Jewish Non-Governmental Organizations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promoting Widespread Awareness of Religious Rights Through Print and Online Media in Near Eastern, South Asian and East Asian C

Promoting Widespread Awareness of Religious Rights through Print and Online Media in Near Eastern, South Asian and East Asian Countries – Appendix A: Articles and Reprint Information Below is a comprehensive list of articles produced under this grant, their authors and dates of their distribution, as well as links to the full articles online and the news outlets that distributed them. 1. “The power of face-to-face encounters between Israelis and Palestinians” (July 5, 2011) by Yonatan Gur. Reprints: 18 In English In French Today's Zaman (Turkey) Pretty Zoelly‟s Blog (blog) (France) Inter Religious Encounter Information Consultancy Human Dignity and Humiliation Studies (US) In Indonesian The Global Human, (blog) (US) Mulyanis (blog) (Indonesia) Facebook (Adam Waddell) (Israel) Peace Please (US) In Urdu The) Jewish Reporter (US) Al Qamar (Islamabad) (Pakistan) The Daily News Egypt (Egypt) Masress.com (Egypt) Bali Times (Indonesia) The Positive Universe (US) Fuse.tv (US) Facebook (T-Cells (Transformative Cells)) (US) Facebook (United Religions Initiative) (US) Occupation Magazine 2. “In Lebanon, dialogue as a solution” (June 28, 2011) by Hani Fahs. Reprints: 17 In English In Arabic Canadian Lebanese Human Rights Federation Al Wasat News (Bahrain) Religie(Canada) 24 (Netherlands) Hitteen News (Jordan) Taif News (Saudi Arabia) Gulf Daily News (Bahrain) Middle East Online (UK) Schema-root.org (US) In French Kentucky Country Day School (KCD) (US) Al Balad (Lebanon) Peace Please (US) Facebook (Journal of Inter-Religious Dialogue) In Indonesian Khaleej Times (UAE) Mulyanis (blog) (Indonesia) Al Arabiya (UAE) Rima News.com (Indonesia) Facebook (Journal of Inter-Religious Dialogue) In Urdu Angola | Burundi | Côte d'Ivoire | Democratic Republic of Congo | Guinea | Indonesia | Jerusalem | Kenya Kosovo | Lebanon | Liberia | Macedonia | Morocco | Nepal | Nigeria | Pakistan | Rwanda | Sierra Leone Sudan | Timor-Leste | Ukraine | USA | Yemen | Zimbabwe Al Qamar (Islamabad) (Pakistan) 3. -

Convened by the Peace Council and the Center for Health and Social

CHSP_Report_cover.qxd Printer: Please adjust spine width if necessary. Additional copies of this report may be obtained from: ............................................................................................................. ............................................................................................................. International Committee for the Peace Council The Center for Health and Social Policy 2702 International Lane, Suite 108 847 25th Avenue Convened by The Peace Council and The Center for Health and Social Policy Madison, WI 53704 San Francisco, CA 94121 United States United States Chiang Mai, Thailand 1-608-241-2200 Phone 1-415-386-3260 Phone February 29–March 3, 2004 1-608-241-2209 Fax 1-415-386-1535 Fax [email protected] [email protected] www.peacecouncil.org www.chsp.org ............................................................................................................. Copyright © 2004 by The Center for Health and Social Policy and The Peace Council ............................................................................................................. Convened by The Peace Council and The Center for Health and Social Policy Chiang Mai, Thailand February 29–March 3, 2004 Contents Introduction 5 Stephen L. Isaacs and Daniel Gómez-Ibáñez The Chiang Mai Declaration: 9 Religion and Women: An Agenda for Change List of Participants 13 Background Documents World Religions on Women: Their Roles in the Family, 19 Society, and Religion Christine E. Gudorf Women and Religion in the Context of Globalization 49 Vandana Shiva World Religions and the 1994 United Nations 73 International Conference on Population and Development A Report on an International and Interfaith Consultation, Genval, Belgium, May 4-7, 1994 3 Introduction Stephen L. Isaacs and Daniel Gómez-Ibáñez Forty-eight religious and women’s leaders participated in a “conversation” in Chi- ang Mai, Thailand between February 29 and March 3, 2004 to discuss how, in an era of globalization, religions could play a more active role in advancing women’s lives. -

Conditions and Challenges Experienced by Human Rights Defenders in Carrying out Their Work

Conditions and challenges experienced by human rights defenders in carrying out their work: Findings and recommendations of a fact-finding mission to Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories carried out by Forefront and by the World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) and the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) in their joint programme the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders Table of contents Paragraphs Executive Summary A. Mission’s rationale and objectives 1-4 B. The delegation’s composition and activities • Composition 5 • Programme 6-12 • Working methods 13-14 C. The environment in which human rights NGOs operate • Upholding human rights in a context of armed conflict and terrorism 15-23 • Freedom of association: Issues relating to human rights NGO’s registration and funding 24-34 • Freedom of expression of human rights defenders 35-37 • Restrictions on freedom of movement affecting the work of human rights NGOs 38-43 • Conditions experienced by the international human rights organisations 44-46 • The NGOs section of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the State of Israel 47-50 D. Main issues that human rights NGOs address • Upholding international humanitarian law in a context of occupation 51-55 • Protecting persons in administrative detention and opposing any forms of torture and ill-treatment 56-61 • Upholding the right to defence and due process of law 62-70 • Opposing house demolitions in the OPTs as collective punishment and ill-treatment 71-72 • Fighting for the dismantlement of Israeli settlements and opposing land-seizure in the OPTs 73-75 E. Specific risks to which human rights defenders are exposed • Physical risks and security hazards faced by human rights defenders in Israel and the OPTs 76-77 • Detention and ill-treatment of human rights defenders: The case of Mr. -

From Bishop Munib Younan Easter Message from the Holy Land

Easter Message from the Holy Land From Bishop Munib Younan Easter Message from the Holy Land Salaam and Grace in the name of our Crucified and Risen Lord, Jesus Christ. As I write this message of Easter, I really do not know where to start, lest somebody will ask me: What is the truth? It seems that the truth lies beyond the thoughts of our hearts and beyond the mass media. When Jesus was indicted on Maundy Thursday, the truth lay in that he was the Messiah, the Lamb of God, who came to carry the sin of the world. Here many incidents take place everyday. It is in every minute that things change. The situation is very unpredictable. The other day, I visited Hebron with Peter Prove (Lutheran World Federation), Kent Johnson (ELCA), and Gustaf Odquist, where we were generously hosted by one of the Moslem Sheiks, who is a close friend of mine. We were shocked to see the real picture of the truth. An Israeli settler woman was throwing stones on Palestinian shopkeepers while the army was leniently asking her not to do so. At the same time, other soldiers nearby were shooting live ammunition on Palestinian youth. I ask: What is the truth? Is this justice? Where is at least the Christian conscience? The situation continues to deteriorate day by day. The Israeli siege on the Palestinian territories is tightening. You need only to pass in the morning near my house in Tantur and watch the police and soldiers running after Palestinian laborers, who search for their daily bread, and witness the realities behind the UN statistics stating that the present unemployment rate in the Palestinian areas is now around 38% of the working force. -

Progressive Action Guide

Activist Guide Progressive Action for Human Rights, Peace & Reconciliation in Israel and Palestine Prepared as part of TTN’s Boston & New England Initiative for Progressive Academic Engagement with Israel and Palestine The Third Narrative (TTN) is an initiative of Ameinu 424 West 33rd Street, Suite 150 New York, NY 10001 212-366-1194 Table of contents Introduction 2 Menu of Activist Tactics 3 Advocacy & Political Action in the U.S. Direct Action / Volunteering in Israel and Palestine Investment in a Palestinian State 4 Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Education Cultural & Academic Exchange 5 Activist Resources 6 Anti-Occupation Activists: Israel and Palestine Anti-Occupation Activists: North America 8 Coexistence & Dialogue 9 Environmental Initiatives 13 Human Rights 14 Israeli Arab Empowerment and Equality 15 Economic Development Health Initiatives 16 Think Tanks – Public Policy 17 Appendix: Educational Travel in Israel and Palestine 18 1 Introduction If you are pro-Palestinian and pro-Israeli and would like to help promote two states, human rights and social justice in Palestine and Israel, this guide is for you. It is meant primarily for North American progressives in colleges and universities, but we believe people in unions, religious organizations and other groups will also find it useful. Currently, one question that is hotly debated on many campuses is whether or not to support the BDS (boycott, divestment, sanctions) movement targeting Israel. Often, this conversation diverts attention from a wide range of other political options aimed at ending the Israeli occupation, building a viable Palestinian state, protecting human rights and fostering reconciliation between Jews and Arabs. We have prepared this guide to describe and promote those options. -

On the Significance of Religion in Conflict and Conflict Resolution

91 8 JEWISH PERSPECTIVE RELIGION IN ISRAEL’S QUEST FOR CONFLICT RESOLUTION AND RECONCILIATION IN ITS LAND RIGHTS CONFLICTS Pauline Kollontai INTRODUCTION: POLITICAL APPROACHES TO RESOLVING LAND CONFLICTS Seventy- one years on from its establishment, Israel continues to be in conflict over land with the Negev Bedouin and the Palestinians. During these past seven decades there have been signs of a reduction in the level and intensity of these conflicts. In the case of the Negev Bedouin, the first serious attempt at addressing this issue was seen in the work of the Goldberg Commission, set up by the Israeli govern- ment in 2007 during the Prime Ministership of Ehud Olmet. The Goldberg Commission, chaired by retired Supreme Court Justice, Eliezer Goldberg, had eight members, including two Bedouin representatives. The starting point for Goldberg was to acknow- ledge that there had been a number of government committees tasked to propose further strategies for Negev Bedouin resettlement and to find a compromise over land, “Most of these committees have had no serious impact on the issues they were set up to deal with” (Goldberg 2011: 22). At the beginning of the Commission’s Report it states that seeing the Bedouin as the “other” has to be changed, “The approach of ‘us’ and ‘them’ is not acceptable to us, and it will not advance a solution, but rather drive it further away” 92 93 92 RELIGION matters IN CONFLICT RESOLUTION (Goldberg 2011: 5). This approach is also a fundamental obstacle to resolving Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians. As of the time of writing (September 2019), there has been no significant improve- ment to the Negev Bedouin’s land struggle with the Israeli state. -

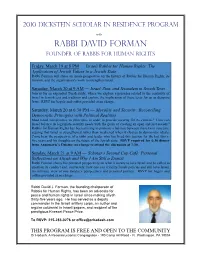

Rabbi David Forman

2010 Dickstein Scholar in Residence Program with RABBI DAVID FORMAN FOUNDER OF RABBIS FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Friday, March 19 at 8 PM — Israeli Rabbis for Human Rights: The Application of Jewish Values to a Jewish State Rabbi Forman will share an inside perspective on the history of Rabbis for Human Rights, its mission, and the organization’s work to strengthen Israel. Saturday, March 20 at 9 AM — Israel, Zion, and Jerusalem in Jewish Texts Join us for an expanded Torah study, where we explore a passages related to the centrality of Israel in Jewish text and tradition and explore the implication of these texts for us as diaspora Jews. RSVP for bagels and coffee provided at no charge. Saturday, March 20 at 6:30 PM — Morality and Security: Reconciling Democratic Principles with Political Realities Must Israel compromise its principles in order to provide security for its citizens? How can Israel balance its legitimate security needs with the goals of creating an open and just society? Rabbis for Human Rights has been striving to promote a balance between these twin concerns, arguing that Israel is strengthened rather than weakened when it cleaves to democratic ideals. Come hear the perspective of a rabbi and leader who has lived this tension for the last thirty- five years and his thoughts on the future of the Jewish state. RSVP required for 6:30 dinner from Annemarie’s Cuisine; no charge to attend the discussion at 7:30. Sunday, March 21 at 9 AM — Scholar’s Second Cup Café: Personal Reflections on Aliyah and Why I Am Still a Zionist Rabbi Forman shares his personal perspectives on what it means to love Israel and be called to question its conduct and, conversely, how one can criticize Israeli policies and still love Israel. -

Dabro Leshalom1: a Jewish Contemplation of Peacemaking Rabbi Edward Rettig2 American Jewish Committee, Israel/Middle East Office, Jerusalem

Studies in Christian-Jewish Relations Volume 2, Issue 2(2007): CP18-24 CONFERENCE PROCEEDING Dabro LeShalom1: A Jewish Contemplation of Peacemaking Rabbi Edward Rettig2 American Jewish Committee, Israel/Middle East Office, Jerusalem Delivered at From the Inside: A Look at the Issues Facing Israel Today, March 6, 2007 Sponsored by American Jewish Committee, Greater Boston Chapter True peace cannot come except by studying and understanding diverging views, knowing that they have their place, each according to its concerns. In the union of opposites do we behold the blessing of peace. – Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak Hacohen Kuk, Olat Re’aya 1:330-331 It has been hard of late to be a supporter of dialogue in this fractured Holy Land. The recent trend toward unilateralism in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is in large part an expression of disillusionment with dialogue. The "disengagement" or "convergence" plans and the electoral (and military) victories of the rejectionists such as Hamas are part of this despair. Many well- meaning groups on both sides of the conflict are now tempted as never before to abandon the path of peace through dialogue. However, for truly religious Jews, as for Christians and Muslims, despair is not an option. Among Jews, shalom – peace or tranquility – is at the heart of our religious identity. In the Midrash, a set of collections of rabbinic maxims redacted in the first several centuries of the Common Era, Rabbi Yudan son of Rabbi Yossi interprets the phrase, “And he called God, Peace!” (Jgs 6:24). Rabbi Yudan says: “Great is peace, since the name of the Holy One, Blessed be He, is called Peace.” In the world of the Sages, shalom is interwoven with Godliness. -

THE ROLE of RELIGION in CONFLICT and PEACE- BUILDING the British Academy Is the UK’S Independent National Academy Representing the Humanities and Social Sciences

THE ROLE OF RELIGION IN CONFLICT AND PEACE- BUILDING The British Academy is the UK’s independent national academy representing the humanities and social sciences. For over a century it has supported and celebrated the best in UK and international research and helped connect the expertise of those working in these disciplines with the wider public. The Academy supports innovative research and outstanding people, informs policy and seeks to raise the level of public engagement with some of the biggest issues of our time, through policy reports, publications and public events. The Academy represents the UK’s research excellence worldwide in a fast changing global environment. It promotes UK research in international arenas, fosters a global approach across UK research, and provides leadership in developing global links and expertise. www.britishacademy.ac.uk The Role of Religion in Conflict and Peacebuilding September 2015 THE BRITISH ACADEMY 10 –11 Carlton House Terrace London SW1Y 5AH www.britiahacademy.ac.uk Registered Charity: Number 233176 © The British Academy 2015 Published September 2015 ISBN 978-0-85672-618-7 Designed by Soapbox, www.soapbox.co.uk Printed by Team Contents Acknowledgements iv Abbreviations v About the authors vi Executive summary 1 1. Introduction 3 2. Definitions 5 3. Methodology 11 4. Literature review 14 5. Case study I: Religion and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict 46 6. Case study II: Mali 57 7. Case study III: Bosnia and Herzegovina 64 8. Conclusions 70 9. Recommendations for policymakers and future research 73 10. Bibliography 75 Acknowledgements The authors are grateful to Leonie Fleischmann and Vladimir Kmec for their assistance in the preparation of this report and to Philip Lewis, Desislava Stoitchkova and Natasha Bevan in the British Academy’s international policy team. -

What Is Palestine/Israel? Answers to Common Questions Sonia K

® What is Palestine/Israel? Answers to common questions Sonia K. Weaver Partially destroyed olive grove and wall construction on northern edge of Bethlehem. ® Acknowledgments Copyright © 2004 Mennonite Central Committee Mennonite Central Committee Canada I would like to thank Deborah Fast, Alain Epp 134 Plaza Drive, Winnipeg, MB R3T 5K9 Weaver, Jan and Rick Janzen, J. Daryl Byler, William Janzen, Mark Beach, Patricia Shelly, Mennonite Central Committee 21 South 12th Street, PO Box 500, Calvin and Marie Shenk, John F. Lapp and Ron Akron, PA 17501-0500 Flaming for having read through previous versions of this booklet. Their perceptive comments have All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any greatly strengthened this piece. means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Design by Roberta Fast Photos by Matthew Lester and Ryan Beiler Printed in Canada. National Library of Canada ISBN: 0-9735784-1-6 Table of Contents 1. Introduction. 2 2. Geography What is Israel? . 4 What is Palestine?. 5 Why do some people refer to Palestine/Israel or Israel/Palestine? . 5 What are the Occupied Territories? . 6 What is the West Bank? . 6 What is the Gaza Strip?. 7 How are Israeli settlements altering the geography of Palestine/Israel?. 7 3. History Who are the Palestinians? . 10 What is Zionism?. 11 How was the State of Israel established? What was the Partition Plan?. 12 What is the relationship between the Holocaust and the State of Israel?. -

Invest in Peace the Church of Scotland World Mission Council © Bertholt Werner 01/02

invest in peace The Church of Scotland World Mission Council © Bertholt Werner 01/02 Foreword We invest so much in war: it is time to there; and we are part of Christian Aid which has been doing invest in peace. wonderful things in that part of the world for years. The second reason is that we have strong and sensitive partnerships with the Peace in Israel and Palestine is very important for the peace of local Christians in Israel and Palestine and their voices inform the world: much tension and hostility between the Arab world everything in this booklet. What a tragedy it is that Christians and the West has its roots in the history of Israel and Palestine. from abroad can come and go to and from “the Holy Land” and Anything that can be done to help peace-making in that tiny, never meet the Christians who live and suffer there. The third blood-stained wonderful part of the world is precious. Anything reason that this booklet should be read and listened to is that it that can be done to build peace-making in that part of the world tries to understand the situation in Israel and Palestine from the where Jesus said “Blessed are the peace-makers” is precious. point of view of the poorest and the most oppressed. Here is an opportunity for every individual to invest in peace. There is an old rabbinic saying Ten measures of beauty gave God to In this booklet there are invitations to give five pounds of your the world: nine to Jerusalem and one to the remainder. -

Talking to the Other: Jewish Interfaith Dialogue with Christians and Muslims

Talking to the Other Jacob said to Esau: I have seen your face as if seeing the face of God and you have received me favourably. (Genesis 33:10) Talking to the Other Jewish Interfaith Dialogue with Christians and Muslims Jonathan Magonet The publication of this book was made possible through a subsidy from the Stone Ashdown Trust Published in 2003 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com In the United States and Canada distributed by Palgrave Macmillan a division of St. Martin’s Press 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © Jonathan Magonet, 2003 The right of Jonathan Magonet to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN 1 86064 905 X A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library Typeset in Caslon by Dexter Haven Associates, London Printed and bound in Great Britain by MPG Books, Bodmin Contents Foreword, by Prince Hassan bin Tallal vii Preface xiii 1 Interfaith Dialogue – A Personal Introduction 1 From Theory to Practice 2 The Challenge to Judaism of Interfaith Dialogue 11 3 Chances and Limits of Multicultural Society 23 4 Reflections