Compassion Beyond Boundaries, Solidarity Beyond Beliefs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish Non-Governmental Organizations

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Faculty Publications Department of English 2011 Jewish Non-governmental Organizations Michael Galchinsky Georgia State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_facpub Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Galchinsky, M. (2011). Jewish Non-governmental Organizations. In Thomas Cushman (Ed.), Routledge Handbook of Human Rights (pp. 560-569). New York: Routledge. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Michael Galchinsky Jewish Non-governmental Organizations Human rights history and Jewish history have been inextricably intertwined. The history of Jews’ persecution as an ethnic and religious minority, especially the Nazis’ systematic deprivation of Jews’ rights, became a standard reference for postwar activists after 1945 who argued for a global system limiting states’ power over their citizens. Many Jewish activists saw a commitment to international human rights as the natural outgrowth of traditional Jewish values. Jews could be especially active in advocating for universal rights protections not only because their suffering conferred moral standing on their cause but also because they could plumb a rich religious and philosophical tradition to find support for a cosmopolitan worldview and because they nurtured generations of experienced organizers. Jews did not always seek, find, or emphasize the universalism in their tradition. -

Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements

Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Alan Robert Lopez Chiang Mai , Thailand ISBN 978-1-137-54349-3 ISBN 978-1-137-54086-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-54086-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016956808 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Cover image © Nickolay Khoroshkov / Alamy Stock Photo Printed on acid-free paper This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Nature America Inc. -

Promoting Widespread Awareness of Religious Rights Through Print and Online Media in Near Eastern, South Asian and East Asian C

Promoting Widespread Awareness of Religious Rights through Print and Online Media in Near Eastern, South Asian and East Asian Countries – Appendix A: Articles and Reprint Information Below is a comprehensive list of articles produced under this grant, their authors and dates of their distribution, as well as links to the full articles online and the news outlets that distributed them. 1. “The power of face-to-face encounters between Israelis and Palestinians” (July 5, 2011) by Yonatan Gur. Reprints: 18 In English In French Today's Zaman (Turkey) Pretty Zoelly‟s Blog (blog) (France) Inter Religious Encounter Information Consultancy Human Dignity and Humiliation Studies (US) In Indonesian The Global Human, (blog) (US) Mulyanis (blog) (Indonesia) Facebook (Adam Waddell) (Israel) Peace Please (US) In Urdu The) Jewish Reporter (US) Al Qamar (Islamabad) (Pakistan) The Daily News Egypt (Egypt) Masress.com (Egypt) Bali Times (Indonesia) The Positive Universe (US) Fuse.tv (US) Facebook (T-Cells (Transformative Cells)) (US) Facebook (United Religions Initiative) (US) Occupation Magazine 2. “In Lebanon, dialogue as a solution” (June 28, 2011) by Hani Fahs. Reprints: 17 In English In Arabic Canadian Lebanese Human Rights Federation Al Wasat News (Bahrain) Religie(Canada) 24 (Netherlands) Hitteen News (Jordan) Taif News (Saudi Arabia) Gulf Daily News (Bahrain) Middle East Online (UK) Schema-root.org (US) In French Kentucky Country Day School (KCD) (US) Al Balad (Lebanon) Peace Please (US) Facebook (Journal of Inter-Religious Dialogue) In Indonesian Khaleej Times (UAE) Mulyanis (blog) (Indonesia) Al Arabiya (UAE) Rima News.com (Indonesia) Facebook (Journal of Inter-Religious Dialogue) In Urdu Angola | Burundi | Côte d'Ivoire | Democratic Republic of Congo | Guinea | Indonesia | Jerusalem | Kenya Kosovo | Lebanon | Liberia | Macedonia | Morocco | Nepal | Nigeria | Pakistan | Rwanda | Sierra Leone Sudan | Timor-Leste | Ukraine | USA | Yemen | Zimbabwe Al Qamar (Islamabad) (Pakistan) 3. -

Buddhist Bibio

Recommended Books Revised March 30, 2013 The books listed below represent a small selection of some of the key texts in each category. The name(s) provided below each title designate either the primary author, editor, or translator. Introductions Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction Damien Keown Taking the Path of Zen !!!!!!!! Robert Aitken Everyday Zen !!!!!!!!! Charlotte Joko Beck Start Where You Are !!!!!!!! Pema Chodron The Eight Gates of Zen !!!!!!!! John Daido Loori Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind !!!!!!! Shunryu Suzuki Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening ! Stephen Batchelor The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation!!!!!!!!! Thich Nhat Hanh Buddhism For Beginners !!!!!!! Thubten Chodron The Buddha and His Teachings !!!!!! Sherab Chödzin Kohn and Samuel Bercholz The Spirit of the Buddha !!!!!!! Martine Batchelor 1 Meditation and Zen Practice Mindfulness in Plain English ! ! ! ! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English !!! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana Change Your Mind: A Practical Guide to Buddhist Meditation ! Paramananda Making Space: Creating a Home Meditation Practice !!!! Thich Nhat Hanh The Heart of Buddhist Meditation !!!!!! Thera Nyanaponika Meditation for Beginners !!!!!!! Jack Kornfield Being Nobody, Going Nowhere: Meditations on the Buddhist Path !! Ayya Khema The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation Thich Nhat Hanh Zen Meditation in Plain English !!!!!!! John Daishin Buksbazen and Peter -

Taiwan's Tzu Chi As Engaged Buddhism

BSRV 30.1 (2013) 137–139 Buddhist Studies Review ISSN (print) 0256-2897 doi: 10.1558/bsrv.v30i1.137 Buddhist Studies Review ISSN (online) 1747-9681 Taiwan’s Tzu Chi as Engaged Buddhism: Origins, Organization, Appeal and Social Impact, by Yu-Shuang Yao. Global Oriental, Brill, 2012. 243pp., hb., £59.09/65€/$90, ISBN-13: 9789004217478. Reviewed by Ann Heirman, Oriental Languages and Cultures, Ghent University, Belgium. Keywords Tzu Chi, Taiwanese Buddhism, Engaged Buddhism Taiwan’s Tzu Chi as Engaged Buddhism is a well-written book that addresses a most interesting topic in Taiwanese Buddhism, namely the way in which Engaged Buddhism found its way into Taiwan in, and through, the Tzu Chi Foundation (the Buddhist Compassion Relief Tzu Chi Foundation). Founded in 1966, the Foundation expanded in the 1990s, and so became the largest lay organiza- tion in a contemporary Chinese context. The overwhelming involvement of the laity introduced a new aspect, and has triggered major changes in Taiwanese Buddhism. The present book offers a most welcome comprehensive study of the Foundation, discussing its context, development, structure, teaching and prac- tices. With its focus on both the history and the social context, the work devel- ops an interesting interdisciplinary approach, offering valuable insights into the appeal of the movement to a Taiwanese public. Nevertheless, some remarks still need to be made. The work is based on research that was completed in 2001, and research updates have not been pro- duced since, apart from a small Afterword (pp. 228-230). Yet not publishing the present work would have been a loss to the scientific community. -

Convened by the Peace Council and the Center for Health and Social

CHSP_Report_cover.qxd Printer: Please adjust spine width if necessary. Additional copies of this report may be obtained from: ............................................................................................................. ............................................................................................................. International Committee for the Peace Council The Center for Health and Social Policy 2702 International Lane, Suite 108 847 25th Avenue Convened by The Peace Council and The Center for Health and Social Policy Madison, WI 53704 San Francisco, CA 94121 United States United States Chiang Mai, Thailand 1-608-241-2200 Phone 1-415-386-3260 Phone February 29–March 3, 2004 1-608-241-2209 Fax 1-415-386-1535 Fax [email protected] [email protected] www.peacecouncil.org www.chsp.org ............................................................................................................. Copyright © 2004 by The Center for Health and Social Policy and The Peace Council ............................................................................................................. Convened by The Peace Council and The Center for Health and Social Policy Chiang Mai, Thailand February 29–March 3, 2004 Contents Introduction 5 Stephen L. Isaacs and Daniel Gómez-Ibáñez The Chiang Mai Declaration: 9 Religion and Women: An Agenda for Change List of Participants 13 Background Documents World Religions on Women: Their Roles in the Family, 19 Society, and Religion Christine E. Gudorf Women and Religion in the Context of Globalization 49 Vandana Shiva World Religions and the 1994 United Nations 73 International Conference on Population and Development A Report on an International and Interfaith Consultation, Genval, Belgium, May 4-7, 1994 3 Introduction Stephen L. Isaacs and Daniel Gómez-Ibáñez Forty-eight religious and women’s leaders participated in a “conversation” in Chi- ang Mai, Thailand between February 29 and March 3, 2004 to discuss how, in an era of globalization, religions could play a more active role in advancing women’s lives. -

Bridging Worlds: Buddhist Women's Voices Across Generations

BRIDGING WORLDS Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo First Edition: Yuan Chuan Press 2004 Second Edition: Sakyadhita 2018 Copyright © 2018 Karma Lekshe Tsomo All rights reserved No part of this book may not be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage or retreival system, without the prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations. Cover Illustration, "Woman on Bridge" © 1982 Shig Hiu Wan. All rights reserved. "Buddha" calligraphy ©1978 Il Ta Sunim. All rights reserved. Chapter Illustrations © 2012 Dr. Helen H. Hu. All rights reserved. Book design and layout by Lillian Barnes Bridging Worlds Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo 7th Sakyadhita International Conference on Buddhist Women With a Message from His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama SAKYADHITA | HONOLULU, HAWAI‘I iv | Bridging Worlds Contents | v CONTENTS MESSAGE His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xiii INTRODUCTION 1 Karma Lekshe Tsomo UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN AROUND THE WORLD Thus Have I Heard: The Emerging Female Voice in Buddhism Tenzin Palmo 21 Sakyadhita: Empowering the Daughters of the Buddha Thea Mohr 27 Buddhist Women of Bhutan Tenzin Dadon (Sonam Wangmo) 43 Buddhist Laywomen of Nepal Nivedita Kumari Mishra 45 Himalayan Buddhist Nuns Pacha Lobzang Chhodon 59 Great Women Practitioners of Buddhadharma: Inspiration in Modern Times Sherab Sangmo 63 Buddhist Nuns of Vietnam Thich Nu Dien Van Hue 67 A Survey of the Bhikkhunī Saṅgha in Vietnam Thich Nu Dong Anh (Nguyen Thi Kim Loan) 71 Nuns of the Mendicant Tradition in Vietnam Thich Nu Tri Lien (Nguyen Thi Tuyet) 77 vi | Bridging Worlds UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN OF TAIWAN Buddhist Women in Taiwan Chuandao Shih 85 A Perspective on Buddhist Women in Taiwan Yikong Shi 91 The Inspiration ofVen. -

Conditions and Challenges Experienced by Human Rights Defenders in Carrying out Their Work

Conditions and challenges experienced by human rights defenders in carrying out their work: Findings and recommendations of a fact-finding mission to Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories carried out by Forefront and by the World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) and the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) in their joint programme the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders Table of contents Paragraphs Executive Summary A. Mission’s rationale and objectives 1-4 B. The delegation’s composition and activities • Composition 5 • Programme 6-12 • Working methods 13-14 C. The environment in which human rights NGOs operate • Upholding human rights in a context of armed conflict and terrorism 15-23 • Freedom of association: Issues relating to human rights NGO’s registration and funding 24-34 • Freedom of expression of human rights defenders 35-37 • Restrictions on freedom of movement affecting the work of human rights NGOs 38-43 • Conditions experienced by the international human rights organisations 44-46 • The NGOs section of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the State of Israel 47-50 D. Main issues that human rights NGOs address • Upholding international humanitarian law in a context of occupation 51-55 • Protecting persons in administrative detention and opposing any forms of torture and ill-treatment 56-61 • Upholding the right to defence and due process of law 62-70 • Opposing house demolitions in the OPTs as collective punishment and ill-treatment 71-72 • Fighting for the dismantlement of Israeli settlements and opposing land-seizure in the OPTs 73-75 E. Specific risks to which human rights defenders are exposed • Physical risks and security hazards faced by human rights defenders in Israel and the OPTs 76-77 • Detention and ill-treatment of human rights defenders: The case of Mr. -

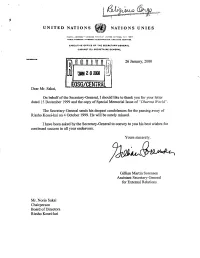

EOSG/CENTRAL Dear Mr

UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES POSTAL ADDRESS ADRESSE POST ALE- UNITED NATIONS, N.V. 1OO17 CABLE AODflCSS ADRESSE TELEGRAPHIQUE: I/NATIONS NEWYORK EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL CABINET OU SECRETAIRE GENERAL REFERENCE: 26 January, 2000 EOSG/CENTRAL Dear Mr. Sakai, On behalf of the Secretary-General, I should like to thank you for your letter dated 15 December 1999 and the copy of Special Memorial Issue of "Dharma World". The Secretary-General sends his deepest condolences for the passing away of Rissho Kosei-kai on 4 October 1999. He will be surely missed. I have been asked by the Secretary-General to convey to you his best wishes for continued success hi all your endeavors. Yours sincerely, Gillian Martin Sorensen Assistant Secretary-General for External Relations Mr. Norio Sakai Chairperson Board of Directors Rissho Kosei-kai RISSHO KOSEI-KAI C, A BUDDHIST ORGANIZATION 2-11-1 Wada, Suginami-ku, Tokyo 166-8537, Japan, Tel: 03-3383-1111 lilJLU DEC 2 9 I999 December 15, 1999 Dear Sir/Madam, Special Memorial Issue of Dharrna World I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude for your friendship with Rissho Kosei-kai. As you may know, Founder Nikkyo Niwano peacefully passed away on October 4, 1999 at the age of 92. The enclosed Special Memorial Issue of Dharma World carries full details of the Founder's funeral ceremonies and a complete review of his life and work. I am very pleased to present this issue to you as a token of our wholehearted appreciation. Founder's posthumous name is "If^JLEIifc—SfbfcfiirlJ" (Kaiso Nikkyo Ichijo Daishi) in Japanese and "The Founder Nikkyo, Great Teacher of the One Vehicle" in English. -

From Bishop Munib Younan Easter Message from the Holy Land

Easter Message from the Holy Land From Bishop Munib Younan Easter Message from the Holy Land Salaam and Grace in the name of our Crucified and Risen Lord, Jesus Christ. As I write this message of Easter, I really do not know where to start, lest somebody will ask me: What is the truth? It seems that the truth lies beyond the thoughts of our hearts and beyond the mass media. When Jesus was indicted on Maundy Thursday, the truth lay in that he was the Messiah, the Lamb of God, who came to carry the sin of the world. Here many incidents take place everyday. It is in every minute that things change. The situation is very unpredictable. The other day, I visited Hebron with Peter Prove (Lutheran World Federation), Kent Johnson (ELCA), and Gustaf Odquist, where we were generously hosted by one of the Moslem Sheiks, who is a close friend of mine. We were shocked to see the real picture of the truth. An Israeli settler woman was throwing stones on Palestinian shopkeepers while the army was leniently asking her not to do so. At the same time, other soldiers nearby were shooting live ammunition on Palestinian youth. I ask: What is the truth? Is this justice? Where is at least the Christian conscience? The situation continues to deteriorate day by day. The Israeli siege on the Palestinian territories is tightening. You need only to pass in the morning near my house in Tantur and watch the police and soldiers running after Palestinian laborers, who search for their daily bread, and witness the realities behind the UN statistics stating that the present unemployment rate in the Palestinian areas is now around 38% of the working force. -

Religion in the Age of Development

religions Article Religion in the Age of Development R. Michael Feener 1,* and Philip Fountain 2 1 Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies, Marston Road, Oxford OX3 0EE, UK 2 Religious Studies, Victoria University of Wellington, PO Box 600, Wellington 6140, New Zealand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 October 2018; Accepted: 20 November 2018; Published: 23 November 2018 Abstract: Religion has been profoundly reconfigured in the age of development. Over the past half century, we can trace broad transformations in the understandings and experiences of religion across traditions in communities in many parts of the world. In this paper, we delineate some of the specific ways in which ‘religion’ and ‘development’ interact and mutually inform each other with reference to case studies from Buddhist Thailand and Muslim Indonesia. These non-Christian cases from traditions outside contexts of major western nations provide windows on a complex, global history that considerably complicates what have come to be established narratives privileging the agency of major institutional players in the United States and the United Kingdom. In this way we seek to move discussions toward more conceptual and comparative reflections that can facilitate better understandings of the implications of contemporary entanglements of religion and development. Keywords: Religion; Development; Humanitarianism; Buddhism; Islam; Southeast Asia A Sarvodaya Shramadana work camp has proved to be the most effective means of destroying the inertia of any moribund village community and of evoking appreciation of its own inherent strength and directing it towards the objective of improving its own conditions. A.T. -

Progressive Action Guide

Activist Guide Progressive Action for Human Rights, Peace & Reconciliation in Israel and Palestine Prepared as part of TTN’s Boston & New England Initiative for Progressive Academic Engagement with Israel and Palestine The Third Narrative (TTN) is an initiative of Ameinu 424 West 33rd Street, Suite 150 New York, NY 10001 212-366-1194 Table of contents Introduction 2 Menu of Activist Tactics 3 Advocacy & Political Action in the U.S. Direct Action / Volunteering in Israel and Palestine Investment in a Palestinian State 4 Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Education Cultural & Academic Exchange 5 Activist Resources 6 Anti-Occupation Activists: Israel and Palestine Anti-Occupation Activists: North America 8 Coexistence & Dialogue 9 Environmental Initiatives 13 Human Rights 14 Israeli Arab Empowerment and Equality 15 Economic Development Health Initiatives 16 Think Tanks – Public Policy 17 Appendix: Educational Travel in Israel and Palestine 18 1 Introduction If you are pro-Palestinian and pro-Israeli and would like to help promote two states, human rights and social justice in Palestine and Israel, this guide is for you. It is meant primarily for North American progressives in colleges and universities, but we believe people in unions, religious organizations and other groups will also find it useful. Currently, one question that is hotly debated on many campuses is whether or not to support the BDS (boycott, divestment, sanctions) movement targeting Israel. Often, this conversation diverts attention from a wide range of other political options aimed at ending the Israeli occupation, building a viable Palestinian state, protecting human rights and fostering reconciliation between Jews and Arabs. We have prepared this guide to describe and promote those options.