Colonial Contexts of Urban Space in Modern Japanese Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critical Race and Whiteness Studies

Critical Race and Whiteness Studies www.acrawsa.org.au/ejournal Volume 10, Number 2, 2014 10th ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL ISSUE OF CRITICAL RACE AND WHITENESS STUDIES The taxonomic gaze: Looking at whiteness from east to west Vera Mackie University of Wollongong In this article I consider representations of whiteness which emanate from outside the Euro-American centres. I argue that it is necessary to understand how whiteness has been seen by non-white observers, and that we need to be sensitive to local taxonomies of difference which are not always reducible to the white/non-white distinction which is hegemonic in the Euro-American centres. I consider the works of some artists and writers from early twentieth century Japan who are sensitive to their positioning in international hierarchies and who attempt to place themselves in a position of power in these gendered, classed, ethnicised and racialised hierarchies through their deployment of what I call the ‘taxonomic gaze’. I argue that the concept of whiteness needs to be historicised and provincialised, and that the field of whiteness studies itself also needs to be historicised. Keywords: whiteness, racialisation, Japan, taxonomic gaze Introduction In 1921, I left Japan and headed for France. The ship had hardly docked in Shanghai before my fellow passengers, from curiosity to know a Western woman, went to visit the white-walled western building with the red light. There they were taken by the golden hair of the Polish Jewish women and the Russian refugee women, enchanted by the charm of blue eyes, and returned to the ship singing paeans. -

Modern Japanese Literature

College of Arts and Sciences Department of Modern Languages and Literatures Oakland University JPN 420 Japanese Literature –Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, 4 credits Winter 2010 Course Catalogue Description: Reading texts of various genres. Conducted in Japanese. Prerequisites: JPN 314, 318 and 355. Sensei: Seigo Nakao, PhD Office: 354 O’Dowd Hall. Office Hours: MWF: 2:30-3:30. Or by appointment. Office Phone: (248) 370-2066. Email address: [email protected] This class satisfies the General Education requirement for the Capstone Experience in the Major. Satisfies the university general education requirement for a Writing Intensive in the Major. Prerequisites for the writing intensive: JPN 314, 318, and 355; also, completion of the university writing foundation requirement. General Education Learning Outcomes: Integration Knowledge Area: As a capstone course, The student will demonstrate: - appropriate uses of a variety of methods of inquiry (through exposure to a variety of literary approaches via lectures and research) and a recognition of ethical considerations that arise (through discussions and written treatments [tests, research paper] of literary themes). - the ability to integrate the knowledge learned in general education (foreign language and culture, and literature) and its relevance to the student’s life and career. Knowledge Areas: 1. Foreign Language and Culture Students integrate the following ACTFL national standard skills in the Japanese language: speaking (class discussions), listening (lectures), reading (literary texts), culture and writing (tests, papers) in the context of Japanese literature. 2. Literature Students will develop and integrate literary knowledge of genres and periods from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, demonstrating how literature is a manifestation of culture and how literary form functions to enable this artistic expression. -

Copyright by Peter David Siegenthaler 2004

Copyright by Peter David Siegenthaler 2004 The Dissertation Committee for Peter David Siegenthaler certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Looking to the Past, Looking to the Future: The Localization of Japanese Historic Preservation, 1950–1975 Committee: Susan Napier, Supervisor Jordan Sand Patricia Maclachlan John Traphagan Christopher Long Looking to the Past, Looking to the Future: The Localization of Japanese Historic Preservation, 1950–1975 by Peter David Siegenthaler, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2004 Dedication To Karin, who was always there when it mattered most, and to Katherine and Alexander, why it all mattered in the first place Acknowledgements I have accumulated many more debts in the course of this project than I can begin to settle here; I can only hope that a gift of recognition will convey some of my gratitude for all the help I have received. I would like to thank primarily the members of my committee, Susan Napier, Patricia Maclachlan, Jordan Sand, Chris Long, and John Traphagan, who stayed with me through all the twists and turns of the project. Their significant scholarly contributions aside, I owe each of them a debt for his or her patience alone. Friends and contacts in Japan, Austin, and elsewhere gave guidance and assistance, both tangible and spiritual, as I sought to think about approaches broader than the immediate issues of the work, to make connections at various sites, and to locate materials for the research. -

A Tanizaki Feast

A Tanizaki Feast Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies Number 24 Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan A Tanizaki Feast The International Symposium in Venice Edited by Adriana Boscaro and Anthony Hood Chambers Center for Japanese Studies The University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1998 Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. 1998 The Regents of the University of Michigan Published by the Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan, 202 S. Thayer St., Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1608 Distributed by The University of Michigan Press, 839 Greene St. / P.O. Box 1104, Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1104 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data A Tanizaki feast: the international symposium in venice / edited by Adriana Boscaro and Anthony Hood Chambers. xi, 191 p. 23.5 cm. — (Michigan monograph series in Japanese studies ; no. 24) Includes index. ISBN 0-939512-90-4 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Tanizaki, Jun'ichir5, 1886—1965—Criticism and interpreta- tion—Congress. I. Boscaro, Adriana. II. Chambers, Anthony H. (Anthony Hood). III. Series. PL839.A7Z7964 1998 895.6'344—dc21 98-39890 CIP Jacket design: Seiko Semones This publication meets the ANSI/NISO Standards for Permanence of Paper for Publications and Documents in Libraries and Archives (Z39.48-1992). Published in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-939512-90-4 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-472-03838-1 (paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12816-7 (ebook) ISBN 978-0-472-90216-3 (open access) The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Contents Preface vii The Colors of Shadows 1 Maria Teresa Orsi The West as Other 15 Paul McCarthy Prefacing "Sorrows of a Heretic" 21 Ken K. -

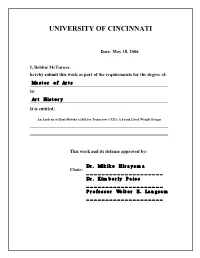

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 18, 2006 I, Bobbie McTurner, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: An Analysis of Hani Motoko’s Hall for Tomorrow (1921): A Frank Lloyd Wright Design This work and its defense approved by: Dr. Mikiko Hirayama Chair: ____________________ Dr. Kimberly Paice ____________________ Professor Walter E. Langsam ____________________ UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI COLLEGE OF DESIGN, ARCHITECTURE, ART, AND PLANNING An Analysis of Hani Motoko’s Hall for Tomorrow (1921): A Frank Lloyd Wright Design A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE ART HISTORY FACULTY IN CANDIDANCY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ART HISTORY by BOBBIE MCTURNER 2006 B.A., University of Cincinnati, 2001 Committee Chairs: Mikiko Hirayama, Ph.D., & Kimberly Paice, Ph.D. Committee Reader: Adjunct Associate Professor Walter E. Langsam ABSTRACT There is a plethora of publications concerning Frank Lloyd Wright’s (1867-1959) works, I investigate a design that has received little attention from American historians. In 1921 Wright was commissioned by Hani Motoko (1873-1957) and her spouse Hani Yoshikazu (1880- 1955) to create a school building. The result was Myōnichikan. This structure is worthy of discussion, not only because it is one of only three remaining Wright designs in Japan, but also because Hani Motoko is an important figure whose accomplishments deserve consideration. In this study I include a brief look at the basis of Wright’s educational philosophies. An institutional analysis of Japan’s educational system is also integral because it illustrates the Japanese government’s goals for education, specifically those for young women, and also allows for a later comparison of the Hanis’ educational objectives. -

The SCBWI Tokyo Newsletter Contents from the Editors

The SCBWI Tokyo Newsletter Winter 2011 Carp Tales is the bi-annual newsletter of the Tokyo chapter of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI). The newsletter includes SCBWI Tokyo chapter and member news, upcoming events, a bulletin board of announcements related to writing and illustrating for children in Japan, reports of past events, information on industry trends, interviews with authors and illustrators, and other articles related to children’s literature. To submit inquiries or learn how to contribute to Carp Tales, contact [email protected]. The submission deadline is May 1 for the spring issue and November 1 for the fall issue. All articles and illustrations in Carp Tales are © SCBWI Tokyo and the contributing writers and illustrators. For more information about SCBWI Tokyo, see www.scbwi.jp. The Carp Tales logo is © Naomi Kojima. From the Editors Contents The Year of the Rabbit has begun, bringing with it the SCBWI Winter From the Editors ................................1 Conference in New York and the opening SCBWI Tokyo event, Frané SCBWI Tokyo Event Wrap-Ups ..........2 Lessac’s presentation on “Writing Global Picture Books.” An Interview with Naomi Kojima, The Year of the Tiger was full of spirit, and the second half kept Translator of Dear Genius: everyone busy: midsummer brought Jed Henry’s workshop on using The Letters of Ursula Nordstrom ........4 Adobe Photoshop; autumn brought a creative exchange, presentations at the Japan Writers Conference, and a visit from children’s literature Heart of a Samurai Named scholar Leonard Marcus. (Dear Genius: The Letters of Ursula Newbery Honor Book .........................8 Nordstrom, edited by Marcus, was recently translated into Japanese by SCBWI Tokyo Japan Liaison Naomi Kojima. -

The Aesthetics of Distance and Jun'ichiro Tanizaki by Yasuko Kanayama B.A., Tokyo Women's Christian University, Tokyo, 1986 a Th

The Aesthetics of Distance and Jun'ichiro Tanizaki by Yasuko Kanayama B.A., Tokyo Women's Christian University, Tokyo, 1986 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for degree of Master of Arts in The Faculty of Graduate Studies Department of Asian Studies We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard The University of British Columbia April 1997 ©Yasuko Kanayama, 1997 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date jfaAjtf. (6 , DE-6 (2/88) 11 Abstract The aim of this thesis is to examine the transformation and development of Jun'ichiro Tanizaki's "Aesthetics of distance" in male-female relationship as well as in the main characters' perception of reality, through his three major works: Chijin no ai (Naomi), Shunkinsho (The Story of Shunkin), and Fulen rojin nikki (A Diary of a Mad Old Man). For Tanizaki, distance, whether in a spiritual, spatial, or social dimension, functions as a mechanism through which characters and readers perceive as well as measure reality. Furthermore, for him, beauty is measured by remoteness (distance) from man's existence. -

Special Article 2

Special Article 2 By Mukesh WILLIAMS Author Mukesh Williams No matter what complaints we may have, Japan has chosen to follow the West, and there is nothing for her to do but move bravely ahead and leave us old ones behind. But we must be resigned to the fact that as long as our skin is the color it is the loss we have suffered cannot be remedied. – Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows (1933) The heart of mine is only one, it cannot be known by anybody but myself. – Tanizaki, tanka (1963) PHOTO 1 Photo: Mainichi Newspaper/AFLO TheLet's thoughts and Learn writings of Junichiro a Lesson from How Kaoruand the devious schemes of a sexually Tanizaki (1886-1965)(Photo 1) reflect an hyperactive professor in The Key to force Ishikawainteresting mixture of the modernEstablished (kindai) KAIZEN (Japanesean adulterous QC) relationship. between his wife and classical (koten kaiki) with ever-changing and a family friend to heighten his own themes to cater to a demanding audience. He voyeuristic pleasure. was not interested in eulogizing the past but Through these stories Tanizaki heralds in understanding how the present was the destruction of traditional Japanese shaped by it. He extolled the virtues of aesthetics, the rise of the nuclear Japanese Japanese history, culture and aesthetics but family and the proliferation of Western also felt the pressure from rampant modernity in Japan where traditional urbanization, industrial capitalism and standards do not work. He is both Marxist ideology. Often an essentialist in Ambassador’s Viewfascinated and troubled by urban thought, he wanted Japan to remain consumerism, Marxist thought, unchanged but realized that an unstoppable TPP: cinematography and contemporary social change had already set in. -

The Female Figures in Aesthetic Literature in Early Twentieth-Century China and Japan—Yu Dafu and Tanizaki Junichiro As Examples

The Female Figures in Aesthetic Literature in Early Twentieth-Century China and Japan—Yu Dafu and Tanizaki Junichiro as Examples by Ruoyi Bian Critical Asian Humanities Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Carlos Rojas, Advisor ___________________________ Leo Ching ___________________________ Negar Mottahedeh Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Critical Asian Humanities in the Graduate School of Duke University 2020 i v ABSTRACT The Female Figures in Aesthetic Literature in Early Twentieth-Century China and Japan—Yu Dafu and Tanizaki Junichiro as Examples by Ruoyi Bian Critical Asian Humanities Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Carlos Rojas, Advisor ___________________________ Leo Ching ___________________________ Negar Mottahedeh An abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Critical Asian Humanities in the Graduate School of Duke University 2020 Copyright by Ruoyi Bian 2020 Abstract In this thesis, I mainly discussed the commonalities and differences between two representative authors of Chinese and Japanese aesthetic literature in the early 20th century: Yu Dafu and Tanizaki Junichiro, in terms of the female figures, from the perspective of feminism and interrelations between different genders. Also, I tried to look into the possible reasons for these similarities and differences and how we could understand them within the socio-historical background of East Asia in a shifting period. To achieve a deeper and more comprehensive discussion, I took the combined methods of socio-historical discussion and textual analysis in my thesis. The three chapters were based on the analysis and reference of historical materials, data, journals, original and translated literary texts, and academic research papers. -

Tanizaki Jun'ichirō's Modern Girls

Tanizaki Jun’ichirō’s Modern Girls: Reversing the Role of Moga in Japanese Literature Aslı İdil Kaynar Boğaziçi University, Asian Studies Center, MAAS Abstract This research explores moga’s (Japanese modern girl) representations in Tanizaki Jun’ichirō’s (1886-1965) literary texts. Examining moga’s posi- tion within Tanizaki’s writings, the study supports the idea that although moga was portrayed negatively by the Japanese media Tanizaki’s descrip- tions of moga can be approached differently. In the 1920s and 1930s moga drew attention due to her Westernized looks and the way she took an active part in the public space. For these reasons, she became an inspi- ration for many authors. This paper presents an overview of Tanizaki’s portrayal of modern girls. It looks into modes of objectification and types of women in Tanizaki’s earlier novels and short stories. This study sur- veys the following works: The Tattooer(Shisei, 1910), Kirin (1910), Professor Rado (1928) and Naomi (Chijin no ai, 1925). Through context-based anal- ysis of Tanizaki Jun’ichirō’s selected literary works this study reveals the common patterns in the protagonists’ relationships with the modern girl analyzed within the theoretical framework of objectification, drawing on Martha Nussbaum’s idea of positive objectification and Sandra Lee Bart- ky’s concept of narcissism and the male gaze. Tanizaki introduces various types of the modern girl in his early novels and short stories, thus this research argues that moga in real life was a complex figure that cannot be simply categorized as a product of mass culture. Keywords: Japanese modern literature, the modern girl, representa- tions of women in literature, gender, literature and media, objectification. -

HRS 174: Japanese Culture and Literature Spring 2016; Tuesdays 6:00-8:50; Mariposa Hall 1001

HRS 174: Japanese Culture and Literature Spring 2016; Tuesdays 6:00-8:50; Mariposa Hall 1001 General Information Prof. Jeffrey Dym Office: Tahoe 3088 e-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Wednesday 10:00-12:00, Thursday 11:00-12:00, & by appointment Catalog Description HRS 174. Modern Japanese Literature & Culture. The study of representative Japanese literature of the late Tokugawa period and of modern Japan through English translations. GE area C-2 Course Description This course is designed to be a survey of modern Japanese culture and literature. We will be reading seven works in translation as well as viewing seven feature films that represent a broad cross-section of some of the finest works produced in Japan during the twentieth century. The aim of this course is not only to introduce students to Japanese literature and cinema but also to use these mediums as a window into Japanese culture and sensibilities. Much of the class will revolve around in-class discussions of the works read and viewed. These discussions will be supplemented by lectures on Japanese culture. Through a combination of lectures, readings, and films each student will gain a fundamental understanding of modern Japanese culture. Moreover, the assignments are designed to encourage analytical thinking and intellectual growth. Course Learning Objectives Students completing this course should be able to: 1. Demonstrate knowledge of the conventions and methods of the study of the humanities. 2. Investigate, describe, and analyze the roles and effects of human culture and understanding in the development of human societies. 3. Compare and analyze various conceptions of humankind. -

JAPANESE CULTURAL WESTERNIZATION in the 1920S AS REFLECTED THROUGH the MAIN CHARACTERS in JUNICHIRO TANIZAKI’S NAOMI

JAPANESE CULTURAL WESTERNIZATION IN THE 1920s AS REFLECTED THROUGH THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN JUNICHIRO TANIZAKI’S NAOMI AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By FRANCISCA NUGRAHENI ROSARI WULAN Student Number: 064214056 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2010 JAPANESE CULTURAL WESTERNIZATION IN THE 1920s AS REFLECTED THROUGH THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN JUNICHIRO TANIZAKI’S NAOMI AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By FRANCISCA NUGRAHENI ROSARI WULAN Student Number: 064214056 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2010 i “Success is not measured by what you accomplish, but by the opposition you have encountered, and the courage with which you have maintained the struggle against overwhelming odds.” (Orison Swett Marden ) iv This Undergraduate Thesis is dedicated to: Jesus Christ and Mother Mary My Beloved Parents, Fx. Rustamanto & My. Sri Utami My sister, Maria Ika Widiyawati My brother, Timotius Dudik My brother, Andreas Novianto Heru Utomo My nephews and nieces: Marcell, Monic, Ave, Samuel My beloved boyfriend, Dian Saputra v ACKNOWLEDMENTS First of all I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Jesus Christ and mother Mary. Without all the guidance, opportunities and blessings, I will not be able to finish my thesis. Secondly, I want to thank my advisor Ni Luh Putu Rosiandani, S.S, M. Hum and my co-advisor Drs. Hirmawan Wijanarka, M. Hum, for all their advise and guidance.