Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gaspard Mermillod

JLa LIBERTE ne paraîtra pas de modéré Ribot pour avoir rompu une mission plus féconds dans la vie intérieure et la vie Dans un avenir prochain, la Thurgovie, n»aîn , en raison de la fète de ViSpi toute de conciliation. Voici dans quelles àe conquête de l'Eglise. A plusieurs repri- ce canton paisible et peu passionné, va en- phanie. ¦ «2 circonstances. ses, il a fait appel aux àmes, les conjurant trer probablement dans une vive agitation Aux élections du 22 septembre 1889, les de développer l'esprit de prière en elles, et politique. candidats en présence dans l'arrondisse- chrétien dans leurs Les « démocrates . qui, déjà lors de l'é- DERNIÈRES DÉPÊCHES r0 de renouveler le sens lection de M. Baumann au Conseil ment de Bayonne (l circonscription) étaient pensées et dans leurs actes. Il inspire le des Lncerne, 4 janvier, soir. un catholique qui ne se revendiquait d'au- Etats, avaient, de concert avec les conser- Dans la ville de Lucerne, la revision de cun des anciens partis, et un franc-maçon goût des études, convie le clergé aux tra- vateurs catholiques, vaincu les vieux libé- la Constitution a été rejetée par 1931 vo'ix ennemi notoire des libertés religieuses. Un vaux scientifi ques; en même temps, il cher- raux style Thurgauer-Zeitung, dont le contre 858. certain nombre àe prêtres, qui avaient com- che à ramener les peuples et les sociétés règne exclusif sur le pays date de la révi- Très forte participation des deux côtés. battu ce dernier, furent privés de leur trai- dans l'ordre social chrétien. -

Parish Library Listing

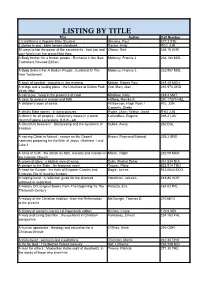

LISTING BY TITLE Title Author Call Number 2 Corinthians (Lifeguide Bible Studies) Stevens, Paul 227.3 STE 3 stories in one : bible heroes storybook Rector, Andy REC JUN 50 ways to tap the power of the sacraments : how you and Ghezzi, Bert 234.16 GHE your family can live grace-filled lives A Body broken for a broken people : Eucharist in the New Moloney, Francis J. 234.163 MOL Testament Revised Edition A Body Broken For A Broken People : Eucharist In The Moloney, Francis J. 232.957 MOL New Testament A book of comfort : thoughts in late evening Mohan, Robert Paul 248.48 MOH A bridge and a resting place : the Ursulines at Dutton Park Ord, Mary Joan 255.974 ORD 1919-1980 A call to joy : living in the presence of God Matthew, Kelly 248.4 MAT A case for peace in reason and faith Hellwig, Monika K. 291.17873 HEL A children's book of saints Williamson, Hugh Ross / WIL JUN Connelly, Sheila A child's Bible stories : in living pictures Ryder, Lilian / Walsh, David RYD JUN A church for all peoples : missionary issues in a world LaVerdiere, Eugene 266.2 LAV church Eugene LaVerdiere, S.S.S - edi A Church to believe in : Discipleship and the dynamics of Dulles, Avery 262 DUL freedom A coming Christ in Advent : essays on the Gospel Brown, Raymond Edward 226.2 BRO narritives preparing for the Birth of Jesus : Matthew 1 and Luke 1 A crisis of truth - the attack on faith, morality and mission in Martin, Ralph 282.09 MAR the Catholic Church A crown of glory : a biblical view of aging Dulin, Rachel Zohar 261.834 DUL A danger to the State : An historical novel Trower, Philip 823.914 TRO A heart for Europe : the lives of Emporer Charles and Bogle, James 943.6044 BOG Empress Zita of Austria-Hungary A helping hand : A reflection guide for the divorced, Horstman, James L. -

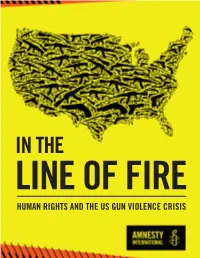

In the Line of Fire 1

1 AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL: IN THE LINE OF FIRE AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL: TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................................8 Key recommendations .................................................................................................................................................18 Acknowledgements .....................................................................................................................................................20 Glossary of abbreviations and a note on terminology .....................................................................................................21 Methodology ...............................................................................................................................................................23 Chapter 1: Firearm Violence: A Human Rights Framework ............................................................................................24 1.1 The right to life .................................................................................................................................... 25 1.2 The right to security of person ................................................................................................................ 25 1.3 The rights to life and to security of person and firearm violence by private actors and in the community ........ 26 1.4 A system of regulation based on international guidelines -

Fr. Joseph Kentenich for the Church

!1 Fr. Joseph Kentenich For the Church Forty-one Texts Exploring the Situation of the Church after Vatican II and Schoenstatt’s Contribution to Help the Church on the way to the New Shore of the Times compiled by Fr. Jonathan Niehaus May 2004 !2 Table of Contents 1. Love of the Church 4 a. Our Attitude 5 b. The Initial Effect of Vatican II 6 c. Our Mission: Anticipate the Church on the New Shore 8 d. Vatican II: Church and World 10 e. The Sickness: Lack of Attachments 12 f. The Remedy: Healthy Attachments 13 g. Attachments as Natural Pre-Experiences 15 2. Deepest Sources / Fullness of Life 16 3. Heroic Virtues 17 a. Faith / Disappearance of Faith 19 b. Faith in Divine Providence as the Remedy 20 4. Taking Christianity Seriously 23 a. A Personal God 24 b. Why did the Marian Movement of the 1950s Fail? 25 c. Not Just in Theory / We Must Shape Life 26 d. Making God present by Making Mary present 27 e. In the Power of the Covenant of Love 29 !3 Compiler’s Note The following texts have been selected from various talks and writings of Fr. Kentenich after the end of his exile in 1965. The selection is meant to shed light on Schoenstatt’s post-conciliar mission (i.e. after Vatican II), especially in light of the legacy of the exile years. The main source is the series Propheta locutus est (Vallendar-Schön- statt, 1981ff, here abbreviated “PLE”), now encompassing 16 volumes. References to Vol. 1 and 2 are from December 1965, Vol. -

The New Organization of the Catholic Church in Romania

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 12 Issue 2 Article 4 3-1992 The New Organization of the Catholic Church in Romania Emmerich András Hungarian Institute for Sociology of Religion, Toronto Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation András, Emmerich (1992) "The New Organization of the Catholic Church in Romania," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 12 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol12/iss2/4 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEW ORGANIZATION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN ROMANIA by Emmerich Andras Dr. Emmerich Andras (Roman Catholic) is a priest and the director of the Hungarian Institute for Sociology of Religion in Vienna. He is a member of the Board of Advisory Editors of OPREE and a frequent previous contributor. I. The Demand of Catholics in Transylvania for Their Own Church Province Since the fall of the Ceausescu regime, the 1948 Prohibition of the Greek Catholic Church in Romania has been lifted. The Roman Catholic Church, which had been until then tolerated outside of the law, has likewise obtained legal status. During the years of suppression, the Church had to struggle to maintain its very existence; now it is once again able to carry out freely its pastoral duties. -

Organizational Structures of the Catholic Church GOVERNING LAWS

Organizational Structures of the Catholic Church GOVERNING LAWS . Canon Law . Episcopal Directives . Diocesan Statutes and Norms •Diocesan statutes actually carry more legal weight than policy directives from . the Episcopal Conference . Parochial Norms and Rules CANON LAW . Applies to the worldwide Catholic church . Promulgated by the Holy See . Most recent major revision: 1983 . Large body of supporting information EPISCOPAL CONFERENCE NORMS . Norms are promulgated by Episcopal Conference and apply only in the Episcopal Conference area (the U.S.) . The Holy See reviews the norms to assure that they are not in conflict with Catholic doctrine and universal legislation . These norms may be a clarification or refinement of Canon law, but may not supercede Canon law . Diocesan Bishops have to follow norms only if they are considered “binding decrees” • Norms become binding when two-thirds of the Episcopal Conference vote for them and the norms are reviewed positively by the Holy See . Each Diocesan Bishop implements the norms in his own diocese; however, there is DIOCESAN STATUTES AND NORMS . Apply within the Diocese only . Promulgated and modified by the Bishop . Typically a further specification of Canon Law . May be different from one diocese to another PAROCHIAL NORMS AND RULES . Apply in the Parish . Issued by the Pastor . Pastoral Parish Council may be consulted, but approval is not required Note: On the parish level there is no ecclesiastical legislative authority (a Pastor cannot make church law) EXAMPLE: CANON LAW 522 . Canon Law 522 states that to promote stability, Pastors are to be appointed for an indefinite period of time unless the Episcopal Council decrees that the Bishop may appoint a pastor for a specified time . -

Roman Catholic Liturgical Renewal Forty-Five Years After Sacrosanctum Concilium: an Assessment KEITH F

Roman Catholic Liturgical Renewal Forty-Five Years after Sacrosanctum Concilium: An Assessment KEITH F. PECKLERS, S.J. Next December 4 will mark the forty-fifth anniversary of the promulgation of the Second Vatican Council’s Constitution on the Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, which the Council bishops approved with an astounding majority: 2,147 in favor and 4 opposed. The Constitution was solemnly approved by Pope Paul VI—the first decree to be promulgated by the Ecumenical Council. Vatican II was well aware of change in the world—probably more so than any of the twenty ecumenical councils that preceded it.1 It had emerged within the complex social context of the Cuban missile crisis, a rise in Communism, and military dictatorships in various corners of the globe. President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated only twelve days prior to the promulgation of Sacrosanctum Concilium.2 Despite those global crises, however, the Council generally viewed the world positively, and with a certain degree of optimism. The credibility of the Church’s message would necessarily depend on its capacity to reach far beyond the confines of the Catholic ghetto into the marketplace, into non-Christian and, indeed, non-religious spheres.3 It is important that the liturgical reforms be examined within such a framework. The extraordinary unanimity in the final vote on the Constitution on the Liturgy was the fruit of the fifty-year liturgical movement that had preceded the Council. The movement was successful because it did not grow in isolation but rather in tandem with church renewal promoted by the biblical, patristic, and ecumenical movements in that same historical period. -

A Long-Simmering Tension Over 'Creeping Infallibility' Published on National Catholic Reporter (

A long-simmering tension over 'creeping infallibility' Published on National Catholic Reporter (http://ncronline.org) A long-simmering tension over 'creeping infallibility' May. 09, 2011 Vatican [1] ordinati.jpg [2] Priests lie prostrate before Pope Benedict XVI during their ordination Mass in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican May 7, 2006. (CNS/Chris Helgren) Rome -- When Pope Benedict XVI used the word "infallible" in reference to the ban on women's ordination in a recent letter informing an Australian bishop he'd been sacked, it marked the latest chapter of a long-simmering debate in Catholicism: Exactly where should the boundaries of infallible teaching be drawn? On one side are critics of "creeping infallibility," meaning a steady expansion of the set of church teachings that lie beyond debate. On the other are those, including Benedict, worried about "theological positivism," meaning that there is such a sharp emphasis on formal declarations of infallibility that all other teachings, no matter how constantly or emphatically they've been defined, seem up for grabs. That tension defines the fault lines in many areas of Catholic life, and it also forms part of the background to the recent Australian drama centering on Bishop William Morris of the Toowoomba diocese. Morris was removed from office May 2, apparently on the basis of a 2006 pastoral letter in which he suggested that, in the face of the priest shortage, the church may have to be open to the ordination of women, among other options. Morris has revealed portions of a letter from Benedict informing him of the action, in which the pope says Pope John Paul II defined the teaching on women priests "irrevocably and infallibly." In comments to the Australian media, Morris said that turn of phrase has him concerned about "creeping infallibility." Speaking on background, a Vatican official said this week that the Vatican never comments on the pope's correspondence but has "no reason to doubt" the authenticity of the letter. -

The Obligation of the Christian Faithful to Maintain

THE OBLIGATION OF THE CHRISTIAN FAITHFUL TO MAINTAIN ECCLESIAL COMMUNION WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO ORDINATIO SACERDOTALIS by Cecilia BRENNAN Master’s Seminar – DCA 6395 Prof. John HUELS Faculty of Canon Law Saint Paul University Ottawa 2016 ©Cecilia Brennan, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………3 1 – THE OBLIGATION TO MAINTAIN ECCLESIAL COMMUNION ………5 1.1 – The Development and Revision of canon 209 §1 …………………………...6 1.1.1 The text of the Canon ………………………………..……………… 7 1.1.2 The Terminology in the Canon …………………………….……..….. 7 1.2 – Canonical Analysis of c. 209 §1 ………………………………………..… 9 1.3 –Communio and Related Canonical Issues ………………………………..... 10 1.3.1 Communio and c. 205 …………..…………………………………… 10 1.3.2 Full Communion and Incorporation into the Church ………….…… 11 1.3.3 The Nature of the Obligation in c. 209 §1 ………………………….. 13 2 –THE AUTHENTIC MAGISTERIUM ………………………………………… 16 2.1 – Magisterium ………………………..………………………………….….… 18 2.1.1 Authentic Magisterium …………….…………………………..……. 18 2.1.2 Source of Teaching Authority….…………….………………………. 19 2.2 – Levels of Authentic Magisterial Teachings ………………………..………. 20 2.2.1. Divinely Revealed Dogmas (cc. 749, 750 §1) …………………..… 22 2.2.2 Teachings Closely Related to Divine Revelation (c. 750 §2) ……..... 25 2.2.3. Other Authentic Teachings (cc. 752-753) ………………………….. 26 2.3 – Ordinary and Universal Magisterium ……………………………………….. 27 2.3.1 Sources of Infallibility ………………………………………………. 29 2.3.2 The Object of Infallibility …………………………..…….….……… 30 3 – ORDINATIO SACERDOTALIS ……………………………………………….. 32 3.1 – Authoritative Status of the Teaching in Ordinatio sacerdotalis ……….…. 33 3.1.1 Reactions of the Bishops ……………………………………………..33 3.1.2 Responsum ad propositum dubium ……………..……………………35 3.2 – Authority of the CDF ………………………………………………………37 3.3 – Exercise of the Ordinary and Universal Magisterium …………………..… 39 3.3.1 An Infallible Teaching ………………….……………..……………. -

The Labor Problem and the Social Catholic Movement in France

THE LABOR PROBLEM AND THE SOCIAL CATHOLIC MOVEMENT IN FRANCE ..s·~· 0 THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW VORIC • BOSTON • CHICAGO • DALlAS ATLANTA • SAN FRANCISCO MACMILLAN &: CO., LtMITIID LONDON • BOMBAY • CALC1/TTA MBLBOURNII THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, LTD. TORONTO THE LABOR PROBLEM AND THE SOCIAL CATHOLIC MOVEMENT IN FRANCE A Study in the History of Social Politics BY PARKER THOMAS MOON Instructor in History in Columbia University Jat\tl !llOtk THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1921 COPYBIGilT, 1921, BY THE MACMILLAN COMPANY. Set up and printed. •Published Ma.y, 1921. !'BIN I'Bb lll' 'l.'lm l1NlTIII> S'l.'AflS OJ Alo!UIOA TO MY MOTHER PREFACE Nor until quite recently: in the United States, has anything like general public attention been directed to one of the most powerful and interesting of contemporary movements toward the solution of the insistent problem of labor unrest. There is a real need for an impartial historical study of this movement and a critical analysis of the forces which lie behind it. Such a need the present narrative does not pretend to satisfy com pletely; but it is hoped that even a preliminary survey, such as this, ·will be of interest to those who concern themselves with the grave social and economic problems now confronting po litical democracy. The movement in question,- generally known as the Social Catholic movement,- has expanded so rapidly in the last few decades that it may now be regarded as a force compar able in magnitude and in power to international Socialism, or to Syndicalism, or to the cooperative movement. On the eve of the Great War, Social Catholicism was represented by or ganizations in every civilized country where there was any considerable Catholic population. -

Liturgical Press Style Guide

STYLE GUIDE LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org STYLE GUIDE Seventh Edition Prepared by the Editorial and Production Staff of Liturgical Press LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Catholic Edition © 1989, 1993, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Cover design by Ann Blattner © 1980, 1983, 1990, 1997, 2001, 2004, 2008 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. Printed in the United States of America. Contents Introduction 5 To the Author 5 Statement of Aims 5 1. Submitting a Manuscript 7 2. Formatting an Accepted Manuscript 8 3. Style 9 Quotations 10 Bibliography and Notes 11 Capitalization 14 Pronouns 22 Titles in English 22 Foreign-language Titles 22 Titles of Persons 24 Titles of Places and Structures 24 Citing Scripture References 25 Citing the Rule of Benedict 26 Citing Vatican Documents 27 Using Catechetical Material 27 Citing Papal, Curial, Conciliar, and Episcopal Documents 27 Citing the Summa Theologiae 28 Numbers 28 Plurals and Possessives 28 Bias-free Language 28 4. Process of Publication 30 Copyediting and Designing 30 Typesetting and Proofreading 30 Marketing and Advertising 33 3 5. Parts of the Work: Author Responsibilities 33 Front Matter 33 In the Text 35 Back Matter 36 Summary of Author Responsibilities 36 6. Notes for Translators 37 Additions to the Text 37 Rearrangement of the Text 37 Restoring Bibliographical References 37 Sample Permission Letter 38 Sample Release Form 39 4 Introduction To the Author Thank you for choosing Liturgical Press as the possible publisher of your manuscript. -

Church Documents Joliet Diocese Life Office – Resource Center

Church Documents Joliet Diocese Life Office – Resource Center Education for Life Catholic documents are made up of two categories: 1) those issued by the Vatican, i.e., popes, ecumenical councils and the Roman Curia; and 2) those issued by the bishops, either as a group, such as the US Conference of Catholic Bishops, or as individuals who are leaders of dioceses. For ease of use, our list of church documents appear in alphabetical order. These documents are for reference purposes, however, we have a limited supply of some of these documents for sale. Sale items are indicated with an asterisk after the title. Title Author Type Date A Culture of Life and the Penalty of Death* US Bishops Conference USCCB/Statement 2005 Ad Tuendam Fidem (To Protect the Faith) John Paul II Apostolic Letter 1998 Address of JPII To a Group of American Bishops US Bishops Conference Address 1983 Atheistic Communism Pius XI Encyclical 1937 Behold Your Mother, Women of Faith US Bishops Conference Pastoral Letter 1973 Blessings of Age US Bishops Conference USCCB/Statement 1999 Catechism of the Catholic Church John Paul II Catechism 1994 Catechism on The Gospel of Life Hardon, Fr. John Catechism 1996 Pontifical Council for Pastoral Charter for Health Care Workers* Assistance Charter 1989 Charter of the Rights of the Family John Paul II Charter 1983 Code of Canon Law Canon Law Society of America Reference 1983 Commentary on Reply of Sacred National Conference of Catholic Congregation on Sterilization Bishops Commentary 1977 Congregation for the Doctrine of the Declaration