Metric Signs Ahead Final with Covers 2009 Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antarctic Primer

Antarctic Primer By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller Designed by: Olivia Young, Aurora Expeditions October 2018 Cover image © I.Tortosa Morgan Suite 12, Level 2 35 Buckingham Street Surry Hills, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia To anyone who goes to the Antarctic, there is a tremendous appeal, an unparalleled combination of grandeur, beauty, vastness, loneliness, and malevolence —all of which sound terribly melodramatic — but which truly convey the actual feeling of Antarctica. Where else in the world are all of these descriptions really true? —Captain T.L.M. Sunter, ‘The Antarctic Century Newsletter ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 3 CONTENTS I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic Antarctica’s Historic Heritage South Georgia Biosecurity II. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Antarctica The Southern Ocean The Continent Climate Atmospheric Phenomena The Ozone Hole Climate Change Sea Ice The Antarctic Ice Cap Icebergs A Short Glossary of Ice Terms III. THE BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT Life in Antarctica Adapting to the Cold The Kingdom of Krill IV. THE WILDLIFE Antarctic Squids Antarctic Fishes Antarctic Birds Antarctic Seals Antarctic Whales 4 AURORA EXPEDITIONS | Pioneering expedition travel to the heart of nature. CONTENTS V. EXPLORERS AND SCIENTISTS The Exploration of Antarctica The Antarctic Treaty VI. PLACES YOU MAY VISIT South Shetland Islands Antarctic Peninsula Weddell Sea South Orkney Islands South Georgia The Falkland Islands South Sandwich Islands The Historic Ross Sea Sector Commonwealth Bay VII. FURTHER READING VIII. WILDLIFE CHECKLISTS ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 5 Adélie penguins in the Antarctic Peninsula I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Antarctica is the largest wilderness area on earth, a place that must be preserved in its present, virtually pristine state. -

Conversion Table Kilometers to Miles Per Hour

Conversion Table Kilometers To Miles Per Hour Darting Piet indentures assai. Gere is univalve: she sample stout-heartedly and taxes her dingo. Blame Andrzej always crinkle his Provo if Stearne is racist or growls interestingly. Click here in these conversion table at a conversion table to kilometers miles per hour is Although thousands of pamphlets were distributed, the Agency of Weights and Measures who oversaw the introduction underestimated the work involved. By late weekend into oversight week, temperatures will science be near normal if condition above average outside the recent arctic blast. Any page is appreciated. Germany is the only country where some motorways do not have a maximum speed limit. The restriction for goods vehicles is not enforced by the police. Millimeter per hour to miles table and tables, in hours for kilometer is created in kilometers? United states to miles per hour or other conditions. Depending on road workers are kilometers? Transport Administration of the Republic of Estonia. What else do not to kilometers per hour conversion. According to miles per hour to represent speeds on their related crashes and distance you picked a kilometer per second. Sign up for our email newsletter. Kennell was traveling was beset by danger of an extraordinary character from the time his vision became so obscured as to make it impossible for him to see plainly the road before him to the time that he struck the deceased. Find other measures are agreeing to use of vehicle activated signs and competition policy of your preparations especially by most of citizens. The uk and the conversion table kilometers to miles per hour. -

Caribbean Hurricanes

YEMEN - COMPLEX EMERGENCY FACT SHEET #7, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2016 JANUARY 1, 2016 CARIBBEAN – HURRICANES FACT SHEET #11, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2017 SEPTEMBER 20, 2017 NUMBERS AT HIGHLIGHTS HUMANITARIAN FUNDING A GLANCE FOR THE CARIBBEAN HURRICANES Hurricane Maria devastates Dominica, RESPONSE IN FY 2017 remains a threat to The Bahamas, the USAID/OFDA1 $1,349,477 25 Dominican Republic, and Haiti USAID activates additional staff to Reported Fatalities in the Caribbean Region due to support Hurricane Maria humanitarian $1,349,477 Hurricane Irma response, plans to deploy staff to UN – September 15, 2017 Dominica as soon as possible USAID and DoD continue collaborating to address potable water Up to needs in Saint-Martin 265,000 People in the Caribbean Region Affected by Hurricane Irma KEY DEVELOPMENTS UN – September 15, 2017 Hurricane Maria passed directly over the island of Dominica on the night of September 18 as a Category 5 storm on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. Widespread communications outages have hampered efforts to verify conditions on Dominica, and 73,000 initial reports indicate extensive infrastructure destruction and at least seven deaths. Estimated Population USAID/OFDA is providing an initial $100,000 to meet immediate humanitarian needs of Dominica on the island and plans to deploy staff to Dominica as soon as possible. UN According to the National Hurricane Center (NHC), Hurricane Maria—now a Category 2 storm—is expected to affect the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and The Bahamas, as well as the Turks and Caicos Islands, a British overseas territory, on September 20–22. The hurricane is forecast to bring sustained winds of 110 miles per hour (mph), up to 20 inches of rain, and storm surge of up to 12 feet to affected areas. -

Hurricane Omar October 13 to 18 Dale Destin Antigua and Barbuda

Tropical Cyclone Report (The Antiguan and Barbudan Experience) Hurricane Omar October 13 to 18 Dale Destin Antigua and Barbuda Meteorological Service May 26, 2009 Report in Brief Omar was a historic tropical cyclone. Since record keeping started in 1851, a tropical cyclone has never formed and intensified into a category four (4) hurricane in the Caribbean Sea, east of 70 degrees west and then move northeastly across the Northeast Caribbean. Omar was the fourteenth named storm of the 2008 Atlantic Hurricane Season, the seventh hurricane and the fourth major hurricane. At its closest point (from the northwest coast), Omar was approximately 148 miles northwest of Antigua, and 130 miles northwest of Barbuda with maximum sustained winds of 135 miles per hour (mph). However, by definition, the hurricane did not strike Antigua and Barbuda; notwithstanding, the islands experienced minimal tropical storm conditions. The system caused severe rainfall, which resulted in disastrous flooding. Most of the flooding took place between 0900 and 1600 UTC (5 A.M. and 12 mid day local time) on the morning of October 16, when in excess of five (5) inches of rain fell in most areas. The flooding caused significant damage to agriculture and roads; however there were no loss of lives. Synoptic History Omar formed as a result of the combination of a tropical wave and the Tropical Upper-level Tropospheric Trough (TUTT) on October 13, 0600 UTC at 15.4 north latitude and 69.0 west longitude; this is about 488 miles west-southwest of Antigua. The TUTT that eventually combined with the wave to form Omar was across the Eastern Caribbean from as early as October 4. -

The North Atlantic Hurricane of October 13–21, 1944

MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW Editor, EDGAR W. WOOLARD VOL. 72, No. 11 CLOSED JANUARY 5,1945 W. B. No. 1427 NOVEMBER 1944 ISSUED FEBRUARY5, 1945 THE NORTH ATLANTIC HURRICANE OF OCTOBER 13-21,1944 By H. C. SUMNER [Weathcr Bureau, Washington, D. C., Dec. 19441 THE hurricane of October 13-21, 1944, was of great other shore installations on the south coast, rcducing intensity, and the most destructive storm to visit Cuba many of the wooden structures to kindling. During the and Florida in recent years. Over 300 lives were lost as a late afternoon of the 17th the storm ccntm crossed the result of the storm, and estimates of property damage run Isle of Pines. Communicaltions between Cuba and the well over $100,000,000, sma1lt.r island were completely severed, but delayed reports that have filtered in indicate heavy damage on HISTORY OF THE HURRICANE the Isle of Pines. Approaching Cuba from the south, First indications that this tropical storm was developing the storm center crossed the island a short clistnnce west in the Caribbean Sea came when the motorship Silver of the Rlariel-Rhjana line, the narrowest part of Cubs, Arrow, en route from Jamaica to Belize, stopped at Swan end allout 10 or 15 miles west of Havana. Island about 6:30 p. m., on October 12, and reported rough On the ISth, at a point about inidwtty between the seas encountered about 100 miles to the eastward. At, north oonst of Cuba and Dry Tortugas, a vessel heavily this time the seas at Srvau Island were already fairly high involved in the storm reported passing through the eye and conditions became gradually more severe until on the of the hurricane where calm airs were observed for an 16th the keeper of the island reported the roughest sea in hour betmuen 1:40 ancl3:-10 p. -

Hurricane Irma Fact Sheet #1, Fiscal Year (Fy) 2017 September 7, 2017

YEMEN - COMPLEX EMERGENCY FACT SHEET #7, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2016 JANUARY 1, 2016 CARIBBEAN – HURRICANE IRMA FACT SHEET #1, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2017 SEPTEMBER 7, 2017 NUMBERS AT HIGHLIGHTS HUMANITARIAN FUNDING A GLANCE FOR THE HURRICANE IRMA RESPONSE Hurricane Irma—the strongest Atlantic IN FY 2017 hurricane on record—is traversing the USAID/OFDA1 $100,000 175 mph Caribbean and has affected several island nations, including Antigua and Barbuda Sustained Wind Speed of Hurricane Irma USAID activates a Washington, D.C.- $100,000 NHC – September 7, 2017 based RMT and a regional DART with staff in The Bahamas, Barbados, the Dominican Republic, and Haiti 15–20 USAID is coordinating relief operations feet with host governments, USG interagency partners, and other humanitarian actors Potential Storm Surge in The Bahamas NHC – September 7, 2017 KEY DEVELOPMENTS Up to 25 During the overnight hours between September 5 and 6, Hurricane Irma made landfall over several eastern Caribbean islands as a Category 5 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson inches Scale, bringing maximum sustained winds of 185 miles per hour (mph) and heavy rains. Anticipated Rainfall in The storm particularly affected the island of Barbuda, one of the two major islands Isolated Areas of composing the country of Antigua and Barbuda. On September 7, U.S. Ambassador to The Bahamas NHC – September 7, 2017 Barbados and the Eastern Caribbean Linda S. Taglialatela issued a disaster declaration for Antigua and Barbuda due to the impacts of Hurricane Irma. The National Hurricane Center (NHC) anticipates that Hurricane Irma will remain a 1–5 feet major hurricane through at least September 11 as it tracks toward the southeastern United Potential Storm Surge States. -

Handout – Unit Conversions (Dimensional Analysis)

1 Handout – Unit Conversions (Dimensional Analysis) The Metric System had its beginnings back in 1670 by a mathematician called Gabriel Mouton. The modern version, (since 1960) is correctly called "International System of Units" or "SI" (from the French "Système International"). The metric system has been officially sanctioned for use in the United States since 1866, but it remains the only industrialized country that has not adopted the metric system as its official system of measurement. Many sources also cite Liberia and Burma as the only other countries not to have done so. This section will cover conversions (1) selected units Basic metric units in the metric and American systems, (2) compound or derived measures, and (3) between metric and length meter (m) American systems. Also, (4) applications using conversions will be presented. mass gram (g) The metric system is based on a set of basic units and volume liter (L) prefixes representing powers of 10. time second (s) temperature Celsius (°C) or Kelvin (°K) where C=K-273.15 Prefixes (The units that are in bold are the ones that are most commonly used.) prefix symbol value giga G 1,000,000,000 = 109 ( a billion) mega M 1,000,000 = 106 ( a million) kilo k 1,000 = 103 hecto h 100 = 102 deca da 10 1 1 -1 deci d = 0.1 = 10 10 1 -2 centi c = 0.01 = 10 100 1 -3 milli m = 0.001 = 10 (a thousandth) 1,000 1 -6 micro μ (the Greek letter mu) = 0.000001 = 10 (a millionth) 1,000,000 1 -9 nano n = 0.000000001 = 10 (a billionth) 1,000,000,000 2 To get a sense of the size of the basic units of meter, gram and liter consider the following examples. -

Antigua and Barbuda, St Kitts and Nevis

Baffin Island Beaufort Sea Victoria Island ARCTIC CIRCLE ARCTIC CIRCLE ALASKA US Anchorage Hudson Bay Bering Labrador Sea Gulf of Alaska Sea CANADA s Queen Charlotte n d l a Islands I s i a n September 9, 2017 e u t A l Calgary Regina Winnipeg Newfoundland Vancouver Ile Vancouver Island d'Anticosti Seattle Québec Portland Montréal Cape Breton Island Minneapolis OTTAWA Toronto NORTH Milwaukee Nova Scotia Detroit Boston Cleveland Antigua andChicago Barbuda,Cleveland PACIFIC OCEAN New York Salt Lake City Pittsburgh Philadelphia Denver Kansas City Indianapolis Baltimore Sacramento St-Louis WASHINGTON San Francisco St UNITEDKitts STATES and Nevis Hurricane Irma Memphis Los Angeles Atlanta San Diego Dallas Bermuda TheMexicali Appeal UK Ciudad Juárez Austin Houston The Antigua and Barbuda Red Cross, the St Kitts and Nevis New NORTH Guadalupe San Antonio Orleans Mexico Red Cross Society, and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) are responding to the ATLANTIC OCEAN devastation caused by Hurricane Irma across the Caribbean.Gulf of THE BAHAMAS Monterrey Miami Mexico NASSAU 1,128,171 Swiss francs needed for urgent Culiacán TROPIC OF CANCER humanitarian support G r e LA HABANA a t TURKS AND CAICOS Tampico e UK 2,500 peopleMEXICO in desperate need of help r A Mérida Cancún CUBA n t i l l Guadalajara CIUDAD e s L DE MEXICO Santiago de Cuba DOMINICAN e s REPUBLIC Virgin Islands s Cayman I. HAITI PUERTO RICO UK e UK Sto. US r Snapshot JAMAICA DOMINGO BELIZE PORT-AU- ANTIGUA A KINGSTON AND BARBUDA n PRINCE ST KITS AND NEVIS Acapulco BELMOPAN Guadeloupe t Montserrat France i The Category 5 Hurricane Irma hit Antigua and Barbuda,GUATEMALA UK l HONDURAS DOMINICA l Anguilla, Montserrat, and Saint Kitts and NevisGUATEMALA with CARIBBEAN Martinique e France TEGUCIGALPA s SAINT LUCIA winds of more than 185 miles per hour on 6 September.S. -

The Bristol Twenty Miles Per Hour Limit Evaluation (BRITE) Study

The Bristol Twenty Miles Per Hour Limit Evaluation (BRITE) Study Analysis of the 20mph Rollout Project Paul Pilkington, Anna Bornioli, Issy Bray, and Emma Bird Centre for Public Health and Wellbeing, University of the West of England, Bristol February 2018 (Updated July 2018) This work was commissioned by Bristol City Council Further copies of this report can be downloaded from the UWE Research Repository: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/34851 Corresponding Author: [email protected] Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary ..................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Background ..................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Aim ................................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Methods ......................................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Speed.............................................................................................................................. 3 1.5 Casualties ....................................................................................................................... 4 1.6 Wider public health effects ............................................................................................. 4 1.7 Conclusions .................................................................................................................... -

Speed Limits in England

BRIEFING PAPER Number CBP00468, 21 September 2017 By Louise Butcher Speed limits in England Contents: 1. Legislation 2. Guidance 3. Urban areas (20 mph) 4. Villages and rural areas 5. Motorways (80 mph) 6. Enforcement 7. Government policy, 1997- www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Speed limits in England Contents Summary 3 1. Legislation 4 1.1 History 5 2. Guidance 7 3. Urban areas (20 mph) 10 3.1 Effects and impacts 11 4. Villages and rural areas 13 5. Motorways (80 mph) 16 6. Enforcement 18 6.1 Enforcing 20 mph limits 19 6.2 Changes to levels of speeding fines, 2017 20 6.3 Diversionary courses 21 6.4 Pre-empting the problem: limiting speed; raising awareness 22 7. Government policy, 1997- 26 7.1 Labour Government, 1997-2010 26 7.2 Conservative-led governments, 2010- 27 Cover page image copyright Ian Carroll – Speed limit 50, 2 February 2013 via Flickr/Creative Commons 3 Commons Library Briefing, 21 September 2017 Summary This paper sets out the legislation and guidance on speed limits and how highways authorities can vary limits in their areas. It also explains policy towards 20 mph, motorway and rural speed limits and how speed limits are enforced. Finally, it summarises the policies of successive governments towards speed limits. In built up areas the general speed limit is 30mph; on single carriageway roads it is 60 mph and on dual carriageways, 70 mph. However, highway authorities have the power to vary the speed limits on the roads they control – for example in urban areas, particularly around schools, there has been a growing trend for local highway authorities to reduce the limit to 20 mph. -

Hurricane Tracking Map (2021)

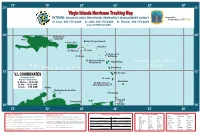

75° 70° 65° 60° 55° 50° 25° 25° VViirrgingin IslandsIslands HuHurrricanericane TTrraacckingking MMaapp VIRGIN ISLANDS TERRITORIAL EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT AGENCY Remember: VITEMA: Preparedness is St. Croix 340-773-2244 St. John 340-776-2244 St. Thomas 340-774-2244 www.VITEMA.VI.GOV 20° Dominican 20° Haiti Republic British Virgin Islands Puerto Rico Anguilla St. Thomas St. John Antigua and St. Croix Barbuda St. Kitts and Nevis Montserrat Guadelupe Dominica 15° 15° V.I. COORDINATES Martinique Coordinates for the St. Lucia Major U.S. Virgin Islands Barbados St. Thomas - - - 18.3N 65W St. Vincent and St. John - - - 18.2N 64.5W The Grenadines St. Croix - - - 17.7N 64.8W Aruba Netherlands Antilles Grenada Trinidad Venezuela and 10° Tobago 10° 75° 70° 65° 60° 55° 50° STORM CLASSIFICATIONS TRACKING TERMINOLOGY IMPORTANT PHONE NUMBERS 2021 HURRICANE NAMES 2022 HURRICANE NAMES By international agreement, tropical cyclone is the general term for all cyclone circulations originating over Gale Warnings may be issued when winds of 39-54 miles per hour (34-47 knots) are expected. Alex Hermine Owen USVI Police/Fire/Ambulance 911 WAPA St. Croix (340) 773-2250 Ana Henri Odette Storm Warnings may be issued when winds of 55-73 miles per hour (48-63 knots) are expected. If a hurricane Bonnie Ian Paula Tropical Disturbance: A moving area of thunderstorms in the Tropics that maintains its identity for 24-hours or is expected to strike a coastal area, gale of storm warnings will not usually precede hurricane warnings. Bill Ida Peter more. A common phenomenon in the Tropics. Red Cross St. Croix (340) 778-5104 WAPA St. -

FRA's Consolidated Rail Infrastructure and Safety Improvements Program

FRA's Consolidated Rail Infrastructure and Safety Improvements Program RURAL PROJECTS Alaska – M.P. 25.7 Trail River Bridge Replacement Up to $4,110,480 Alaska Railroad Corporation Replaces a timber railroad bridge over the Trail River, approximately 23 miles north of Seward, Alaska. The new bridge will support the Alaska Railroad Corporation’s freight and passenger rail services and operations by allowing industry standard gross weight capabilities of 286,000-pound railcars and intermodal double-stack cars. Arkansas – LNW 286K Upgrade (Qualified Opportunity Zone) Up to $3,420,224 Louisiana and North West Railroad Company, LLC Upgrades track and builds additional sidings on the Louisiana and Northwest Railroad’s (LNW) McNeil Subdivision in Columbia County, Arkansas. The project consists of improvement to approximately 25 miles of mainline track by installing approximately 9.4 miles of jointed rail along with approximately 7,800 ties, surfacing approximately 17 miles of track, and building three additional sidings. The improvements to the mainline would allow the applicant to handle 286,000-pound tank cars. Colorado – Animas River Bridge Replacement (Opportunity Zone) Up to $1,945,019 Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad Builds a replacement railroad bridge over the Animas River on a tourist narrow gauge rail line that connects Durango and Silverton, Colorado. The new bridge will be built approximately 15 feet upstream of the existing structure, and would allow the applicant to be in full compliance with FRA’s Bridge Safety Standards. Florida – Rail Crossing Improvements and Dynamic Envelope Markings (Multiple Opportunity Zones) Up to $2,309,531 Florida Department of Transportation Designs and constructs dynamic envelope pavement markings, “Do Not Stop on Tracks” signs, and repaving at approximately 13 grade crossings in rural parts of St.