Volume 9 Issue 3 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Constitutional Requirements for the Royal Morganatic Marriage

The Constitutional Requirements for the Royal Morganatic Marriage Benoît Pelletier* This article examines the constitutional Cet article analyse les implications implications, for Canada and the other members of the constitutionnelles, pour le Canada et les autres pays Commonwealth, of a morganatic marriage in the membres du Commonwealth, d’un mariage British royal family. The Germanic concept of morganatique au sein de la famille royale britannique. “morganatic marriage” refers to a legal union between Le concept de «mariage morganatique», d’origine a man of royal birth and a woman of lower status, with germanique, renvoie à une union légale entre un the condition that the wife does not assume a royal title homme de descendance royale et une femme de statut and any children are excluded from their father’s rank inférieur, à condition que cette dernière n’acquière pas or hereditary property. un titre royal, ou encore qu’aucun enfant issu de cette For such a union to be celebrated in the royal union n’accède au rang du père ni n’hérite de ses biens. family, the parliament of the United Kingdom would Afin qu’un tel mariage puisse être célébré dans la have to enact legislation. If such a law had the effect of famille royale, une loi doit être adoptée par le denying any children access to the throne, the laws of parlement du Royaume-Uni. Or si une telle loi devait succession would be altered, and according to the effectivement interdire l’accès au trône aux enfants du second paragraph of the preamble to the Statute of couple, les règles de succession seraient modifiées et il Westminster, the assent of the Canadian parliament and serait nécessaire, en vertu du deuxième paragraphe du the parliaments of the Commonwealth that recognize préambule du Statut de Westminster, d’obtenir le Queen Elizabeth II as their head of state would be consentement du Canada et des autres pays qui required. -

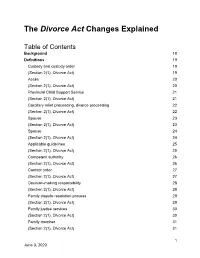

The Divorce Act Changes Explained

The Divorce Act Changes Explained Table of Contents Background 18 Definitions 19 Custody and custody order 19 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 19 Accès 20 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 20 Provincial Child Support Service 21 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 21 Corollary relief proceeding, divorce proceeding 22 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 22 Spouse 23 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 23 Spouse 24 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 24 Applicable guidelines 25 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 25 Competent authority 26 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 26 Contact order 27 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 27 Decision-making responsibility 28 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 28 Family dispute resolution process 29 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 29 Family justice services 30 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 30 Family member 31 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 31 1 June 3, 2020 Family violence 32 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 32 Legal adviser 35 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 35 Order assignee 36 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 36 Parenting order 37 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 37 Parenting time 38 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 38 Relocation 39 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 39 Jurisdiction 40 Two proceedings commenced on different days 40 (Sections 3(2), 4(2), 5(2) Divorce Act) 40 Two proceedings commenced on same day 43 (Sections 3(3), 4(3), 5(3) Divorce Act) 43 Transfer of proceeding if parenting order applied for 47 (Section 6(1) and (2) Divorce Act) 47 Jurisdiction – application for contact order 49 (Section 6.1(1), Divorce Act) 49 Jurisdiction — no pending variation proceeding 50 (Section 6.1(2), Divorce Act) -

Discover Canada the Rights and Responsibilities of Citizenship 2 Your Canadian Citizenship Study Guide

STUDY GUIDE Discover Canada The Rights and Responsibilities of Citizenship 2 Your Canadian Citizenship Study Guide Message to Our Readers The Oath of Citizenship Le serment de citoyenneté Welcome! It took courage to move to a new country. Your decision to apply for citizenship is Je jure (ou j’affirme solennellement) another big step. You are becoming part of a great tradition that was built by generations of pioneers I swear (or affirm) Que je serai fidèle before you. Once you have met all the legal requirements, we hope to welcome you as a new citizen with That I will be faithful Et porterai sincère allégeance all the rights and responsibilities of citizenship. And bear true allegiance à Sa Majesté la Reine Elizabeth Deux To Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second Reine du Canada Queen of Canada À ses héritiers et successeurs Her Heirs and Successors Que j’observerai fidèlement les lois du Canada And that I will faithfully observe Et que je remplirai loyalement mes obligations The laws of Canada de citoyen canadien. And fulfil my duties as a Canadian citizen. Understanding the Oath Canada has welcomed generations of newcomers Immigrants between the ages of 18 and 54 must to our shores to help us build a free, law-abiding have adequate knowledge of English or French In Canada, we profess our loyalty to a person who represents all Canadians and not to a document such and prosperous society. For 400 years, settlers in order to become Canadian citizens. You must as a constitution, a banner such as a flag, or a geopolitical entity such as a country. -

Alexander Manson Fonds (RBSC- ARC-1350)

University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections Finding Aid - Alexander Manson fonds (RBSC- ARC-1350) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.0 Printed: January 29, 2019 Language of description: English University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections Irving K. Barber Learning Centre 1961 East Mall Vancouver British Columbia V6T 1Z1 Telephone: 604-822-2521 Fax: 604-822-9587 Email: [email protected] http://rbsc.library.ubc.ca/ http://rbscarchives.library.ubc.ca//index.php/alexander-manson-fonds Alexander Manson fonds Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Physical -

The Purpose of C-6 Is to Create One Class of Canadian. Unless Amended, the Bill Will Not Achieve Its Objective

The purpose of C-6 is to create one class of Canadian. Unless amended, the Bill will not achieve its objective. Preamble: “A Canadian is a Canadian is a Canadian.” –Justin Trudeau, acceptance speech as Prime Minister, October 19, 2015. “We believe very strongly that there should be only one class of Canadians, that all Canadians are equal, that a Canadian is a Canadian is a Canadian from coast to coast to coast.” –John McCallum, Citizenship Minister, February 3, 2016. Fabulous words. Now let’s make it a reality. Bill C-6, as written, is but a start- it doesn’t get Canada to the Promised Land. If passed into law, unequal rights will continue, resulting in different classes of Canadian citizen- some with more rights than others. There will also be people denied citizenship altogether due to ongoing discrimination within the Act. My point in the following discussion is to exemplify the confusion and unjust legislation that bonds us together as Canadians. Trying to explain our current citizenship act is easy vs. deciding who under the law qualifies to call themselves Canadians, and why. For example, Canadian citizenship as we know it is an amalgamation of all the previous citizenship and immigration legislation going back more than 100 years. As such, the current Act is not a complete code for citizenship and nationality in that certain provisions of the 1947 Act must still be read as unrepealed. The authority for this is the Interpretation Act 1985 (44[h]), which specifies that provisions of a repealed Act must be read as unrepealed if those provisions are required to give effect to the Current Act. -

Translating the Constitution Act, 1867

TRANSLATING THE CONSTITUTION ACT, 1867 A Legal-Historical Perspective by HUGO YVON DENIS CHOQUETTE A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Law in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Laws Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September 2009 Copyright © Hugo Yvon Denis Choquette, 2009 Abstract Twenty-seven years after the adoption of the Constitution Act, 1982, the Constitution of Canada is still not officially bilingual in its entirety. A new translation of the unilingual Eng- lish texts was presented to the federal government by the Minister of Justice nearly twenty years ago, in 1990. These new French versions are the fruits of the labour of the French Constitutional Drafting Committee, which had been entrusted by the Minister with the translation of the texts listed in the Schedule to the Constitution Act, 1982 which are official in English only. These versions were never formally adopted. Among these new translations is that of the founding text of the Canadian federation, the Constitution Act, 1867. A look at this translation shows that the Committee chose to de- part from the textual tradition represented by the previous French versions of this text. In- deed, the Committee largely privileged the drafting of a text with a modern, clear, and con- cise style over faithfulness to the previous translations or even to the source text. This translation choice has important consequences. The text produced by the Commit- tee is open to two criticisms which a greater respect for the prior versions could have avoided. First, the new French text cannot claim the historical legitimacy of the English text, given their all-too-dissimilar origins. -

The Historical and Constitutional Context of the Proposed Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

THE HISTORICAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL CONTEXT OF THE PROPOSED CANADIAN CHARTER OF RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS WALTER S. TARNOPOLSKY* I INTRODUCTION As far back as 1967, when he was still Minister of Justice, Prime Minister Pierce Elliott Trudeau advocated changing the Canadian Bill of Rights by adop- tion of a constitutionally entrenched charter.' It should surprise no one, then, that just such a Charter of Rights and Freedoms constitutes the bulk of the proposed resolution which seeks one final amending Act by the United Kingdom Parliament of Canada's basic constitutional document-the British North America Act 2 (B.N.A. Act). The Charter of Rights and Freedoms possesses two qualities which radically distinguish it from its predecessor, the Canadian Bill of Rights. First, the Charter would be constitutionally entrenched. Endowed with constitutional authority, the rights and freedoms of the Charter would be superior to infringing legislation, which has not been exempted by means of a specifically enacted "notwithstand- ing" clause provided for in section 33 of the Charter, and subject to amendment only as a constitutional provision. Second, the Charter would apply equally to the provincial and Canadian federal governments. The purpose of this article is to provide the historical and constitutional con- text of the proposed Charter. Surveying the development of the judicial interpre- tations of the B.N.A. Act and the Canadian Bill of Rights, this article will attempt to bring into focus the major points of departure between the Charter and the Bill of Rights. At the same time, it is hoped that the value of these qualities of the Charter will become apparent as fundamental principles necessary to protect the civil liberties of Canadian citizens. -

Supreme Court of Canada the Canadian Charter of Rights

SUPREME COURT OF CANADA THE CANADIAN CHARTER OF RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS AND CANADIAN SOCIETY Michel Bastarache, Supreme Court of Canada Zaragosa, Spain, June 7, 2007 I have been asked to speak about the important changes in Canadian society that were brought about by the adoption of the Canada Act of 1982. The amendment to the Constitution of that year is best known for adopting the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms,1 or more simply, the Charter. Put simply, the Charter is an entrenched bill of rights, which as its title suggests, guarantees certain fundamental rights and freedoms to citizens and individuals. Its purpose is to prevent government, which in Canada includes the federal and provincial governments, from passing laws or acting in ways that violate those rights in a manner that cannot be justified in a free and democratic society. When a government does enact a law that unjustifiably violates one of the guarantees in the Charter, for example, by prohibiting public servants from speaking out in favour of a particular political party or a particular candidate,2 the courts have the power, and indeed the constitutional responsibility, to strike down the legislation. Similarly, when agents of the state, such as police officers, carry out unreasonable searches or seizures or when the law provides for cruel and unusual treatment or punishment on an individual, that individual is entitled to a remedy under the Charter. 1 Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (U.K.), c.11. 2 Osborne v. Canada (Treasury Board), [1991] 2 S.C.R. -

The Meaning of Canadian Federalism in Québec: Critical Reflections

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert The Meaning of Canadian federalisM in QuébeC: CriTiCal refleCTions guy laforest Professor of Political Science at the Laval University, Québec SUMMARY: 1. Introdution. – 2. Interpretive context. – 3. Contemporary trends and scholarship, critical reflections. – Conclusion. – Bibliography. – Abstract-Resum-Re- sumen. 1. Introduction As a teacher, in my instructions to students as they prepare their term papers, I often remind them that they should never abdicate their judgment to the authority of one single source. In the worst of circum- stances, it is much better to articulate one’s own ideas and convictions than to surrender to one single book or article. In the same spirit, I would urge readers not to rely solely on my pronouncements about the meaning of federalism in Québec. In truth, the title of this essay should include a question mark, and its content will illustrate, I hope, the richness and diversity of current Québec thinking on the subject. There are many ways as well to approach the topic at hand. The path I shall choose will reflect my academic identity: I am a political theorist and an intellectual historian, keenly interested about the relationship between philosophy and constitutional law in Canada, hidden in a political science department. As a reader of Gadamer and a former student of Charles Taylor, I shall start with some interpretive or herme- neutical precautions. Beyond the undeniable relevance of current re- flections about the theory of federalism in its most general aspects, the real question of this essay deals with the contemporary meaning of Canadian federalism in Québec. -

COVID's Collateral Contagion

June 2020 COVID’s Collateral Contagion: Why Faking Parliament is No Way to Govern in a Crisis Christian Leuprecht The COVID-19 epidemic is the greatest test for the maintenance of Canada’s democratic constitutional order in at least 50 years, certainly since the October crisis of 1970. It is also a bellwether for the way the Canadian state manages risk. Risks that stem from globalization have a common denominator: by definition, no state can manage them alone. However, citizens still expect their state to act. Confronted with dire predictions of immi- nent Armageddon, politicians invoke largely performative measures to signal to citizens that they are acting – to manage a risk that is largely beyond their control. Managing risk has become to individual citizens the essence of the modern welfare state: unemployment insur- ance, health care insurance, mortgage insurance, etc. Such is the essence of “risk society”: the expectations by citizens that the state will manage risks, many of which the state cannot control, such as a global pandemic. Paradoxically, the less control and certainty the state has over a risk that is perceived as existential, the more heavy-handed is its approach. Precisely because of the threatening environment in which it exists and because it is shut out of many international organizations, Taiwan was well prepared for the pandemic and its reaction was measured. By contrast, much of the rest of the democratic world was ill-prepared, which explains the heavy-handed measures taken by many of these countries, including Canada. The author of this document has worked independently and is solely responsible for the views presented here. -

No Brexit-Type Vote for Canada We Have the Clarity Act

For Immediate Release July 1, 2016 ARTICLE / PRESS RELEASE No Brexit-Type Vote For Canada We Have The Clarity Act Bill C-20, passed by the Parliament of Canada in the late 1990’s, otherwise known as the ‘Clarity Act’, ensures that all Canadians are fairly and democratically represented by a way of a “clear expression of a will by a clear majority of the population.” While the bill was drafted in response to the less-than-clear Quebec referendum question in both 1980 and 1995, it applies to all provinces. The Clarity Act is an integral component of our federalist system and seeks to protect Canadians from an underrepresented and unclear referendum question. I had the distinct honour as Deputy Unity Critic under Leader Preston Manning to strongly martial Reform Party Support for acceptance. The Clarity Act served to balance the pre-requisite of all societal organizations and constitutions that call for 66% (or two-thirds) of voter support for substantive changes that diametrically impact all members (read citizens) existing rights and those that wish for only 50% + 1 for change, because these changes will be difficult to reverse when enacted. The Clarity Act cites over 10 times that approval for referendum must be determined by a clear expression by a clear majority of the population eligible to vote. This means that a majority of all eligible voters must be considered, not just those who show up at the polls to vote. Furthermore, the Supreme Court of Canada, agreeing with Bill C-20, specifies that any proposal relating to the constitutional makeup of a democratic state is a matter of utmost gravity and is of fundamental importance to all of its citizens. -

The 1992 Charlottetown Accord & Referendum

CANADA’S 1992 CHARLOTTETOWN CONSTITUTIONAL ACCORD: TESTING THE LIMITS OF ASYMMETRICAL FEDERALISM By Michael d. Behiels Department of History University of Ottawa Abstract.-Canada‘s 1992 Charlottetown Constitutional Accord represented a dramatic attempt to transform the Canadian federation which is based on formal symmetry, albeit with a limited recognition of some asymmetry, into an asymmetrical federal constitution recognizing Canada‘s three nations, French, British, and Aboriginal. Canadians were called up to embrace multinational federalism, one comprising both stateless and state-based nations exercising self-governance in a multilayered, highly asymmetrical federal system. This paper explores why a majority of Canadians, for a wide variety of very complex reasons, opted in the first-ever constitutional referendum in October 1992 to retain their existing federal system. This paper argues that the rejection of a formalized asymmetrical federation based on the theory of multinational federalism, while contributing to the severe political crisis that fueled the 1995 referendum on Quebec secession, marked the moment when Canadians finally became a fully sovereign people. Palacio de la Aljafería – Calle de los Diputados, s/n– 50004 ZARAGOZA Teléfono 976 28 97 15 - Fax 976 28 96 65 [email protected] INTRODUCTION The Charlottetown Consensus Report, rejected in a landmark constitutional referendum on 26 October 1992, entailed a profound clash between competing models of federalism: symmetrical versus asymmetrical, and bi-national versus multinational. (Cook, 1994, Appendix, 225-249) The Meech Lake Constitutional Accord, 1987-90, pitted two conceptions of a bi-national -- French-Canada and English Canada – federalism against one another. The established conception entailing a pan-Canadian French-English duality was challenged and overtaken by a territorial Quebec/Canada conception of duality.