Plotting Our Raging Hope,ME AGAINST the SYSTEM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here Often? and Light Organ June 12 Various Artists 12” Records Present: a Record Store Day Show Unreleased Songs from the Vault Collection

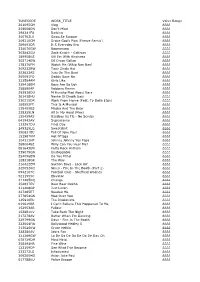

THESE RELEASES WILL BE AVAILABLE JUNE 12TH DROP ARTIST TITLE FORMAT Picture Disc of Original 'Allied Forces' Studio Album Live in Cleveland' 1981 2x LP Single – Tribute 2021 June 12 Triumph 7" Allied Forces” + “Magic Power” Live from 12" Picture Disc Ottawa 1982 (Never Before Released) 11x17 Maple Leaf Gardens Poster (CANADA EXCLUSIVE) June 12 Our Lady Peace Healthy in Paranoid Times LP Detour De Force 30th Anniversary of BNL’s Yellow Tape! Includes two songs from the forthcoming June 12 Barenaked Ladies Cassette Barenaked Ladies album, Detour de Force: “New Disaster” and “Internal Dynamo (radio edit), which is an RSD exclusive Metal Queen (Limited Edition 180 Gram Pink June 12 Lee Aaron LP Vinyl + 20x20 limited edition poster) Comedy Here Often? And Light Organ June 12 Various Artists 12” Records present: A Record Store Day Show Unreleased Songs From The Vault Collection. June 12 Stompin' Tom Connors Vol 4: Let's Smile Again 12” Grey Vinyl with Black Marbling June 12 Greg Keelor Share The Love: Lost Cause Sessions LP "Through The Mists of Time" / "Witch's Spell" June 12 AC/DC 12" Picture Disc Picture Disc June 12 Air People in the City 12" Picture Disc June 12 Al Green Give Me More Love 12" June 12 Albert Collins with the Barrelhouse Live LP June 12 Alestorm Sunset On The Golden Age 2 LP June 12 Alkaline Trio From Here to Infirmary LP June 12 Amy Winehouse Remixes 2LP June 12 Animal Collective Prospect Hummer 12" June 12 Anti-Flag 20/20 Division LP Apollo Brown, Planet Asia, Gensu Dean, June 12 Stitched Up & Shaken 12" Guilty Simpson June 12 Ariana Grande k bye for now (swt live) 3 LP June 12 Ariana Grande k bye for now (swt live) 2 CD June 12 Arthur Verocia Mochilla Presents Timeless: Arthur Verocai 2 LP Gatefold June 12 AVATAR Hunter Gather 2LP Angel Miners & The Lightning Riders Live June 12 AWOLNATION 12” From 2020 June 12 Beastie Boys Aglio E Olio 12" June 12 Beck Hyperspace (2020) LP June 12 Ben Howard Variations Vol. -

The Parkview Pantera

TThehe ParkviewParkview Pantera DECEMBER 2016 NEWS AROUND PHS Volume XLL, Edition I I Toys for Tots gives back to the community that the club accumulates in monetary donations is used to purchase additional toys, which are also sent to the warehouse for distribution. This year on all week- NEWS (2-3) ends through December 17th, JROTC students will be collecting donations in front of several, local Wal- Mart and Kroger stores, according to cadet private Annaliese Mayo, “Some- times, parents can’t afford to buy toys for their kids, and we’re trying to help those FEATURES (5-8) parents out so their kids can have toys too.” Parkview students can also contribute to the cause by donating to the Toys for Tots donation box in the front offi ce. Not everyone can enjoy the festivity of the holidays, Cadet Gunnery Sergeant Samantha Green (left) and Cadet Private Anna Mayo (right) do- and in recognition of such, nate their time to Toys for Tots during the holiday season. (Photo courtesy of Jolie Mayo) JROTC students are working OPINION (9-14) especially hard to ease the By Jenny Nguyen, Copy JROTC helps out in the op- donations through local strain for others who are less Editor erations of the U.S. Marine retail and grocery stores, has fortunate. “[The program] Corps Toys for Tots Pro- successfully expanded their impacts people, and I tell it The Christmas season gram, which serves to collect annual contributions to over to the students all the time. has offi cially come into its and deliver Christmas gifts $70,000. -

Errant Natives, Submissive Obsequious Comprador and The

AFRICA AND THE WORLD CUP: A Beautiful Tragedy By Martin Maitha 2nd July 2010. Soccer City, Johannesburg. The score is 1-1 at the 2010 FIFA World Cup quarter-final between Ghana and Uruguay. In the 120th minute, Ghana have a promising free kick at the edge of the box. Some panicked Uruguayan defending, a proper goalmouth melee. Hang on, what’s this? It’s a penalty. Luis Suarez just saved a certain Ghanaian goal. The only problem is he’s not a goalkeeper, but a forward. He is shown a red card for his troubles. Asamoah Gyan steps up. Could this be the moment an African nation goes to the semi-final, in Africa’s World Cup? Gyan is Ghana’s top scorer at this World Cup, with three goals – two of which were penalties against Serbia and Australia in the group stages. If there was someone you could bet on to have the sangfroid and the cojones to do it, Gyan was that guy. The weight of a continent’s expectation is on his shoulders. He fires a shot, which cannons off the crossbar. Instead of winning it, he condemns Ghana to a needless penalty shootout which they late go on to lose – John Mensah and Dominic Adiyiah miss for Ghana and Sebastian Abreu hits a cheeky Panenka to send Ghana out of the 2010 FIFA World Cup. This memory is so vivid because I watched every heart-rending minute of that match, cursing at Suarez- the ready-made pantomime villain who dashed a continent’s hopes; but more so at Asamoah Gyan? How could he miss? Why was he such a choker? This is the story of Africa and the World Cup as we have always known it. -

Juicy J Blue Dream & Lean 2 Free Download

juicy j blue dream & lean 2 free download Juicy J "Blue Dream & Lean 2" Release Date, Cover Art, Tracklist, Download & Mixtape Stream. The follow-up to Juicy J’s 2011 Blue Dream & Lean is on the way. Juicy took to Instagram yesterday (February 10) to reveal that Blue Dream & Lean 2 will arrive February 16. He also shared the cover art for the mixtape, which appears to be a black-and-white sketch of the The Juiceman. The second installment in the Blue Dream & Lean series will also be hosted by DJ Scream. In 2011, the first version was Juicy’s first offering as a Taylor Gang artist. Last week, Juicy released a freestyle over J. Cole’s “A Tale of Two Cities.” It’s unclear, at the moment, whether the track will appear on BD&L2 . The Three 6 Mafia member is also slated to release his fourth solo studio album, Pure THC: The Hustle Continues, sometime in the new year. The Blue Dream & Lean 2 cover art is as follows: #bluedreamandlean2 2/16 #BDL2 A photo posted by juicyj (@juicyj) on Feb 10, 2015 at 10:02pm PST. (February 11, 2015) UPDATE: Juicy J’s Blue Dream & Lean 2 has been released. Blue Dream & Lean 2 is available for download at DatPiff.com. The Blue Dream & Lean 2 tracklist and stream are as follows: Mixtape Review-Blue Dream & Lean 2 by Juicy J. If you don’t like Juicy J Blue Dream & Lean 2 is not going to change your mind. If you are a fan of the raucous king of repugnant imagery and gleeful mischief this is a must hear. -

Billboard Magazine

Lamar photographed Dec. 30, 2015, in downtown Los Angeles. GRAMMYPREVIEW2016 KENDRICK’S February 13, 2016 SWEET | billboard.com REVENGE No, Lamar doesn’t care about those past snubs. Because the Compton rapper with 11 nominations knows this is his best work ever: ‘I want to win them all’ ‘IT’S STILL TOO WHITE, TOO MALE AND TOO OLD’ Grammy voters speak out! ‘THE SECRET IS… TALENT’ How Chris Stapleton conquered country WE PROUDLY CONGRATULATE OUR GRAMMY® THE RECORDING ACADEMY® SONG OF THE YEAR BEST DANCE/ELECTRONIC ALBUM LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD ED SHEERAN CARIBOU HERBIE HANCOCK “THINKING OUT LOUD” OUR LOVE RECORD OF THE YEAR BEST NEW ARTIST BEST DANCE/ELECTRONIC ALBUM ED SHEERAN COURTNEY BARNETT DISCLOSURE “THINKING OUT LOUD” CARACAL BEST POP SOLO PERFORMANCE RECORD OF THE YEAR ED SHEERAN BEST DANCE/ELECTRONIC ALBUM MARK RONSON* “THINKING OUT LOUD” SKRILLEX & DIPLO “UPTOWN FUNK” SKRILLEX AND DIPLO PRESENT JACK Ü BEST POP SOLO PERFORMANCE ALBUM OF THE YEAR ELLIE GOULDING* BEST DANCE/ELECTRONIC ALBUM ED SHEERAN “LOVE ME LIKE YOU DO” JAMIE XX BEAUTY BEHIND THE MADNESS IN COLOUR BY THE WEEKND BEST POP DUO/GROUP PERFORMANCE (featured artist) MARK RONSON* BEST ROCK PERFORMANCE ALBUM OF THE YEAR “UPTOWN FUNK” ELLE KING “EX’S & OH’S” FLYING LOTUS BEST POP VOCAL ALBUM TO PIMP A BUTTERFLY MARK RONSON* BEST ROCK PERFORMANCE BY KENDRICK LAMAR UPTOWN SPECIAL WOLF ALICE (producer) “MOANING LISA SMILE” BEST DANCE RECORDING ALBUM OF THE YEAR BEST ROCK SONG JACK ANTONOFF ABOVE & BEYOND “WE’RE ALL WE NEED” ELLE KING (OF FUN. AND BLEACHERS) “EX’S & OH’S” -

![Supplemental Information [PDF:203KB]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6202/supplemental-information-pdf-203kb-3186202.webp)

Supplemental Information [PDF:203KB]

Entertainment Business Supplemental Information Three months ended June 30, 2015 July 30, 2015 Sony Corporation Pictures Segment 1 ■ Pictures Segment Aggregated U.S. Dollar Information 1 ■ Motion Pictures 1 - Motion Pictures Box Office for films released in North America - Select films to be released in the U.S. - Top 10 DVD and Blu-rayTM titles released - Select DVD and Blu-rayTM titles to be released ■ Television Productions 3 - Television Series with an original broadcast on a U.S. network - Television Series with a new season to premiere on a U.S. network - Select Television Series in U.S. off-network syndication - Television Series with an original broadcast on a non-U.S. network ■ Media Networks 5 - Television and Digital Channels Music Segment 7 ■ Recorded Music 7 - Top 10 best-selling recorded music releases - Upcoming releases ■ Music Publishing 7 - Number of songs in the music publishing catalog owned and administered as of March 31, 2015 Cautionary Statement Statements made in this supplemental information with respect to Sony’s current plans, estimates, strategies and beliefs and other statements that are not historical facts are forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to, those statements using such words as “may,” “will,” “should,” “plan,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “estimate” and similar words, although some forward- looking statements are expressed differently. Sony cautions investors that a number of important risks and uncertainties could cause actual results to differ materially from those discussed in the forward-looking statements, and therefore investors should not place undue reliance on them. Investors also should not rely on any obligation of Sony to update or revise any forward-looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise. -

Peace Education in Kenya: Tracing Discourse and Action from the National to the Local Level Kathleen Louise Zanoni University of San Francisco, [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Spring 2018 Peace Education in Kenya: Tracing Discourse and Action from the National to the Local Level Kathleen louise Zanoni University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Part of the Education Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Zanoni, Kathleen louise, "Peace Education in Kenya: Tracing Discourse and Action from the National to the Local Level" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 423. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/423 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of San Francisco PEACE EDUCATION IN KENYA: TRACING DISCOURSE AND ACTION FROM THE NATIONAL TO THE LOCAL LEVEL A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the School of Education International and Multicultural Education Department In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education by Kathleen Louise Zanoni San Francisco May 2018 THE UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO PEACE EDUCATION IN KENYA: TRACING DISCOURSE AND ACTION FROM THE NATIONAL TO THE LOCAL LEVEL ABSTRACT Recent Presidential elections in Kenya (2017) resulted in a contested re-run election and demonstrated the presence of systemic corruption, a culture of impunity, and a continued rift among civil society. -

The Hustle Download Torrent Hustle Cat Crack Full PC Game CODEX Torrent Free Download 2021

the hustle download torrent Hustle Cat Crack Full PC Game CODEX Torrent Free Download 2021. Hustle Cat Crack Full PC Game CODEX Torrent Free Download 2021. Hustle Cat Crack is one of the cutest visual new dating games I’ve played so far! The overall atmosphere is very sweet. In Hustle Cat Full Version, you play as 19-year-old high school student Avery Gray, who is currently crashing with their aunt while looking for a job to pay the bills. After searching the internet for jobs and cat videos, Avery comes across a cute cat cafe nearby and they rent! It immediately immerses Avery in a world of coffee, cats, latte art, ridiculously cute co-workers, and their mysterious Hustle Cat Patch, new goth boss. But some of the cats that Avery meets near the cafe are very similar to their new friends. The bubbly yet dedicated chef Mason? Hustle Cat Codex You are Avery Gray, the newest employee of a popular cat cafe called A Cat’s Paw. The coffee is good and the staff is friendly (and quite sweet!) But mysterious. At A Cat’s Paw, you will work hard, but there is still time to get to know your new colleagues! Who is your favorite? The bubbly yet dedicated chef Mason? Or maybe Reese, the fashion-obsessed waiter who knows more than the Hustles Cat reloaded says? And there is always your weird eye boss, the enigmatic Graves. One day you find a strange book in the basement with letters that you cannot read properly. Hustle Cat Free Download. -

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261095CM

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261095CM Vlog ££££ 259008DN Don't Mind ££££ 298241FU Barking ££££ 300703LV Swag Se Swagat ££££ 309210CM Drake God's Plan (Freeze Remix) ££££ 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 234070GW Boomerang ££££ 302842GU Zack Knight - Galtiyan ££££ 189958KS Kill Em With Kindness ££££ 302714EW Dil Diyan Gallan ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 309232BW Tiger Zinda Hai ££££ 253823AS Juju On The Beat ££££ 265091FQ Daddy Says No ££££ 232584AM Girls Like ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 258890AP Robbery Remix ££££ 292938DU M Huncho Mad About Bars ££££ 261438HU Nashe Si Chadh Gayi ££££ 230215DR Work From Home (Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign) ££££ 188552FT This Is A Musical ££££ 135455BS Masha And The Bear ££££ 238329LN All In My Head (Flex) ££££ 155459AS Bassboy Vs Tlc - No Scrubs ££££ 041942AV Supernanny ££££ 133267DU Final Day ££££ 249325LQ Sweatshirt ££££ 290631EU Fall Of Jake Paul ££££ 153987KM Hot N*Gga ££££ 304111HP Johnny Johnny Yes Papa ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 081643EN Party Rock Anthem ££££ 239079GN Unstoppable ££££ 254096EW Do You Mind ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 216422EM Section Boyz - Lock Arf ££££ 325052KQ Nines - Fire In The Booth (Part 2) ££££ 0942107C Football Club - Sheffield Wednes ££££ 5211555C Elevator ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 254637EV Baar Baar Dekho ££££ 311408GP Just Listen ££££ 227485ET Needed Me ££££ 277854GN Mad Over You ££££ 125910EU The Illusionists ££££ 019619BR I Can't Believe This Happened To Me ££££ 152953AR Fallout ££££ 153881KV Take Back The Night ££££ 217278AV Better When -

It's a Bird...It's a Plane...It's a Cayman

DER GASSER MAY/JUNE 2020 IT’S A BIRD...IT’S A PLANE...IT’S A CAYMAN... See Rescue 911 (Pg. 18) 1312 W. Ridge Pike 610-279-4100 Conshohocken, PA 19428 PorscheConshohocken.com THE RTR EXECUTIVE BOARD *Voting Privileges [email protected] President* Jeffrey Walton 484-302-0146 Vice President* Corey McFadden [email protected] Treasurer* Chris Barone [email protected] Secretary* Maggie Nettleton [email protected] Track Chair* Marty Kocse [email protected] Membership Chair* Roy Blumberg [email protected] Der Gasser Editor* Garrett Hughes [email protected] Social Chair* Wendy Walton [email protected] Autocross Chair* Dave Nettleton [email protected] Past President* Graham Knight [email protected] Website Admin Jeffrey Walton [email protected] Awards Chair Kris Haver [email protected] Forum Moderator Brian Minkin [email protected] Rally Master Spencer Wiley [email protected] William G. Cooper Historians [email protected] Debbie Cooper Technical Chair Myles Diamond [email protected] PCA Zone 2 Rep Rose Ann Novotnak [email protected] Myles Diamond Assistant Track Chairs [email protected] Dan Rufer Ian Goddard Chief Instructors [email protected] Jeff Smith Nyssa Capaul Registrars [email protected] Kevin Douglas Pit Marshall Yoyi Fernandez Kris Murphy Safety Chairs [email protected] David Weiss Club Race Christopher Karras [email protected] DER GASSER PAG E 3 DER GASSER May /June 2020 THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF PORSCHE CLUB OF AMERICA, RIESENTÖTER REGION DEPARTMENTS FEATURES 5 Event -

Billboard Magazine

1948 - 2016 Glenn Frey Remembered Rihanna’s Rollout Finally! Inside the rocky launch of Anti Clockwise from top: Hudgens, Jepsen, Hough GREASE LIGHTNING STRIKES February 6, 2016 | billboard.com AGAIN! It’s electrifying! On set as today’s PYTs (Julianne Hough, Vanessa Hudgens, Carly Rae Jepsen), the director of Hamilton and a whole lotta nostalgia try to go together on one wild, loud, live TV event Take It Easy, Glenn You Will Always Be A Part Of Us V z MAT HAYWARD/GETTYMAT IMAGES FOR BILLBOARD Breaking the Hot 100’s top 10 with “Roses,” The Chainsmokers prove they’re not a one-hit wonder. o Title CERTIFICATION Artist Ag The Chainsmokers’ 2 Weeks Last Week This Week PRODUCER (SONGWRITER)S IMPRINT/PROMOTION LABELLABEL Peak Position Weeks On Chart #1 Sorry 2 Justin Bieber 113 1 1 3 WKS 1 BLOOD,SKRILLEX (J.BIEBER,J.MICHAELS, ‘Roses’ Bloom J.TRANTER,M.TUCKER,S.MOORE) SCHOOLBOY/RAYMOND BRAUN/DEF JAM sic, sales data as compiled by Nielsen Music and streaming activity data by online music sources tracked by Nielsen Music. tracked sic, activity data by online music sources sales data as compiled by Nielsen Music and streaming 2 AG Love Yourself Justin Bieber 210 the first time. See Charts Legend on billboard.com/biz for complete rules and explanations. © 2016, Prometheus Global Media, LLC and Nielsen Music, Inc. Global Media, LLC All rights reserved. © 2016, Prometheus for complete rules and explanations. the first time. See Charts on billboard.com/biz Legend 3 3 2 BENNY BLANCO (E.C.SHEERAN,B.LEVIN,J.BIEBER) SCHOOLBOY/RAYMOND BRAUN/DEF JAM HE CHAINSMOKERS opening a Jan. -

55954 Songs, 137.5 Days, 339.51 GB Page 1 of 96 Artist Album

Page 1 of 96 Music 55954 songs, 137.5 days, 339.51 GB Artist Album # Items Total Time A-1 Mash Confusion 18 1:11:30 A-Team Haiku D'Etat - Coup De Theatre 13 55:37 A-Team Haiku D'Etat - Haiku D'Etat 13 1:12:37 A-Team Who Reframed The A-Team? 15 1:07:35 A$AP Rocky Goldie 11 37:47 A$AP Rocky Live.Love.A$AP 16 53:49 A$AP Rocky Long.Live.A$AP 16 1:05:02 A.B.N. A.B.N. (Assholes By Nature) 30 1:32:14 A.B.N. It Is What It Is 18 1:12:37 A.D.O.R. Animal 2000 12 34:18 A.D.O.R. Classic Bangers Volume 1 16 59:53 A.D.O.R. The Concrete 17 55:25 A.D.O.R. Shock Frequency 16 44:28 A.D.O.R. Signature of The Ill 12 41:27 AB-Soul Control System 17 1:11:52 AB-Soul Longterm Mentality 13 55:01 Above The Law Black Mafia Life 15 1:11:24 Above The Law Legends 16 1:04:39 Above The Law Livin' Like Hustlers 10 45:59 Above The Law Time Will Reveal 15 1:06:38 Above The Law Uncle Sam's Curse 12 1:00:19 Above The Law Vocally Pimpin 9 38:50 Abstract Rude Code Name Scorpion 13 51:55 Abstract Rude Making More Tracks 15 1:01:28 Abstract Rude Making Tracks 21 1:12:11 Abstract Rude Rejuvenation 14 52:15 Abstract Rude & Tribe Unique P.A.I.N.T.