Notes Toward a Vision of the Workers' Movement in Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

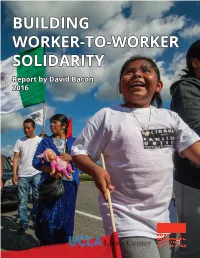

BUILDING WORKER-TO-WORKER SOLIDARITY Report by David Bacon 2016

BUILDING WORKER-TO-WORKER SOLIDARITY Report by David Bacon 2016 1 Table of Contents BUILDING WORKER-TO-WORKER SOLIDARITY Report by David Bacon Introduction..........................................................................................................................................................................1 Defending Miners in Cananea and Residents of the Towns Along the Rio Sonora.....................................................2 Facing Bullets and Prison, Mexican Teachers Stand Up to Education Reforms.........................................................7 Farm Workers Are in Motion from Washington State to Baja California...................................................................11 El Super Workers Fight for Justice in Stores in Both Mexico and the U.S....................................................................16 The CFO Promotes Cross-Border Links to Build Solidarity and Understand Globalization from the Bottom Up..18 Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung—New York Office Address: 275 Madison Avenue, Suite 2114, New York, NY 10016; www.rosalux- nyc.org Institute for Transnational Social Change (ITSC) at the UCLA Labor Center Address: Ueberroth Building, 10945 Le Conte Ave, Los Angeles, CA 90024 New York and Los Angeles, September 2016 INTRODUCTION learn about the truly remarkable campaigns undertaken by workers at the local level facing global companies, but also to highlight the fact that international workers alliances can As part of the UCLA Labor Center’s Global Soli- play a key role in their support. The report describes and darity project, the Institute for Transnational Social Change analyzes the political and economic context in which these (ITSC) provides academic resources and a unique strate- struggles are taking place, and contains as well the analysis gic space for discussion to transnational leaders and their of the Comité Fronterizo de Obreras of the importance of organizations involved in cross-border labor, worker and cross border solidarity and its relation to labor rights under immigrant rights action. -

Mexico – the Year in Review

Mexico – The Year in Review President Enrique Peña Nieto, who had been so successful in advancing his fundamentally conservative economic program during his first year and a half in office, suddenly faced a serious challenge beginning in September 2014 when police apparently cooperating gangsters killed six students, injured at least 25 injured, and kidnapped 43 in the town of Iguala in the state of Guerrero. Protest demonstrations demanding that the students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers College be returned alive, led by parents, students, and teachers quickly spread from Guerrero to Mexico City and around the nation. An international solidarity movement has also developed, with demonstrations at consulates in several countries. At about the same time, it was revealed that the president and his wife Angélica Rivera occupied a home that was owned by a major government contractor, while Secretary of Finance Luis Videgaray had similarly bought a home from a contractor. These revelations of conflict of interest at the highest levels of government, not so different from those portrayed in Luis Estrada’s new political satire film The Perfect Dictatorship, shocked even the jaded Mexican public. The exposé of wrong- doing at the top combined with large social movements from blow created a national political crisis that continued until the Christmas season led to a pause in the protests. The entire situation—the killings, the role of the police, and the corruption at the highest levels of government—has also created an international preoccupation with the Mexican situation. Economic Problems The economic and social crisis has been exacerbated by the country’s economic problems. -

Mexican Labor Year in Review: 2011

Mexican Labor Year in Review: 2011 https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article2452 Mexico Mexican Labor Year in Review: 2011 - Features - Publication date: Tuesday 24 January 2012 Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine - All rights reserved Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine Page 1/18 Mexican Labor Year in Review: 2011 Felipe Calderón's six-year term as president, which began to come to an end in 2011, represents one of the worst periods in modern Mexican history. The war on the drug cartels has taken 50,000 lives while failing to win a decisive victory against the cartels. The economy continues to experience very low growth while workers suffer unemployment or labor in the informal economy. The government's war on the workers continues unabated, with no resolution of the earlier attacks on electrical workers, miners, and airlines employees. The failure of Calderón and the National Action Party (PAN) to successfully resolve the country's most pressing problems while aggravating other issues has led to a decline of the PAN and the resurgence in recent years of the former ruling party, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), known for its powerful political machine based on patronage and corruption. At the same time, despite the ferocious attacks on the electrical workers and miners, workers continue to fight for their unions, for their jobs and their contracts. Throughout the country activists protest against the drug war and army and police human rights violations. A new social movement, the Movement for Peace, Justice, and Dignity led by the poet Javier Sicilia, has challenged Calderón's drug policy, condemned the state's violence, and demanded justice for the indigenous and freedom for the country's political prisoners. -

Union-Party Links and the Reconfiguration of the Labor Movement: Brazil and Mexico 1990-2007 by Andra Olivia Miljanic a Disserta

Union-Party Links and the Reconfiguration of the Labor Movement: Brazil and Mexico 1990-2007 by Andra Olivia Miljanic A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor David Collier, Co-chair Professor Ruth Berins Collier, Co-chair Professor Laura Stoker Professor J. Nicholas Ziegler Professor Harley Shaiken Fall 2010 © Copyright by Andra Olivia Miljanic 2010 All Rights Reserved Abstract Union-Party Links and the Reconfiguration of the Labor Movement: Brazil and Mexico 1990-2007 by Andra Olivia Miljanic Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor David Collier and Professor Ruth Berins Collier, Co-chairs This study examines the reconfiguration of labor movements in Latin America, focusing on the automotive sector in Brazil and Mexico and comparing the two countries across two crucial decades—the 1990s and the 2000s. The analysis situates this reconfiguration in a crucial historical context. Thus, the transitions to democracy and open-market economies that began in most Latin American countries in the 1980s prompted a restructuring of relations within the labor movements, connected with changing relations among labor, state, and business actors. The automotive industry, a pillar of the Brazilian and Mexican economies, experienced a similar economic transition and pattern of foreign direct investment across the two countries. However, over the last two decades, cooperation among auto worker unions—which historically have been among the most important labor actors in these countries—has evolved in opposite directions. -

Bibliography of Mexican Labor – Review Essays

El Colegio de Mexico and Instituto de Investigaciones de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo Social, 1995. 179 pages. Table. In this book professor Zapata presents an analysis of the impact of the process of economic adjustment (1982-1987) and of industrial restructuring (1988-1993) on Mexican unions, looking in particular at the context of the transition from the model of import substitution industrialization to the opening of the Mexican market to foreign competition. The book's six chapters are: Chapter I, "Sindicalismo en Mexico"; Chapter II "Mercados de trabajo, remuneraciones y empleo en la decada de los ochenta,"; Chapter III, "Politicas laborales y restructuracion economica,"; Chapter IV, "El conflicto laboral: ?arma de lucha o mecanismo de transaccion?; Chapter V "El debate sobre la reforma a la Ley Federal del Trabajo (1989-1992); Chapter VI "Sindicalismo y regimen corporativo." Fernando Zertuche Munoz. Ricardo Flores Magon. El Sueno Alternativo. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Economica, 1995. Photographs. Bibliography. 257 pages. Fernando Zertuche is the author of several studies of Mexican political and intellectual figures. For this book Zertuche Munoz has written a 50-page biography of Ricardo Flores Magon and collected a number of his most important essays, manifestos, and letters. There is also a short bibliography of the major workers on Flores Magon. II – Bibliography of Mexican labor – review essays. Maria Cristina Bayon. El sindicalismo automotriz mexicano frente a un nuevo escenario: una perspective desde los liderazgos. Mexico: Facultad Latinoamricana de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO) and Juan Pablos Editor, 1997. 207 pages. Notes, bibliography. Maria Cristina Bayon's book represents an important contribution both to the study of the automobile industry and to the more general discussion of the nature of Mexican labor unions. -

Mexico: Trading Away Rights

April 2001 Volume 13, No. 2(B) CANADA/MEXICO/UNITED STATES TRADING AWAY RIGHTS The Unfulfilled Promise of NAFTA’s Labor Side Agreement ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.............................................................................................................................. iii TERMS AND ACRONYMS..........................................................................................................................iv NAALC Objectives and Obligations .............................................................................................................. vii NAALC LABOR RIGHTS PRINCIPLES..................................................................................................... viii I. SUMMARY................................................................................................................................................1 Structural Weaknesses ........................................................................................................................2 Timid Use of the NAALC by the Parties ..............................................................................................3 Key Facets of NAO and Labor Ministry Work on Cases........................................................................3 Utilizing the NAALC’s Potential.........................................................................................................4 II. FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS.................................................................................................5 General Findings and Recommendations -

MEXICAN LABOR BIBLIOGRAPHY Introduction

November 20, 2002 MEXICAN LABOR BIBLIOGRAPHY By Dan La Botz [This bibliography is a work in progress.] Table of Contents: Introduction I – Bibliography of Mexican Labor, short entries II – Bibliography of Mexican Labor, review essays (longer reviews) III – Bibliography of Mexican Oil Industry and Unions IV – Bibliography of Mexican Rural Workers and Indigenous People V – Bibliography of Mexican Politics VI – Bibliography of Archives and Historiography Introduction I originally wrote many of these notes, annotations and reviews for Mexican Labor News and Analysis, an electronic newsletter about Mexican workers and labor unions that I have edited for the last several years. (See MLNA at: http://www.ueinternational.org/ Now I have put these notes and reviews together to comprise an annotated bibliography of books in English and Spanish dealing mostly with the modern Mexican labor movement, that is since the mid-nineteenth century. This bibliography includes historical and social science studies of the working class and labor unions, and labor leaders' biographies. There are also related books on social movements and politics. In addition, because the subject matter is often closely related, I have included a number of books dealing with economic history and studies of specific industries. Because of their importance to the labor movement, this bibliography also includes many books on the history of the Mexican anarchist, socialist, and communist movements, and related biographies. Finally, because of the intertwined history of the Mexican Revolution and Mexican labor organizations, I have also included many of the important books dealing with the Mexican Revolution. A bibliography such as this is necessary for several reasons. -

Mexico-US Migration and Labor Unions

The Center for Comparative Immigration Studies CCIS University of California, San Diego Mexico-U.S. Migration and Labor Unions: Obstacles to Building Cross-Border Solidarity By Julie Watts Visiting Fellow, Center for Comparative Immigration Studies Working Paper 79 June 2003 Mexico-U.S. Migration and Labor Unions: Obstacles to Building Cross-Border Solidarity Julie Watts Visiting Fellow, Center for Comparative Immigration Studies ********** Abstract. Despite persistent Mexican migration, deepening North American economic integration, and the recent predominance of migration on the U.S.-Mexico bi-national agenda, cross-border labor union efforts to collaborate on immigration policy and migrant worker rights have been sporadic, reactive, and lacking in concerted action. Based on recent interviews conducted with U.S. and Mexican labor union representatives, migration scholars, immigrant advocacy groups, and government officials, Watts examines the historical, political, and institutional obstacles to cross-border labor union solidarity on migration issues. Over the last decade, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) has deepened economic integration between the U.S. and Mexico by lowering barriers to trade and investment. Since 1993, the value of trade between the U.S. and Mexico has almost tripled from $81 billion to $232 billion and Mexico is now the second largest trading partner for the U.S. after Canada.1 Although not facilitated by NAFTA, 2 Mexico-U.S. migration also has increased and is equally vital to the region. Between 1994 and 2001, annual legal and illegal Mexico-U.S. migration increased from 300,000 to 500,000.3 Over a 10-year period, the Mexican-born population in the U.S. -

MEXICAN LABOR BIBLIOGRAPHY Introduction

November 20, 2002 MEXICAN LABOR BIBLIOGRAPHY By Dan La Botz [This bibliography is a work in progress.] Table of Contents: Introduction I – Bibliography of Mexican Labor, short entries II – Bibliography of Mexican Labor, review essays (longer reviews) III – Bibliography of Mexican Oil Industry and Unions IV – Bibliography of Mexican Rural Workers and Indigenous People V – Bibliography of Mexican Politics VI – Bibliography of Archives and Historiography Introduction I originally wrote many of these notes, annotations and reviews for Mexican Labor News and Analysis, an electronic newsletter about Mexican workers and labor unions that I have edited for the last several years. (See MLNA at: http://www.ueinternational.org/ Now I have put these notes and reviews together to comprise an annotated bibliography of books in English and Spanish dealing mostly with the modern Mexican labor movement, that is since the mid-nineteenth century. This bibliography includes historical and social science studies of the working class and labor unions, and labor leaders' biographies. There are also related books on social movements and politics. In addition, because the subject matter is often closely related, I have included a number of books dealing with economic history and studies of specific industries. Because of their importance to the labor movement, this bibliography also includes many books on the history of the Mexican anarchist, socialist, and communist movements, and related biographies. Finally, because of the intertwined history of the Mexican Revolution and Mexican labor organizations, I have also included many of the important books dealing with the Mexican Revolution. A bibliography such as this is necessary for several reasons. -

Articolo Sisp 2016

Mexico's labour movement in transition: the case of the Authentic Labour Front (FAT) by Daniela Barberis Università degli Studi di Torino Prepared for delivery at the annual conference of the Società Italiana di Scienza Politica (SISP) Milan, September 15-17, 2016 Introduction In Latin America labour movements had a central role in shaping regime dynamics at the beginning of the twentieth century. In this period labour legislation in Latin America was aimed at protecting individual workers from employer abuse and arbitrariness. The intent of the legislation reflected a particular political and economic period in which expanded industrialization led to a more inclusive approach toward workers and unions. Examples include Peron in Argentina, Vargas in Brazil, and Cardenas in Mexico. Nonetheless, the state's protective attitude toward workers reflected a paternalistic rather than a democratic and rights-based state. As Bronstein (1997) has indicated, collective rights have always been somewhat limited in Latin America. Collective rights legislation has been characterized by a high degree of state intervention in an effort to control the political radicalism and militancy of workers' organizations. In the 1960s and 1970s, workers and union leaders suffered severe and continuous repression of repressive regimes, not only in the Southern Cone (Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, and Chile) but in many Latin American countries. After the repressive dictatorships, the democratic transitions in the 1980s greatly expanded labour's sphere of action. But in no Latin American country can we say that a liberal rights regime—with full union autonomy, free collective bargaining, and the full right to strike—took shape. -

Combating Violence in Juarez, Mexico: Political Opportunities for Women to Resist Gender

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Honors Program Senior Projects WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2004 Combating Violence in Juarez, Mexico: Political Opportunities for Women to Resist Gender. Class, and Labor Oppression Dana (Dana Marie) Kelly Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Kelly, Dana (Dana Marie), "Combating Violence in Juarez, Mexico: Political Opportunities for Women to Resist Gender. Class, and Labor Oppression" (2004). WWU Honors Program Senior Projects. 216. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors/216 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Honors Program Senior Projects by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Combating Violence in Juarez, Mexico: Political Opportunities for Women to Resist Gender. Class, and Labor Oppression Dana Kelly Spring 2004 WESTERN WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY An equal opportunityuniversity Honors Program HONORS THESIS In presenting this Honors paper in partial requirements for a bachelor’s degree at Western Washington University, I agree that the Library shall make its copies freely available for inspection. I further agree that extensive copying of this thesis is allowable only for scholarly purposes. It is understood that any publication of this thesis for commercial -

Street Democracy Sandra C

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and University of Nebraska Press Chapters 2017 Street Democracy Sandra C. Mendiola García Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples Mendiola García, Sandra C., "Street Democracy" (2017). University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters. 381. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples/381 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Nebraska Press at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Street Democracy Buy the Book The Mexican Experience William H. Beezley, series editor Buy the Book VENDORS, VIOLENCE, AND PUBLIC SPACE IN LATE TWENTIETH- CENTURY MEXICO Sandra C. Mendiola García University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln and London Buy the Book © 2017 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Mendiola García, Sandra C., author. Title: Street democracy: vendors, violence, and public space in late twentieth- century Mexico / Sandra C. Mendiola García. Description: Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, [2017] | Series: The Mexican experience | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016042875 isbn 9780803275034 (cloth: alk. paper) isbn 9780803269712 (pbk.: alk. paper) isbn 9781496200013 (epub) isbn 9781496200020 (mobi) isbn 9781496200037 (pdf) Subjects: lcsh: Street vendors— Political activity— Mexico. | Informal sector (Economics)— Political aspects— Mexico. | Government, Resistance to— Mexico. | Vending stands— Political aspects— Mexico.