden * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Abstract Citation: Eren K, Weaver S, Ketteringham R, Next generation sequencing of viral populations has advanced our understanding of viral Valentyn M, Laird Smith M, Kumar V, et al. (2018) population dynamics, the development of drug resistance, and escape from host immune Full-Length Envelope Analyzer (FLEA): A tool for longitudinal analysis of viral amplicons. PLoS responses. Many applications require complete gene sequences, which can be impossible Comput Biol 14(12): e1006498. https://doi.org/ to reconstruct from short reads. HIV env, the protein of interest for HIV vaccine studies, is 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006498 exceptionally challenging for long-read sequencing and analysis due to its length, high sub- Editor: TimotheÂe Poisot, Universite de Montreal, stitution rate, and extensive indel variation. -

Introducing Python

Introducing Python Bill Lubanovic Introducing Python by Bill Lubanovic Copyright © 2015 Bill Lubanovic. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472. O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://safaribooksonline.com). For more information, contact our corporate/ institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or [email protected]. Editors: Andy Oram and Allyson MacDonald Indexer: Judy McConville Production Editor: Nicole Shelby Cover Designer: Ellie Volckhausen Copyeditor: Octal Publishing Interior Designer: David Futato Proofreader: Sonia Saruba Illustrator: Rebecca Demarest November 2014: First Edition Revision History for the First Edition: 2014-11-07: First release 2015-02-20: Second release See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781449359362 for release details. The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Introducing Python, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and O’Reilly Media, Inc. was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in caps or initial caps. While the publisher and the author have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instruc‐ tions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the author disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. -

Muhammad Touqeer Shafi

Muhammad Touqeer Shafi E-mail: [email protected] CONTACT Website: http://pk.linkedin.com/pub/touqeer- shafi/22/634/b44/ Phone: +923142032499 WORK EXPERIENCE Ovrlod Pvt Ltd January 2014 — Present Software Engineer Design, program, and deliver web/local development projects (PHP, .Javascript and related platforms) within designated schedules. • Support development of projects from inception through alpha/beta testing and final delivery • Identify, communicate, and overcome development problems and creative challenges related to complex web • Keep current with programming languages/platforms within the web development/web application, and • Comprehend and follow specific project life-cycle instructions and procedures when required • Revise and troubleshoot development work as required • Provide tactical application mentorship to other developers in area of expertise • Heavily contribute to and actively follow technical documentation related to interactive development cycles • Act as a go-to person within technical area of expertise • Effectively present technical information in one-on-one and small group situations to vendors, clients, and agency staff • Apply common-sense understanding to carry out detailed but objective written or oral instructions • Engage in a pattern of learning and research Mamdani Web October 2011 — December 2013 Php Developer Write “clean”, well designed code. Produce detailed specifications. Troubleshoot, test and maintain the core product software and databases to ensure strong optimization and functionality. -

A Guide to Native Plants for the Santa Fe Landscape

A Guide to Native Plants for the Santa Fe Landscape Penstemon palmeri Photo by Tracy Neal Santa Fe Native Plant Project Santa Fe Master Gardener Association Santa Fe, New Mexico March 15, 2018 www.sfmga.org Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. ii Chapter 1 – Annuals and Biennials ........................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Chapter 2 – Cacti and Succulents ........................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 3 – Grasses ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Chapter 4 – Ground Covers .................................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Chapter 5 – Perennials......................................................................................................................................................................................... 11 Chapter 6 – Shrubs ............................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Redalyc.Effect of Deficit Irrigation on the Postharvest of Pear Variety

Agronomía Colombiana ISSN: 0120-9965 [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Colombia Colombia Bayona-Penagos, Lady Viviana; Vélez-Sánchez, Javier Enrique; Rodriguez-Hernandez, Pedro Effect of deficit irrigation on the postharvest of pear variety Triunfo de Viena (Pyrus communis L.) in Sesquile (Cundinamarca, Colombia) Agronomía Colombiana, vol. 35, núm. 2, 2017, pp. 238-246 Universidad Nacional de Colombia Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=180353882014 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Effect of deficit irrigation on the postharvest of pear variety Triunfo de Viena (Pyrus communis L.) in Sesquile (Cundinamarca, Colombia) Efecto del riego deficitario en la poscosecha de pera variedad Triunfo de Viena (Pyrus communis L.) en Sesquilé (Cundinamarca,Colombia) Lady Viviana Bayona-Penagos1, Javier Enrique Vélez-Sánchez1, and Pedro Rodriguez-Hernandez2 ABSTRACT RESUMEN A technique settled to optimize the use of water resources is Una técnica para optimizar el uso del recurso hídrico es el Riego known as Controlled Deficient Irrigation (CDI), for which this Deficitario Controlado (RDC), por esto se realizó un experi- experiment was carried out to determine the effect of a three mento para ver el efecto de tres láminas de agua correspondien- water laminae: 100 (T1), 25 (T2) and 0% (T3) crop´s evapotrans- tes al 100 (T1), 25(T2) y 0% (T3) de la evapotranspiración del piration (ETc) on the rapid growth phase of the pear fruit variety cultivo (ETc), en la fase de crecimiento rápido del fruto de pera Triunfo de Viena.The fruit quality (fresh weight variation, variedad Triunfo de Viena. -

Laravel in Action BSU 2015-09-15 Nathan Norton [email protected] About Me

Laravel in Action BSU 2015-09-15 Nathan Norton [email protected] About Me ● Full Stack Web Developer, 5+ years ○ “If your company calls you a full stack developer, they don’t know how deep the stack is, and neither do you” - Coder’s Proverb ● Expertise/Buzz words: ○ PHP, Composer, ORM, Doctrine, Symfony, Silex, Laravel, OOP, Design Patterns, SOLID, MVC, TDD, PHPUnit, BDD, DDD, Build Automation, Jenkins, Git, Mercurial, Apache HTTPD, nginx, MySQL, NoSQL, MongoDB, CouchDB, memcached, Redis, RabbitMQ, beanstalkd, HTML5, CSS3, Bootstrap, Responsive design, IE Death, Javascript, NodeJS, Coffeescript, ES6, jQuery, AngularJS, Backbone.js, React, Asterisk, Lua, Perl, Python, Java, C/C++ ● Enjoys: ○ Beer About Pixel & Line ● Creative Agency ● Web development, mobile, development, and design ● Clients/projects include Snocru, Yale, Rutgers, UCSF, Wizard Den ● Every employee can write code ● PHP/Laravel, node, AngularJS, iOS/Android ● “It sucks ten times less to work at Pixel & Line than anywhere else I’ve worked” - Zack, iOS developer Laravel ● Born in 2011 by Taylor Otwell ● MVC framework in PHP ● 83,000+ sites ● Convention over configuration ● Attempts to make working with PHP a joy ● Inspired by Ruby on Rails, ASP.NET, Symfony, and Sinatra ● Latest version 5.1, finally LTS Laravel Features ● Eloquent ORM ● Artisan command runner ● Blade Templating engine ● Flexible routing ● Easy environment-based configuration ● Sensible migrations ● Testable ● Caching system ● IoC container for easy dependency injection ● Uses Symfony components ● Web documentation -

Frameworks PHP

Livre blanc ___________________________ Frameworks PHP Nicolas Richeton – Consultant Version 1.0 Pour plus d’information : www.smile.fr Tél : 01 41 40 11 00 Mailto : [email protected] Page 2 les frameworks PHP PREAMBULE Smile Fondée en 1991, Smile est une société d’ingénieurs experts dans la mise en œuvre de solutions Internet et intranet. Smile compte 150 collaborateurs. Le métier de Smile couvre trois grands domaines : ! La conception et la réalisation de sites Internet haut de gamme. Smile a construit quelques uns des plus grands sites du paysage web français, avec des références telles que Cadremploi ou Explorimmo. ! Les applicatifs Intranet, qui utilisent les technologies du web pour répondre à des besoins métier. Ces applications s’appuient sur des bases de données de grande dimension, et incluent plusieurs centaines de pages de transactions. Elles requièrent une approche très industrielle du développement. ! La mise en œuvre et l’intégration de solutions prêtes à l’emploi, dans les domaines de la gestion de contenus, des portails, du commerce électronique, du CRM et du décisionnel. www.smile.fr © Copyright Smile - Motoristes Internet – 2007 – Toute reproduction interdite sans autorisation Page 3 les frameworks PHP Quelques références de Smile Intranets - Extranets - Société Générale - Caisse d'Épargne - Bureau Veritas - Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique - Visual - Vega Finance - Camif - Lynxial - RATP - AMEC-SPIE - Sonacotra - Faceo - CNRS - AmecSpie - Château de Versailles - Banque PSA Finance - Groupe Moniteur - CIDJ - CIRAD - Bureau