Is Abstract Artefact Theory a Plausible Version of Realism About Fictional Characters? Jack Waites - the University of Sheffield Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Options Advice Matthew Thompson & Ro Bartram

February 2020 Issue School Newspaper Options Advice Matthew Thompson & Ro Bartram For the Year 9’s, the time has come for them to choose their GCSE’s. This is the first time you can make a choice about your education and it is important that you make these choices wisely as to not waste the next two years. If you are lucky enough to have a career focus already, this is a great opportunity to pick the GCSE options which best suit this and invest your time and effort into that. On the other hand, if you are clueless in regards to your career, all hope is not lost, as even A-level students do not yet know where they will go next. During GCSE’s it is recommended that you pick at least two that you enjoy, as it will become increasingly harder to motivate yourself if you pick options which you quite frankly couldn't care less about. You mustn’t let others influence what subjects you pick. Not your teachers, not your friends and not your parents. THIS IS ABOUT YOU. To stop you from picking subjects based purely on what the teachers say to you, talk to the older years about what the subjects entail as they will have the experience and be able to tell you unbiased accounts of what they are like. We are more than happy to give the insight that we wish we had from older years when we were at this stage. If disaster strikes and the blocks do not allow you to take the options you want, there are still ways around this. -

Refugee Week Survey 10-006797

Refugee Week Survey (10-006797) Refugee Week Survey 10-006797 Topline Results June 2010 • Results are based on all respondents (327) unless otherwise stated. • Fieldwork was between 27th April 2010 and 29th May 2010. • Where results do not sum to 100, this is due to multiple responses. • An * indicates a score less than 0.5%, but greater than zero. Q1. From the following, which, if any, do you MOST enjoy about living in Britain? Please select up to three. % The British people 44 Football 42 Multicultural society 41 British TV 34 Shops 26 Countryside 24 History 22 The Royal Family 13 British food e.g. Fish and chips, Sunday 11 roasts British music 10 Drinking tea 8 Pubs 2 None of these 1 Don’t know * Q2. From the following, which characteristics, if any, do you think BEST represent British people? Please select up to three. % Friendly 52 Polite 35 Obsessed with football 27 Hard-working 26 Kind 23 Apologetic 21 Tolerant 20 Easy-going 19 Cheerful 16 Reserved 11 Complaining 10 Humorous 9 Sarcastic 6 None of these 1 Don’t know 1 FINAL Topline Results 1 Refugee Week Survey (10-006797) Q3. From the following, which, if any of these British people do you MOST admire? Please select up to three. % The Queen 49 Princess Diana 48 David Beckham 41 William Shakespeare 33 Cheryl Cole 18 Winston Churchill 12 Trevor McDonald 10 Charles Darwin 9 John Lennon 9 Charles Dickens 9 David Attenborough 7 Paul McCartney 5 Michael Palin 4 Dizzee Rascal 2 J.K. Rowling 2 No-one 3 Don’t know 2 Q4. -

ON UNEVEN GROUND the Multiple and Contested Nature(S) of Environmental Restoration

ON UNEVEN GROUND The Multiple and Contested Nature(s) of Environmental Restoration Laura Smith Cardiff School of City and Regional Planning Cardiff University PhD Thesis 2009 UMI Number: U584441 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U584441 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed...................................... (candidate) Date .. 22 . £.993... STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. Signed...................................... (candidate) Date ..}. ?. STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. Signed...................................... (candidate) Date .. A?, . ?.? ?. ?.. STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed.......................................... (candidate) Date . .f.2: STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Graduate Development Committee. -

Free, M. (2015) Don't Tell Me I'm Still...Pdf

Pre-publication version. This is scheduled for publication in the journal Critical Studies in Television, Vol. 10, Summer 2015. It should be identical to the published version, but there may be minor adjustments (typographical errors etc.) prior to publication. Title: ‘Don’t tell me I’m still on that feckin’ island’: Migration, Masculinity, British Television and Irish Popular Culture in the Work of Graham Linehan Author: Marcus Free, Mary Immaculate College, University of Limerick – [email protected] Abstract The article examines how, through such means as interviews and DVD commentaries, television situation comedy writer Graham Linehan has discursively elaborated a distinctly migrant masculine identity as an Irish writer in London. It highlights his stress on how the working environment of British broadcasting and the tutelage of senior British broadcasters facilitated the satirical vision of Ireland in Father Ted. It focuses on the gendering of his narrative of becoming in London and how his suggestion of interplays between specific autobiographical details and his dramatic work have fuelled his public profile as a migrant Irish writer. Graham Linehan has written and co-written several situation comedies for British television, including Father Ted (with Arthur Mathews – Channel 4, 1995-98); Black Books (with Dylan Moran – Channel 4, 2000-2004 (first series only)); The IT Crowd (Channel 4, 2006- 13); and Count Arthur Strong (with Steve Delaney – BBC, 2013-15). Unusually, for a television writer, he has also developed a significant public profile in the UK and Ireland through his extensive interviews and uses of social media. Linehan migrated from Dublin to London in 1990 and his own account of his development as a writer stresses his formation through the intersection of Irish, British and American influences. -

He Who Dares: My Geniune Autobiography Free

FREE HE WHO DARES: MY GENIUNE AUTOBIOGRAPHY PDF Derek 'Del Boy' Trotter | 320 pages | 08 Oct 2015 | Ebury Publishing | 9780091960032 | English | London, United Kingdom DEL BOY HE WHO DARES: My Genuine Autobiography - Bibliophile Books This classic guide to Istanbul by Hilary Summer-Boyd and John Freely - the 'best travel guide to Istanbul' "The Times"'a guide book that reads like a novel' "New York Times" - is here, for the first time since its original publication thirty-seven This text brings statistical tools to engineers and scientists who design and develop new products, He Who Dares: My Geniune Autobiography manufacturing systems and processes and who improve existing systems. Because computer-intensive methods are so important in the modern use of statistics, In the land of Westeros, a timely message dispatched via raven can make the difference between winning a battle and losing your kingdom. These deluxe stationery kits, themed to the Great Houses of Westeros, provide all the items you need to communicate Ciltli İngilizce Sayfa 16,41x24,21x3,2 cm. Jack-the-lad, wheeler-dealer and international playboy just ask the manageress of El Sid's, Torremolinos,this was a man destined for greatness. A He Who Dares: My Geniune Autobiography of nature, a man who beat the odds, if only for a bit. This is his story. The story of Derek 'Del Boy' Trotter. Who else could tell the glorious tale of rags to riches to rags to rich ish but the man himself? Sepete Eklendi. Sepette Var. Applied Statistics and Probability for Engineers 6e ISV This text brings statistical tools to engineers and scientists who design and develop new products, new manufacturing systems and processes and who improve existing systems. -

PDF Download Only Fools and Horses: the Untold Story of Britains

ONLY FOOLS AND HORSES: THE UNTOLD STORY OF BRITAINS FAVOURITE COMEDY Author: Professor Graham McCann Number of Pages: 352 pages Published Date: 23 Nov 2011 Publisher: Canongate Books Ltd Publication Country: Edinburgh, United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9780857860545 DOWNLOAD: ONLY FOOLS AND HORSES: THE UNTOLD STORY OF BRITAINS FAVOURITE COMEDY Only Fools and Horses: The Untold Story of Britains Favourite Comedy PDF Book Using fresh research, keen observation and a wealth of cultural references, Bradley weaves from this network a remarkable story of technological achievement, of architecture and engineering, of shifting social classes and gender relations, of safety and crime, of tourism and the changing world of work. Olick looks at how catastrophic, terrible pasts - Nazi Germany, apartheid South Africa - are remembered, but he is particularly concerned with the role that memory plays in social structures. Some who were invited did not arrive, so there are gaps in expertise that we could not supply. Veterinary Advice on Colic in HorsesA Good Life for a Horse's Golden Years. By crepitation is meant that characteristic grating sound produced by rubbing the two ends of the fractured bone together It is the one absolute sign of a fracture, and once heard can never be forgotten. The present volume is organized in seven chapters. Consistent standards provide appropriate benchmarks for all students, regardless of where they live. Part Five considers the power of collaboration for generating the culture needed to improve the sustainability of our global community. That is the reason they are used in making deodorants and body sprays as well. You won't just get more customers, you'll get more profitable customers. -

A History of Brexit in 47 Objects: the Story of Leave Page 1 of 9

LSE Brexit: A History of Brexit in 47 Objects: The Story of Leave Page 1 of 9 A History of Brexit in 47 Objects: The Story of Leave In the third part of his nine-part series on the history of Brexit, Tim Oliver (Loughborough University London) looks at six objects through which we can understand why the Leave campaign won. Why the Leave campaign won remains one of the most debated questions in British politics. That’s because there is, of course, no straightforward answer. The six objects through which the story of Leave is told look for answers in the UK’s constitutional setup, the successful messengers and messages (especially on immigration) of the various Leave campaigns, the role of a largely Eurosceptic press, and how the topic of Brexit worked its way deep into the issues that divide British society. Object 7: A 2016 EU Referendum Ballot Paper Image: public domain. This mundane, functional slip of paper might not be the most colourful or exciting object in the series. That would be to overlook the many controversies that lie behind this little slip of paper. More precisely, if every eligible voter had cast their vote then there were potentially 46,500,001 little slips of paper. The numbers themselves speak of them playing a part in a successful act of democracy. 33,577,342 eligible voters, or 72.21%, put their mark on this little slip of paper, a turnout higher than any general election since 1992. Unlike in general elections where voters in a small number of marginal constituencies decide the overall result, everyone’s referendum vote matters equally. -

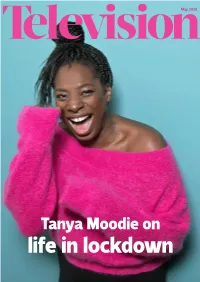

Tanya Moodie on Life in Lockdown BRINGING WORLDS to LIFE Find the Sound of Your Story at Audionetwork.Com/Discover/Sound-And-Story

May 2020 Tanya Moodie on life in lockdown BRINGING WORLDS TO LIFE Find the sound of your story at audionetwork.com/discover/sound-and-story FIND OUT MORE : Naomi Koh | [email protected] | +44 (0)207 566 1441 Journal of The Royal Television Society May 2020 l Volume 57/5 From the CEO I am thrilled that the Two sitcom Motherland and Break- the bursary scheme, has written a Society’s online events through Award-winner at the RTS moving account of how young lives have started in earnest, Programme Awards in March. have been put on hold. including a Q&A with Talking of comedy, in these testing We also speak to the indefatigable Russell T Davies from times the ability to kindle laughter is Ben Frow, head of programmes at RTS North West and a precious gift. In the first of a new Channel 5, voted Channel of the Year “News in the new series, Comfort Classic, Matthew Bell at the RTS Programme Awards. norm” from RTS Thames Valley. Both examines the enduring appeal of that Finally, this month’s expanded TV attracted large and engaged audiences. great sitcom Only Fools and Horses. Diary is a candid account of how We now also have weekly events The BBC has stepped up to the plate screenwriter and doctor Dan Sefton for our RTS Futures community and with its Bitesize educational initiative. has returned to the front line of medi- some exciting “In conversation with…” Maggie Brown describes how it is help- cine during the pandemic. He is one evenings, webinars and virtual screen- ing the nation’s schoolchildren to carry of the heroes keeping our country ings and discussions to come. -

The Economist

Statisticians in World War II: They also served | The Economist http://www.economist.com/news/christmas-specials/21636589-how-statis... More from The Economist My Subscription Subscribe Log in or register World politics Business & finance Economics Science & technology Culture Blogs Debate Multimedia Print edition Statisticians in World War II Comment (3) Timekeeper reading list They also served E-mail Reprints & permissions Print How statisticians changed the war, and the war changed statistics Dec 20th 2014 | From the print edition Like 3.6k Tweet 337 Advertisement “I BECAME a statistician because I was put in prison,” says Claus Moser. Aged 92, he can look back on a distinguished career in academia and civil service: he was head of the British government statistical service in 1967-78 and made a life peer in 2001. But Follow The Economist statistics had never been his plan. He had dreamed of being a pianist and when he realised that was unrealistic, accepted his father’s advice that he should study commerce and manage hotels. (“He thought I would like the music in the lobby.”) War threw these plans into disarray. In 1936, aged 13, he fled Germany with his family; four years later the prime minister, Winston Churchill, decided that because some of the refugees might be spies, he would “collar the lot”. Lord Moser was interned in Huyton, Latest updates » near Liverpool (pictured above). “If you lock up 5,000 Jews we will find something to do,” The Economist explains : Where Islamic he says now. Someone set up a café; there were lectures and concerts—and a statistical State gets its money office run by a mathematician named Landau. -

Only Fools and Horses : the Story of Britains Favourite Comedy Kindle

ONLY FOOLS AND HORSES : THE STORY OF BRITAINS FAVOURITE COMEDY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Graham McCann | 368 pages | 07 Jun 2012 | Canongate Books Ltd | 9780857860569 | English | Edinburgh, United Kingdom Only Fools and Horses : The Story of Britains Favourite Comedy PDF Book Gilbert used to judge matters by the axiom 'Will they understand it in Wick? Story: Two siblings share their Friday night dinners at their parents home and, somehow, something always goes wrong. Written by Simon Amstell and long term collaborator Dan Swimer, the series stars Simon Amstell playing a version of himself: an ex-television presenter searching for meaning in Many had a natural 'gift of the gab'. The Office. Original name: Only Fools and Horses. Load More Movies. There are also the classics which never grow old, and some of them have earned the top spot for the best-loved Christmas special. Raised by Wolves Buy and sell old and new items Search for this product on eBay. The BBC had of course produced their own 'story' of 'Only Fool's, the beloved sitcom back in , but it never really felt complete what with the episode still to air, and the spin-offs that were made later. One Foot In The Grave. Plot: working class , family business, father, son, reluctant partners, odd couple, lifestyle, society , parents and children, urban, city life, workplace situations The Thick of It No thanks. First published: Thursday 3rd November Look for them in the presented list. Trailers and Videos. Episode Guide. Phoenix Nights Yes No. Find it at SL. Style: sitcom , humorous , semi serious , realistic. -

WHERE CHRISTMAS COMES Together

TWHEoRgE CeHtRIShTMeASr COMES HILTON AVISFORD PARK, ARUNDEL We have all you need to celebrate Christmas in style. FOR MORE INFORMATION Contact the Christmas team on +44 (0)1243 558 308 [email protected] WHERE CHRISTMAS COMES Together It’s the most wonderful time of the year, so spend it with the perfect host: Hilton Avisford Park. With our exclusive hospitality package, fine dining and quality entertainment, you’re sure to please everyone. We’re renowned for being able to throw a great What does your perfect celebration look like? A full party. We take care of everything – from the party on feast with all the traditional trimmings and preparation to the little things that make it extra entertainment? special. We’re experts at bringing it all together, so From the simple and straightforward to the bespoke you can simply relax and enjoy. and bold, there’s nothing our team can’t make happen. IT'S TIME TO CFor thee ultlimeateb fesrtivea celtebraetion, we have a range of flexible party packages to suit you. Festive Lunches From £22.00 per person Christmas Day Lunch There’s nothing quite like getting the family around £89.00 per adult, children £45.00 per child a table and celebrating. We’ve some great The traditional Christmas meal can be a real labour packages to fit the most festive of gatherings, of love. At the Cedar Restaurant we'll happily take leaving you free to eat, drink and be merry. care of it all. So gather round a table full of delectable dishes. Festive Afternoon Tea From £20.00 per person For a little added indulgence, our festive themed NYE Gala Dinner £85.00 per person afternoon teas are elegantly presented with an Welcome 2019 in with style and join us for dinner, array of seasonal treats and delights. -

March 18, 2011

PI Week 11 March 12 - March 18, 2011 BBC Radio Ulster Celebrates St Patrick’s Day Programme Information New this week BBC Radio Ulster celebrates St Patrick’s Day with Horslips and the Ulster Orchestra Page 3 BBC Radio Ulster broadcasts live St Patrick’s Day concert with Horslips and the Ulster Orchestra from the Waterfront Hall BBC NI gears up for NW200 2011 Page 5 BBC Sport NI is gearing up for coverage of this year’s North West 200 International road races Jimmy Ellis At 80 Page 7 Gerry Anderson talks to actor James Ellis on BBC Radio Ulster as he celebrates his 80th birthday Bob Geldof special on The Late Show With Stuart Bailie Page 9 Bob Geldof talks to Stuart Bailie about his eventful career and life Calling Readers, Everywhere! Page 10 BBC Northern Ireland launches a new Book Group for local readers. In the third programme of the BBC Radio Ulster series In The Footsteps, on Sunday, March 13 at 1.30pm, journalist Fionala Meredith learns more about the twentieth century writer Helen Waddell, who won world wide acclaim with her study of the Medieval world in the 1920s and 30s but whose legacy is now largely forgotten. She is pictured here at Kilmacrew House with Helen Waddell’s great great niece and current custodian of the Kilmacrew and Helen Waddell estate, Louise Anson. Hugo Duncan will be bringing his BBC Radio Ulster show live from Mahon’s Hotel in Irvinestown, Co Fermanagh for a special St Patrick’s Day programme from 1.30pm-3pm on Thursday, March 17, when there’ll be plenty of craic, spe- cial country music guests and probably a cream bun or two.