Weaving in Thenzawl : a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol III Issue I June2017

Vol III Issue 1 June 2017 ISSN 2395-7352 MIZORAM UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) MIZORAM UNIVERSITY NAAC Accredited Grade ‘A’ (2014) (A CENTRAL UNIVERSITY) TANHRIL, AIZAWL – 796004 MIZORAM, INDIA i . ii Vol III Issue 1 June 2017 ISSN 2395-7352 MIZORAM UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) Chief Editor Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama Editor Prof. J. Doungel iii Patron : Prof. Lianzela, Vice Chancellor, Mizoram University Advisor : Mr. C. Zothankhuma, IDAS, Registrar, Mizoram University Editorial Board Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama, Dept. of English, Chief Editor Prof. Srinibas Pathi, Dept. of Public Administration, Member Prof. NVR Jyoti Kumar, Dept. of Commerce, Member Prof. Lalhmasai Chuaungo, Dept. of Education, Member Prof. Sanjay Kumar, Dept. of Hindi, Member Prof. J. Doungel, Dept. of Political Science, Member Dr. V. Ratnamala, Dept. of Jour & Mass Communication, Member Dr. Hmingthanzuali, Dept. of History & Ethnography, Member Mr. Lalsangzuala, Dept. of Mizo, Member National Advisory Board Prof. Sukadev Nanda, Former Vice Chancellor of FM University, Bhubaneswar Prof. K. Rama Mohana Rao, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam Prof. K. C. Baral, Director, EFLU, Shillong Prof. Arun Hota, West Bengal State University, Barasat, West Bengal Dr. Sunil Behari Mohanty, Editor, Journal of AIAER, Puducherry Prof. Joy. L. Pachuau, JNU, New Delhi Prof. G. Ravindran, University of Madras, Chennai Prof. Ksh. Bimola Devi, Manipur University, Imphal iv CONTENTS From the Desk of the Chief Editor vii Conceptualizing Traditions and Traditional Institutions in Northeast India 1 - T.T. Haokip Electoral Reform: A Lesson from Mizoram People Forum (MPF) 11 - Joseph C. -

Carrying Capacity Analysis in Mizoram Tourism

Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, Vol. 4, No. 1 (January - June 2019), p. 30-37 Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies ISSN: 2456-3757 Vol. 04, No. 01 A Journal of Pachhunga University College Jan.-June, 2019 (A Peer Reviewed Journal) Open Access https://senhrijournal.ac.in DOI: 10.36110/sjms.2019.04.01.004 CARRYING CAPACITY ANALYSIS IN MIZORAM TOURISM Ghanashyam Deka 1,* & Rintluanga Pachuau2 1Department of Geography, Pachhunga University College, Aizawl, Mizoram 2Department of Geography & Resource Management, Mizoram University, Aizawl, Mizoram *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Ghanashyam Deka: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5246-9682 ABSTRACT Tourism Carrying Capacity was defined by the World Tourism Organization as the highest number of visitors that may visit a tourist spot at the same time, without causing damage of the natural, economic, environmental, cultural environment and no decline in the class of visitors' happiness. Carrying capacity is a concept that has been extensively applied in tourism and leisure studies since the 1960s, but its appearance can be date back to the 1930s. It may be viewed as an important thought in the eventual emergence of sustainability discussion, it has become less important in recent years as sustainability and its associated concepts have come to dominate planning on the management of tourism and its impacts. But the study of carrying capacity analysis is still an important tool to know the potentiality and future impact in tourism sector. Thus, up to some extent carrying capacity analysis is important study for tourist destinations and states like Mizoram. Mizoram is a small and young state with few thousands of visitors that visit the state every year. -

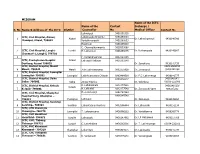

MIZORAM S. No Name & Address of the ICTC District Name Of

MIZORAM Name of the ICTC Name of the Contact Incharge / S. No Name & Address of the ICTC District Counsellor No Medical Officer Contact No Lalhriatpuii 9436192315 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Aizawl, Lalbiakzuala Khiangte 9856450813 1 Aizawl Dr. Lalhmingmawii 9436140396 Dawrpui, Aizawl, 796001 Vanlalhmangaihi 9436380833 Hauhnuni 9436199610 C. Chawngthanmawia 9615593068 2 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Lunglei Lunglei H. Lalnunpuii 9436159875 Dr. Rothangpuia 9436146067 Chanmari-1, Lunglei, 796701 3 F. Vanlalchhanhimi 9612323306 ICTC, Presbyterian Hospital Aizawl Lalrozuali Rokhum 9436383340 Durtlang, Aizawl 796025 Dr. Sanghluna 9436141739 ICTC, District Hospital, Mamit 0389-2565393 4 Mamit- 796441 Mamit John Lalmuanawma 9862355928 Dr. Zosangpuii /9436141094 ICTC, District Hospital, Lawngtlai 5 Lawngtlai- 796891 Lawngtlai Lalchhuanvawra Chinzah 9863464519 Dr. P.C. Lalramenga 9436141777 ICTC, District Hospital, Saiha 9436378247 9436148247/ 6 Saiha- 796901 Saiha Zingia Hlychho Dr. Vabeilysa 03835-222006 ICTC, District Hospital, Kolasib R. Lalhmunliani 9612177649 9436141929/ Kolasib 7 Kolasib- 796081 H. Lalthafeli 9612177548 Dr. Zorinsangi Varte 986387282 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Champhai H. Zonunsangi 9862787484 Hospital Veng, Champhai – 9436145548 8 796321 Champhai Lalhlupuii Dr. Zatluanga 9436145254 ICTC, District Hospital, Serchhip 9 Serchhip– 796181 Serchhip Lalnuntluangi Renthlei 9863398484 Dr. Lalbiakdiki 9436151136 ICTC, CHC Chawngte 10 Chawngte– 796770 Lawngtlai T. Lalengmuana 9436966222 Dr. Vanlallawma 9436360778 ICTC, CHC Hnahthial 11 Hnahthial– 796571 -

Gorkhas of Mizoram: Migration and Settlement

Vol. V, Issue 2 (December 2019) http://www.mzuhssjournal.in/ Gorkhas of Mizoram: Migration and Settlement Zoremsiami Pachuau * Hmingthanzuali † Abstract The Gorkhas were recruited in the British Indian Army after the Anglo-Nepal war. They soon proved to be loyal and faithful to the British. The British took great advantage of their loyalty and they became the main force for the British success in occupation especially in North East India. They came with the British and settled in Mizoram from the late 19 th century. They migrated and settled in different parts of the state. This paper attempts to trace the Gorkha migration since the Lushai Expeditions, how they settled permanently in a place so far from their own country. It also highlights how the British needed them to pacify the Mizo tribe in the initial period of their occupation. Keywords: Gorkhas, Lushai Expeditions, Migration, Mile 45 Dwarband Road Introduction The Mizo had no written language before the coming of the British. From generation to generation, the Mizo history, traditions, customs and practices were handed down in oral forms. The earliest written works about the Mizo were produced almost exclusively by westerners, mainly military and administrative officers who had some connection with Mizoram. This connection was related to the annexation and administration of the area by the British government (Gangte, 2018). The bulk of the early writings on Mizo were done by government officials. Another group of westerners who had done writings on Mizo were the Christian missionaries. It was in the late 1930s that Mizo started writing their own history, reconstructing largely from oral sources. -

Ado)3Fl (Tisl 'S~Aol3 Aqiuewunooa Ieu!6Hjoh

'Ado)3fl (tisl 's~aoL3 AqIuewunooa ieu!6hJOh- Aq!PGS!lAGJt Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized . ........... Z,, .... V V '4% 4±. 4"~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~..... Public Disclosure Authorized V..~~~~~~~~~~...... "C..~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~..... Public Disclosure Authorized [ wflOA ...... 96V3 ;uow;~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~edao ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~jqn~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~ ~...... WUJOZIWjo UQWUSWAO9~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~. .. .. I PREFACE The Mizoram State Roads Project includesaugmentation of the capacityand structural upgradationof selectedroad network in the state. A total of 185.71kmroads will be improved/upgraded,and major maintenanceworks will be carriedout on 518.615kmroads, in 2 Phases.The project was preparedby the ProjectCo-ordinating Consultants (PCC)', on behalf of the PWD, Mizoram.As part of the project preparation,environmental/social assessmentswere carriedout, as requiredby the WorldBank and the Governmentof India. In accordanceto the requirementsof the WorldBank, the environmental/socialassessments (and the outputs) had been subjectedto an IndependentReview. The independentreview 2 evaluatedthe EA processesand outputsin the projectto verify that (a) the EA had been carriedout withoutany biasor influencefrom the projectproponent and/or the PCC,(b) the EA/SAhad beenable to influenceplanning and design of the project;and (c) the outputs, especiallythe mitigation/managementmeasures identified in the EA/SA processesare | adequatefor the -

Serchhip DDMP

TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER Page Chapter I: Introduction 1-10 1.1 Aims and Objectives of the DDMP 1.2 Authority for DDMP: Disaster Management Act 2005 (DM Act 1.3 Evolution of DDMP in brief 1.4 Stakeholders and their responsibilities 1.5 How to use DDMP Framework 1.6 Approval Mechanism of DDMP 1.7 Plan review and updation : Periodicity Chapter 2: Hazard, Vulnerability and Risk Assessment (HVCRA) 11-31 2.1.1 Socio – economic profile of the district 2.1.2 Matrix of Past disasters in the district 2.1.2.2 Report of Natural Calamities (2016 – 2017) 2.1.2.3 Life and cattle loss 2.1.2.4 Damage to infrastructure 2.1.2.5 Economic losses . 2.1.2.6Environmental degradation, livelihood restoration and livestock management 2.1.3.Hazard Risk Vulnerability Assessment (HVCRA) 2.1.3.1 Authority/Agency that carried out HVCRA Chapter 3: Institutional arrangements for Disaster Management 32- 61 3.3.1 DM organizational structure at the national level, 3.3.2 DM organizational structure at the state level including IRS in the State 3.3.3 DM organizational structure at the district level 3.3.3.1 District Disaster Management Authority (DDMA) 3.3.3.2 District Crisis Management Group (CMG) 3.3.3.3 District Disaster Management Committee and Task Forces. 3.3.3.4 IRS in the District. 3.3.3.5 DEOC setup and facilities available in the district 3.3.3.6 Alternate EOC if available and its location 3.3.4 Public-Private Partnership 3.3.4.1 Public and private emergency service facilities available in the district 3.3.5 Forecasting and warning agencies Chapter 4: Prevention and Mitigation Measures 63-72 4.1 Prevention Measures 4.1.1 Specific projects proposed for preventing the disasters. -

Mizoram Public Works Department RP77 Volume 2

Government of Mizoram Public Works Department RP77 Volume 2 ,- :-, - -- f:. Public Disclosure Authorized MizoramState Roads Project -47;~~~~~~7 Public Disclosure Authorized Resestlementand Indigenous Peoples DevelopmentPlan (Phasea4) 34 u Ann.ur.s Public Disclosure Authorized October2001 Public Disclosure Authorized (Original Documentby [CT CES,LBII) TABLE OF CONTENTS ANNEXURE-2.1 SCHEDULE FOR CENSUS SURVEY ANNEXURE-2.2 SCHEDULE FOR SOCIO-ECONOMIC SURVEY ANNEXURE-2.3 WORLD BANK FUNDED SOCIAL & ENVIRONMENT IMPACT ASSESSMENT ANNEXURE-3.1 MIZORAM STATE HIGHWAY RESETTLEMENTAND REHABILITATION POLICY ANNEXURE-3.2 APPROVAL OF MIZORAM STATE HIGHWAY RESETTLEMENT AND REHABILITATION POLICY ANNEXURE-7 DETAILS OF VARIOUS CATEGORIES OF IMPACTED PROPERTIES ALONG PRIORITY ROAD PlA ANNEXURE-8.1 PUBLIC INFORMATION & CONSULTATIONS AIZWAL-LUNGLEI (VIA HMUIFANG) - 100 KM ANNEXURE-8.2 PUBLIC INFORMATION & CONSULTATIONS AND GENERAL EXIBHITS- PHOTOGRAPHS ANNEXURE-8.3 COVERAGE OF PUBLIC CONSULTATIONS IN THE LOCAL MEDIA ANNEXURE-9.1 LAND SETTLEMENT AND THE ACTS OF MIZORAM REGULATIONS AND RULES GOVERNING REVENUE ADMINISTRATION ANNEXURE-9.2 DETAILED STATEMENT OF LANDS OF ORGANISATION/ASSOCIATIONS ETC., REQUIRED FOR IMPROVEMENT & UPGRADATION OF AIZAWL-THENZAWL- LUNGLEI ROAD (VIA HMUIFANG) ANNEXURE-9.3 DETAILED STATEMENT OF LANDS AVAILABLE WITHIN RESPECTIVE VILLAGE COUNCIL JURISDICTIONS & FREE LANDS REQUIRED FOR IMPROVEMENT & UPGRADATION OF AIZAWL-THENZAWL-LUNGLEIROAD ANNEXURE-9.4 DETAILED STATEMENT OF GOVERNMENT DEPARTMENT LANDS REQUIRED FOR IMPROVEMENT & UPGRADATION -

Mizoram: Laboratory Mapping Human Samples Testing Labs, Mizoram

Mizoram: Laboratory Mapping Human Samples Testing Labs, Mizoram Name of the Testing facility: Culture test/ELISA/Rapid Lab/Facility(Lab Postal Address of the Sl. No. Name of Nodal Person Email ID of the Nodal Person Test/Molecular testing, etc categorization: Lab Human) Sakardai CHC, Sakawrdai CHC [email protected] Rapid Test/ 1 Sakawrdai, Dr. H.K. Lalruatfela Laboratory,Aizawl East [email protected] Molecular Test Pin : 796111 Darlawn PHC, Darlawn PHC Rapid Test/ 2 Darlawn, Dr. C. Vanlalremsiama [email protected] Laboratory,Aizawl East Molecular Test Pin : 796111 Khawruhlian PHC, Khawruhlian PHC Rapid Test/ 3 Khawruhlian. Dr. Shahnaz Zothanzami [email protected] Laboratory,Aizawl East Molecular Test Pin : 7960017 Suangpuilawn PHC, Suangpuilawn PHC [email protected] Rapid Test/ 4 Suangpuilawn, Dr. Isaac Lalrawngbawla Laboratory,Aizawl East [email protected] Molecular Test Pin : 796261 Phullen PHC Phullen PHC, Phullen, Rapid Test/ 5 Dr. Vanhmingliani Khiangte [email protected] Laboratory,Aizawl East Pin : 796261 Molecular Test Phuaibuang PHC, Phuaibuang PHC Phuaibuang, 6 Dr. B. Lalramhluna [email protected] Rapid Test Laboratory,Aizawl East Pin : 796261 P.O. : Saitual Thingsulthliah CHC, Thingsulthliah CHC Rapid Test/ 7 Thingsulthliah, Dr. Lalrinkimi Khiangte [email protected] Laboratory,Aizawl East Molecular Test Pin : 796161 Saitual CHC, Saitual CHC Rapid Test/ 8 Saitual, Dr. Lucy Lalsangpuii [email protected] Laboratory,Aizawl East, Molecular Test Pin : 796121 ITI UPHC, ITI ITI UHC Laboratory,Aizawl 9 Aizawl : Mizoram. Dr. Lalnunzira [email protected] Rapid Test East Pin : 796005 Zemabawk UPHC, Zemabawk, Zemabawk UHC Near Zemabawk Rapid Test/ 10 Dr. Lalbiaksangi Royte [email protected] Laboratory,,Aizawl East Thlanmual Molecular Test Aizawl : Mizoram Pin : 796017 Name of the Testing facility: Culture test/ELISA/Rapid Lab/Facility(Lab Postal Address of the Sl. -

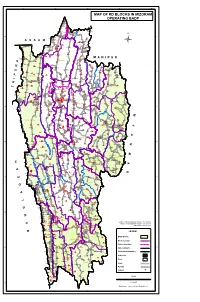

Map of Rd Blocks in Mizoram Operating Badp

92°20'0"E 92°40'0"E 93°60'0"E 93°20'0"E 93°40'0"E MAP OF RD BLOCKS IN MIZORAM Vairengte II OPERATING BADP Vairengte I Saihapui (V) Phainuam Chite Vakultui Saiphai Zokhawthiang North Chhimluang North Chawnpui Saipum Mauchar Phaisen Bilkhawthlir N 24°20'0"N 24°20'0"N Buhchang Bilkhawthlir S Chemphai North Thinglian Bukvannei I Tinghmun BuBkvIaLnKneHi IAI WTHLIR Parsenchhip Saihapui (K) Palsang Zohmun Builum Sakawrdai(Upper) Thinghlun(Lushaicherra) Hmaibiala Veng Rengtekawn Kanhmun South Chhimluang North Hlimen Khawpuar Lower Sakawrdai Luimawi KOLASIB N.Khawdungsei Vaitin Pangbalkawn Hriphaw Luakchhuah Thingsat Vervek E.Damdiai Bungthuam Bairabi New_Vervek Meidum North Thingdawl Thingthelh Lungsum Borai Saikhawthlir Rastali Dilzau H Thuampui(Zawlnuam) Suarhliap R Vengpuh i(Zawlnuam) i Chuhvel Sethawn a k DARLAWN g THINGDAWL Ratu n a Zamuang Kananthar L Bualpui Bukpui Zawlpui Damdiai Sunhluchhip Lungmawi Rengdil N.Khawlek Hortoki Sailutar Sihthiang R North Kawnpui I i R Daido a Vawngawnzo l Vanbawng v i Tlangkhang Kawnpui w u a T T v Mualvum North Chaltlang N.Serzawl i u u Chiahpui i N.E.Tlangnuam Khawkawn s T Darlawn a 24°60'0"N 24°60'0"N Lamherh R Kawrthah Khawlian Mimbung K Sarali North Sabual Sawleng Chilui Zanlawn N.E.Khawdungsei Saitlaw ZAWLNUAM Lungmuat Hrianghmun SuangpuilaPwnHULLEN Vengthar Tumpanglui Teikhang Venghlun Chhanchhuahna kepran Khamrang Tuidam Bazar Veng Nisapui MAMIT Phaizau Phuaibuang Liandophai(Bawngva) E.Phaileng Serkhan Luangpawn Mualkhang Darlak West Serzawl Pehlawn Zawngin Sotapa veng Sentlang T l Ngopa a Lungdai -

20 Year Perspective Plan of Mizoram.Pdf

CONTENTS List of figures 4 List of tables 5 Acknowledgements 6 Prologue 7 Executive Summary 8 Perspective Plan 33 1. Introduction 33 1.1. Background of Tourism Development 1.2. Global Tourism Trends 1.3. Tourism Policy in India 1.4. Objectives of Tourism Development in India 1.5. Environmental and Ecological Parameters 1.6. Tourism Development in the Northeast 1.7. Tourism Development in Mizoram 1.8. Objectives of the Study 1.9. Methodology 2. Mizoram 43 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Geography 2.3 People and Culture 2.4 Natural Environment and Ecology 2.5 Socio-economics 2.6 Evolution 3. Tourism in Mizoram 52 3.1 Tourism Status 3.2 Tourism Potential 3.3 People’s outlook towards Tourism 3.4 Government’s outlook towards Tourism 3.5 Present Budget and Economics of Tourism Development 3.6 Sustainability 1 4. Basic Tourism infrastructure in Mizoram 57 4.1 Communication Network 4.2 Telecommunication Network 4.3 Information Technology 4.4 Entry Permit Offices 4.5 Tourism Department 4.6 Network of Information Centres 4.7 Accommodation Facilities 4.8 Restaurants 4.9 Basic Services 5. Positive and Negative Factors 63 5.1 Northeast Region 5.2 Mizoram State 6. Proposed Tourism Policy 65 6.1 General Recommendations for the Northeast Region 6.2 General Recommendations for Mizoram State 6.3 General Recommendations for the Existing / Proposed Projects 6.4 Specific Unique Projects for Mizoram 6.5 Specific Unique Tourism Circuits for Mizoram 7. Tourism Trends and Implications 98 7.1 Tourism Research and Documentation 7.2 Past & Existing Tourism Trends 7.3 Future Tourism Implications 7.4 Evaluation & Future of Tourism 8. -

Explaining Manipur's Breakdown and Mizoram's Peace

1 Working Paper no.79 EXPLAINING MANIPUR’S BREAKDOWN AND MANIPUR’S PEACE: THE STATE AND IDENTITIES IN NORTH EAST INDIA M. Sajjad Hassan Development Studies Institute, LSE February 2006 Copyright © M.Sajjad Hassan, 2006 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Working Paper, the Development Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Working Paper, of any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Programme, Development Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. 1 Crisis States Programme Explaining Manipur’s Breakdown and Mizoram’s Peace: the State and Identities in North East India M.Sajjad Hassan Development Studies Institute, LSE Abstract Material from North East India provides clues to explain both state breakdown as well as its avoidance. They point to the particular historical trajectory of interaction of state-making leaders and other social forces, and the divergent authority structure that took shape, as underpinning this difference. In Manipur, where social forces retained their authority, the state’s autonomy was compromised. This affected its capacity, including that to resolve group conflicts. Here powerful social forces politicized their narrow identities to capture state power, leading to competitive mobilisation and conflicts. -

Provisional Population Totals, Series-16, Mizoram

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 SERIES-16 MIZORAM PROVIS'IONAL POPULATION \ \ TOTALS Rural-Urban Distribution of Population Paper-2 of 2001 P.K. BHATTACHARJEE of the Indian Administrative Service Director of Census Operations, Mizoram CONTENTS Page No. 1. INTRODUCTORY NOTE v 2. FIGURE AT A GLANCE FOR MIZORAM vi 3. FIGURE AT A GLANCE FOR INDIA VII 4. ANALYTICAL NOTES Population, child population in the age group 0-6 years arid literates by residence and sex - State, District, Cityrrown-2001 Population, child population in the age group 0:6 years and literates by residence and sex - State, District and R. D. Blocks-200t 7 Percentage decadal growth, percentage of child population in the age group 0-6 years by residence and percentage of urban population to total population-200 1 13 Sex ratio of population and sex ratio of children in age group 0-6 years - State, District-2001 15 Literacy rates by residence and sex - State, District-200t 17 Population, percentage decadal growth 1991-2001, sex ratio, literacy by sex - Cities and Towns by size class in the State-200l 20 Towns of 1991 declassified in 2001 23 Appendix III to Table 6 24 Growth of urban population 25 Statement - 1 Percentage of Urban Population to total population and decadal percentage increase - Mizoram and India 1951-2001 26 Statement - 2 Rural Urban distribution of Population - India and States/Union Territories-200 1 27 Provisional Population Totals of Capital - City - Aizawl 31 Statutory and Census Towns, 1991 and 2001 32 Ranking of districts by percentage of urban population, 1991 and 2001 33 Trends in urbanisation, 1991-2001 34 5.