Boston Harbor Islands General Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Harbor Watersheds Water Quality & Hydrologic Investigations

Boston Harbor Watersheds Water Quality & Hydrologic Investigations Fore River Watershed Mystic River Watershed Neponset River Watershed Weir River Watershed Project Number 2002-02/MWI June 30, 2003 Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection Bureau of Resource Protection Boston Harbor Watersheds Water Quality & Hydrologic Investigations Project Number 2002-01/MWI June 30, 2003 Report Prepared by: Ian Cooke, Neponset River Watershed Association Libby Larson, Mystic River Watershed Association Carl Pawlowski, Fore River Watershed Association Wendy Roemer, Neponset River Watershed Association Samantha Woods, Weir River Watershed Association Report Prepared for: Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection Bureau of Resource Protection Massachusetts Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Ellen Roy Herzfelder, Secretary Department of Environmental Protection Robert W. Golledge, Jr., Commissioner Bureau of Resource Protection Cynthia Giles, Assistant Commissioner Division of Municipal Services Steven J. McCurdy, Director Division of Watershed Management Glenn Haas, Director Boston Harbor Watersheds Water Quality & Hydrologic Investigations Project Number 2002-01/MWI July 2001 through June 2003 Report Prepared by: Ian Cooke, Neponset River Watershed Association Libby Larson, Mystic River Watershed Association Carl Pawlowski, Fore River Watershed Association Wendy Roemer, Neponset River Watershed Association Samantha Woods, Weir River Watershed -

The Changing Flora of the Boston Harbor Islands

The Changing Flora of the Boston Harbor Islands Dale F. Levering, Jr. After more than three and one-half centuries of vicissitude, the deciduous forest that once covered the Boston Harbor islands may have begun to return Situated just to the north of the sandy, up- ing animals, the Eastern Deciduous Forest- lifted coastal plain of Cape Cod and just to the which was dominated by broad-leaved, south of the rocky coastline of northern New round-topped deciduous trees (as opposed to England, the Boston Harbor islands consti- needle-leaved, spire-topped evergreens)-was tute a unique maritime ecosystem. To the a richer source of food for the colonists than south of the Harbor, pines dominate the the evergreen forests to the north and south. sandy, mineral-deficient soil where the land No doubt this was one reason the English meets the sea; to the north, hemlock, white settled northward, rather than southward, pine, spruce, and fir. Some twenty thousand from Plymouth. years ago, when the Pleistocene ice sheet was The present-day vegetation of Moswe- at its maximum, the shoreline lay approxi- tusset Hummock, a small island situated at mately thirty miles east of where it does now; the northern end of Wollaston Beach in when the glacier first began to recede, what Quincy, is perhaps the closest indication we are now the Boston Harbor islands were ex- will ever have of what the Boston Harbor posed as high spots on what was then the islands’ vegetation looked like at the time of mainland. Alluvium from the Boston Basin English settlement. -

Fisheries and Oceans Activities in the North 1979-80

• Goverr.ment of Canada Gouvernernent du Canada I ' Fisheries and Oceans Peches et Oceans FISHERIES AND OCEANS ACTIVITIES IN THE NORTH 1979-80 SH 223 C2813 19 ~o D Fisheries and Oceans Activities In the North 1979-80 INTRODUCTION The growing economic importance of Canada's northern regions, particularly as a source for oil and gas and mineral exploitation, has meant a dramatic increase in the responsibilities and activities of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans in these areas. Not only must the department take action to ensure that fish and marine mammal resources of the North are protected from the various forms of industrial encroachment and are not over-exploited, but it also has a responsibility for producing adequate marine navigation charts for northern waters as well as acquiring the necessary marine science expertise to advise industry and other government departments in many critical areas. The following pages provide a summary of DFO's activities north of 60° during the fiscal year 1979-80, and preview activities for 1980-81. This text will appear as part of the annual publication "Government Activities in the North", produced by the Advisory Committee on Northern Development. GOVERNMENT ACTIVITIES IN THE NORTH - 1979-80 Department of Fisheries and Oceans Responsibilities The department is responsible for fisheries research and management throughout the Canadian North, drawing its authority from several acts, including the significant Fisheries Act. The department implements oceanographic and hydrographic programs and coordinates ocean policies and programs of the federal government. Organization and responsibilities with respect to Fisheries Arctic fisheries management occurs under two regions, the Pacific (Yukon) and the Western (NWT). -

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs 100 Cambridge Street, Suite 900

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs 100 Cambridge Street, Suite 900 Boston, MA 02114 Charles D. Baker GOVERNOR Karyn E. Polito LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR Tel: (617) 626-1000 Matthew A. Beaton Fax: (617) 626-1081 SECRETARY http://www.mass.gov/eea September 21, 2018 CERTIFICATE OF THE SECRETARY OF ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS ON THE NOTICE OF PROJECT CHANGE PROJECT NAME : New Harbor Electric Energy Company (HEEC) Cable Project PROJECT MUNICIPALITY : Boston PROJECT WATERSHED : Boston Harbor EEA NUMBER : 15746 PROJECT PROPONENT : Eversource Energy DATE NOTICED IN MONITOR : August 22, 2018 Pursuant to the Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act (MEPA) (M.G. L. c. 30, ss. 61-62I) and Section 11.06 of the MEPA regulations (301 CMR 11.00), I hereby determine that this project does not require an Environmental Impact Report (EIR). The purpose of the project is to ensure a reliable and uninterrupted power supply to the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority’s (MWRA) Deer Island Treatment Plant (DITP) and to facilitate the commencement of the Boston Harbor Deep Draft Navigation Improvement Project (BHDDNIP) to be undertaken by Army Corps of Engineers (ACOE) and the Massachusetts Port Authority (Massport) (EEA# 12958). The DITP treats wastewater generated by over 2 million residents in 43 communities and its uninterrupted operation is critical for maintaining the ecological health of the Commonwealth’s coastal waters. The BHDDNIP is necessary to maintain the important region-wide benefits of the Port of Boston’s maritime activity. Deepening the navigation channels will accommodate larger cargo vessels with deeper drafts that are increasingly used in the global transfer of goods. -

Ocm06220211.Pdf

THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS--- : Foster F__urcO-lo, Governor METROP--�-��OLITAN DISTRICT COM MISSION; - PARKS DIVISION. HISTORY AND MASTER PLAN GEORGES ISLAND AND FORT WARREN 0 BOSTON HARBOR John E. Maloney, Commissioner Milton Cook Charles W. Greenough Associate Commissioners John Hill Charles J. McCarty Prepared By SHURCLIFF & MERRILL, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL CONSULTANT MINOR H. McLAIN . .. .' MAY 1960 , t :. � ,\ �:· !:'/,/ I , Lf; :: .. 1 1 " ' � : '• 600-3-60-927339 Publication of This Document Approved by Bernard Solomon. State Purchasing Agent Estimated cost per copy: $ 3.S2e « \ '< � <: .' '\' , � : 10 - r- /16/ /If( ��c..c��_c.� t � o� rJ 7;1,,,.._,03 � .i ?:,, r12··"- 4 ,-1. ' I" -po �� ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We wish to acknowledge with thanks the assistance, information and interest extended by Region Five of the National Park Service; the Na tional Archives and Records Service; the Waterfront Committee of the Quincy-South Shore Chamber of Commerce; the Boston Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy; Lieutenant Commander Preston Lincoln, USN, Curator of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion; Mr. Richard Parkhurst, former Chairman of Boston Port Authority; Brigardier General E. F. Periera, World War 11 Battery Commander at Fort Warren; Mr. Edward Rowe Snow, the noted historian; Mr. Hector Campbel I; the ABC Vending Company and the Wilson Line of Massachusetts. We also wish to thank Metropolitan District Commission Police Captain Daniel Connor and Capt. Andrew Sweeney for their assistance in providing transport to and from the Island. Reproductions of photographic materials are by George M. Cushing. COVER The cover shows Fort Warren and George's Island on January 2, 1958. -

Boston Harbor South Watersheds 2004 Assessment Report

Boston Harbor South Watersheds 2004 Assessment Report June 30, 2004 Prepared for: Massachusetts Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Prepared by: Neponset River Watershed Association University of Massachusetts, Urban Harbors Institute Boston Harbor Association Fore River Watershed Association Weir River Watershed Association Contents How rapidly is open space being lost?.......................................................35 Introduction ix What % of the shoreline is publicly accessible?........................................35 References for Boston Inner Harbor Watershed........................................37 Common Assessment for All Watersheds 1 Does bacterial pollution limit fishing or recreation? ...................................1 Neponset River Watershed 41 Does nutrient pollution pose a threat to aquatic life? ..................................1 Does bacterial pollution limit fishing or recreational use? ......................46 Do dissolved oxygen levels support aquatic life?........................................5 Does nutrient pollution pose a threat to aquatic life or other uses?...........48 Are there other water quality problems? ....................................................6 Do dissolved oxygen (DO) levels support aquatic life? ..........................51 Do water supply or wastewater management impact instream flows?........7 Are there other indicators that limit use of the watershed? .....................53 Roughly what percentage of the watersheds is impervious? .....................8 Do water supply, -

The Boston Harbor Project and the Reversal of Eutrophication of Boston Harbor

The Boston Harbor Project and the Reversal of Eutrophication of Boston Harbor Massachusetts Water Resources Authority Environmental Quality Department Report 2013-07 Citation: Taylor DI. 2013. The Boston Harbor Project and the Reversal of Eutrophication of Boston Harbor. Boston: Massachusetts Water Resources Authority. Report 2013-07. 33p. i THE BOSTON HARBOR PROJECT AND THE REVERSAL OF EUTROPHICATION OF BOSTON HARBOR Prepared by David I Taylor MASSACHUSETTS WATER RESOURCES AUTHORITY Environmental Quality Department and Department of Laboratory Services 100 First Avenue Charlestown Navy Yard Boston, MA 02129 (617) 242-6000 June 2013 Report No: 2013-01 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report draws on data collected by a number of monitoring projects. Grateful thanks are extended to the following Principal Investigators (PI) of these projects: Nancy Maciolek and James A. Blake AECOM Environment, Marine & Coastal Center, 89 Water Street, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA Anne E. Giblin and Jane Tucker The Ecosystems Center, Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA Robert J. Diaz Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary, Gloucester Pt., VA 23061, USA Charles T. Costello Division of Watershed Management, Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, 1 Winter Street, Boston MA 02108, USA Kelly Coughlin, Wendy Leo, Ken Keay, Laura Ducott ENQUAD, Massachusetts Water Resources Authority, 100 First Ave, Charlestown Navy Yard, MA 02129 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………. iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY………………………………………………………. 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………. 2 2.0 THE BOSTON HARBOR PROJECT (BHP) AND THE DECREASES IN INPUTS TO BOSTON HARBOR 2.1 Background on the BHP………………………………………… 3 2.2 Changes to the nutrient and organic matter inputs to the harbor…. -

Boston Harbor National Park Service Sites Alternative Transportation Systems Evaluation Report

U.S. Department of Transportation Boston Harbor National Park Service Research and Special Programs Sites Alternative Transportation Administration Systems Evaluation Report Final Report Prepared for: National Park Service Boston, Massachusetts Northeast Region Prepared by: John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center Cambridge, Massachusetts in association with Cambridge Systematics, Inc. Norris and Norris Architects Childs Engineering EG&G June 2001 Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER 5b. GRANT NUMBER 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

Outreach Letter

Massachusetts Port Authority One Harborside Drive, Suite 200S East Boston, MA 02128-2909 Telephone (617) 568-5000 www.massport.com December 2, 2020 Re: Boston Logan International Airport/Critical Airspace Surfaces To the Massachusetts Real Estate Development Community: As the owner and operator of Boston Logan International Airport (Logan Airport), the Massachusetts Port Authority (Massport) is pleased to provide you with a copy of our composite map of Critical Airspace Surfaces for Boston Logan Airport (Airspace Map). The Boston-Logan Airspace Map is designed to inform local, municipal and state planning agencies, regulators and sponsors of real estate projects about Boston-Logan airspace designations and guidelines. Our goal is to enable projects to be planned, permitted and constructed in a manner that avoids any adverse impact on Logan airspace and, consequently, on Logan operations. Massport utilizes the Airspace Map to educate private and public interests on the critical height criteria that must be maintained near the Airport to avoid encroachment into and degradation of Logan’s airspace and provide a reference resource. Encroachment into Logan’s airspace will reduce safety margins and impact runway use patterns over communities. The Airspace Map is available at the following link: https://www.massport.com/logan-airport/about-logan/logan-airspace-map/. Review of the Airspace Map and early coordination with Massport are the essential first steps developers must take before filing with the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) through the 7460 Obstruction Evaluation process. This formal review of specific projects is administered by the FAA for analysis of and determination of “hazard” or “no hazard” to navigable airspace. -

International Black-Legged Kittiwake Conservation Strategy and Action Plan Acknowledgements Table of Contents

ARCTIC COUNCIL Circumpolar Seabird Expert Group July 2020 International Black-legged Kittiwake Conservation Strategy and Action Plan Acknowledgements Table of Contents Executive Summary ..............................................................................................................................................4 CAFF Designated Agencies: Chapter 1: Introduction .......................................................................................................................................5 • Norwegian Environment Agency, Trondheim, Norway Chapter 2: Ecology of the kittiwake ....................................................................................................................6 • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada Species information ...............................................................................................................................................................................................6 • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) Habitat requirements ............................................................................................................................................................................................6 • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland Life cycle and reproduction ................................................................................................................................................................................7 • Icelandic Institute of Natural -

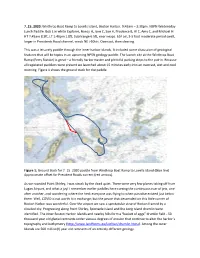

Winthrop Boat Ramp to Lovells Island, Boston Harbor. 9:45Am – 2:30Pm

7_15_2020: Winthrop Boat Ramp to Lovells Island, Boston Harbor. 9:45am – 2:30pm. NSPN Wednesday Lunch Paddle. Bob L in white Explorer, Nancy H, Jane C, Sue H, Prudence B, Al C, Amy C, and Michael H. HT 7:45am 8.3ft, LT 1:46pm 1.8ft, tidal range 6.5ft, near neaps. 65F air, 3-5 foot moderate period swell, larger in Presidents Road channel, winds NE >10kts. Overcast, then clearing. This was a leisurely paddle through the inner harbor islands. It included some discussion of geological features that will be topics in an upcoming NPSN geology paddle. The launch site at the Winthrop Boat Ramp (Ferry Station) is great – a friendly harbormaster and plentiful parking steps to the put-in. Because all registered paddlers were present we launched about 15 minutes early into an overcast, wet and cool morning. Figure 1 shows the ground track for the paddle. Figure 1: Ground track for 7_15_2020 paddle from Winthrop Boat Ramp to Lovells Island (blue line) Approximate offset for President Roads current (red arrows). As we rounded Point Shirley, I was struck by the dead quiet. There were very few planes taking off from Logan Airport, and what a joy! I remember earlier paddles here cursing the continuous roar of jets, one after another, and wondering where the heck everyone was flying to when paradise existed just below them. Well, COVID is not worth it in exchange; but the peace that descended on this little corner of Boston Harbor was wonderful. Over the airport we saw a spectacular view of Boston framed by a clouded sky. -

Historically Famous Lighthouses

HISTORICALLY FAMOUS LIGHTHOUSES CG-232 CONTENTS Foreword ALASKA Cape Sarichef Lighthouse, Unimak Island Cape Spencer Lighthouse Scotch Cap Lighthouse, Unimak Island CALIFORNIA Farallon Lighthouse Mile Rocks Lighthouse Pigeon Point Lighthouse St. George Reef Lighthouse Trinidad Head Lighthouse CONNECTICUT New London Harbor Lighthouse DELAWARE Cape Henlopen Lighthouse Fenwick Island Lighthouse FLORIDA American Shoal Lighthouse Cape Florida Lighthouse Cape San Blas Lighthouse GEORGIA Tybee Lighthouse, Tybee Island, Savannah River HAWAII Kilauea Point Lighthouse Makapuu Point Lighthouse. LOUISIANA Timbalier Lighthouse MAINE Boon Island Lighthouse Cape Elizabeth Lighthouse Dice Head Lighthouse Portland Head Lighthouse Saddleback Ledge Lighthouse MASSACHUSETTS Boston Lighthouse, Little Brewster Island Brant Point Lighthouse Buzzards Bay Lighthouse Cape Ann Lighthouse, Thatcher’s Island. Dumpling Rock Lighthouse, New Bedford Harbor Eastern Point Lighthouse Minots Ledge Lighthouse Nantucket (Great Point) Lighthouse Newburyport Harbor Lighthouse, Plum Island. Plymouth (Gurnet) Lighthouse MICHIGAN Little Sable Lighthouse Spectacle Reef Lighthouse Standard Rock Lighthouse, Lake Superior MINNESOTA Split Rock Lighthouse NEW HAMPSHIRE Isle of Shoals Lighthouse Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse NEW JERSEY Navesink Lighthouse Sandy Hook Lighthouse NEW YORK Crown Point Memorial, Lake Champlain Portland Harbor (Barcelona) Lighthouse, Lake Erie Race Rock Lighthouse NORTH CAROLINA Cape Fear Lighthouse "Bald Head Light’ Cape Hatteras Lighthouse Cape Lookout Lighthouse. Ocracoke Lighthouse.. OREGON Tillamook Rock Lighthouse... RHODE ISLAND Beavertail Lighthouse. Prudence Island Lighthouse SOUTH CAROLINA Charleston Lighthouse, Morris Island TEXAS Point Isabel Lighthouse VIRGINIA Cape Charles Lighthouse Cape Henry Lighthouse WASHINGTON Cape Flattery Lighthouse Foreword Under the supervision of the United States Coast Guard, there is only one manned lighthouses in the entire nation. There are hundreds of other lights of varied description that are operated automatically.