Why Not Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Old Photos of Tower Hamlets

Caught on camera! – Using film and Historical photos might be useful if you want to compare your study area with what it used to be like –Even photos from a few years ago can show photographs as secondary sources stark contrasts in terms of rebranding/ gentrification etc Excerpt from the ALCAB report 2014 (on which the A Level specifications are based) Human Geography: Changing places - Meaning and Representation Meaning and representation relates to how humans perceive, engage with and form attachments to the world. This might be the everyday meanings that humans attach to places bound up with a sense of identity and belonging. It also extends to ways that meanings of place might be created, such as through place making and marketing. Representations of places are important because of the way in which they shape peoples' actions and behaviours, and those of businesses, institutions and governments. Representations also provide a reference point for people's sense of identity, underpinning their attachments to place, particularly in times of change. Attention to meaning highlights the processes of representation through which places are depicted, variously by external agencies and by those who live in them. The meanings and identities ascribed to a place may also be related to its function, both social and economic, in the present and in the past. Places can have multiple meanings and identities, reflecting different perceptions and perspectives. Students should select one of the following topics through which to address the concepts of meaning and representation as applied to place: Place making and marketing, drawing on examples such as regional development agencies, tourist marketing, and property marketing materials. -

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

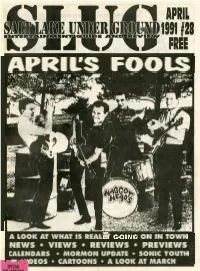

April's Fools

APRIL'S FOOLS ' A LOOK AT WHAT IS REAL f ( i ON IN. TOWN NEWS VIEWS . REVIEWS PREVIEWS CALENDARS MORMON UPDATE SONIC YOUTH -"'DEOS CARTOONS A LOOK AT MARCH frlday, april5 $7 NOMEANSNO, vlcnms FAMILYI POWERSLAVI saturday, april 6 $5 an 1 1 piece ska bcnd from cdlfomb SPECKS witb SWlM HERSCHEL SWIM & sunday,aprll7 $5 from washln on d.c. m JAWBO%, THE STENCH wednesday, aprl10 KRWTOR, BLITZPEER, MMGOTH tMets $10raunch, hemmetal shoD I SUNDAY. APRIL 7 I INgTtD, REALITY, S- saturday. aprll $5 -1 - from bs aqdes, califomla HARUM SCAIUM, MAG&EADS,;~ monday. aprlll5 free 4-8. MAtERldl ISSUE, IDAHO SYNDROME wedn apri 17 $5 DO^ MEAN MAYBE, SPOT fiday. am 19 $4 STILL UFEI ALCOHOL DEATH saturday, april20 $4 SHADOWPLAY gooah TBA mday, 26 Ih. rlrdwuhr tour from a land N~AWDEATH, ~O~LESH;NOCTURNUS tickets $10 heavy metal shop, raunch MATERIAL ISSUE I -PRIL 15 I comina in mayP8 TFL, TREE PEOPLE, SLaM SUZANNE, ALL, UFT INSANE WARLOCK PINCHERS, MORE MONDAY, APRIL 29 I DEAR DICKHEADS k My fellow Americans, though:~eopledo jump around and just as innowtiwe, do your thing let and CLIJG ~~t of a to NW slam like they're at a punk show. otherf do theirs, you sounded almost as ENTEIWAINMENT man for hispoeitivereviewof SWIM Unfortunately in Utah, people seem kd as L.L. "Cwl Guy" Smith. If you. GUIIBE ANIB HERSCHELSWIMsdebutecassette. to think that if the music is fast, you are that serious, I imagine we will see I'mnotamemberofthebancljustan have to slam, but we're doing our you and your clan at The Specks on IMVIEW avid ska fan, and it's nice to know best to teach the kids to skank cor- Sahcr+nightgiwingskrmkin'Jessom. -

Infamous British Criminals Lesson Plan

My FavouritesInfamous British Criminals Lesson Plan Lesson Pl By Louise Delahay Warm-Up (10 minutes) Ask the class What British criminals have you heard of? Tell them that these could be figures from history. Welcome all suggestions. Ask students to tell the class what they know about any of these criminals.. Reading Practice (10 minutes) Tell students they are going to read a text about four infamous British criminals. They should read the text quickly first and answer the question. Did the earlier lives of the men indicate that they would later become criminals? Check with the class. Answer Key: Dick Turpin – yes; the Kray Twins – to some extent; Guy Fawkes – no Ask students to answer the questions which follow the reading text individually. When they have finished compare answers as a whole class. Check with the answer key. Photocopiable © Pearson Italia Grammar Focus (10 minutes) Write the following examples on the board and ask the questions: Prior to their conviction, the brothers had owned a snooker club. What is the tense used? Why this tense? Answer: Past perfect, because it refers to an event which happened before the time in the past being described (draw this diagram for the students if it’s useful) Future Future owned a snooker club PASTPAST convicted Present n He had been guarding the gunpowder when he was discovered. What is this tense? Why is it used? Answer: Past perfect continuous, because it describes a longer action which was being done up to the point in the past being described. PAST Future guarding the gunpowder Guy Fawkes was discovered Present Elicit the form: past perfect = had + past participle past perfect continuous = had been + present participle (-ing) You can also note that sometimes, when two past events are described in the order in which they happened, the second example does not generally need to use past perfect. -

Voting Problems Cause Halt in Honor Council Elections the Ballot Itself

Freshman phenom Administration wants Tribe baseball opens Quinn McDowell fraternities gone season with 3 wins SEE BACK PAGE SEE PAGE 4 SEE BACK PAGE The twice-weekly student newspaper of the College of William and Mary — Est. 1911 VOL.98, NO.35 TUESDAY, FEBRuaRY 24, 2009 FLATHATNEWS.COM HITTING THE LINKS Voting problems cause halt in Honor Council elections the ballot itself. Glitches force council From the opening of voting at 8 a.m., members of the Honor Council and the Student Assembly to move referendum were flooded with complaints from students expe- riencing difficulties casting their ballots. to Wednesday Honor Council Elections Committee By IAN BRICKEY Chairman Will Eaton VOTE WEDNESDAY The referendum and Flat Hat Staff Writer ’09 said the initial problem was caused election vote will take place College of William and Mary administrators by transferring the Wednesday between postponed Monday’s referendum on possible ballot’s Word docu- 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. online changes to the Honor Code, along with the elec- ment to a web site. via Opinio. tion of members to the Undergraduate Honor “The text of the Council. A new election will be held Wednesday referendum was from Microsoft Word,” Eaton due to the technical problems. said. “We could view it while we were editing it, “We apologize for the technical difficulties but when some people accessed it, the script actu- concerning today’s Honor Council Elections and ally expanded and covered the choices, and stu- Honor Code Revision,” the Honor Council said in dents weren’t able to vote.” a statement to students sent through Interim Vice- Another technical difficulty involved the web President for Student Affairs Ginger Ambler ’88 addresses that were e-mailed to students. -

Partyman by Title

Partyman by Title #1 Crush (SCK) (Musical) Sound Of Music - Garbage - (Musical) Sound Of Music (SF) (I Called Her) Tennessee (PH) (Parody) Unknown (Doo Wop) - Tim Dugger - That Thing (UKN) 007 (Shanty Town) (MRE) Alan Jackson (Who Says) You - Can't Have It All (CB) Desmond Decker & The Aces - Blue Oyster Cult (Don't Fear) The - '03 Bonnie & Clyde (MM) Reaper (DK) Jay-Z & Beyonce - Bon Jovi (You Want To) Make A - '03 Bonnie And Clyde (THM) Memory (THM) Jay-Z Ft. Beyonce Knowles - Bryan Adams (Everything I Do) I - 1 2 3 (TZ) Do It For You (SCK) (Spanish) El Simbolo - Carpenters (They Long To Be) - 1 Thing (THM) Close To You (DK) Amerie - Celine Dion (If There Was) Any - Other Way (SCK) 1, 2 Step (SCK) Cher (This Is) A Song For The - Ciara & Missy Elliott - Lonely (THM) 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) (CB) Clarence 'Frogman' Henry (I - Plain White T's - Don't Know Why) But I Do (MM) 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New (SF) Cutting Crew (I Just) Died In - Coolio - Your Arms (SCK) 1,000 Faces (CB) Dierks Bentley -I Hold On (Ask) - Randy Montana - Dolly Parton- Together You And I - (CB) 1+1 (CB) Elvis Presley (Now & Then) - Beyonce' - There's A Fool Such As I (SF) 10 Days Late (SCK) Elvis Presley (You're So Square) - Third Eye Blind - Baby I Don't Care (SCK) 100 Kilos De Barro (TZ) Gloriana (Kissed You) Good - (Spanish) Enrique Guzman - Night (PH) 100 Years (THM) Human League (Keep Feeling) - Five For Fighting - Fascination (SCK) 100% Pure Love (NT) Johnny Cash (Ghost) Riders In - The Sky (SCK) Crystal Waters - K.D. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Jeremyt Morrissey, Johnny Marr and the Smiths in London 1. Home to A

Author: JeremyT Morrissey, Johnny Marr and The Smiths in London 1. Home to a Mozzer, Regent's Park Terrace, Camden Mozzer lived on this street in the 90s... but which number? Notes: 2. Morrissey & Marr call time, 2 Farmer Street, London Johnny Marr called a Smiths meeting here to leave the band Notes: 3. Pop Video Morrissey Style, Lyndhurst Hall, Warden Road Sing Your Life was filmed here with help from Chrissie Hynde Notes: 4. Ridgeway House's Musical History, Runwick Lane, Farnham, Surrey Former recording studio of choice to the stars. Notes: 5. The Beeb rocks Out!, 2-22 Portland Place Home to legendary performances from the likes of Moz Notes: 6. Morrissey Lived Here..., Campden Hill Road, Kensington He did indeed, on this road, but can you tell us the number? Notes: 7. Moz and the Suedehead House, 32 Chester Square Mozzer seen here sometime in 1987/88 recording a superb video Notes: 8. A Post made famous by Morrissey, Tench Street / Reardon Street Mozzer and Post can be seen on the 'Bona Drag' album artwork Notes: www.shadyoldlady.com Page 1/2 9. Geoff Travis calls Johnny Marr, Blenheim Crescent, Marr & Rourke blagged their way in get The Smiths signed Notes: 10. Mary Poppins author lived here, 50 Smith Street, Chelsea The home and inspiration behind Mary Poppins. Notes: 11. Dirk Bogarde does Chelsea, 30 Royal Avenue, off King's Road Home to 'The Servant' starring Dirk Bogarde back in 1963 Notes: 12. Brixton Academy & The Smiths, 211 Stockwell Road The Smiths last ever gig took place here in 1986 Notes: www.shadyoldlady.com Page 2/2. -

The Carroll News

John Carroll University Carroll Collected The aC rroll News Student 11-8-2007 The aC rroll News- Vol. 84, No. 8 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "The aC rroll News- Vol. 84, No. 8" (2007). The Carroll News. 758. http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews/758 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC rroll News by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Men’s soccer American Gangster wins O.A.C. CN review of the newly Soccer team makes the released hit. Arts & Life, championship round. p. 6 Sports, p. 14 THE ARROLL EWS Thursday,C November 8, 2007 Serving John Carroll University Since 1925N Vol. 84, No. 8 Sexual City Council bill affects assault reported Max Flessner JCU off-campus renters Campus Editor Max Flessner Campus Editor A female John Carroll Univer- Highlights of the proposed ordinance sity student reported that she was University Heights City Council sexually assaulted on campus by a unveiled legislation last Monday non-JCU acquaintance early on the night that could have a significant morning of Oct. 27. impact on John Carroll Univer- Unlike many of the previously sity students who rent property off reported sexual assaults at JCU, this campus. incident occurred outdoors. Campus Four proposed ordinances were Safety Services and the University introduced that gives the city the Heights Police Department were ability to revoke a renters permit to immediately notified and the suspect a landlord. -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

Merkitysten Verkko Faniuden Diskursseja Pop-Tähti Morrisseyta Käsittelevän Sivuston Keskusteluissa

Merkitysten verkko Faniuden diskursseja pop-tähti Morrisseyta käsittelevän sivuston keskusteluissa Antti Haavisto Musiikintutkimuksen pro gradu -tutkielma Viestintätieteiden tiedekunta Tampereen yliopisto Joulukuu 2017 TAMPEREEN YLIOPISTO Viestintätieteiden tiedekunta HAAVISTO, ANTTI: MERKITYSTEN VERKKO. Faniuden diskursseja pop-tähti Morrisseyta käsittelevän sivuston keskusteluissa. Pro gradu -tutkielma, 76 s. Musiikintutkimus Joulukuu 2017 Tarkastelen pro gradu -tutkielmassani pop-artisti Steven Morrisseyn faniyhteisön toimintaa tälle omistetulla fanisivustolla osoitteessa www.morrissey-solo.com. Pyrin selvittämään minkälaisia diskursseja sivuston keskustelufoorumilla käydyt keskustelut sisältävät ja millaisia faniuden kategorioita keskusteluissa on mahdollista havaita. Tämän lisäksi pohdin sitä, miten entistä interaktiivisemmaksi muuttuva mediaympäristö on vaikuttanut tähteyteen, fanien toimintaan ja faniuden käytäntöihin. Tutkimukseni pääasiallinen aineisto koostuu seitsemästä laajuudeltaan vaihtelevasta keskusteluketjusta fanisivuston keskustelufoorumilla. Olen kerännyt aineiston internet- etnografiana, jossa seurasin tämän faniyhteisön keskustelemisen tapoja ja käytänteitä osallistumatta kuitenkaan itse keskusteluun. Analysoin aineiston tekstipohjaisena diskurssianalyysina, erityisesti kategoria-analyysia työkaluna käyttäen. Tutkimani fanisivuston keskusteluissa on havaittavissa useita eri diskursseja ja faniuden kategorioita, jotka osittaisista päällekkäisyyksistä huolimatta poikkeavat toisistaan merkittävillä tavoilla. Erityisen -

Nibbler by Ken Urban

NIBBLER BY KEN URBAN DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. NIBBLER Copyright © 2017, Ken Urban All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of NIB- BLER is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation profes- sional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, elec- tronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for NIBBLER are controlled exclusively by Dra- matists Play Service, Inc., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No profes- sional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of Dramatists Play Service, Inc., and paying the requi- site fee. Inquiries concerning all other rights should be addressed to Abrams Artists Agency, 275 Seventh Avenue, 26th Floor, New York, NY 10001.