Ademy Arrow Academy Arrow Academy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 20, 2017 Movie Year STAR 351 P Acu Lan E, Bish Op a B Erd

Movie Year STAR 351 Pacu Lane, Bishop Aberdeen Aberdeen Restaurant, Olancha Airflite Diner, Alabama Hills Ranch Anchor Alpenhof Lodge, Mammoth Lakes Benton Crossing Big Pine Bishop Bishop Reservation Paiute Buttermilk Country Carson & Colorado Railroad Gordo Cerro Chalk Bluffs Inyo Convict Lake Coso Junction Cottonwood Canyon Lake Crowley Crystal Crag Darwin Deep Springs Big Pine College, Devil's Postpile Diaz Lake, Lone Pine Eastern Sierra Fish Springs High Sierras High Sierra Mountains Highway 136 Keeler Highway 395 & Gill Station Rd Hoppy Cabin Horseshoe Meadows Rd Hot Creek Independence Inyo County Inyo National Forest June Lake June Mountain Keeler Station Keeler Kennedy Meadows Lake Crowley Lake Mary 2012 Gold Rush Expedition Race 2013 DOCUMENTARY 2013 Gold Rush Expedition Race 2014 DOCUMENTARY 2014 Gold Rush Expedition Race 2015 DOCUMENTARY 26 Men: Incident at Yuma 1957 Tristram Coffin x 3 Bad Men 1926 George O'Brien x 3 Godfathers 1948 John Wayne x x 5 Races, 5 Continents (SHORT) 2011 Kilian Jornet Abandoned: California Water Supply 2016 Rick McCrank x x Above Suspicion 1943 Joan Crawford x Across the Plains 1939 Jack Randall x Adventures in Wild California 2000 Susan Campbell x Adventures of Captain Marvel 1941 Tom Tyler x Adventures of Champion, The 1955-1956 Champion (the horse) Adventures of Champion, The: Andrew and the Deadly Double1956 Champion the Horse x Adventures of Champion, The: Crossroad Trail 1955 Champion the Horse x Adventures of Hajji Baba, The 1954 John Derek x Adventures of Marco Polo, The 1938 Gary Cooper x Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok 1951-1958 Guy Madison Affairs with Bears (SHORT) 2002 Steve Searles Air Mail 1932 Pat O'Brien x Alias Smith and Jones 1971-1973 Ben Murphy x Alien Planet (TV Movie) 2005 Wayne D. -

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

MASCULINITY AS SPECTACLE REFLECTIONS on MEN and MAINSTREAM CINEMA by STEVE NEALE Downloaded From

MASCULINITY AS SPECTACLE REFLECTIONS ON MEN AND MAINSTREAM CINEMA BY STEVE NEALE Downloaded from http://screen.oxfordjournals.org/ OVER THE PAST ten years or so, numerous books and articles 1 Laura Mulvey, have appeared discussing the images of women produced and circulated 'Visual Pleasure by the cinematic institution. Motivated politically by the development and Narrative Cinema', Screen of the Women's Movement, and concerned therefore with the political Autumn 1975, vol and ideological implications of the representations of women offered by at Illinois University on July 18, 2014 16 no 3, pp 6-18. the cinema, a number of these books and articles have taken as their basis Laura Mulvey's 'Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema', first published in Screen in 1975'. Mulvey's article was highly influential in its linking together of psychoanalytic perspectives on the cinema with a feminist perspective on the ways in which images of women figure within main- stream film. She sought to demonstrate the extent to which the psychic mechanisms cinema has basically involved are profoundly patriarchal, and the extent to which the images of women mainstream film has produced lie at the heart of those mechanisms. Inasmuch as there has been discussion of gender, sexuality, represen- tation and the cinema over the past decade then, that discussion has tended overwhelmingly to centre on the representation of women, and to derive many of its basic tenets from Mulvey^'s article. Only within the Gay Movement have there appeared specific discussions of the represen- tation of men. Most of these, as far as I am aware, have centred on the representations and stereotypes of gay men. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

The Naked Spur: Classic Western Scores from M-G-M

FSMCD Vol. 11, No. 7 The Naked Spur: Classic Western Scores From M-G-M Supplemental Liner Notes Contents The Naked Spur 1 The Wild North 5 The Last Hunt 9 Devil’s Doorway 14 Escape From Fort Bravo 18 Liner notes ©2008 Film Score Monthly, 6311 Romaine Street, Suite 7109, Hollywood CA 90038. These notes may be printed or archived electronically for personal use only. For a complete catalog of all FSM releases, please visit: http://www.filmscoremonthly.com The Naked Spur ©1953 Turner Entertainment Co., A Warner Bros. Entertainment Company. The Wild North ©1952 Turner Entertainment Co., A Warner Bros. Entertainment Company. The Last Hunt ©1956 Turner Entertainment Co., A Warner Bros. Entertainment Company. Devil’s Doorway ©1950 Turner Entertainment Co., A Warner Bros. Entertainment Company. Escape From Fort Bravo ©1953 Turner Entertainment Co., A Warner Bros. Entertainment Company. All rights reserved. FSMCD Vol. 11, No. 7 • Classic Western Scores From M-G-M • Supplemental Liner Notes The Naked Spur Anthony Mann (1906–1967) directed films in a screenplay” and The Hollywood Reporter calling it wide variety of genres, from film noir to musical to “finely acted,” although Variety felt that it was “proba- biopic to historical epic, but today he is most often ac- bly too raw and brutal for some theatergoers.” William claimed for the “psychological” westerns he made with Mellor’s Technicolor cinematography of the scenic Col- star James Stewart, including Winchester ’73 (1950), orado locations received particular praise, although Bend of the River (1952), The Far Country (1954) and The several critics commented on the anachronistic appear- Man From Laramie (1955). -

James Stewart: the Trouble with Urban Modernity in Verligo and Liberly Valance

MA MAJOR RESEARCH PAPER James Stewart: The Trouble with Urban Modernity in Verligo and Liberly Valance ALEX MORRIS Supervisor: Edward Siopek The Major Research Paper is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Joint Graduate Program in Communication & Culture Ryerson University - York University Toronto, Ontario, Canada Sept. 21, 2009 Table of Contents Introduction: Post-War Stewart and the Dark Turn in Hollywood ...................................... 2 Chapter 1: Vertigo: An Architecture for Double Vision ..................................................... 13 Chapter 2: Liberty Valance: Masculine Anxiety in the Cinematic "Wild West" ................ 24 Works Cited and Consulted .............................................................................44 1 Introduction Legendary 20th Century Hollywood film star and American everyman James Maitland Stewart saw merit and enduring intrinsic reward more in his extensive career as a decorated military serviceman, which began a year before Pearl Harbor, well before his nation joined the fighting in the European theatre of the Second World War, and ended long after his controversial peace-time promotion to Brigadier General decades later than in his lifelong career as a cherished and profoundly successful screen actor. For him, as for his father and grandfather before him, who, between the two of them, saw action in three major American wars, serving the nation militarily was as good as it got. When asked by an interviewer some 50 years after the end of his wartime military service about his WWII memories, writes biographer Jonathan Coe in his book, Jimmy Stewart: A Wonderful Life, Stewart remarks that his military experience was "something that I think about almost everyday: one of the greatest experiences of my life." "Greater than being in the movies?" countered the reporter. -

Curriculum Vitae: Dr. Ken Coates

Curriculum Vitae: Dr. Ken Coates Address: 903B – 9th Street East Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7H 0M9 306 341 0545 (Cell) University of Saskatchewan Address: Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy Room 181, 101 Diefenbaker Place University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5B8 1 306 966 5136 (office) [email protected] University Degrees Bachelor of Arts (History), University of British Columbia, 1978 Master of Arts (History), University of Manitoba, 1980. PhD (History), University of British Columbia, 1984. Dissertation: “Best Left As Indians: Native-White Relations in the Yukon Territory, 1840-1950.” Supervisor Dr. David Breen. Academic and Professional Positions Canada Research Chair in Regional Innovation, Johnson-Showama Graduate School of Public Policy, University of Saskatchewan, 2012 – Professor of History, University of Waterloo, 2011-2012 Dean, Faculty of Arts, and Professor, Department of History, University of Waterloo, 2006-2011 Coates Holroyd Consulting, Garibaldi Highlands, B.C., 2004 – Vice-President (Academic), Sea to Sky University, Squamish, B.C., 2004 Dean, College of Arts and Science, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, 2001-2004. Acting Provost and Vice-President (Academic), University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, 2002-2003. Dean, Faculty of Arts and Professor of History, University of New Brunswick at Saint John, Saint John, New Brunswick, July 1997-2000. Professor of History and Chair, Department of History, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand, 1995-1997. Vice-President (Academic) and Professor of History, University of Northern British Columbia, Prince George, B.C., 1992-1995. Professor, Department of History, University of Victoria, Victoria, B.C., 1986-1992. Associate Professor, Department of History, Brandon University, Brandon, Manitoba, 1983-1986. -

J'essaie Toujours De Construire Mes Films Sur

Contempler est en effet pour Anthony Mann le but ul- time de la mise en scène western. Non qu’il n’ait de goût pour l’action et sa violence, sa cruauté même. Il sait au LES AFFAMEURS «contraire la faire éclater avec une soudaineté éblouissante mais nous sentons bien qu’elle déchire la paix et qu’elle as- UN FILM D’ANTHONY MANN pire à y retourner de même que les grands contemplatifs font les meilleurs hommes d’action parce qu’ils en mesurent tous ensemble la vanité dans la nécessité. » André Bazin 1952 - états-Unis - 91 min - Visa 12777 - vostf Version restaurée 2k SORTIE 20 FÉVRIER 2019 DISTRIBUTION MARY-X DISTRIBUTION PRESSE 308 rue de Charenton 75012 Paris SF EVENTS Tel : 01 71 24 23 04 / 06 84 86 40 70 Tél : 07 60 29 18 10 [email protected] [email protected] SYNOPSIS Deux hommes au passé trouble, Glyn McLyntock et son ami Emerson Cole, escortent la longue marche d’un convoi de pionniers. Arrivés à Portland, les fermiers achètent des vivres et du bétail que Hendricks, un né- gociant de la ville, promet d’envoyer avant l’automne. Les mois passent et la livraison se fait attendre... beaucoup plus ambigus que les archétypes universels de John Ford. C’est le cas de James Stewart dans Les Affameurs (le premier film en couleur de Mann) et de Gary Cooper dans L’Homme de l’Ouest. Avec Winchester 73, il entame une fructueuse col- laboration avec le scénariste Borden Chase, collaboration qui s’achèvera en 1955 et 5 films plus tard avec L’Homme de la plaine. -

THE DARK PAGES the Newsletter for Film Noir Lovers Vol

THE DARK PAGES The Newsletter for Film Noir Lovers Vol. 6, Number 1 SPECIAL SUPER-SIZED ISSUE!! January/February 2010 From Sheet to Celluloid: The Maltese Falcon by Karen Burroughs Hannsberry s I read The Maltese Falcon, by Dashiell Hammett, I decide on who will be the “fall guy” for the murders of Thursby Aactually found myself flipping more than once to check and Archer. As in the book, the film depicts Gutman giving Spade the copyright, certain that the book couldn’t have preceded the an envelope containing 10 one-thousand dollar bills as a payment 1941 film, so closely did the screenplay follow the words I was for the black bird, and Spade hands it over to Brigid for safe reading. But, to be sure, the Hammett novel was written in 1930, keeping. But when Brigid heads for the kitchen to make coffee and the 1941 film was the third of three features based on the and Gutman suggests that she leave the cash-filled envelope, he book. (The first, released in 1931, starred Ricardo Cortez and announces that it now only contains $900. Spade immediately Bebe Daniels, and the second, the 1936 film, Satan Met a Lady, deduces that Gutman palmed one of the bills and threatens to was a light comedy with Warren William and Bette Davis.) “frisk” him until the fat man admits that Spade is correct. But For my money, and for most noirists, the 94 version is the a far different scene played out in the book where, when the definitive adaptation. missing bill is announced, Spade ushers Brigid The 1941 film starred Humphrey Bogart into the bathroom and orders her to strip naked as private detective Sam Spade, along with to prove her innocence. -

Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema

PERFORMING ARTS • FILM HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF Historical Dictionaries of Literature and the Arts, No. 26 VARNER When early filmgoers watched The Great Train Robbery in 1903, many shrieked in terror at the very last clip, when one of the outlaws turned toward the camera and seemingly fired a gun directly at the audience. The puff of WESTERNS smoke was sudden and hand-colored, and it looked real. Today we can look back at that primitive movie and see all the elements of what would evolve HISTORICAL into the Western genre. Perhaps the Western’s early origins—The Great Train DICTIONARY OF Robbery was the first narrative, commercial movie—or its formulaic yet enter- WESTERNS in Cinema taining structure has made the genre so popular. And with the recent success of films like 3:10 to Yuma and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, the Western appears to be in no danger of disappearing. The story of the Western is told in this Historical Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema through a chronology, a bibliography, an introductory essay, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries on cinematographers; com- posers; producers; films like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Dances with Wolves, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, High Noon, The Magnificent Seven, The Searchers, Tombstone, and Unforgiven; actors such as Gene Autry, in Cinema Cinema Kirk Douglas, Clint Eastwood, Henry Fonda, Jimmy Stewart, and John Wayne; and directors like John Ford and Sergio Leone. PAUL VARNER is professor of English at Abilene Christian University in Abilene, Texas. -

The Webfooter

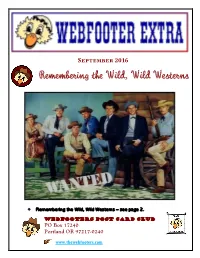

September 2016 Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns – see page 2. Webfooters Post Card Club PO Box 17240 Portland OR 97217-0240 www.thewebfooters.com Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns Before Batman, before Star Trek and space travel to the moon, Westerns ruled prime time television. Warner Brothers stable of Western stars included (l to r) Will Hutchins – Sugarfoot, Peter Brown – Deputy Johnny McKay in Lawman, Jack Kelly – Bart Maverick, Ty Hardin – Bronco, James Garner – Bret Maverick, Wade Preston – Colt .45, and John Russell – Marshal Dan Troupe in Lawman, circa 1958. Westerns became popular in the early years of television, in the era before television signals were broadcast in color. During the years from 1959 to 1961, thirty-two different Westerns aired in prime time. The television stars that we saw every night were larger than life. In addition to the many western movie stars, many of our heroes and role models were the western television actors like John Russell and Peter Brown of Lawman, Clint Walker on Cheyenne, James Garner on Maverick, James Drury as the Virginian, Chuck Connors as the Rifleman and Steve McQueen of Wanted: Dead or Alive, and the list goes on. Western movies that became popular in the 1940s recalled life in the West in the latter half of the 19th century. They added generous doses of humor and musical fun. As western dramas on radio and television developed, some of them incorporated a combination of cowboy and hillbilly shtick in many western movies and later in TV shows like Gunsmoke. -

Glorious Technicolor: from George Eastman House and Beyond Screening Schedule June 5–August 5, 2015 Friday, June 5 4:30 the G

Glorious Technicolor: From George Eastman House and Beyond Screening Schedule June 5–August 5, 2015 Friday, June 5 4:30 The Garden of Allah. 1936. USA. Directed by Richard Boleslawski. Screenplay by W.P. Lipscomb, Lynn Riggs, based on the novel by Robert Hichens. With Marlene Dietrich, Charles Boyer, Basil Rathbone, Joseph Schildkraut. 35mm restoration by The Museum of Modern Art, with support from the Celeste Bartos Fund for Film Preservation; courtesy The Walt Disney Studios. 75 min. La Cucaracha. 1934. Directed by Lloyd Corrigan. With Steffi Duna, Don Alvarado, Paul Porcasi, Eduardo Durant’s Rhumba Band. Courtesy George Eastman House (35mm dye-transfer print on June 5); and UCLA Film & Television Archive (restored 35mm print on July 21). 20 min. [John Barrymore Technicolor Test for Hamlet]. 1933. USA. Pioneer Pictures. 35mm print from The Museum of Modern Art. 5 min. 7:00 The Wizard of Oz. 1939. USA. Directed by Victor Fleming. Screenplay by Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson, Edgar Allan Woolf, based on the book by L. Frank Baum. Music by Harold Arlen, E.Y. Harburg. With Judy Garland, Frank Morgan, Ray Bolger, Bert Lahr, Ray Bolger, Margaret Hamilton, Billie Burke. 35mm print from George Eastman House; courtesy Warner Bros. 102 min. Saturday, June 6 2:30 THE DAWN OF TECHNICOLOR: THE SILENT ERA *Special Guest Appearances: James Layton and David Pierce, authors of The Dawn of Technicolor, 1915-1935 (George Eastman House, 2015). James Layton and David Pierce illustrate Technicolor’s origins during the silent film era. Before Technicolor achieved success in the 1930s, the company had to overcome countless technical challenges and persuade cost-conscious producers that color was worth the extra effort and expense.