A Practical Guide to Using Digital Games As an Experiment Stimulus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

School of Game Development Program Brochure

School of Game Development STEM certified school academyart.edu SCHOOL OF GAME DEVELOPMENT Contents Program Overview .................................................. 5 What We Teach ......................................................... 7 The School of Game Development Difference ....... 9 Faculty .................................................................... 11 Degree Options ...................................................... 13 Our Facilities ........................................................... 15 Student & Alumni Testimonials ............................ 17 Partnerships .......................................................... 19 Career Paths .......................................................... 21 Additional Learning Experiences ......................... 23 Awards and Accolades ......................................... 25 Online Education .................................................. 27 Academy Life ........................................................ 29 San Francisco ........................................................ 31 Athletics ................................................................ 33 Apply Today .......................................................... 35 3 SCHOOL OF GAME DEVELOPMENT Program Overview We offer two degree tracks—Game Development and Game Programming. Pursue your love for both the art and science of games at the School of Game Development. OUR MISSION WHAT SETS US APART Don’t let the word “game” fool you. The gaming • Learn both the art, (Game Development) and -

The Fate of New Legislation Curbing Minors' Access to Violent and Sexually Explicit Video Games

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 26 Number 2 Article 2 1-1-2006 If You Fail, Try, Try Again: The Fate of New Legislation Curbing Minors' Access to Violent and Sexually Explicit Video Games Russell Morse Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Russell Morse, If You Fail, Try, Try Again: The Fate of New Legislation Curbing Minors' Access to Violent and Sexually Explicit Video Games, 26 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 171 (2006). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol26/iss2/2 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IF YOU FAIL, TRY, TRY AGAIN: THE FATE OF NEW LEGISLATION CURBING MINORS' ACCESS TO VIOLENT AND SEXUALLY EXPLICIT VIDEO GAMES I. INTRODUCTION The new "Hot Coffee" modification discovered within the hugely popular, but exceedingly violent, video game Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas ("GTA: San Andreas") has re-ignited the debate whether such video games have adverse effects on children.' "Hot Coffee" refers to the modification which, when installed, brings the player to a secret level prompting that player to have the game's hero engage in sexually explicit acts.2 Some parents and psychologists fear that exposure to violent and sexually explicit video games, like the "Hot Coffee"-enabled version of GTA: San Andreas, have a deleterious effect on children, leading to heightened aggression and anti-social behavior.3 The makers of these games deny these claims and argue that the ratings system in existence for video games adequately protects children.4 Politicians across the country have jumped into the fray by proposing 1. -

1 Before the U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE, LIBRARY of CONGRESS

Before the U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS In the Matter of Exemption to Prohibition on Circumvention of Copyright Protection Systems for Access Control Technologies Docket No. 2014-07 Reply Comments of the Electronic Frontier Foundation 1. Commenter Information Mitchell Stoltz Kendra Albert Corynne McSherry (203) 424-0382 Kit Walsh [email protected] Electronic Frontier Foundation 815 Eddy St San Francisco, CA 94109 (415) 436-9333 [email protected] The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) is a member-supported, nonprofit public interest organization devoted to maintaining the traditional balance that copyright law strikes between the interests of copyright owners and the interests of the public. Founded in 1990, EFF represents over 25,000 dues-paying members, including consumers, hobbyists, artists, writers, computer programmers, entrepreneurs, students, teachers, and researchers, who are united in their reliance on a balanced copyright system that ensures adequate incentives for creative work while facilitating innovation and broad access to information in the digital age. In filing these reply comments, EFF represents the interests of gaming communities, archivists, and researchers who seek to preserve the functionality of video games abandoned by their manufacturers. 2. Proposed Class Addressed Proposed Class 23: Abandoned Software—video games requiring server communication Literary works in the form of computer programs, where circumvention is undertaken for the purpose of restoring access to single-player or multiplayer video gaming on consoles, personal computers or personal handheld gaming devices when the developer and its agents have ceased to support such gaming. We propose an exemption to 17 U.S.C. § 1201(a)(1) for users who wish to modify lawfully acquired copies of computer programs for the purpose of continuing to play videogames that are no longer supported by the developer, and that require communication with a server. -

Challenges for Game Designers Brenda Brathwaite And

CHALLENGES FOR GAME DESIGNERS BRENDA BRATHWAITE AND IAN SCHREIBER Charles River Media A part of Course Technology, Cengage Learning Australia, Brazil, Japan, Korea, Mexico, Singapore, Spain, United Kingdom, United States Challenges for Game Designers © 2009 Course Technology, a part of Cengage Learning. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright Brenda Brathwaite and Ian Schreiber herein may be reproduced, transmitted, stored, or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including but not limited to photocopying, recording, scanning, digitizing, taping, Web distribution, Publisher and General Manager, information networks, or information storage and retrieval systems, except Course Technology PTR: as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Stacy L. Hiquet Act, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Associate Director of Marketing: For product information and technology assistance, contact us at Sarah Panella Cengage Learning Customer & Sales Support, 1-800-354-9706 For permission to use material from this text or product, Content Project Manager: submit all requests online at cengage.com/permissions Jessica McNavich Further permissions questions can be emailed to [email protected] Marketing Manager: Jordan Casey All trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Acquisitions Editor: Heather Hurley Library of Congress Control Number: 2008929225 Project and Copy Editor: Marta Justak ISBN-13: 978-1-58450-580-8 ISBN-10: 1-58450-580-X CRM Editorial Services Coordinator: Jen Blaney eISBN-10: 1-58450-623-7 Course Technology Interior Layout: Jill Flores 25 Thomson Place Boston, MA 02210 USA Cover Designer: Tyler Creative Services Cengage Learning is a leading provider of customized learning solutions with office locations around the globe, including Singapore, the United Kingdom, Indexer: Sharon Hilgenberg Australia, Mexico, Brazil, and Japan. -

Advertising: Video Games

Advertising: Video Games Recent Articles on Ads and Video games October 2008 Advertising Strategists Target Video Games April 21, 2006 10:33AM Visa isn’t the only brand getting into the virtual action. In-game advertising is expected to double to nearly $350 million by next year, and hit well over $700 million by 2010, according to a report released this week by research firm the Yankee Group. Advertisers are getting into the game — the video game. Increasingly, big-name marketers are turning to game developers to woo consumers more interested in the game controller than the remote control. “The fact is you aren’t able to reach consumers the same way you could 20 years ago, 10 years ago or maybe even five years ago,” said Jon Raj, vice president of advertising and emerging media platform for Visa USA. Visa ingrained itself into Ubisoft’s PC title “CSI 3” by making the credit card company’s identity theft protection part of the game’s plot. “We didn’t just want to throw our billboard or put our Visa logo out there,” Raj said. Visa isn’t the only brand getting into the virtual action. In-game advertising is expected to double to nearly $350 million by next year, and hit well over $700 million by 2010, according to a report released this week by research firm the Yankee Group. Bay State game creators are already reporting an uptick in interest from marketers wanting to roll real-life ads into fantasy worlds. “I’ve seen increased interest here and throughout the industry,” said Joe Brisbois, vice president of business development for Cambridge-based Harmonix Music Systems. -

000NAG E3 Supplement 2004

E3 2004 SUPPLEMENT It’s an undeniable fact - we love gaming. Why else would we spend 23 hours in the air, endure the rigours of the US Customs checks, not once, not twice, but three times in the space of 15 min- utes by three different officials, only to miss a connecting flight and in the process, miss our first scheduled press conference, arrive in LA tired and harassed and spend the next five days in a whirlwind of meetings, conferences, behind closed door viewings and getting our hands on some of the mind-blowing titles that will be released over the next year or so? [You get paid? Ed] We did it all for you, the reader, so that we could come back home, contents experience three days of severe jet lag, stumble into the midst of another NAG deadline and slave away for a week putting this sup- plement together. So please, when you flip through the pages of this supplement gasping at the unbelievable screenshots, try and read at least one line on every page, allowing us the indulgence of E3 Conferences 10 thinking that our efforts actually brought joy to a gamers life. More exciting than wandering around For those of you new to this whole E3 fanfare, welcome. It's our fifth Downtown L.A. in the middle of the night. stint at the world's largest electronic entertainment expo, and while we like to think of ourselves as E3 gaming veterans, we always State of the Industry 12 come away with a renewed sense of excitement at where the indus- Take a look at the facts and figures of the gam- ing industry. -

Eminem the Complete Guide

Eminem The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Wed, 01 Feb 2012 13:41:34 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Eminem 1 Eminem discography 28 Eminem production discography 57 List of awards and nominations received by Eminem 70 Studio albums 87 Infinite 87 The Slim Shady LP 89 The Marshall Mathers LP 94 The Eminem Show 107 Encore 118 Relapse 127 Recovery 145 Compilation albums 162 Music from and Inspired by the Motion Picture 8 Mile 162 Curtain Call: The Hits 167 Eminem Presents: The Re-Up 174 Miscellaneous releases 180 The Slim Shady EP 180 Straight from the Lab 182 The Singles 184 Hell: The Sequel 188 Singles 197 "Just Don't Give a Fuck" 197 "My Name Is" 199 "Guilty Conscience" 203 "Nuttin' to Do" 207 "The Real Slim Shady" 209 "The Way I Am" 217 "Stan" 221 "Without Me" 228 "Cleanin' Out My Closet" 234 "Lose Yourself" 239 "Superman" 248 "Sing for the Moment" 250 "Business" 253 "Just Lose It" 256 "Encore" 261 "Like Toy Soldiers" 264 "Mockingbird" 268 "Ass Like That" 271 "When I'm Gone" 273 "Shake That" 277 "You Don't Know" 280 "Crack a Bottle" 283 "We Made You" 288 "3 a.m." 293 "Old Time's Sake" 297 "Beautiful" 299 "Hell Breaks Loose" 304 "Elevator" 306 "Not Afraid" 308 "Love the Way You Lie" 324 "No Love" 348 "Fast Lane" 356 "Lighters" 361 Collaborative songs 371 "Dead Wrong" 371 "Forgot About Dre" 373 "Renegade" 376 "One Day at a Time (Em's Version)" 377 "Welcome 2 Detroit" 379 "Smack That" 381 "Touchdown" 386 "Forever" 388 "Drop the World" -

1/16" Safety Zone 7.1875"

Electronic Template: Manual Cover, Version 4.0 (DOC-000563 Rev 0) File name: TP_PS2ManualCover.eps For illustration purpose only. Use electronic template for specifications. Do not alter, change or move items in template unless specifically noted to do so. NOTE: Turn off “Notes” and “Measurements” layers when printing. Rev 9/03 1/8" BLEED ZONE 1/16" SAFETY ZONE 7.1875" COMING SPRING 2006 www.HITMANBLOODMONEY.com © 2006 IO Interactive A/S. Developed by IO Interactive. Published by Eidos. Hitman Blood Money , Eidos and the Eidos logo are trademarks of the Eidos Group of Companies. Io and the IO logo are trademarks of IO Interactive A/s. All rights reserved. P25TLSUS03 4.5" 4.5" 9.0" ttl ps2 final gs 11/7/05 8:05 PM Page ii CONTENTS ® WARNING: READ BEFORE USING YOUR PLAYSTATION 2 GETTING STARTED ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ 2 COMPUTER ENTERTAINMENT SYSTEM. CONTROLLER ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ 3 A very small percentage of individuals may experience epileptic seizures when exposed to certain light patterns or flashing lights. PULL THE TRIGGER ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ 4 visit Exposure to certain patterns or backgrounds on a television screen DEFAULT CONTROLS ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ 5 or while playing video games, including games played on the EIDOS: PlayStation 2 console, may induce an epileptic seizure in these GETTING INTO THE GAME ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ 6 individuals. Certain conditions may induce previously undetected Creating a Profile ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ 6 www. epileptic symptoms even in persons who have no history of prior Main Menu ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ 6 eidos. seizures or epilepsy. If you, or anyone in your family, has an epileptic Saving Game Data ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ 6 com condition, consult your physician prior to playing. -

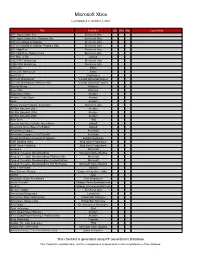

Microsoft Xbox

Microsoft Xbox Last Updated on October 2, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 007: Agent Under Fire Electronic Arts 007: Agent Under Fire: Platinum Hits Electronic Arts 007: Everything or Nothing Electronic Arts 007: Everything or Nothing: Platinum Hits Electronic Arts 007: NightFire Electronic Arts 007: NightFire: Platinum Hits Electronic Arts 187 Ride or Die Ubisoft 2002 FIFA World Cup Electronic Arts 2006 FIFA World Cup Electronic Arts 25 to Life Eidos 25 to Life: Bonus CD Eidos 4x4 EVO 2 GodGames 50 Cent: Bulletproof Vivendi Universal Games 50 Cent: Bulletproof: Platinum Hits Vivendi Universal Games Advent Rising Majesco Aeon Flux Majesco Aggressive Inline Acclaim Airforce Delta Storm Konami Alias Acclaim Aliens Versus Predator: Extinction Electronic Arts All-Star Baseball 2003 Acclaim All-Star Baseball 2004 Acclaim All-Star Baseball 2005 Acclaim Alter Echo THQ America's Army: Rise of a Soldier: Special Edition Ubisoft America's Army: Rise of a Soldier Ubisoft American Chopper Activision American Chopper 2: Full Throttle Activision American McGee Presents Scrapland Enlight Interactive AMF Bowling 2004 Mud Duck Productions AMF Xtreme Bowling Mud Duck Productions Amped 2 Microsoft Amped: Freestyle Snowboarding Microsoft Game Studios Amped: Freestyle Snowboarding: Platinum Hits Microsoft Amped: Freestyle Snowboarding: Limited Edition Microsoft Amped: Freestyle Snowboarding: Not for Resale Microsoft Game Studios AND 1 Streetball UbiSoft Antz Extreme Racing Empire Interactive / Light... APEX Atari Aquaman: Battle For Atlantis TDK -

Rated M for Mature: Violent Video Game Legislation and the Obscenity Standard

Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development Volume 24 Issue 4 Volume 24, Summer 2010, Issue 4 Article 3 Rated M for Mature: Violent Video Game Legislation and the Obscenity Standard Jennifer Chang Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcred This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES RATED M FOR MATURE: VIOLENT VIDEO GAME LEGISLATION AND THE OBSCENITY STANDARD BY JENNIFER CHANG* It's your typical dark and stormy night at the insane asylum. You wake up in your cell to find that a freak electrical problem has left the door wide open. A sinister voice beckons you to follow it and advises you to stay in the shadows so as not to be seen by the other cell dwellers. You sneak past the first two but the third catches a glimpse of you and goes wild, throwing feces in your general direction. You're told to grab the syringe from the floor as it will be a useful weapon. Up ahead, a nurse facing the other way stands between you and a door to the next room. You neither know who he is, nor does he know that you're standing there lurking behind him. The voice commands you to kill, and you protest. Suddenly, your heart races, your palms get sweaty, and your vision blurs. -

PC GAMES and DRAGONS! the PC Gaming Authority

INSIDE! IN THE MAG: CGW'S LEGENDARY ANNUAL HANDS-ON REPORT DUNGEONS & DRAGONS 101 Free ONLINE: STORMREACH WE SAW DUNGEONS— PLAY THE DEMOS! PC GAMES AND DRAGONS! The PC Gaming Authority FOR OVER 20 YEARS 101CGW'S LEGENDARY ANNUALFREEISSUE 260 PC GAMES SHOOTERS PUZZLES PLATFORMERS AND MORE! WE TELL YOU WHERE TO FIND 'EM ALL! FIRST LOOK CRYSIS MORE EXPLOSIVE ACTION FROM THE MAKERS OF FAR CRY! SPECIAL REPORT: MOD SUMMIT FIRST LOOK! THE WORLD’S LEADING GOTHIC 3 YAY! THE SINGLE- MODMAKERS DISCUSS PLAYER RPG THE FUTURE OF RETURNS! PAGE 18 PC GAMING > ON THE DISC REVIEWED TM STAR WARS THE YEAR’S FIRST 5-STAR EMPIRE AT WAR DEMO! ISSUE 260 PLUS: HOT HALF-LIFE 2 AND DOOM 3 GAME IS ONE MAPS AND MODS! YOU’VE NEVER BIG TRAILERS: SPLINTER CELL HEARD OF 21 Display Until March DOUBLE AGENT, THE GODFATHER! SEE PAGE 87 $8.99 U.S. $9.99 Canada > MARCH 2006 CGW.1UP.COM THE FATE OF THE ENTIRE ARE YOU THE FLEETS Do you quickly build a fleet of TIE fighters and swarm the enemy before they gain strength? Or take time and build a more THE ELEMENTS powerful fleet of Star Destroyers? Do you wait until after the ice storm and lose the element of surprise? Or do you take advantage of low visibility and attack when they least expect it? THE ARMIES Do you crush bases under the feet of AT-ATs and risk losing a few? Or do you call down ships from space and bomb them back to the Stone Age? Will you repeat Star Wars® history or change it forever? Play Star Wars : Empire at War and test your strategic mettle in an epic fight to control the entire Star Wars galaxy. -

Games Made in Texas (1981 – 2021) Page 1 of 17

Games Made in Texas (1981 – 2021) Page 1 of 17 Release Date Name Developer Platform Location 2021-01-02 Yes! Our Kids Can Video Game - Third Grade Yes! Our Kids Can San Antonio Magnin & Associates (Magnin iOS, Android, Apple TV, 2020-09-30 Wheelchair Mobility Experience Games) Mac, PC, Xbox One Dallas; Richardson 2020-09-17 Shark Tank Tycoon Game Circus, LLC Addison Stadia currently; Steam / 2020-07-13 Orcs Must Die! 3 Robot Entertainment Xbox / PlayStation in 2021 Plano 2019-12-31 Path of the Warrior (VR) Twisted Pixel Games Austin 2019-10-29 Readyset Heroes Robot Entertainment, Inc. Mobile Plano Xbox One, Playstation 4, 2019-09-13 Borderlands 3 Gearbox Software PC Frisco 2019-08-13 Vicious Circle Rooster Teeth Austin 2019-08-01 Stranger Things 3 BonusXP Nintendo Switch Allen 2019-07-11 Defector Twisted Pixel Games Oculus Rift Austin Android, PlayStation 4, Nintendo Switch, Xbox One, iOS, Microsoft 2019-06-28 Fortnight Phase 2 Armature Studio Windows, Mac, Mobile Austin Microsoft Windows & 2019-06-21 Dreadnought 2 Six Foot Games PlayStation 4 Houston 2019-05-31 Sports Scramble Armature Studio Oculus Quest Austin 2019-05-02 Duck Game Armature Studio Nintendo Switch Austin 2019-03-15 Zombie Boss Boss Fight Entertainment, Inc Allen; McKinney Windows (Steam); Oculus 2018-12-31 Baby Hands Chicken Waffle Rift Austin 2018-12-31 Baby Hands Jr. Chicken Waffle iOS; Android Austin 2018-12-19 Arte Lumiere Triseum Microsoft Windows Bryan 2018-11-15 Dreadnought 1: Command The Colossal Six Foot, LLC Houston 2018-10-10 World Armature Studio LLC Austin 2018-10-05 Donkey Kong Country: Tropical Freeze Retro Studios Austin Windows (Steam); HTC 2018-08-27 Torn Aspyr Media Inc.