Kinixys Homeana Bell 1827 – Home's Hinge-Back Tortoise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

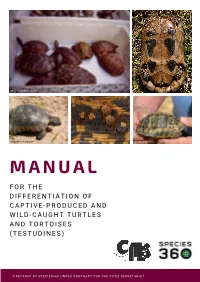

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises Edited by Ian R. Swingland and Michael W. Klemens IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group and The Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) No. 5 IUCN—The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC 3. To cooperate with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the in developing and evaluating a data base on the status of and trade in wild scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biological flora and fauna, and to provide policy guidance to WCMC. diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their con- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna servation, and for the management of other species of conservation concern. and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, sub- vation of species or biological diversity. species, and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintain- 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: ing biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and vulnerable species. • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of biological diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conserva- tion Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitor- 1. -

Aldabrachelys Arnoldi (Bour 1982) – Arnold's Giant Tortoise

Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation ProjectTestudinidae of the IUCN/SSC — AldabrachelysTortoise and Freshwater arnoldi Turtle Specialist Group 028.1 A.G.J. Rhodin, P.C.H. Pritchard, P.P. van Dijk, R.A. Saumure, K.A. Buhlmann, J.B. Iverson, and R.A. Mittermeier, Eds. Chelonian Research Monographs (ISSN 1088-7105) No. 5, doi:10.3854/crm.5.028.arnoldi.v1.2009 © 2009 by Chelonian Research Foundation • Published 18 October 2009 Aldabrachelys arnoldi (Bour 1982) – Arnold’s Giant Tortoise JUSTIN GERLACH 1 1133 Cherry Hinton Road, Cambridge CB1 7BX, United Kingdom [[email protected]] SUMMARY . – Arnold’s giant tortoise, Aldabrachelys arnoldi (= Dipsochelys arnoldi) (Family Testudinidae), from the granitic Seychelles, is a controversial species possibly distinct from the Aldabra giant tortoise, A. gigantea (= D. dussumieri of some authors). The species is a morphologi- cally distinctive morphotype, but has so far not been genetically distinguishable from the Aldabra tortoise, and is considered synonymous with that species by many researchers. Captive reared juveniles suggest that there may be a genetic basis for the morphotype and more detailed genetic work is needed to elucidate these relationships. The species is the only living saddle-backed tortoise in the Seychelles islands. It was apparently extirpated from the wild in the 1800s and believed to be extinct until recently purportedly rediscovered in captivity. The current population of this morphotype is 23 adults, including 18 captive adult males on Mahé Island, 5 adults recently in- troduced to Silhouette Island, and one free-ranging female on Cousine Island. Successful captive breeding has produced 138 juveniles to date. -

Pyxis Arachnoides (Malagasy Spider Tortoise)

Studbook Breeding Programme Pyxis arachnoides (Malagasy spider tortoise) Photo by Frank van Loon Annual Report 2011 / 2012 Frank van Loon studbook keeper KvK nr. 41136106 www.studbooks.eu Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Current living studbook population 4 3. Locations 15 4. Births 15 5. Deaths 15 6. Imports 16 7. Transfers 16 8. Lost to follow up 16 9. Situation in the wild 17 10.Plans for 2013 17 11.Identification of subspecies 18 12.Identification of gender 19 13.Appendix (Husbandry conditions and additional information) 22 1.Introduction This report is an update of the annual report of the Studbook Breeding Programme Pyxis arachnoides published in 2010.The programme aims to form a genetically healthy, reproducing captive population, to study and to gather and distribute as much information about Pyxis arachnoides as possible. In order to keep the studbook manageable (in terms of number of tortoises and contacts between participants and coordinator), it has been decided that the studbook will operate exclusively in Europe. Although Pyxis a. arachnoides appears to be present in Europe in sufficiently large numbers for a viable studbook, the situation for the other two subspecies, brygooi and oblonga, is somewhat different. Although both subspecies are bred in captivity, the total number of living tortoises in the studbook is too low to form a genetical healthy captive population. In the (near) future it might be advisable to establish closer contacts outside Europe to import tortoises of both subspecies (brygooi and oblonga). 2. Current living studbook population Table I: Current living studbook population Pyxis arachnoides per location as registered in the studbook. -

Can Unwanted Suburban Tortoises Rescue Native Hawaiian Plants?

CAN UNWANTED SUBURBAN TORTOISES RESCUE NATIVE HAWAIIAN PLANTS? by David A. Burney, James O. Juvik, Lida Pigott Burney, and Tomas Diagne 104 THE TORTOISE ・ 2012 hrough a series of coincidences, surplus pet tortoises in Hawaii may end up offering a partial solution to the seemingly insurmountable challenge posed by invasive plants in the Makauwahi Cave Reserve Ton Kaua`i. This has come about through a serendipitous intersection of events in Africa, the Mascarene Islands, North America, and Hawaii. The remote Hawaiian Islands were beyond the reach of naturally dispersing island tortoises, but the niches were apparently still there. Giant flightless ducks and geese evolved on these islands with tortoise-like beaks and other adaptations as terrestrial “meso-herbivores.” Dating of these remarkable fossil remains shows that they went extinct soon after the arrival of Polynesians at the beginning of the last millennium leaving the niches for large native herbivores entirely empty. Other native birds, including important plant pollinators, and some plant species have also suffered extinction in recent centuries. This trend accelerated after European settlement ecosystem services and a complex mix of often with the introduction of many invasive alien plants conflicting stakeholder interests clearly requires and the establishment of feral ungulate populations new paradigms and new tools. such as sheep, goats, cattle, and European swine, as Lacking any native mammalian herbivores, the well as other insidious invasives such as deer, rats, majority of the over 1,000 native Hawaiian plant mongoose, feral house cats, and even mosquitoes, species on the islands have been widely regarded which transmit avian malaria to a poorly resistant in the literature as singularly lacking in defensive native avifauna. -

Origins of Endemic Island Tortoises in the Western Indian Ocean: a Critique of the Human-Translocation Hypothesis

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2017 Origins of endemic island tortoises in the western Indian Ocean: a critique of the human-translocation hypothesis Hansen, Dennis M ; Austin, Jeremy J ; Baxter, Rich H ; de Boer, Erik J ; Falcón, Wilfredo ; Norder, Sietze J ; Rijsdijk, Kenneth F ; Thébaud, Christophe ; Bunbury, Nancy J ; Warren, Ben H Abstract: How do organisms arrive on isolated islands, and how do insular evolutionary radiations arise? In a recent paper, Wilmé et al. (2016a) argue that early Austronesians that colonized Madagascar from Southeast Asia translocated giant tortoises to islands in the western Indian Ocean. In the Mascarene Islands, moreover, the human-translocated tortoises then evolved and radiated in an endemic genus (Cylindraspis). Their proposal ignores the broad, established understanding of the processes leading to the formation of native island biotas, including endemic radiations. We find Wilmé et al.’s suggestion poorly conceived, using a flawed methodology and missing two critical pieces of information: the timing and the specifics of proposed translocations. In response, we here summarize the arguments thatcould be used to defend the natural origin not only of Indian Ocean giant tortoises but also of scores of insular endemic radiations world-wide. Reinforcing a generalist’s objection, the phylogenetic and ecological data on giant tortoises, and current knowledge of environmental and palaeogeographical history of the Indian Ocean, make Wilmé et al.’s argument even more unlikely. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12893 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-131419 Journal Article Accepted Version Originally published at: Hansen, Dennis M; Austin, Jeremy J; Baxter, Rich H; de Boer, Erik J; Falcón, Wilfredo; Norder, Sietze J; Rijsdijk, Kenneth F; Thébaud, Christophe; Bunbury, Nancy J; Warren, Ben H (2017). -

(Geochelone Pardalis) on Farmland in the Nama-Karoo

THE STATUS AND ECOLOGY OF THE LEOPARD TORTOISE (GEOCHELONE PARDALIS) ON FARMLAND IN THE NAMA-KAROO MEGAN KAY McMASTER Submitted in fulfilment ofthe academic requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE School ofBotany and Zoology University ofNatal Pieterrnaritzburg March 2001 Preface The experimental work described in this dissertation was carried out in the School of Botany and Zoology, University ofNatal, Pietermaritzburg, from November 1997 to March 2001, under the supervision ofDr. Colleen T. Downs. This study is the original work ofthe author and has not been submitted in any form for any diploma or degree to another university. Where use has been made ofthe work of others, it is duly acknowledged in the text. Each chapter is written in the format ofthe journal it has been submitted to. ..fj~K'. Megan Kay McMaster Pietermaritzburg March 2001 11 This thesis is dedicated to myfather, the late Eric Ralph McMaster, for his constant encouragement and beliefin me, and to my brother, the late Gregory CIifton McMaster,for always making me smile. III Abstract The Family Testudinidae (Suborder Cryptodira) is represented by 40 species worldwide and reaches its greatest diversity in southern Africa, where 14 species occur (33%), ten of which are endemic to the subcontinent. Despite the strong representation ofterrestrial tortoise species in southern Africa, and the importance ofthe Karoo as a centre of endemism ofthese tortoise species, there is a paucity ofecological information for most tortoise species in South Africa. With chelonians being protected in < 15% ofall southern African reserves it is necessary to find out more about the ecological requirements, status, population dynamics and threats faced by South African tortoise species to enable the formulation ofeffective conservation measures. -

Keeping and Breeding Leopard Tortoises (Geochelone Pardalis)

Keeping and breeding Leopard Tortoises Keeping and breeding Leopard Tortoises (Geochelone pardalis). Part 1. Egg-laying, incubation, and care of hatchlings ROBERT BUSTARD HIS captive-breeding/husbandry article on a length of about 15cm (6"). At this time they will Tvery beautiful — indeed magnificent-looking court females assiduously. Females are — tortoise, resulted from a discussion at Council considerably larger, however, before they in October 2001 on the inadequate number of commence breeding with the result that these practical articles on keeping the various species of newly sexually mature males have trouble in reptiles and amphibians being submitted to The mounting them successfully. Although female Herpetological Bulletin. I at once had a `whip leopards take on average a couple of years longer round' getting everyone present to undertake to than males to reach sexual maturity, size/weight is write an article on some topic of their competence. always a much more reliable guide than age in I then asked Council what they wanted me to reptiles and females can be expected to commence write. I think it was Barry Pomfret who actually breeding around a weight of 8kg. `roped me in' for this topic as he said there were a Because of the leopards' highly-domed lot of people keeping 'leopards' these days. Partly carapace males need to be sufficiently large to be I was to blame, as I had said that they were able to successfully mount any given female. `boring', and didn't do much and — insult of Enthusiasm is not enough! As is common in insults — that one would be as good with some tortoises, optimistic males will usually select the garden gnome leopards as with the real thing! largest female on offer. -

Descriptions of Some A.Frican Tortoises

A"nals aftlte Natal Museum. Vol. VI, 1)(1ft 3 DESCRIPTIONS OF SOME AFRICAN TORTOISES. 46 1 Descriptions of some A.frican Tortoises. By John II C\\'itt. With P lates XXXVI-XXXVIII, and 5 Text. fi gul·es. CONTENTS. P elusios s inuatus s inu n.t us Smith J(j2 P elus ios s illu atus zuluensis H elQift 462 P ell1si os ni g r ica. ns n igricnns DonllC/. 4(\3 Pelus ios ni g ri can s castanoides SIIUS)1. n . 4(13 Peil1si os nigr icn.ns ca.stan e us Schw. 464 P elus ios nigricans rh odesianus H ellJi tt 465 Kinixys hellian!} Gray -I n? Kinixys nogll ey i Lataste ·HiS Kin ixys s pekii Gray. 469 Kinixys be lliana. zombensis sllbsp. '11. ·WO Kinixys belJin.nn. zulllon sis subs)1 . n. 47 1 Kinixys n. ustra lis 8p. It. 477 Kinixys da.rlingi Blgr. 4, 1 Kini xys jordn.ni sp . n . 482 Kinixys yonn gi ap. n. 4SG Kini xys lo bn.ts ia na Pou'er 488 H omopus WaMb. ..HHi Pseudomopus g. n . ·Hlli T estlld o L . 4!)H Neotestlldo g. n. 50" 462 JOHN HEWI'IT. THE material dealt wi th in this revi ew has bef' 1l derived from varioll s sources. A good portion of it is contained in the Albany Musemu, and for the loan of specimens I am especia.lly indebted to the Mu seums at Pretoria, Kimberley and Pietermaritzburg. It, may be .aid that the. present study again illustrates the fact t.hat the closer a group of organisms is studied and the wider the area from which they are obt.ained, the greater is the difficnlty ill formulating any clear diagnosis of specific characters. -

Seychelles Giant Tortoise

Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation ProjectTestudinidae of the IUCN/SSC — Aldabrachelys Tortoise and Freshwater hololissa Turtle Specialist Group 061.1 A.G.J. Rhodin, P.C.H. Pritchard, P.P. van Dijk, R.A. Saumure, K.A. Buhlmann, J.B. Iverson, and R.A. Mittermeier, Eds. Chelonian Research Monographs (ISSN 1088-7105) No. 5, doi:10.3854/crm.5.061.hololissa.v1.2011 © 2011 by Chelonian Research Foundation • Published 31 December 2011 Aldabrachelys hololissa (Günther 1877) – Seychelles Giant Tortoise JUSTIN GERLACH 1 1133 Cherry Hinton Road, Cambridge, CB1 7BX United Kingdom [[email protected]] SUMMARY . – The Seychelles Giant Tortoise, Aldabrachelys hololissa (= Dipsochelys hololissa) (Family Testudinidae) is a controversial species possibly distinct from the Aldabra giant tor- toise, A. gigantea (= D. dussumieri of some authors). The species is a morphologically distinctive morphotype, but has so far not been genetically distinguishable from the Aldabra tortoise, and is considered by many researchers to be either synonymous with or only subspecifically distinct from that taxon. It is a domed grazing species, differing from the Aldabra tortoise in its broader shape and reduced ossification of the skeleton; it differs also from the other controversial giant tortoise in the Seychelles, the saddle-backed morphotype A. arnoldi. Aldabrachelys hololissa was apparently extirpated from the wild in the 1800s and is now known only from 37 adults, including 28 captive, 1 free-ranging on Cerf Island, and 8 on Cousine Island, 6 of which were released in 2011 along with 40 captive bred juveniles. Captive reared juveniles show that there is a presumed genetic basis to the morphotype and further genetic work is needed to elucidate this. -

TESTUDINIDAE Geochelone Chilensis

n REPTILIA: TESTUDINES: TESTUDINIDAE Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Ernst, C.H. 1998. Geochelone chilensis. Geochelone chilensis (Gray) Chaco Tortoise Testudo (Gopher) chilensis Gray 1870a: 190. Type locality, "Chili [Chile, South America]. " Restricted to Mendoza. Ar- gentina by Boulenger (1 889) without explanation (see Com- ments). Syntypes, Natural History Museum. London (BMNH), 1947.3.5.8-9, two stuffed juveniles; specimens missing as of August 1998 (fide C.J. McCarthy and C.H. Ernst, see Comments)(not examined by author). Testudo orgentinu Sclater 1870:47 1. See Comments. Testrrdo chilensis: Philippi 1872:68. Testrrrlo (Pamparestrrdo) chilensis: Lindholm 1929:285. Testucin (Chelonoidis) chilensis: Williams 1 950:22. Geochelone chilensis: Williams 1960: 10. First use of combina- tion. Geochelone (Che1onoide.r) chilensis: Auffenberg 197 1 : 1 10. Geochelone donosoharro.si Freiberg 1973533. Type locality, "San Antonio [Oeste], Rio Negro [Province, Argentina]." Ho- lotype, U.S. Natl. Mus. (USNM) 192961, adult male. col- lected by S. Narosky. 22 April 1971 (examined by author). Geochelone petersi Freibeg 197386. Type locality. "Kishka, La Banda. Santiago del Estero [Province, Argentina]." Ho- lotype, USNM 192959. subadult male, collected by J.J. Mar- n cos, 5 May 197 1 (examined by author). Geochelone ootersi: Freiberzm 1973:9 1. E-r errore. Geochelone (Chelonoidis) d1ilensi.s: Auffenberg 1974: 148. MAP. The circle marks the type locality; dots indicate other selected Geochelone ckilensis chilensis: Pritchard 1979:334. records: stars indicate fossil records. Geochelone ckilensis donosoburro.si: Pritchard 1979:335. Chelorroidis chilensis: Bour 1980:546. Geocheloni perersi: Freibeg 1984:30: growth annuli surround the slightly raised vertebral and pleural Chelorioidis donosoharrosi: Cei 1986: 148. -

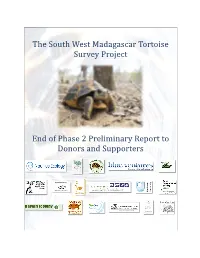

The South West Madagascar Tortoise Survey Project End of Phase 2 Preliminary Report to Donors and Supporters

The South West Madagascar Tortoise Survey Project End of Phase 2 Preliminary Report to Donors and Supporters Southern Madagascar Tortoise Conservation Project Preliminary Donor Report –RCJ Walker 2010 The species documented within this report have suffered considerably at the hands of commercial reptile collectors in recent years. Due to the sensitive nature of some information detailing the precise locations of populations of tortoises contained within this report, the author asks that any public dissemination, of the locations of these rare animals be done with discretion. Cover photo: Pyxis arachnoides arachnoides; all photographs by Ryan Walker and Brain Horne Summary • This summary report documents phase two of the South West Madagascar Tortoise Survey Project (formally the Madagascar Spider Tortoise Conservation and Science Project). The project has redirected focus during this second phase, to concentrate research and survey effort for both of southern Madagascar’s threatened tortoise species; Pyxis arachnoides and Astrocheys radiata. • The aims and objectives of this three phase project, were developed during the 2008 Madagascar Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle IUCN/SSC Red Listing and Conservation Planning Meeting held in Antananarivo, Madagascar. • This project now has five research objectives: o Establish the population density and current range of the remaining populations of P. arachnoides and radiated tortoise A. radiata. o Assess the response of the spider tortoises to anthropogenic habitat disturbance and alteration. o Assess the extent of global internet based trade in Madagascar’s four endemic, Critically Endangered tortoise species. o Assess the poaching pressure placed on radiated tortoises for the local tortoise meat trade. o Carry out genetic analysis on the three subspecies of spider tortoise and confirm that they are indeed three subspecies and at what geographical point one sub species population changes into another.