Antimicrobial Use and Resistance in Nigeria SITUATION ANALYSIS and RECOMMENDATIONS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

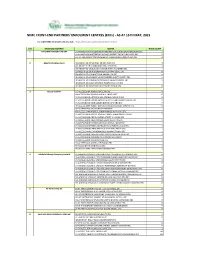

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

Obi Patience Igwara ETHNICITY, NATIONALISM and NATION

Obi Patience Igwara ETHNICITY, NATIONALISM AND NATION-BUILDING IN NIGERIA, 1970-1992 Submitted for examination for the degree of Ph.D. London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 1993 UMI Number: U615538 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615538 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 V - x \ - 1^0 r La 2 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the relationship between ethnicity and nation-building and nationalism in Nigeria. It is argued that ethnicity is not necessarily incompatible with nationalism and nation-building. Ethnicity and nationalism both play a role in nation-state formation. They are each functional to political stability and, therefore, to civil peace and to the ability of individual Nigerians to pursue their non-political goals. Ethnicity is functional to political stability because it provides the basis for political socialization and for popular allegiance to political actors. It provides the framework within which patronage is institutionalized and related to traditional forms of welfare within a state which is itself unable to provide such benefits to its subjects. -

Office of the Auditor-General for the Federation

OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR-GENERAL FOR THE FEDERATION AUDIT HOUSE, PLOT 273 CADASTRAL ZONE AOO, OFF SAMUEL ADEMULEGUN STREET CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT PRIVATE MAIL BAG 128, GARKI ABUJA, NIGERIA LIST OF ACCREDITED FIRMS OF CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS AS AT 2nd MARCH, 2020 SN Name of Firm Firm's Address City 1 Momoh Usman & Co (Chartered Accountants) Lokoja Kogi State Lokoja 2 Sypher Professional Services (Chartered 28A, Ijaoye Street, Off Jibowu-Yaba Accountants) Onayade Street, Behind ABC Transport 3 NEWSOFT PLC SUITE 409, ADAMAWA ABUJA PLAZA,CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT,ABUJA 4 PATRICK OSHIOBUGIE & Co (Chartered Suite 1010, Block B, Abuja Accountants) Anbeez Plaza 5 Tikon Professionals Chartered Accountants No.2, Iya Agan Lane, Lagos Ebute Metta West, Lagos. 6 Messrs Moses A. Ogidigo and Co No 7 Park Road Zaria Zaria 7 J.O. Aiku & Co Abobiri Street, Off Port Harcourt Harbour Road, Port Harcourt, Rivers State 8 Akewe & Co. Chartered Accountants 26 Moleye Street, off Yaba Herbert Macaulay Way , Alagomeji Yaba, P O Box 138 Yaba Lagos 9 Chijindu Adeyemi & Co Suite A26 Shakir Plaza, Garki Michika Street, Area 11 10 DOXTAX PROFESSIONAL SERVICES D65, CABANA OFFICE ABUJA SUITES, SHERATON HOTE, ABUJA. 11 AKN PROJECTS LIMITED D65, CABANA OFFICE ABUJA SUITES, SHERATON HOTEL, WUSE ZONE 4, ABUJA. 12 KPMG Professional Services KPMG Tower, Bishop Victoria Island Aboyade Cole Street 13 Dox'ix Consults Suite D65, Cabana Suites, Abuja Sheraton Hotel, Abuja 14 Bradley Professional Services 268 Herbert Macaulay Yaba Lagos Way Yaba Lagos 15 AHONSI FELIX CONSULT 29,SAKPONBA ROAD, BENIN CITY OREDO LGA, BENIN CITY 1 16 UDE, IWEKA & CO. -

Dutch68-2003.Pdf

1 CENTRAL BANK OF NIGERIA TRADE AND EXCHANGE DEPARTMENT FOREIGN EXCHANGE AUCTION NO. 68/2003 OF 8TH SEPTEMBER, 2003 FOREIGN EXCHANGE AUCTION SALES RESULT APPLICANT NAME FORM BID CUMM. BANK S/N A. SUCCESSFUL BIDS M/A NO R/C NO APPLICANT ADDRESS RATE AMOUNT TOTAL PURPOSE NAME REMARKS 1 ALLI TAIWO AA1227615 B843011 22, MONTGOMERY ROAD, YABA, LAGOS 129.5000 29,480.12 29,480.12 SCHOOL FEES AFRI 0.0503 2 DIMENSIONS CEILING PRODUCTS LTD. MF0521807 99653 109 TAFAWA BALEWA CRESCENT,SURULERE 129.5000 28,997.20 58,477.32 OWACOUSTIC SUSPENSION GRIDS SYSTEM FBN 0.0495 3 HARBINGER INVESTMENTS LIMITED MF0470384 218463 NO.60A, OGUDU-OJOTA ROAD, OGUDU GRA, LAGOS STATE,129.4000 NIGERIA 111,349.75 169,827.07 IMPORT OF GRANITE SLAB & TILES, TOILETRIES TRIUMPH 0.1898 4 KIMATRAI NIGERIA LIMITED MF0485624 38603 88, NNAMDI AZIKIWE STREET, LAGOS 129.2000 99,700.61 269,527.68 INSTANT FULL CREAM MILK POWDER LERY BRAND HS CODE CITIBANK 0.1697 5 FRED ROBERT FARMS LTD. MF0260096 379194 5,ODUSAMI STREET,MUSHIN,LAGOS 129.2000 2,090.00 271,617.68 DAY OLD HYBRO PS CHICKENS FBN 0.0036 6 CADBURY NIG PLC MF 0395286 RC 4151 LATEEF JAKANDE ROAD, AGIDINGBI, IKEJA, LAGOS 129.1500 7,452.54 279,070.22 IMPORTATION OF TUTTI FRUITTI FLAVOUR FSB 0.0127 7 ETCO NIGERIA LTD MF0214878 3457 14, CREEK ROAD APAPA LAGOS 129.1100 16,322.00 295,392.22 TRANSFORMER AFRI 0.0278 8 ETCO NIGERIA LTD MF0214196 3457 14, CREEK ROAD APAPA LAGOS 129.1100 17,968.19 313,360.41 CABLE TRAYS AFRI 0.0306 9 ETCO NIGERIA LTD MF0214884 3457 14, CREEK ROAD APAPA LAGOS 129.1100 18,500.00 331,860.41 BELDEN PVC GREY AFRI 0.0315 10 ETCO NIGERIA LIMITED MF 0408552 RC 3457 14 CREEK ROAD APAPA 129.1100 74,153.20 406,013.61 ELECTRICAL PANELS FUEL,PUMPS INSTALLATION TOOLS BOND 0.1261 11 ANGLO AFRICA AGENCIES (NIG) LTD MF0196760 3512 19, MARTINS STREET, 2ND FLOOR, CHARTERED 129.1100 5,321.75 411,335.36 HP CLEAR FILM ROLLS CITIBANK 0.0091 12 ENPEE INDUSTRIES PLC MF0188897 5909 19, MARTINS STREET, 2ND FLOOR, LAGOS. -

Conflict-Sensitive Journalism and the Nigerian Print Media Coverage of Jos Crisis, 2010-2011

CONFLICT-SENSITIVE JOURNALISM AND THE NIGERIAN PRINT MEDIA COVERAGE OF JOS CRISIS, 2010-2011. BY JIDE PETER JIMOH Matric No. 130129 B.SC, M.SC MASS COMMUNICATION (UNILAG), M.A. PEACE AND CONFLICT STUDIES (IBADAN) A thesis in Peace and Conflict Studies submitted to the Institute of African Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of the UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN LIBRARYMarch 2015 ABSTRACT The recent upsurge of crises in parts of Northern Nigeria has generated concerns in literature with specific reference to the role of the media in fuelling crises in the region. Previous studies on the Nigerian print media coverage of the Jos crisis focused on the obsolescent peace journalism perspective, which emphasises the suppression of conflict stories, to the neglect of the UNESCO Conflict-sensitive Journalism (CSJ) principles. These principles stress sensitivity in the use of language, coverage of peace initiatives, gender and other sensitivities, and the use of conflict analysis tools in reportage. This study, therefore, examined the extent to which the Nigerian print media conformed to these principles in the coverage of the Jos violent crisis between 2010 and 2011. The study adopted the descriptive research design and was guided by the theories of social responsibility, framing and hegemony. Content analysis of newspapers was combined with In-depth Interviews (IDIs) with 10 Jos-based journalists who covered the crisis. Four newspapers – The Guardian, The Punch, Daily Trust and National Standard were purposively selected over a period of two years (2010-2011) of the crisis. A content analysis coding schedule was developed to gather data from The Guardian (145 editions with 46 stories), The Punch (148 editions with 85 stories), Daily Trust (148 editions with 223 stories) and National Standard (132 editions with 187 stories) totalling 573 editions which yielded 541 stories for the analysis. -

Facts and Figures About Niger State Table of Content

FACTS AND FIGURES ABOUT NIGER STATE TABLE OF CONTENT TABLE DESCRIPTION PAGE Map of Niger State…………………………………………….................... i Table of Content ……………………………………………...................... ii-iii Brief Note on Niger State ………………………………………................... iv-vii 1. Local Govt. Areas in Niger State their Headquarters, Land Area, Population & Population Density……………………................... 1 2. List of Wards in Local Government Areas of Niger State ………..…... 2-4 3. Population of Niger State by Sex and Local Govt. Area: 2006 Census... 5 4. Political Leadership in Niger State: 1976 to Date………………............ 6 5. Deputy Governors in Niger State: 1976 to Date……………………...... 6 6. Niger State Executive Council As at December 2011…........................ 7 7. Elected Senate Members from Niger State by Zone: 2011…........…... 8 8. Elected House of Representatives’ Members from Niger State by Constituency: 2011…........…...………………………… ……..……. 8 9. Niger State Legislative Council: 2011……..........………………….......... 9 10. Special Advisers to the Chief Servant, Executive Governor Niger State as at December 2011........…………………………………...... 10 11. SMG/SSG and Heads of Service in Niger State 1976 to Date….….......... 11 12. Roll-Call of Permanent Secretaries as at December 2011..….………...... 12 13. Elected Local Govt. Chairmen in Niger State as at December 2011............. 13 14. Emirs in Niger State by their Designation, Domain & LGAs in the Emirate.…………………….…………………………..................................14 15. Approximate Distance of Local Government Headquarters from Minna (the State Capital) in Kms……………….................................................. 15 16. Electricity Generated by Hydro Power Stations in Niger State Compare to other Power Stations in Nigeria: 2004-2008 ……..……......... 16 17. Mineral Resources in Niger State by Type, Location & LGA …………. 17 ii 18. List of Water Resources in Niger State by Location and Size ………....... 18 19 Irrigation Projects in Niger State by LGA and Sited Area: 2003-2010.…. -

Lagos State Poctket Factfinder

HISTORY Before the creation of the States in 1967, the identity of Lagos was restricted to the Lagos Island of Eko (Bini word for war camp). The first settlers in Eko were the Aworis, who were mostly hunters and fishermen. They had migrated from Ile-Ife by stages to the coast at Ebute- Metta. The Aworis were later reinforced by a band of Benin warriors and joined by other Yoruba elements who settled on the mainland for a while till the danger of an attack by the warring tribes plaguing Yorubaland drove them to seek the security of the nearest island, Iddo, from where they spread to Eko. By 1851 after the abolition of the slave trade, there was a great attraction to Lagos by the repatriates. First were the Saro, mainly freed Yoruba captives and their descendants who, having been set ashore in Sierra Leone, responded to the pull of their homeland, and returned in successive waves to Lagos. Having had the privilege of Western education and christianity, they made remarkable contributions to education and the rapid modernisation of Lagos. They were granted land to settle in the Olowogbowo and Breadfruit areas of the island. The Brazilian returnees, the Aguda, also started arriving in Lagos in the mid-19th century and brought with them the skills they had acquired in Brazil. Most of them were master-builders, carpenters and masons, and gave the distinct charaterisitics of Brazilian architecture to their residential buildings at Bamgbose and Campos Square areas which form a large proportion of architectural richness of the city. -

The Press and Politics in Nigeria: a Case Study of Developmental Journalism, 6 B.C

UIC School of Law UIC Law Open Access Repository UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship 1-1-1986 The Press and Politics in Nigeria: A Case Study of Developmental Journalism, 6 B.C. Third World L.J. 85 (1986) Michael P. Seng John Marshall Law School Gary T. Hunt Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael P. Seng & Gary T. Hunt, The Press and Politics in Nigeria: A Case Study of Developmental Journalism, 6 B. C. Third World L. J. 85 (1986). https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs/301 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PRESS AND POLITICS IN NIGERIA: A CASE STUDY OF DEVELOPMENTAL JOURNALISM MICHAEL P. SENG* GARY T. HUNT** I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................... 85 II. PREss FREEDOM IN NIGERIA 1850-1983 .................................. 86 A. The Colonial Period: 1850-1959 ....................................... 86 B. The First Republic: 1960-1965 ........................................ 87 C. Military Rule: 1966-1979 ............................................. 89 D. The Second Republic: 1979-1983 ...................................... 90 III. THE THEORETICAL FOUNDATION FOR NIGERIAN PRESS FREEDOM: 1850- 1983 ..................................................................... 92 IV. TOWARD A NEw RoLE FOR THE PRESS IN NIGERIA? ....................... 94 V. THE THIRD WORLD CRITIQUE OF THE WESTERN VIEW OF THE ROLE OF THE PRESS .................................................................... 98 VI. DEVELOPMENTAL JOURNALISM: AN ALTERNATIVE TO THE WESTERN VIEW OF THE ROLE OF THE PRESS .............................................. -

The Press and Politics in Nigeria: a Case Study of Developmental Journalism, 6 B.C

Boston College Third World Law Journal Volume 6 | Issue 2 Article 1 6-1-1986 The rP ess and Politics in Nigeria: A Case Study of Developmental Journalism Michael P. Seng Gary T. Hunt Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/twlj Part of the African Studies Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Politics Commons Recommended Citation Michael P. Seng and Gary T. Hunt, The Press and Politics in Nigeria: A Case Study of Developmental Journalism, 6 B.C. Third World L.J. 85 (1986), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/twlj/vol6/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Third World Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PRESS AND POLITICS IN NIGERIA: A CASE STUDY OF DEVELOPMENTAL JOURNALISM MICHAEL P. SENG* GARY T. HUNT** I. INTRODUCTION........................................................... 85 II. PRESS FREEDOM IN NIGERIA 1850-1983 .................................. 86 A. The Colonial Period: 1850-1959....................................... 86 B. The First Republic: 1960-1965 . 87 C. Military Rule: 1966-1979............................................. 89 D. The Second Republic: 1979-1983...................................... 90 III. THE THEORETICAL FOUNDATION FOR NIGERIAN PRESS FREEDOM: 1850- 1983..................................................................... 92 IV. TOWARD A NEW ROLE FOR THE PRESS IN NIGERIA?...................... 94 V. THE THIRD WORLD CRITIQUE OF THE WESTERN VIEW OF THE ROLE OF THE PRESS.................................................................... 98 VI. DEVELOPMENTAL JOURNALISM: AN ALTERNATIVE TO THE WESTERN VIEW OF THE ROLE OF THE PRESS. -

Solving the Problem of Generation of Road Network Database for Minna and Environs Using Surveying and Geoinformatics Techniques

IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT) e-ISSN: 2319-2402,p- ISSN: 2319-2399.Volume 9, Issue 3 Ver. III (Mar. 2015), PP 01-06 www.iosrjournals.org Solving the Problem of Generation of Road Network Database for Minna and Environs Using Surveying and Geoinformatics Techniques Onuigbo, Ifeanyi Chukwudi Department of Surveying and Geoinformatics, School of Environmental Technology, Federal University of Technology P.M.B. 65 Minna. Niger State, NIGERIA. Abstract: Roads are very important. Road network database of an area is also very important. A good road infrastructure is an essential basis for economic development. The study Area is Minna and environs. The study is aimed at creating road network database for Minna and environs. The objectives are to use GIS, Remote Sensing and Surveying techniques to gather data and create the road network database of the study area. Satellite images and existing road map of the study area were used. The satellite image was used to carry out field survey. ArcMap 9.2 software was used to digitize the road network. Road names were identified from the field survey. Then the creation or generation of road network database for the study area was done. In the database are the names of the roads identified in the study area and their types. Keywords: Road network, Database, Satellite images, Database management, Geoinformatics. I. Introduction A road is a specially prepared way, publicly or privately owned, between places for the use of pedestrians, riders, vehicles, etc.(Hornby, 2005). A road network system in any area provides a means of transportation of goods, services and interaction of individuals. -

The Politics of News Reportage And

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF NEWS REPORTAGE AND PRESENTATION OF NEWS IN NIGERIA: A STUDY OF TELEVISION NEWS BY IGOMU ONOJA B.Sc, M.Sc (Jos). (PGSS/UJ/12674/00) A Thesis in the DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY, Faculty of Social Sciences, Submitted to the School of Postgraduate Studies, UNIVERSITY OF JOS, JOS, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D) of the UNIVERSITY OF JOS. August 2005 ii DECLARATION I, hereby declare that this work is the product of my own research efforts, undertaken under the supervision of Prof. Ogoh Alubo, and has not been presented elsewhere for an award of a degree or certificate. All sources have been duly distinguished and appropriately acknowledged IGOMU ONOJA PGSS/UJ/12674/00 iii CERTIFICATION iv DEDICATION To my wife, Ada, for all her patience while I was on the road most of the time. v ACKNOWLEDEGEMENTS I am most grateful to Professor Ogoh Alubo who ensured that this research work made progress. He almost made it a personal challenge ensuring that all necessary references and corrections were made. His wife also made sure that I was at home any time I visited Jos. Their love and concern for this work has been most commendable. My brother, and friend, Dr. Alam’ Efihraim Idyorough of the Sociology Department gave all necessary advice to enable me reach this stage of the research. He helped to provide reference materials most times, read through the script, and offered suggestions. The academic staff of Sociology Department and the entire members of the Faculty of Social Sciences assisted in many ways when I made presentations. -

Investment Policy Review of Nigeria

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT INVESTMENT POLICY REVIEW NIGERIA UNITED NATIONS United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Investment Policy Review Nigeria UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2009 I Investment Policy Review of Nigeria NOTE UNCTAD serves as the focal point within the United Nations Secretariat for all matters related to foreign direct investment. This function was formerly carried out by the United Nations Centre on Transnational Corporations (1975-1992). UNCTAD’s work is carried out through intergovernmental deliberations, research and analysis, technical assistance activities, seminars, workshops and conferences. The term “country” as used in this study also refers, as appropriate, to territories or areas; the designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. In addition, the designations of country groups are intended solely for statistical or analytical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgement about the stage of development reached by a particular country or area in the development process. The following symbols have been used in the tables: Two dots (..) indicate that date are not available or not separately reported. Rows in tables have been omitted in those cases where no data are available for any of the elements in the row. A dash (-) indicates that the item is equal to zero or its value is negligible. A blank in a table indicates that the item is not applicable.