Hey Gringo! What Are You Doing Here?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mormon Colonies in Chihuahua After the 1912 Exodus

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 29 Number 3 Article 2 7-1-1954 The Mormon Colonies in Chihuahua after the 1912 Exodus Elizabeth H. Mills Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Mills, Elizabeth H.. "The Mormon Colonies in Chihuahua after the 1912 Exodus." New Mexico Historical Review 29, 3 (1954). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol29/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Iff W 1'1 Ell CO 72 . I!! .. ·:'"'.1 P..,t....... J, _.J I ( I ' "v', \ I ' I THE MORMON COLONIES NEW MEXICO HISTORICAL REVIEW VoL. xxtx JULY, 1954 No.3 THE MORMON COLONIES IN CHIHUAHUA AFTER THE 1912 EXODUS * By ELIZABETH H. MILLS Introduction N the spring of 1846 the Mormons trekked across the I plains from Nauvoo, Illinois, to the Great Salt Lake Basin, then a part of Mexico, for persecution of the Mor- . mons· in Illinois had led to the decision of their leader, Brigham Young, to seek a land where they .would be free to practice their religion in peace., Here the Mormons pros pered and gradually extended their colonies to the neighbor ing territories. Their original numb_ers were augmented by the immigration of converts from Europe and from Great Britain. By 1887 it was estimated that more than 85,000 immigrants had entered the Great Basin as a result of for eign missionary work, one of the strong features of the Mormon religion.1 The early Mormon colonies in Utah, largely agricultural, were distinguished by the efficient organization of the church and by a spirit of cooperation among the colonists. -

Byu Mpa/Empa Student Handbook

BYU MPA/EMPA STUDENT HANDBOOK MODERN DAY PIONEERS We need modern political, economic, and social pioneers and nonconformists who cannot be deterred by material plenty, political ambition, or social diversions. We need American pioneers with a national and world vision and a national and world identity based on a dedication to the principles of human liberty, social justice, world peace, economic abundance, and the divine rights of man. George Romney 2 Table of Contents MODERN DAY PIONEERS ............................................................................................................................... 2 ACCREDITATION ............................................................................................................................................ 8 NAASPAA-The Global Standard in Public Service Education .................................................................... 8 MISSION STATEMENTS .................................................................................................................................. 9 Brigham Young University Mission Statement ......................................................................................... 9 Marriott School of Business (MSB) Mission Statement .......................................................................... 10 Romney Institute of Public Management (RIPM) Mission Statement .................................................... 10 Learning Outcomes ................................................................................................................................ -

State of Chihuahua, the Mexico North-Western Railway System, Which ~ Fj

~:i-!:i~;;;A;;"-~ SSUMIN G that anyone who devotes sufficient time to this "folder" to read it is either interested in the State of Chihuahua in particular or the Republic of Mexico in general, permit us to introduce the Republic of Mexico's youngest and third largest railway system, which is at present located entirely within the State of Chihuahua, The Mexico North-Western Railway System, which ~ fj. is at present composed of the railroads formerly known as the Rio Grande, Sierra Madre & Pacific, Sierra Madre & Pacific, Chihuahua & Pacific and El Paso Southern, with a mileage of 590 kilometers, which will soon be increased to approximately 800 kilometers (500 miles) by the building of a connecting line between the old Rio Grande, Sierra Madre y Pacifico at Terrazas and the present terminus of the old Sierra Madre & Pacific at Madera, which mileage will be further increased later on by a line westward to the Pacific and various other branches now under consideration, for which federal concessions have been granted. Its present termini are: Chihuahua, where connection is made with National Railways of Mexico, Kansas City, Mexico & Orient and l\!Iineral Railway; El Paso, Tex., where connec tion is made with the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, El Paso & South-Western, Southern. Pacific, Texas & Pacific and National Railways of Mexico; Terrazas and Madera, where connection is made with various stage lines, etc., and Mifiaca, where it connects with the Kansas City, Mexico & Orient Railway. MEXICO NOIITH-WESTEim a RAILWAY COMPANY SCHEDULE OF P4SSENGER TRAINS EL PASO DIVISION CHIHUAHUA DIVISION Eleva- Eleva- No. -

Columbus, New Mexico, and Palomas, Chihuahua: Transnational Landscapes of Violence, 1888-1930 Brandon Morgan

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 9-5-2013 Columbus, New Mexico, and Palomas, Chihuahua: Transnational Landscapes of Violence, 1888-1930 Brandon Morgan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Recommended Citation Morgan, Brandon. "Columbus, New Mexico, and Palomas, Chihuahua: Transnational Landscapes of Violence, 1888-1930." (2013). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/56 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Brandon Morgan Candidate History Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Linda B. Hall, Chairperson Samuel Truett Judy Bieber Maria Lane i COLUMBUS, NEW MEXICO, AND PALOMAS CHIHAUAHUA: TRANSNATIONAL LANDSCAPES OF VIOLENCE, 1888-1930 BY BRANDON MORGAN B.A., History and Spanish, Weber State University, 2005 M.A., History, University of New Mexico, 2007 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July, 2013 ii DEDICATION In memory of Ramón Ramírez Tafoya, chronicler of La Ascensión. For Brent, Nathan, and Paige, who have spent their entire lives thus far with a father constantly working on a dissertation, and especially for Pauline, whose love and support has made the completion of this work possible. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I must admit that there were many moments during which I could not imagine that this project would ever reach completion. -

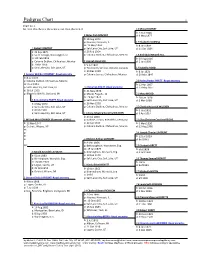

Pedigree Chart 1 Chart No

Pedigree Chart 1 Chart no. 1 No. 1 on this chart is the same as no. 0 on chart no. 0 16 Miles ROMNEY b: 13 Jul 1806 8 Miles Park ROMNEY d: 3 May 1877 b: 18 Aug 1843 p: Nauvoo, Hancock, IL 17 Elizabeth GASKELL m: 10 May 1862 b: 8 Jan 1809 4 Gaskell ROMNEY p: Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, UT d: 11 Oct 1884 b: 22 Sep 1871 d: 26 Feb 1904 p: Saint George, Washington, UT p: Colonia Dublan, Chihuahua, Mexico 18 Archibald Newell HILL m: 20 Feb 1895 b: 20 Aug 1816 p: Colonia Dublan, Chihuahua, Mexico 9 Hannah Hood HILL d: 2 Jan 1900 d: 7 Mar 1955 b: 9 Jul 1842 p: Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, UT p: Tosoronto, Simcoe, Ontario, Canada 19 Isabella HOOD d: 29 Dec 1928 b: 8 Jul 1821 2 George Wilcken ROMNEY -Royal ancestry p: Colonia Juarez, Chihuahua, Mexico d: 20 Mar 1847 b: 8 Jul 1907 p: Colonia Dublan, Chihuahua, Mexico 20 Parley Parker PRATT - Royal ancestry m: 2 Jul 1931 b: 12 Apr 1807 p: Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, UT 10 Helaman PRATT -Royal ancestry d: 13 May 1857 d: 26 Jul 1995 b: 31 May 1846 p: Bloomfield Hills, Oakland, MI p: Mount Pisgah, , IA 21 Mary WOOD m: 20 Apr 1874 b: 18 Jun 1818 5 Anna Amelia PRATT -Royal ancestry p: Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, UT d: 5 Mar 1898 b: 6 May 1876 d: 26 Nov 1909 p: Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, UT p: Colonia Dublan, Chihuahua, Mexico 22 Charles Heinrich WILCKEN d: 4 Feb 1926 b: 5 Oct 1831 p: Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, UT 11 Anna Johanna Dorothy WILCKEN d: 9 Apr 1914 b: 25 Jul 1854 1 Willard Mitt ROMNEY (Governor of MA) p: Dahme, Zarpin, Rheinfeld, Germany 23 Eliza Christina Carolina REICHE b: 12 Mar 1947 d: 22 Jun 1929 b: 1 May 1830 p: Detroit, Wayne, MI p: Colonia Dublan, Chihuahua, Mexico d: 13 Aug 1906 m: p: 24 Joseph Charles LAFOUNT d: b: 12 Jul 1829 p: 12 Robert Arthur LAFOUNT d: bef 1861 b: 9 Mar 1856 sp: p: Belbroughton, Worcester, Eng. -

The Juarez Stake Academy

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1955 The Juarez Stake Academy Dale M. Valentine Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Educational Sociology Commons, History Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Valentine, Dale M., "The Juarez Stake Academy" (1955). Theses and Dissertations. 5183. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/5183 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE JUAREZ STAKE ACADEMY A Thesis Submitted to the Division of Religion Brigham Young University Provo, Utah In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts 199043 by Dale M. Valentine June 1955 iii PREFACE The first inducements to investigate or study the Juarez Stake Academy were received by the author as a result of contact with alumni of that institution. Through associations with and awareness of its alumni it has become apparent to the author that the Juarez Stake Academy has produced graduates of extremely high caliber and character who have been successful in most vocational, academic, and administrative fields. This achievement seems to be far above and out of proportion to the size of the Academy. Such a realization would, quite naturally, invoke an attitude of inquiry to determine what are the underlying causes of such an effect. It is the author!s belief that many of the answers can be found through an objective examination of historical and other factual information dealing with the Juarez Stake Academy. -

Post-Manifesto Polygamy: the 1899-1904 Correspondence of Helen, Owen, and Avery Woodruff

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by DigitalCommons@USU Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2009 Post-Manifesto Polygamy: The 1899-1904 Correspondence of Helen, Owen, and Avery Woodruff Lu Ann Faylor Snyder Phillip A. Snyder Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Snyder, L. A. F., & Snyder, P. A. (2009). Post-manifesto polygamy: The 1899-1904 correspondence of Helen, Owen, and Avery Woodruff. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Post-Manifesto Polygamy The 1899–1904 Correspondence of Helen, Owen, and Avery Woodruff Volume 11 Life Writings of Frontier Women HelenWoodruff C ou rtes y of the Lam bert and Woodruff families Owen Woodruff Avery Woodruff C ou rte sy of t he L C amb ou ert an rt d Woodruff families esy of the Lam bert and W oodruff families Post-Manifesto Polygamy The 1899–1904 Correspondence of Helen, Owen, and Avery Woodruff Edited by Lu Ann Faylor Snyder and Phillip A. Snyder Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 2009 Copyright © 2009 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322–7800 www.usu.edu/usupress Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free paper ISBN: 978–0–87421–739–1 (cloth) ISBN: 978–0–87421–740–7 (e-book) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Post-manifesto polygamy : the 1899-1904 correspondence of Helen, Owen, and Avery Woodruff / edited by Lu Ann Faylor Snyder and Phillip A. -

1. Name of Property Binghampton Rural Historic Landscape Historic Name Binghampton______Other Names/Site Number River Bend Area

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior rt\i National Park Service # NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form I0-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property Binghampton Rural Historic Landscape historic name Binghampton______________ other names/site number River Bend Area 2. Location street & number around intersection of N.Dodge Blvd. & E. River Road not for publication __ city or town north of Tucson _______________________ vicinity __ state Arizona________ code AZ county Pima______ -m code AGO 19 zip code 857 18 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this )C nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

“We Navigated by Pure Understanding” Bishop George T

“We Navigated by Pure Understanding” Bishop George T. Sevey’s Account of the 1912 Exodus from Mexico Michael N. Landon uring July and August 1912, thousands of Mormon colonists fled the turmoil of the Mexican Revolution (fig. 1). As bishop of the Colonia Chuichupa ward, George Sevey led his ward members out of war-torn Mexico and into the United States. The scene was not unfamiliar. During the nineteenth century, Latter-day Saints had fled from Missouri and Illi- nois, and thousands more had experienced the great exodus across the plains to the Salt Lake Valley. Such epic events enrich the heritage of Latter- day Saints, providing cultural meaning and shared identity forged by hard- ship and tragedy. Perhaps the effort to chronicle flight from persecution and intolerance grows naturally from a scriptural tradition that highlights the journeys of strangers and pilgrims looking for safe havens in an inse- cure world. Bishop George Sevey’s understated leadership role in the exo- dus of his ward suggests that he did not imagine himself a larger-than-life Nephi, nor did he suppose his ward’s exodus had great relevance to mankind. But, like Nephi, he thought it worthy of recording for posterity. Bishop Sevey’s memoir of the exodus (pp. 77–101 below) captures a lesser- known chapter of Mormon history and provides a snapshot view of the dynamics of Mormon ward leadership in an extreme situation. As 1912 dawned, Chuichupa’s Latter-day Saints were both prosperous and secure. Railroads, mills, “lush ample range,” and fine flocks and herds gave every indication of “glittering prospects.” Sevey thought rumors of revo- lution and war “too remote to affect us.” He identified “individualistic” atti- ₁ tudes of ward members, and resulting “factions,” as his largest challenge. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 36, No. 4, Fall 2010

Journal of Mormon History Volume 36 Issue 4 Fall 2010 Article 1 2010 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 36, No. 4, Fall 2010 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 36, Fall 2010: Iss. 4. This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 36, No. 4, Fall 2010 Table of Contents ARTICLES --Protecting the Family in the West: James Henry Martineau’s Response to Interfaith Marriage Dixie Dillon Lane, 1 --Hasty Baptisms in Japan: The Early 1980s in the LDS Church Jiro Numano, 18 --“Standing Where Your Heroes Stood”: Using Historical Tourism to Create American and Religious Identities Sarah Bill Schott, 41 --Community of Christ Principles of Church History: A Turning Point and a Good Example? Introduction Lavina Fielding Anderson, 67 --History in the Community of Christ: A Personal View Andrew Bolton, 71 --LDS History Principles: Public Theory, Private Practice Gary James Bergera, 80 --The Sangamo Journal‘s “Rebecca” and the “Democratic Pets”: Abraham Lincoln’s Interaction with Mormonism Mary Jane Woodger and Wendy Vardeman White, 96 --The Forgotten Story of Nauvoo Celestial Marriage George D. Smith, 129 --From Finland to Zion: Immigration to Utah in the Nineteenth Century Kim B. Östman, 166 --“The Lord, God of Israel, Brought Us out of Mexico!” Junius Romney and the 1912 Mormon Exodus Joseph Barnard Romney, 208 REVIEWS --S. -

Historical Narratives

Historical Narratives Volume 14 | 2017-2018 The Undergraduate History Journal of Wesleyan University Historical Narratives Volume 14 | 2017-2018 Editors-in-Chief: Steven Chen Ilana Newman Hai Lun Tan Editorial Staff: Allegra Ayida Christopher Cepil Azher Jaweed Sophie Martin Faculty Advisors: Demetrius Eudell Gary Shaw A Note from the Editors Historical Narratives is the undergraduate history journal of Wesleyan University. In this fourteenth volume of the publication, we continue in the tradition of celebrating student work while providing a platform for academic discourse. The pages that follow feature a wide variety of papers, reflecting the multifarious interests of the student body. This collection of essays consists of environmental, to economic, and social histories while exploring topics of the Amazon, gender, and religious rhetoric. History, as a profession and discipline, allows us to grapple with and make sense of the past. History also sheds light on and preserves the lives, cultures, and stories of the past. The study of history engages us in a mode of historical thinking that allows us to critique moments of historical immorality and constructed narratives. Furthermore, assessing our shared histories can inform our present and guide us into the future. Now, more than ever, historical inquiry urges us to contemplate and evaluate the dimensions of our current socio-economic and political moment. This journal would not have been possible without the enthusiastic contributions from the student body and the support from the History Department. Thank you to the various professors who believe in the possibilities of undergraduate research. Your knowledge and guidance fostered our transformation from students of history to historians-in- training. -

Enter Or Copy the Title of the Article Here

This is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript as accepted for publication. The publisher-formatted version may be available through the publisher’s web site or your institution’s library. Detached from their homeland: the Latter-day Saints of Chihuahua, Mexico Jeffrey S. Smith and Benjamin N. White How to cite this manuscript If you make reference to this version of the manuscript, use the following information: Smith, J. S., & White, B. N. (2004). Detached from their homeland: The Latter-day Saints of Chihuahua, Mexico. Retrieved from http://krex.ksu.edu Published Version Information Citation: Smith, J. S., & White, B. N. (2004). Detached from their homeland: The Latter-day Saints of Chihuahua, Mexico. Journal of Cultural Geography, 21(2), 57-76. Copyright: © Taylor & Francis Group Digital Object Identifier (DOI): doi:10.1080/08873639009478259 Publisher’s Link: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/08873639009478259 This item was retrieved from the K-State Research Exchange (K-REx), the institutional repository of Kansas State University. K-REx is available at http://krex.ksu.edu Detached from Their Homeland: The Latter-day Saints of Chihuahua, Mexico by Jeffrey S. Smith and Benjamin N. White Department of Geography Kansas State University Published by: Journal of Cultural Geography 2004 Vol 21(2): 57-76 For a complete pdf version of this article visit: www.k-state.edu/geography/JSSmith/ Detached from Their Homeland: The Latter-day Saints of Chihuahua, Mexico Abstract. Over the past few decades, the homeland concept has received an ever- increasing amount of attention by cultural geographers. While the debate surrounding the necessity and applicability of the concept continues, it is more than apparent that no other geographic term (including culture areas or culture regions) captures the essence of peoples’ attachment to place better than homeland.