Harmony and Figured Bass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Naming a Chord Once You Know the Common Names of the Intervals, the Naming of Chords Is a Little Less Daunting

Naming a Chord Once you know the common names of the intervals, the naming of chords is a little less daunting. Still, there are a few conventions and short-hand terms that many musicians use, that may be confusing at times. A few terms are used throughout the maze of chord names, and it is good to know what they refer to: Major / Minor – a “minor” note is one half step below the “major.” When naming intervals, all but the “perfect” intervals (1,4, 5, 8) are either major or minor. Generally if neither word is used, major is assumed, unless the situation is obvious. However, when used in naming extended chords, the word “minor” usually is reserved to indicate that the third of the triad is flatted. The word “major” is reserved to designate the major seventh interval as opposed to the minor or dominant seventh. It is assumed that the third is major, unless the word “minor” is said, right after the letter name of the chord. Similarly, in a seventh chord, the seventh interval is assumed to be a minor seventh (aka “dominant seventh), unless the word “major” comes right before the word “seventh.” Thus a common “C7” would mean a C major triad with a dominant seventh (CEGBb) While a “Cmaj7” (or CM7) would mean a C major triad with the major seventh interval added (CEGB), And a “Cmin7” (or Cm7) would mean a C minor triad with a dominant seventh interval added (CEbGBb) The dissonant “Cm(M7)” – “C minor major seventh” is fairly uncommon outside of modern jazz: it would mean a C minor triad with the major seventh interval added (CEbGB) Suspended – To suspend a note would mean to raise it up a half step. -

MTO 0.7: Alphonce, Dissonance and Schumann's Reckless Counterpoint

Volume 0, Number 7, March 1994 Copyright © 1994 Society for Music Theory Bo H. Alphonce KEYWORDS: Schumann, piano music, counterpoint, dissonance, rhythmic shift ABSTRACT: Work in progress about linearity in early romantic music. The essay discusses non-traditional dissonance treatment in some contrapuntal passages from Schumann’s Kreisleriana, opus 16, and his Grande Sonate F minor, opus 14, in particular some that involve a wedge-shaped linear motion or a rhythmic shift of one line relative to the harmonic progression. [1] The present paper is the first result of a planned project on linearity and other features of person- and period-style in early romantic music.(1) It is limited to Schumann's piano music from the eighteen-thirties and refers to score excerpts drawn exclusively from opus 14 and 16, the Grande Sonate in F minor and the Kreisleriana—the Finale of the former and the first two pieces of the latter. It deals with dissonance in foreground terms only and without reference to expressive connotations. Also, Eusebius, Florestan, E.T.A. Hoffmann, and Herr Kapellmeister Kreisler are kept gently off stage. [2] Schumann favours friction dissonances, especially the minor ninth and the major seventh, and he likes them raw: with little preparation and scant resolution. The sforzato clash of C and D in measures 131 and 261 of the Finale of the G minor Sonata, opus 22, offers a brilliant example, a peculiarly compressed dominant arrival just before the return of the main theme in G minor. The minor ninth often occurs exposed at the beginning of a phrase as in the second piece of the Davidsbuendler, opus 6: the opening chord is a V with an appoggiatura 6; as 6 goes to 5, the minor ninth enters together with the fundamental in, respectively, high and low peak registers. -

A Group-Theoretical Classification of Three-Tone and Four-Tone Harmonic Chords3

A GROUP-THEORETICAL CLASSIFICATION OF THREE-TONE AND FOUR-TONE HARMONIC CHORDS JASON K.C. POLAK Abstract. We classify three-tone and four-tone chords based on subgroups of the symmetric group acting on chords contained within a twelve-tone scale. The actions are inversion, major- minor duality, and augmented-diminished duality. These actions correspond to elements of symmetric groups, and also correspond directly to intuitive concepts in the harmony theory of music. We produce a graph of how these actions relate different seventh chords that suggests a concept of distance in the theory of harmony. Contents 1. Introduction 1 Acknowledgements 2 2. Three-tone harmonic chords 2 3. Four-tone harmonic chords 4 4. The chord graph 6 References 8 References 8 1. Introduction Early on in music theory we learn of the harmonic triads: major, minor, augmented, and diminished. Later on we find out about four-note chords such as seventh chords. We wish to describe a classification of these types of chords using the action of the finite symmetric groups. We represent notes by a number in the set Z/12 = {0, 1, 2,..., 10, 11}. Under this scheme, for example, 0 represents C, 1 represents C♯, 2 represents D, and so on. We consider only pitch classes modulo the octave. arXiv:2007.03134v1 [math.GR] 6 Jul 2020 We describe the sounding of simultaneous notes by an ordered increasing list of integers in Z/12 surrounded by parentheses. For example, a major second interval M2 would be repre- sented by (0, 2), and a major chord would be represented by (0, 4, 7). -

Many of Us Are Familiar with Popular Major Chord Progressions Like I–IV–V–I

Many of us are familiar with popular major chord progressions like I–IV–V–I. Now it’s time to delve into the exciting world of minor chords. Minor scales give flavor and emotion to a song, adding a level of musical depth that can make a mediocre song moving and distinct from others. Because so many of our favorite songs are in major keys, those that are in minor keys1 can stand out, and some musical styles like rock or jazz thrive on complex minor scales and harmonic wizardry. Minor chord progressions generally contain richer harmonic possibilities than the typical major progressions. Minor key songs frequently modulate to major and back to minor. Sometimes the same chord can appear as major and minor in the very same song! But this heady harmonic mix is nothing to be afraid of. By the end of this article, you’ll not only understand how minor chords are made, but you’ll know some common minor chord progressions, how to write them, and how to use them in your own music. With enough listening practice, you’ll be able to recognize minor chord progressions in songs almost instantly! Table of Contents: 1. A Tale of Two Tonalities 2. Major or Minor? 3. Chords in Minor Scales 4. The Top 3 Chords in Minor Progressions 5. Exercises in Minor 6. Writing Your Own Minor Chord Progressions 7. Your Minor Journey 1 https://www.musical-u.com/learn/the-ultimate-guide-to-minor-keys A Tale of Two Tonalities Western music is dominated by two tonalities: major and minor. -

Models of Octatonic and Whole-Tone Interaction: George Crumb and His Predecessors

Models of Octatonic and Whole-Tone Interaction: George Crumb and His Predecessors Richard Bass Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 38, No. 2. (Autumn, 1994), pp. 155-186. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-2909%28199423%2938%3A2%3C155%3AMOOAWI%3E2.0.CO%3B2-X Journal of Music Theory is currently published by Yale University Department of Music. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/yudm.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Mon Jul 30 09:19:06 2007 MODELS OF OCTATONIC AND WHOLE-TONE INTERACTION: GEORGE CRUMB AND HIS PREDECESSORS Richard Bass A bifurcated view of pitch structure in early twentieth-century music has become more explicit in recent analytic writings. -

AP Music Theory Course Description Audio Files ”

MusIc Theory Course Description e ffective Fall 2 0 1 2 AP Course Descriptions are updated regularly. Please visit AP Central® (apcentral.collegeboard.org) to determine whether a more recent Course Description PDF is available. The College Board The College Board is a mission-driven not-for-profit organization that connects students to college success and opportunity. Founded in 1900, the College Board was created to expand access to higher education. Today, the membership association is made up of more than 5,900 of the world’s leading educational institutions and is dedicated to promoting excellence and equity in education. Each year, the College Board helps more than seven million students prepare for a successful transition to college through programs and services in college readiness and college success — including the SAT® and the Advanced Placement Program®. The organization also serves the education community through research and advocacy on behalf of students, educators, and schools. For further information, visit www.collegeboard.org. AP Equity and Access Policy The College Board strongly encourages educators to make equitable access a guiding principle for their AP programs by giving all willing and academically prepared students the opportunity to participate in AP. We encourage the elimination of barriers that restrict access to AP for students from ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic groups that have been traditionally underserved. Schools should make every effort to ensure their AP classes reflect the diversity of their student population. The College Board also believes that all students should have access to academically challenging course work before they enroll in AP classes, which can prepare them for AP success. -

Discover Seventh Chords

Seventh Chords Stack of Thirds - Begin with a major or natural minor scale (use raised leading tone for chords based on ^5 and ^7) - Build a four note stack of thirds on each note within the given key - Identify the characteristic intervals of each of the seventh chords w w w w w w w w % w w w w w w w Mw/M7 mw/m7 m/m7 M/M7 M/m7 m/m7 d/m7 w w w w w w % w w w w #w w #w mw/m7 d/wm7 Mw/M7 m/m7 M/m7 M/M7 d/d7 Seventh Chord Quality - Five common seventh chord types in diatonic music: * Major: Major Triad - Major 7th (M3 - m3 - M3) * Dominant: Major Triad - minor 7th (M3 - m3 - m3) * Minor: minor triad - minor 7th (m3 - M3 - m3) * Half-Diminished: diminished triad - minor 3rd (m3 - m3 - M3) * Diminished: diminished triad - diminished 7th (m3 - m3 - m3) - In the Major Scale (all major scales!) * Major 7th on scale degrees 1 & 4 * Minor 7th on scale degrees 2, 3, 6 * Dominant 7th on scale degree 5 * Half-Diminished 7th on scale degree 7 - In the Minor Scale (all minor scales!) with a raised leading tone for chords on ^5 and ^7 * Major 7th on scale degrees 3 & 6 * Minor 7th on scale degrees 1 & 4 * Dominant 7th on scale degree 5 * Half-Diminished 7th on scale degree 2 * Diminished 7th on scale degree 7 Using Roman Numerals for Triads - Roman Numeral labels allow us to identify any seventh chord within a given key. -

Music in Theory and Practice

CHAPTER 4 Chords Harmony Primary Triads Roman Numerals TOPICS Chord Triad Position Simple Position Triad Root Position Third Inversion Tertian First Inversion Realization Root Second Inversion Macro Analysis Major Triad Seventh Chords Circle Progression Minor Triad Organum Leading-Tone Progression Diminished Triad Figured Bass Lead Sheet or Fake Sheet Augmented Triad IMPORTANT In the previous chapter, pairs of pitches were assigned specifi c names for identifi cation CONCEPTS purposes. The phenomenon of tones sounding simultaneously frequently includes group- ings of three, four, or more pitches. As with intervals, identifi cation names are assigned to larger tone groupings with specifi c symbols. Harmony is the musical result of tones sounding together. Whereas melody implies the Harmony linear or horizontal aspect of music, harmony refers to the vertical dimension of music. A chord is a harmonic unit with at least three different tones sounding simultaneously. Chord The term includes all possible such sonorities. Figure 4.1 #w w w w w bw & w w w bww w ww w w w w w w w‹ Strictly speaking, a triad is any three-tone chord. However, since western European music Triad of the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries is tertian (chords containing a super- position of harmonic thirds), the term has come to be limited to a three-note chord built in superposed thirds. The term root refers to the note on which a triad is built. “C major triad” refers to a major Triad Root triad whose root is C. The root is the pitch from which a triad is generated. 73 3711_ben01877_Ch04pp73-94.indd 73 4/10/08 3:58:19 PM Four types of triads are in common use. -

Viewed by Most to Be the Act of Composing Music As It Is Being

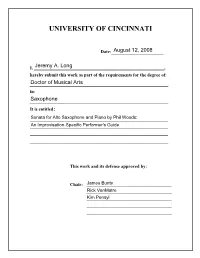

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods: An Improvisation-Specific Performer’s Guide A doctoral document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music By JEREMY LONG August, 2008 B.M., University of Kentucky, 1999 M.M., University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music, 2002 Committee Chair: Mr. James Bunte Copyright © 2008 by Jeremy Long All rights reserved ABSTRACT Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods combines Western classical and jazz traditions, including improvisation. A crossover work in this style creates unique challenges for the performer because it requires the person to have experience in both performance practices. The research on musical works in this style is limited. Furthermore, the research on the sections of improvisation found in this sonata is limited to general performance considerations. In my own study of this work, and due to the performance problems commonly associated with the improvisation sections, I found that there is a need for a more detailed analysis focusing on how to practice, develop, and perform the improvised solos in this sonata. This document, therefore, is a performer’s guide to the sections of improvisation found in the 1997 revised edition of Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods. -

02-11-Nonchordtones.Pdf

LearnMusicTheory.net 2.11 Nonchord Tones Nonchord tones = notes that aren't part of the chord. Nonchord tones always embellish/decorate chord tones. Keep in mind that many authors use the term "consonance" for a chord tone, and "dissonance" for a nonchord tone. suspension (S) = "delayed step down" passing tone (PT) neighbor tone (NT) 1. Starts as chord tone, then becomes... PTs are approached and NTs are approached and 2. Nonchord tone metrically accented, left by step in the left by step in different 3. ...then resolves down by step same direction. directions. Common types: 7-6, 4-3, 9-8, 2-3 Preparation Suspension Resolution C:IV6 I escape tone (esc.) retardation (R) -"step-leap" 1. Starts as chord tone, then becomes... appoggiatura (app.) -"leap-step" -to escape, you "step to window, 2. Nonchord tone metrically accented leap out" 3. ...then resolves up by step -may be metrically accented or unaccented -may be metrically accented or unaccented "DELAYED STEP UP" -sometimes called "incomplete neighbor tone" -also sometimes called "incomplete Preparation Retardation Resolution neighbor tone" vii°6 I anticipation (ant.) cambiata (c) -- LESS COMMON -approached by leap or step -also called "changing tone" from either direction -connect 2 consonances a 3rd apart -unaccented (i.e. C-A in this example) neighbor group (n gr.) -must be a chord tone in the -only the 2nd note of the pattern is -upper and lower neighbor together next harmony a dissonance -can also be lower neighbor -may or may not be tied into -specific pattern shown below followed by upper neighbor the resolution note -common in 15th and 16th centuries vii°6 I pedal point or pedal tone (bottom C in left hand) from Bach, WTC, Fugue I in C, m. -

Brain Tumors : Practical Guide to Diagnosis and Treatment

Brain Tumors DK616x_C000a.indd 1 09/01/2006 8:49:40 AM NEUROLOGICAL DISEASE AND THERAPY Advisory Board Gordon H. Baltuch, M.D., Ph.D. Department of Neurosurgery University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.A. Cheryl Bushnell, M.D., M.H.S. Duke Center for Cerebrovascular Disease Department of Medicine, Division of Neurology Duke University Medical Center Durham, North Carolina, U.S.A. Louis R. Caplan, M.D. Professor of Neurology Harvard University School of Medicine Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.A. Mark A. Stacy, M.D. Movement Disorders Center Duke University Medical Center Durham, North Carolina, U.S.A. Mark H. Tuszynski, M.D., Ph.D. Professor of Neurosciences Director, Center for Neural Repair University of California—San Diego La Jolla, California, U.S.A. DK616x_C000a.indd 2 09/01/2006 8:49:43 AM 1. Handbook of Parkinson’s Disease, edited by William C. Koller 2. Medical Therapy of Acute Stroke, edited by Mark Fisher 3. Familial Alzheimer’s Disease: Molecular Genetics and Clinical Perspectives, edited by Gary D. Miner, Ralph W. Richter, John P. Blass, Jimmie L. Valentine, and Linda A. Winters-Miner 4. Alzheimer’s Disease: Treatment and Long-Term Management, edited by Jeffrey L. Cummings and Bruce L. Miller 5. Therapy of Parkinson’s Disease, edited by William C. Koller and George Paulson 6. Handbook of Sleep Disorders, edited by Michael J. Thorpy 7. Epilepsy and Sudden Death, edited by Claire M. Lathers and Paul L. Schraeder 8. Handbook of Multiple Sclerosis, edited by Stuart D. Cook 9. Memory Disorders: Research and Clinical Practice, edited by Takehiko Yanagihara and Ronald C. -

Generalized Interval System and Its Applications

Generalized Interval System and Its Applications Minseon Song May 17, 2014 Abstract Transformational theory is a modern branch of music theory developed by David Lewin. This theory focuses on the transformation of musical objects rather than the objects them- selves to find meaningful patterns in both tonal and atonal music. A generalized interval system is an integral part of transformational theory. It takes the concept of an interval, most commonly used with pitches, and through the application of group theory, generalizes beyond pitches. In this paper we examine generalized interval systems, beginning with the definition, then exploring the ways they can be transformed, and finally explaining com- monly used musical transformation techniques with ideas from group theory. We then apply the the tools given to both tonal and atonal music. A basic understanding of group theory and post tonal music theory will be useful in fully understanding this paper. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 A Crash Course in Music Theory 2 3 Introduction to the Generalized Interval System 8 4 Transforming GISs 11 5 Developmental Techniques in GIS 13 5.1 Transpositions . 14 5.2 Interval Preserving Functions . 16 5.3 Inversion Functions . 18 5.4 Interval Reversing Functions . 23 6 Rhythmic GIS 24 7 Application of GIS 28 7.1 Analysis of Atonal Music . 28 7.1.1 Luigi Dallapiccola: Quaderno Musicale di Annalibera, No. 3 . 29 7.1.2 Karlheinz Stockhausen: Kreuzspiel, Part 1 . 34 7.2 Analysis of Tonal Music: Der Spiegel Duet . 38 8 Conclusion 41 A Just Intonation 44 1 1 Introduction David Lewin(1933 - 2003) is an American music theorist.