The Struggle Over Appropriate Recreation in Yosemite National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dean Potter, Extreme Climber, Dies in Base-Jumping

POWER(linear): Units 10 & 11 Dr John P. Cise, Professor of Physics, Austin Community College, 1212 Rio Grande St., Austin Tx. 78701 [email protected] & NY Times May 17, 2015 by John Branch Dean Potter, Extreme Climber, Dies in Base-Jumping Accident at Yosemite Dean Potter, one of the generation’s top rock climbers and charismatic personalities, was one of two men killed in a BASE-jumping accident at Yosemite National Park in California on Saturday. Potter, 43, and the other man, Graham Hunt, 29, leapt near dusk off Taft Point, a promontory about 3,000 feet above the floor of Yosemite Valley, not far from the iconic granite masses of El Capitan and Half Dome. Flying in wingsuits, they tried to clear a notch in the granite cliffs but instead smashed into the rocks in quick succession. “It’s tremendously sad,” said Gauthier, an occasional climbing partner of Potter, who lived in Yosemite. “Dean was part of this community and had such an impact on climbing. He was a luminary and in the pantheon of climbing gods.” INTRODUCTION: Half Dome mountain at left in Yosemite National Park is 4800 feet from valley floor to summit. QUESTION: (a) How much gravitational potential energy did Dean Potter gain in climbing Half Dome? Do in English system (b) How much work did he do during this 4800 ft. climb? (c) Convert 1 hr + 19 min. to seconds? (d) How powerful was Dean during the climb? (in units of ft. lb./s) . (e) Find his Dean Potter was one of two men killed while BASE jumping in Yosemite National Park. -

New Routes, Major Linkups, and Speed Ascents

AAC Publications Summary: new routes, major linkups, and speed ascents California, Yosemite National Park In addition to the routes described in more detail in this section, as well as Mikey Schaefer’s Father Time route on Middle Cathedral [see feature article in this AAJ], there are a few other significant new routes to report from Yosemite Valley in 2012. Luis “Lucho” Rivera and Dan McDevitt free-climbed Romulan Freebird (10 pitches, V 5.12b/c) on Fifi Buttress, across from the Leaning Tower. McDevitt first established the route as an aid climb in 1999. The free version is described as a harder version of the Rostrum, with thin and sustained 5.12 cracks. Additionally, Alex Honnold set out to free the 1,550’ west face of the Leaning Tower, freeing the lower portion of the wall directly via a hard slab he called A Gift From Wyoming (550’, 3 pitches, 5.13c), in honor of the late Todd Skinner, who originally projected the upper west face. The upper portion, a potential free version of the aid route Jesus Built My Hotrod, is estimated at hard 5.14 or even 5.15 and awaits a successful redpoint. Video #2: BD athlete Alex Honnold making the first ascent of A Gift From Wyoming (5.13) on Yosemite's Leaning Tower from Black Diamond Equipment on Vimeo. Alex Honnold and Tommy Caldwell completed the first free one-day ascent of the “Yosemite Triple,” which linked the south face of Mt. Watkins, Freerider on El Capitan, and the Regular Northwest Face on Half Dome—about 7,000’ vertical—in a combined time of 21:15 from the base of Mt. -

Genre Bending Narrative, VALHALLA Tells the Tale of One Man’S Search for Satisfaction, Understanding, and Love in Some of the Deepest Snows on Earth

62 Years The last time Ken Brower traveled down the Yampa River in Northwest Colorado was with his father, David Brower, in 1952. This was the year his father became the first executive director of the Sierra Club and joined the fight against a pair of proposed dams on the Green River in Northwest Colorado. The dams would have flooded the canyons of the Green and its tributary, Yampa, inundating the heart of Dinosaur National Monument. With a conservation campaign that included a book, magazine articles, a film, a traveling slideshow, grassroots organizing, river trips and lobbying, David Brower and the Sierra Club ultimately won the fight ushering in a period many consider the dawn of modern environmentalism. 62 years later, Ken revisited the Yampa & Green Rivers to reflect on his father's work, their 1952 river trip, and how we will confront the looming water crisis in the American West. 9 Minutes. Filmmaker: Logan Bockrath 2010 Brower Youth Awards Six beautiful films highlight the activism of The Earth Island Institute’s 2011 Brower Youth Award winners, today’s most visionary and strategic young environmentalists. Meet Girl Scouts Rhiannon Tomtishen and Madison Vorva, 15 and 16, who are winning their fight to green Girl Scout cookies; Victor Davila, 17, who is teaching environmental education through skateboarding; Alex Epstein and Tania Pulido, 20 and 21, who bring urban communities together through gardening; Junior Walk, 21 who is challenging the coal industry in his own community, and Kyle Thiermann, 21, whose surf videos have created millions of dollars in environmentally responsible investments. -

Learning to Fly: an Uncommon Memoir of Human Flight, Unexpected Love, and One Amazing Dog by Steph Davis

AAC Publications Learning to Fly: An Uncommon Memoir of Human Flight, Unexpected Love, and One Amazing Dog By Steph Davis Learning to Fly: An Uncommon Memoir of Human Flight, Unexpected Love, and One Amazing Dog. Steph Davis. Simon & Schuster, 2013. 304 pages. Hardcover. $24.99 Steph Davis’ second book picks up shortly after the release of her first, High Infatuation: A Climber’s Guide to Love and Gravity, in which readers move through her childhood, her introduction to adventure sports, and some of her more notable climbing feats (a one-day ascent of Torre Egger and free- climbing Salathé Wall, among others). In Learning To Fly, we meet Davis as she leaves for a countrywide tour to promote her first book. She is managing the fallout from what she refers to as “the incident”: her then-husband Dean Potter’s controversial 2006 ascent of Delicate Arch in the Utah desert, which led to a media uproar, a heated community-wide discussion, and both Potter and Davis being dropped by their primary sponsors. By page 13, she writes that she “was without a marriage, without a paycheck, and pretty much without a career. In a life defined by risk and uncertainty, almost all of my anchors were gone.” So Davis did what the rest of us wish we could do when we get fed up with climbing: She took her dog, Fletch, and her pickup truck to Colorado and spent a summer learning to skydive. Living on savings, she couch-surfs near the drop zone, jumps out of airplanes as often as possible, and finds a new life philosophy: “When death holds no more fear and when you’ve lost the things most precious to you, there’s nothing more to be afraid of.” By the end of summer she has grown to love the feeling of falling, come to terms with her failed marriage, and found her way back to climbing with a free-solo of the Diamond on Longs Peak. -

The Impact of Social Media Presentation on Rock Climbing

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-1-2020 Virtually Invincible: The Impact of Social Media Presentation on Rock Climbing Lilly Posner Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Repository Citation Posner, Lilly, "Virtually Invincible: The Impact of Social Media Presentation on Rock Climbing" (2020). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 3945. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/19412154 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VIRTUALLY INVINCIBLE: THE IMPACT OF SOCIAL MEDIA PRESENTATION ON ROCK CLIMBING By Lilly Posner Bachelor of Arts – Film Production Brooklyn College, CUNY 2003 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts – Journalism & Media Studies -

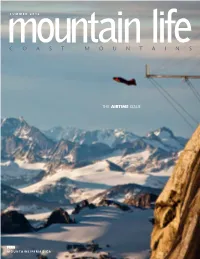

The Airtime Issue

SUMMER 2012 THE AIRTIME ISSUE Helly Hansen catwalk Scandinavian Design is the cornerstone in all Helly Hansen gear. The optimal combination of purposeful design, protection and style. This is why professional mountain guides, patrollers and discerning enthusiasts choose Helly Hansen. cOnFIDent wHen It MatteRs Helly HanSen WeSTin ReSoRT Helly HanSen WHiSTleR Village STRoll Helly HanSen gRanVille 115-4090 WHiSTleR Way 108-4295 BlaCkComB Way 766 gRanVille STReeT WHiSTleR BC (604)932-0142 WHiSTleR BC VanCouVeR (604) 609-3932 DAILY BEAR VIEWING TOURS BEARS2 Hour Tours $119 Guests Under 16yrs $89 Private & Semi-Private Bear Viewing Eco-Tours Toll Free Enjoy one of the premier black bear viewing spots in Whistler. 1.888.501.4845 James Fougere, a local naturalist and wildlife photographer, will Local 1.604.966.7385 guide you on your wilderness black bear safari. Starti ng in May, black bears emerge from hibernati on and begin to feed on the new spring growth. www.WhistlerDiscoveryTours.com [email protected] This adventure will leave you appreciati ve of our natural world. Avid photographers will fi nd this a prime opportunity to capture stunning images! WHISTLER LAND ROVER EXCURSIONS Visit whistlerdiscoverytours.com for more Eco-Tours. : DANIELLE BALIK RIDER: PAT MULROONEY : DANIELLE BALIK RIDER: PAT FOR THOSE WHO KNOW NO BOUNDS. Adventures shouldn’t have boundaries and neither should your equipment. With 140mm of go-anywhere, ride-anything A.R.T. travel giving it equal prowess on the way up and on the way down, the Sight always delivers a ride without limits. norco.com johnhenrybikes.com riderepublic.com fanatykco.com 100-400 Brooksbank Ave, North Vancouver 1- 41340 Government Road, Squamish Unit # 6 - 4433 Sundial Place, Whistler 604.986.5534 604.898.1953 604.938.9455 UNLIMITED ADVENTURES. -

For Office.Use -';11

/' FOR OFFICE.USE -';11 I .I I ; I "~ II ~ ~ i ~ i i ~ ~ I ! i I ;;:~ .~ J A3 I .'t,. ., ~ , Twospeeddemonshaveturnedthemostfamousbigwallofall intoaverticalracetrack,butastheyrushtoglory,theirpeers THEwonder:Howlongbeforea spectacular-andlethal-crash? II"' II:" t: CLIMBINGWAR BY YI-WYN YEN utes when Herson stopped to fixa broken shoelace, they covered the route in 3:57:27. This time Florine rushed to congratulate himself, sending out a snarky e-mail to sev- HE NEWS spread through Yosemite eral climbers, including Potter and O'Neill. "Even I'll Valleylast Oct. 15like a Santa Ana wild- admit this one is goingto be hard to break;' Florine wrote. fire: Dean Potter and Tim O'Neill had Turns out it wasn't hard to break at all. On the morn- scaled EI Capitan's Nose route in less ing ofNov.2, Potter,30, and O'Neill,33, eclipsed Florine's than four hours-three hours, 59 minutes and 35 sec- mark by a half hour, in view of their nemesis, who for onds, to be exact-a benchmark previouslybelieved to be five straight mornings had dropped offhis infant daugh- as untouchable as the four-minute mile had once been ter, Marianna, at a day-care center and raced over to for runners. Word of the feat, as it so often does when it Yosemite Meadow to see if his rivalswere on EICap. Un- involves Potter, soon reached Hans Florine, who had bowed, Florine resolved to launch another assault on the Nose, but it had to wait: the day before he had broken 11'1 held the Nose record of 4:22. -

TREADWALL CHALLENGE Climber: Climbing

TREADWALL CHALLENGE Climber: Climbing Log Hald Dome - Regular NW Face Pitch Crux Vert Feet Start Time Distance Time Date 1 5.11 160 2 5.9 100 3 5.8 105 4 5.10a 110 5 5.9 100 6 5.9 145 7 5.8 135 8 scramble 120 9 5.9 100 10 5.12c A0 80 11 5.10a 80 12 5.11c 130 13 5.7 100 14 5.9 70 15 5.9 100 16 5.9 100 17 5.9 100 18 5.12a 100 19 5.12a 120 20 5.9 40 21 5. 90 22 5.12a 90 23 5.7 120 24 scramble 200 TOTAL 2595 TREADWALL – Triple Crown Challenge GOAL - Climb the same vertical meters of every "Pitch" of Yosemite’s Triple Crown challenge using the Source Treadwall. Background - The Triple Crown is a challenge to climb the three biggest walls in Yosemite – El Cap, Mt. Watkins, and Half Dome – in a single day. The only people that have successfully completed the linkup are some of the best climbers in the history of Yosemite. The Triple Crown was first climbed in 2001 by Dean Potter and Timmy O'Neill, the speed-climbing dream team that broke Hans Florine and Peter Croft's nine-year-old speed record on the Nose of El Capitan. Unlike Honnold and Caldwell, Potter and O'Neill aided their way through difficult sections, using gear to support their weight rather than pulling on holds. Dean Potter and Timmy O’Neal completed the climb in 21 hours and 37 minutes. -

Guardian and Observer Editorial

The Women’s Issue EXTREME SPORTS High-risk sports were once considered just for men and a woman’s place was to watch from a safe distance. Times have changed . Three women adventurers describe the thrill and dangers of life on the edge STEPH DAVIS Yosemite Valley , using just her Patagonia in South America, where by impulse,’ she says. ‘In reality ROCK CLIMBER hands and feet to make progress the wind blows hard and almost it was never a choice, but rather a and relying on her rope only to constantly, confi ning climbers to surrender to the inevitable.’ stop a fall. Called ‘free climbing’, base camp for weeks on end. She was born into a respectable, aped to the refrigerator in this style is regarded as just about hard-working family far from the TSteph Davis’s mobile home the purest form of ascending the She has returned to Patagonia mountains, in Maryland. She is a scrap of paper with the valley’s big granite walls. again and again, often unrewarded only discovered climbing as an earnest thought that ‘struggle is Davis has been right in the midst but sometimes snatching a prize, undergraduate. To her family’s part of life, and once we accept of this dizzying revolution. In 2003 , such as the fi rst female ascent horror, she ditched plans to be a that, things will be much easier’. she became only the second woman of Torre Egger , a vast needle of lawyer in favour of a life scraping There has been no shortage to free climb Yosemite’s legendary vertical granite that she climbed together sponsorship deals and of struggle in the 34-year-old El Capitan . -

NPS-FOIACASELOG-2013-2015.Pdf

This document is made available through the declassification efforts and research of John Greenewald, Jr., creator of: The Black Vault The Black Vault is the largest online Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) document clearinghouse in the world. The research efforts here are responsible for the declassification of hundreds of thousands of pages released by the U.S. Government & Military. Discover the Truth at: http://www.theblackvault.com FY2014 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE FOIA LOG REGION REQUEST NO. REQUESTED COMPLETED LAST NAME SUBJECT ALL DOCUMENTS RELATED TO PERMIT #13-1563 WHICH WAS REQUESTED BY A GROUP CALLED THE 2 MILLION BIKERS TO DC FOR A NON STOP BIKE RIDE THAT WAS TO TAKE PLACE IN AND AROUND NCRO NPS-2014-00002 09/12/13 10/23/13 SHANNON THE NATIONAL MALL ON SEPTEMBER 11TH, 2013 IMRO NPS-2014-00007 09/25/13 10/01/13 AMSDEN YELL-SUSAN WASSERMAN IMRO NPS-2014-00008 09/26/13 10/01/13 GARDEN CAVE : CONCESSION CONTRACT IMRO NPS-2014-00009 09/26/13 10/01/13 GARDEN YELL: CONCESSION CONTRACT IMRO NPS-2014-00010 09/26/13 10/01/13 GARDEN ROMO: CONCESSION CONTRACT IMRO NPS-2014-00011 09/26/13 10/01/13 GARDEN ZION: CONCESSION CONTRACT IMRO NPS-2014-00012 09/26/13 10/01/13 GARDEN WHSA: CONCESSION CONTRACT A LIST OF ALL UNREPRESENTED BARGAINING UNIT ELIGIBLE EMPLOYEES (TYPICALLY CODED 7777) IN THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE'S (NPS) NCRO (NCR), INCLUDING LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS AND SECURITY NCRO NPS-2014-00013 10/08/13 10/28/13 RAY GUARDS. MABO: CONTRACT INPC2350064026 ORDER INPT2350097517: 1) TASK PWRO NPS-2014-00014 10/03/13 11/07/13 SANTOS ORDER; 2) SOW; 3) ALL MODIFICATIONS. -

Psychiatric Aspects of Extreme Sports

ORIGINAL RESEARCH & CONTRIBUTIONS Special Report Psychiatric Aspects of Extreme Sports: Three Case Studies Ian R Tofler, MBBS; Brandon M Hyatt, MFT; David S Tofler, MBBS Perm J 2018;22:17-071 E-pub: 01/15/2018 https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/17-071 ABSTRACT enhancing transcendent primal drive skiing are two examples). The 2010 death Extreme sports, defined as sporting akin to attainment of a “flow experi- of third-generation Georgian luge com- or adventure activities involving a high ence.”3 Conquering the “death wish” petitor Nodar Kumaritashvili during degree of risk, have boomed since the (Thanatos drive), overcoming paralyzing practice at the Vancouver Winter Olym- 1990s. These types of sports attract fear, and searching for a transformative pic Games is testament to this fact.11 men and women who can experience a or “life wish” (Eros drive) are consid- Geneticists have explored possible life-affirming transcendence or “flow” as ered integral motivators for the extreme links between a propensity for high-risk they participate in dangerous activities. sportsperson.1,2,4 Available leisure time; activities and genetic markers. The puta- Extreme sports also may attract people abundant finances; and sophisticated tive connection of polymorphisms of the with a genetic predisposition for risk, risk- yet affordable equipment attract upper D4 subtype of the dopamine 2 receptor, a seeking personality traits, or underlying and middle class participants, enabling G protein-coupled receptor that inhibits psychiatric disorders in which impulsivity them to temporarily escape constrained adenylyl cyclase, with risk-taking, novelty- and risk taking are integral to the underly- socially acceptable and defined roles and seeking behavior in humans and other ing problem. -

Die Laureus World Sports Awards

FAST FACTS – DIE LAUREUS WORLD SPORTS AWARDS Die jährliche Vergabe der Laureus World Sports Awards ist die einzige weltweite Preisverleihung, mit der die besten Sportlerinnen und Sportler für ihre Leistungen in allen Disziplinen geehrt werden. Die Laureus World Sports Awards wurden am 27. Februar 2018 zum 19. Mal vergeben. Jährlich verfolgen mehrere Millionen Zuschauer in 160 Ländern die Laureus-Zeremonie. Die Laureus World Sports Awards wurden im Jahr 1999 durch die Daimler AG und Richemont ins Leben gerufen. Die zu der Daimler AG und Richemont gehörenden Marken Mercedes-Benz und IWC Schaffhausen sind die Hauptpartner von Laureus. Es gibt ein zweiteiliges Auswahlverfahren zur Ermittlung der Gewinner der Laureus World Sports Awards. Zuerst nominiert ein Gremium von weltweit führenden Sportredakteuren, Sportautoren und Sportreportern aus über 100 Ländern sechs Personen (bzw. Teams) für jede Kategorie. Die Stimmen werden durch die unabhängige Wirtschaftsprüfungsgesellschaft Pricewaterhouse Coopers LLP kollationiert, dann bestimmen die Mitglieder der Laureus World Sports Academy in geheimer Wahl die Gewinner. Die Laureus World Sports Academy besteht aus über 60 legendären Sportlerinnen und Sportlern aus der ganzen Welt. Ihr Vorsitzender ist die neuseeländische Rugby-Legende Sean Fitzpatrick. Es gibt fünf Kategorien, die von den internationalen Medien und der Akademie gewählt werden: Laureus World Sportsman of the Year, Laureus World Sportswoman of the Year, Laureus World Team of the Year, Laureus World Breakthrough of the Year und Laureus World Comeback of the Year. In zwei weiteren Kategorien wird von Spezialistengremien gewählt: der/die Laureus World Action Sportsperson of the Year, von weltweit führenden Berichterstattern des alternativen Sports und der/die Laureus World Sportsperson of the Year with a Disability; diese Kategorie wird vom Exekutivkomitee des Internationalen Paralympischen Komitees bestimmt.